Mk 15:30

When making the Stations of the Cross, particularly in stations 3, 7, 9, where Jesus falls, I meditate on this truth most fully. Why not stay down? The release of not carrying the full weight must be welcome, but the fall hurt, too. The Roman soldiers will beat Him to death where He lay if He does not move. He still has His most important work to do, as do we. Jesus, help me rise as You did, when I fall from the exhaustion, horror, and great burden of my own crosses. I have work to do, Lord. Be my help, my strength, and my salvation.

The Jesuit priest St. Noel Chabanel, SJ was one of the North American Martyrs; he worked among the Huron Indians with St. Charles Garnier. Missionaries often become very sympathetic toward those to whom they minister, but this was not the case for Fr. Noel; he felt a strong repugnance for the Indians and their customs. This, along with difficulty in learning their language and similar challenges, caused him a lasting sense of sadness and spiritual suffocation. How did he respond? By making a solemn vow never to give up or to leave his assignment — a vow that he kept until the day of his martyrdom.

-by PETER AMBROSIE

A CALL TO COURAGE

“I am going where obedience calls me, but whether I stay there or receive permission from my superior to return to the mission where I belong, I must serve God faithfully until death.” These, perhaps his last recorded words, Rev. Noel Chabanel, SJ spoke on the very day of his death, Dec. 8, 1649 to the Fathers in charge of St. Matthias mission among the Petuns. They give us the measure of this unique Martyr and Saint. St Mere Marie de l’Incarnation in a letter to her son dated Aug.30, 1650 said of him, “Whatever may be, he died in the act of obedience.”

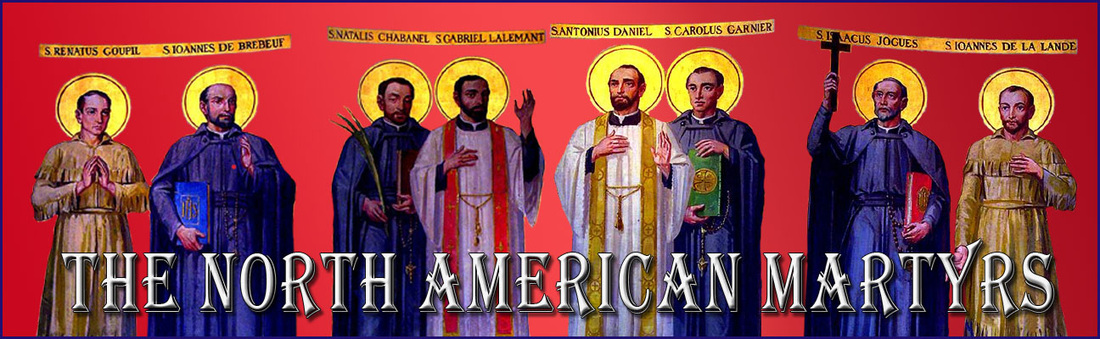

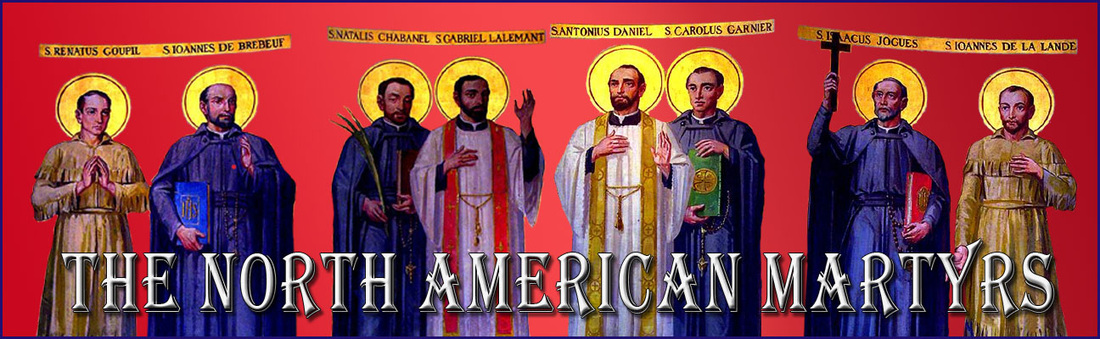

What kind of man was Noel Chabanel? From the viewpoint of the length, intensity and success of their missionary activities the eight North American Martyrs fall into two groups: the “big four” and the “little four.” Brebeuf, Daniel, Garnier and Jogues belong to the first class; Lalemant, Goupil, de la Lande and Noel Chabanel, to the second. The “little four” suffer by contrast with the herculean labors of the “big four.” But all of them equally shed their blood in witness to Christ and His message.

EARLY YEARS

Noel Chabanel was the youngest of the priests and the last of the band of eight to suffer martyrdom in the new world. His birthplace in south-eastern France, the village of Saugues about a hundred miles northwest of the port of Marseilles, nestled in hill country which was the source of four rivers, the Loire, Seine, Garonne and Rhone. Here on the banks of the Lozere, a tributary of the Loire, Chabanel was born on Feb. 2, 1613, the feast of the Purification of Our Lady. His father, a notary, and his mother sprung from merchant stock, raised their four children, Pierre, Claude, Antoinette and Noel, the youngest, in comfort, yet in the firmness of the traditional Catholic upbringing of early 17th century France.

Though the details of his boyhood are somewhat scanty, we know that Noel was first educated in the basic humanities in the Chapter school in Saugues and then as a teenager in higher studies at an unknown college. His brother Pierre entered the Society of Jesus in 1623 and Noel, just past seventeen years old, entered the Jesuit novitiate in Toulouse on Feb. 8, 1630. After a two years novitiate and his first vows he taught rhetoric quite successfully in the college of that city from 1632-1639.

From 1639 to 1641 he did his studies in theology there, followed by his Tertianship, a third probationary year, still in Toulouse, 1641-1642. In 1641 he was ordained a priest. His years of training ended in a classroom teaching rhetoric again, this time at the college of Rodez The Jesuit catalogue for the Province of Toulouse leaves this pointed portrait of Chabanel: “Serious by nature – energetic – great stability -better than average intelligence.”

BIRTH OF A MISSIONARY

During his twelve years as a Jesuit the young Society of Jesus knew its golden age in France, multiplying into five Provinces or territorial divisions between the years 1545 and 1616. Jesuit foreign missionary activity, too, spread east, west and south. From the famous Jesuit Rela-tions Noel learned of the heroic work of his fellow Jesuits in New France. In the seventeenth century sophisticated France was thrilled with the tales graphically written each year by the Jesuits in New France. These were the Jesuit Relations – one of the world’s most famous records of adventure, history and heroic sanctity, unique be-cause they were history written on the spot in the hour of its making.

Especially during his Tertianship the tiny flame of his ambition to become a missionary fanned into a fierce desire. In the words of his chief chronicler, Paul Ragueneau, “God gave him a strong vocation for this country.” Twice he wrote to the General of the Society of Jesus in Rome, Mutius Vitelleschi. The first time requesting that his studies be curtailed and that he be sent immediately to answer the urgent call for missionaries in New France. The reply of the General on November 15, 1642, though negative, left the door open. Finally on April 4, 1643 his obedient patience was rewarded when a reply from the General to his second letter allowed him to leave for New France.

On May 8,1643 Noel’s dream became a reality. As he stood aboard-ship in the port of Dieppe, this young priest, thirty years old, looked west across the Atlantic with its bright promise of adventure for Christ. Little did he suspect how strange, how mysterious, how demanding the adventure in New France was to be for a sensitive young man raised and schooled in the comparative comfort, shelter and luxury of old France.

With Noel travelled two Jesuits, Gabriel Druillet and Leonard Garreau, a native of Limoges of the Province of Aquitaine. Could Noel suspect that Father Garreau would be the last Jesuit he would see and confide in, on the eve of his death?

ARRIVAL IN QUEBEC

The perilous crossing of the Atlantic in the early 17th century with its many hazards has often been described in the Jesuit Relations. This was Noel’s special introduction to the new world and a presage of what was in store for him. After a three months’ voyage they landed in the settlement of Quebec on August 15. Ironically, the Relation of that year records that his confreres in Quebec were overjoyed at the arrival of “three worthy workers, Religious of our Society, and very apt for the language.” The life of Chabanel was to prove how unprophetic these words were to be for him! For, of the five Jesuit Martyrs killed in Canada, Noel was the only one who had no flair for the native languages.

INSECURITY OF THE FRENCH SETTLEMENTS

The picture in New France was anything but bright the past year. 1642 was a year of great crisis for the missionaries in Huronia. The Huron mission had been cut off from Quebec by the Iroquois blockade. No flotilla of Huron canoes had come down to Quebec for the yearly trade. By the same token no provisions had made their way back to the isolated mission in Huronia. Finally in the summer of 1642 Isaac Jogues, a veteran of six years in the Huron missions, was picked to break through the blockade for desperately needed supplies. Miraculously he made the journey to Quebec after thirty-five days canoeing. On his return trip to Sainte-Marie Jogues and Rene’ Goupil were am-bushed and taken captive into Iroquois territory, where Goupil, sur-geon and saint, suffered martyrdom on September 29,1642, the first of the band of eight to die a martyr. Even the inhabitants of Quebec, Three Rivers and the recently founded settlement of Ville Marie (Montreal) did not escape the cruel and daring raids of the prowling Iroquois. It was during this period of fear and uncertainty that Noel landed in Quebec. Although warmly welcomed by his Jesuit brothers -and this compensated somewhat for the crude conditions he found – he could feel the atmosphere of danger, fear and insecurity.

A highlight of Noel’s winter stay in Quebec was meeting the senior veteran missionary, Rev. Jean de Brebeuf,SJ who had left Huronia in 1641 suffering from a broken left clavicle sustained while on a mission among the Neutrals. In Quebec during his recuperation period Brebeuf served as procurator or supplier for the Huron mission. Because of the hazard of journeying that fall of 1643 to the Huron mission, Noel Chabanel had to stay in Quebec that winter getting his first initiation of missionary work in and around the settlement. Like all newly arrived blackrobes, his ignorance of the difficult Indian languages – so different from his polished French – would curtail his initial apostolate among the native people. So Father Noel would do chaplain duty at the Ursuline Convent and work with the colonists and soldiers of the little settlement.

HURONIA BOUND -1644

When the ice went out of the St. Lawrence in the spring of 1644, Father Bressani made a desperate attempt to carry aid to the isolated Fathers in distant Huronia. He and his party were ambushed and taken captive by the lurking Iroquois. In late spring a few christian Hurons managed to arrive in Quebec from Huronia with word of the dire needs of the blackrobes there. On their return trip after trading they too were seized by the enemy. Finally, Governor Montmagny decided to send an armed escort of a score of French soldiers to Sainte-Marie, the black-robe missionary centre on the Wye River in Huronia. So in midsummer of 1644 Fathers Brebeuf, Chabanel and Garreau left Quebec in an attempt to reach Huronia.

ARRIVAL AT STE-MARIE AMONG THE HURONS

The treacherous northern water route via the Ottawa was another cruel initiation for Noel. The party reached the Residence of Ste-Marie on the Wye on September 7, 1644. Almost at once Noel Chabanel took up the study of the Huron language. For the next five years of his life Chabanel’s world was to be encompassed by his life at Ste-Marie and a few missionary excursions, working first with Jean de Brebeuf and finally with Charles Garnier.

Here at Ste-Marie, face to face with the harsh realities of the coun-try, Noel’s zeal was spurred when he met the veteran missionaries of Huronia. From time to time they returned from their mission outposts to Ste-Marie which served as their base of operations, their council chamber, their refuge and place of recollection, their haven for spiritual and social comfort.

THE LANGUAGE BARRIER

The Relation for this year informs us that Noel was destined at first to work with the nomadic Algonkins who were resident in the Huron dis-trict. After a winter’s hard work at learning the Indian language he came to a shocking realization. Try as he would, he could not master the intricate Indian tongue. Paul Ragueneau, his superior at Ste-Marie, best describes this tragedy. “Once here, even after three, four, five years of study of the Indian language, he made such little progress that he could hardly be understood even in the most ordinary conversation. This was no small mortification for a man burning with the desire to convert the Indians. Besides, it was particularly painful, for his memory had always been good, as were his other talents, which was proven by his years of satisfactory teaching of rhetoric in France.”

In one of the most touching documents of the Jesuit Relations, Ragueneau gives a poignant picture of the struggles of this heroic man who wrote of himself as a “bloodless martyr in the shadow of martyrdom.” To make matters worse his tastes were so delicate and sensitive that he found everything about the Indian customs and culture crude, foreign, even revolting. One would think that this is more than enough suffering for one man to bear. But there is more. “When in addition God withdraws His visible graces, and remains hidden, although a person sighs for Him alone and when He leaves the soul a prey to sadness, disgust and natural aversions; these are trials which are greater than ordinary virtue can bear.” Certain it is that, without the strength of God which Chabanel incessantly prayed for, his courage would have broken under the severe strain.

For five frightful years Chabanel had to endure this desolating martyrdom. During this agony Noel saw Brebeuf, Daniel, Garnier and others of his brothers competent and successful at their work. Here he was, frustrated before he could begin, denied the one essential tool for success – the ability to communicate with his native flock. Perhaps, though, the most bitter pill of all was the scorn and ridicule the natives heaped on him for his courageous but abortive attempts to speak their language – this, even from the children! He seemed easy prey to the subtle temptation assailing him again and again to leave this primitive country and return to France where there was plenty of work more suited to his character and talents.

Yet, Noel, though severely tested, refused to come down from the cross on which God had placed him. In fact to bind himself more irrevocably to his cross he made a vow to remain on it for life. The Relation of 1650 preserves for us the wording of this vow which he pronounced at Ste-Marie on June 20, 1647 on the Feast of Corpus Christi. It is worth quoting in full as it reveals the steely quality of this person who, though sensitive by nature, by God’s grace persevered to the bitter end.

“My Lord, Jesus Christ, Who, by the admirable dispositions of Divine Providence, hast willed that I should be a helper of the holy apostles of this Huron vineyard, entirely unworthy though I be, drawn by the desire to cooperate with the designs which the Holy Ghost has upon me for the conversion of these Hurons to the faith; I, Noel Chabanel, in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament of Your Sacred Body and Most Precious Blood, which is the Testament of God with man; I vow perpetual stability in this Huron Mission; it being understood that all this is subject to the dictates of the Superiors of the Society of Jesus, who may dispose of me as they wish. I pray, then, 0 Lord, that You will deign to accept me as a permanent servant in this mission and that You will render me worthy of so sublime a ministry. Amen.”

That heroic vow won for Chabanel, in this life, strength to endure every hardship, and, on the day of the canonization of the Martyrs, the distinction of standing as an equal beside those whom he regarded as his superiors. As Christ did in His passion, Noel repeated in his life the struggle against the powers of darkness, a struggle sustained only through persevering prayer.

Despite his crucifixion of loneliness and discouragement, with the support of his superior, Father Ragueneau, and his spiritual guide, Father Pierre Chastelain, Noel carried on, day by day, as best he could, serving in whatever way he could, but always in a secondary role, in the shadow of his more successful brother missionaries. While residing at Ste-Marie, 1644 to 1645, Chabanel found innumerable tasks to keep him busy, ministering to the many needs in the European residence and the Indian compound. Was a companion needed to go to one of the missionary stations? To help in the Indian hospital, to baptize, to assist the dying, to catechize the children? Chabanel was always ready to do his humble best.

OSSOSSANE’, MISSION OF LA CONCEPTION

In 1646 Noel was sent to the mission of the Immaculate Conception at Ossossane’, called La Rochelle by the French, on Nottawasaga Bay south west of Ste-Marie. So Christian was this Huron village that it was called the “believing village” by the natives. In three years time, 1649, from this village some three hundred Huron warriors were to put up a courageous last ditch stand against a thousand Iroquois before they were eventually wiped out at the village of St. Louis. Working here under Simon le Moyne, Chabanel found a model mission well advanced in Christianity. Besides, he could visit from time to time his “oasis of peace,” Ste-Marie, a short distance away where he could consult with his spiritual adviser, Pierre Chastelain, SJ.

On Oct. 21,1646 Noel pronounced his final vows as a Jesuit, promising before Paul Ragueneau the superior his “perpetual obedience in the Society of Jesus.” While Chabanel was making his spiritual immolation to his Lord, unknown to him and his brothers, a mere two days before in New York State Isaac Jogues and John de la Lande had already offered their life’s blood to the same Christ Noel was serving in a bloodless martyrdom. Only too soon the shadow of the cross which had already enveloped three martyrs of that glorious band of eight would reach into Huronia to claim yet five more victims for the sacrifice.

During his stay at Ossossane’ Noel met Charles Garnier on his way to establish a new mission, the farthest outpost, among the Petun nation about fifty miles south west of Ste-Marie. Little did Noel think that one day he would join Garnier in that mission and finally gain the coveted palm of martyrdom for which he longed and of which he deemed himself so unworthy.

BACK TO STE-MARIE

In the spring of 1647, he was recalled to Ste-Marie to help with the stream of Huron refugees who fled there panic stricken from the invading Iroquois. It was while here in June that he made his annual retreat and pronounced his heroic vow of stability in the Canadian mission. Though he did not possess the gift of the Huron tongue as did Brebeuf, though he did not have the charm to attract the Indians as did Garnier and Daniel, Noel asked but the grace to persevere till death as a helper of these holy missionaries.

From 1647 to 1648 Chabanel humbly and obediently carried out his appointed tasks both at Ste-Marie and in the various mission villages dependent on Ste-Marie. That year of 1648 the shadow of the Iroquois menace darkened the skies of Huronia. The enemy were closing in taking first the outlying missions. On July 4th, tragedy struck closer to home base. Teanaostaiae, the mission of St. Joseph, eleven miles south east of Ste-Marie was seized and destroyed by the Iroquois. Anthony Daniel, its amiable pastor fell defending his flock. Panic spread throughout Huronia. St. Ignace I, because of the Iroquois danger was moved closer to Ste-Marie about six miles to the east on the Sturgeon River. Brebeuf was the master builder of St. Ignace II and was put in charge of this station along with its sister mission, St. Louis, half way between the new St. Ignace II and Ste-Marie. He asked for missionary help. Father Ragueneau sent him Noel Chabanel.

AT ST. IGNACE II

In the autumn of 1648 Noel left Ste-Marie to join Brebeuf at St. Ignace. He worked with Brebeuf until February, 1649, considering it a great privilege to be associated with this giant so courageous by nature and so endowed by grace. There was work to be done that fall and winter to put the finishing touches to St. Ignace II. The weeks flew by. In February, 1649, Father Chabanel was replaced by the frail and delicate Gabriel Lalemant, a novice of but a few months in Huronia. Chabanel, more robust in health was needed in the hardy mission of the Petuns, St. Jean, to the south west near modern Stayner, to help Charles Garnier. Accustomed by now to these quick changes Noe~~l left for his new mission post on February 17, sad to leave Bre’beuf, but without a murmur.

As Noel took his last leave of Ste-Marie, his final farewell to Father Chastelain betrayed a premonition of martyrdom. “This time I hope to give myself to God once and for all and to belong to Him entirely.” Shortly after, Chastelain remarked to a friend, “I have just been deeply moved. That good Father spoke to me with the look and voice of a victim offering up his sacrifice. I do not know what God has in store for him, but I can see that He wants him to be a great saint.”

ST. JEAN AMONG THE PETUNS

Hardly had Noel spent a month at his new post when the shocking news reached him that the Iroquois had attacked and ravaged St. Ignace and St. Louis on March 16. Both Brebeuf and Noel’s replacement Gabriel Lalemant, were martyred. In a touching letter to his Jesuit brother, Pierre, Noel wrote betraying his wistful yearning: “Father Gabriel Lalemant. . . had replaced me at the village of St. Louis just a month before his death, while I, being stronger, was sent to a more distant and more difficult mission, but one not so fertile in palms and crowns as the one for which my laxity rendered me unworthy before God.” Robbed of the martyrdom he coveted when it was within his grasp! Surely this was the supreme test of his complete obedience to God’s pleasure. But no, a second time this was to happen, and soon!

COLLAPSE OF HURONIA

Tragedy and complete collapse came to Huronja that fatal year, 1649. With village after village pillaged by the Iroquois, with the total breakdown of Huron morale, with the mass hysteria and exodus of the Hurons from Huronia, the Jesuit missionaries came to a painful decision: without a flock what purpose was there in their staying! On May 15, Ste-Marie, the work of ten years, was abandoned and deliberately destroyed by the missionaries themselves. They and the remnant of their sheep resettled temporarily on St. Joseph (Christian Island). The new home was called Ste-Marie II.

All fall of 1649 Chabanel labored among the Petuns with Charles Garnier at St. Jean. On December 5th., he again received orders from his superiors, this time to leave St. Jean and make his way to Christian Island. There were two reasons for this decision: first, the extreme famine conditions among the Petuns, and secondly, his superiors felt they should not expose two missionaries in this dangerous outpost..

Obedience was by now second nature to Chabanel. He bade farewell to Garnier on December 5th., and immediately headed north towards Christian Island. Two days later he feared that St. Jean had fallen to the Iroquois and that Garnier had won a martyr’s crown. A second time was Chabanel cheated of martyrdom! But this time he was not to be denied for long.

The day following Garnier’s death, December 8th., Feast of the Immaculate Conception, Noel Chabanel’s life of “bloodless martyrdom” ended in a martyrdom of blood.

INITIAL MYSTERY SURROUNDING NOEL’S DEATH

At first the details of Noel’s disappearance were vague and uncertain. But thanks to the painstaking care and precision of his chief chronicler, Paul Ragueneau, we are now able to reconstruct the sequence of events leading up to Noel’s martyrdom. There are two accounts of Noel’s death written by Ragueneau. The first, in the 1650 Relation, written shortly after Noel’s disappearance, recounts his death but reveals no knowledge of the motives for the slaying. Only months later did the real story come to Ragueneau. This more accurate information was the basis of his second account.

THE FIRST ACCOUNT

The first account as given by Ragueneau in the 1650 Relation goes as follows. On Dec. 5th., 1649 Noel, as ordered, left St. Jean to proceed to Christian Island. On his way north he stopped at the village of St. Matthias, a Petun mission where two Fathers, Greslon and Garreau were stationed. It was here Noel spoke his last recorded words to Father Garreau who had sailed to New France with him six years previously. On the morning of Dec. 7th., he left them accompanied by seven or eight christian Hurons. After covering a distance of six long leagues over difficult wintry roads night came upon them. While his companions slept, Noel remained awake to pray. Suddenly the silence of the night was pierced by shouts and noises. Some of these came from the victorious Iroquois who had ravaged St. Jean; some came from the prisoners taken there. Noel quickly awakened his companions who immediately scattered in flight leaving Chabanel alone. The Christians who had escaped from danger reached the Petun nation and reported that Noel tried to follow them, but when he could no longer keep up with them, fell on his knees saying: “What difference does it make if I die or not? This life does not count for much. The Iroquois cannot snatch the happiness of heaven from me.”

At daybreak (December 8th.) Chabanel continued north towards his destination, Christian Island. (From this point on the testimony becomes garbled and untrustworthy, as Ragueneau suspected and was to confirm later.) One of the Hurons said he saw Father Chabanel standing on the bank of a river which lay across his path (the Notta-was aga). This witness added that he had passed Chabanel in his canoe and that he saw Noel throw away his coat, sack and blanket in order to expedite his escape. Ragueneau remarks, “Since that time we have not been able to get news of the Father. We cannot be sure how he died.” He then gives three possibilities: Noel fell into the hands of the enemy who killed him; perhaps he lost his way and died of hunger and cold; or, more probably, he was killed by the Huron who was the last to see him. This man had been a Christian and had since become an apostate who was quite capable of killing Noel to rob him of his little possessions.

Ragueneau concludes his first account by saying that he felt it wiser in this time of public calamity to stifle their suspicions – their only concern being the service of God. Prudent, sober man that he was, he strongly doubted the testimony of this apostate Huron who was known to be no angel.

THE SECOND ACCOUNT

Now for the second, more informed account, of Chabanel’s death, written in 1652 from Quebec. This is found in an autograph note of Paul Ragueneau, appended to the precious MS of 1652, and affirmed under oath. This testimony clears up the first obscurity of Noel’s death. Ragueneau testifies that he obtained from most trustworthy witnesses the following details. The Huron apostate named Louis Honareenhax finally publicly confessed, and even bragged that he had killed Father Noel with a hatchet blow and thrown his body in the half frozen Nottawasaga river, out of hatred for the faith.

For, ever since he and his family had embraced the faith, all kinds of misfortunes had befallen them. These he blamed on Chabanel and in his superstition believed he had rid his people of a menace. It was also a known fact that Louis had been a trouble maker and had previously tried to stir up his tribesmen to get rid of Chabanel and Garnier.

This clear testimony made under oath by a man of Ragueneau’s integrity leaves no doubt as to the real slayer of Noel and the true motivation for his crime, namely out of hatred for the faith on which he blamed all his troubles. Ragueneau himself was certain his friend Chabanel had died a martyr.

EPILOGUE

Thanks to Raguencau the long silence shrouding the greatness of Noel Chabanel has been broken.

Only in the twentieth century is Noel Chabanel’s poignant life and unique martyrdom coming to be appreciated. Like the life of the suffering Christ he served so faithfully, Noel’s life seemed one of apparent failure. Noel Chabanel is the silent hero of the hard trail, a patron of misfits, patron of the lonely, disappointed and abandoned, the patron of all square pegs in round holes. In the official picture (iconography) of the Jesuit Martyrs of North America, the closed book in his hand is a grim symbol of his life.

Because of Noel’s heroic obedience to and generous acceptance of God’s will, God, Who is never outdone in generosity, rewarded him with the glory of martyrdom. Like his Master, Noel died as he lived, a lonely man, a man in the shadows. Somewhere along the snow-covered path by the Nottawasaga river, Noel’s grim trail merged into the green pastures of eternity. He was struck down in the dark night by an apostate Huron’s tomahawk and his body thrown into the Nottawasaga River. There perhaps somewhere along its murky bottom lie the bodily remains of this unique man. And so at the age of thirty-six years, nineteen as a Jesuit, five as a Huron missionary, Noel Chabanel, one of the “little four” merited to be crowned a martyr and saint alongside the “big four.”

Our modern world, shocked with the rapidity of constant change, needs more saints of the calibre of Noel Chabanel.

Noel Chabanel, obedient throughout life, persisted obedient unto death because he was a man of unshakable faith and persevering prayer, a man, therefore, who refused to quit in the face of overwhelming odds. The call to faith is a call to obedience, a call to adjust to the new and trying situations God is continually moving man into, a call to resist the powers of darkness that subtly tempt man to come down from the cross of his human condition.”

Saint Noël Chabanel, whose heart burned with the desire to sacrifice all for the glory and honor of God, obtain for me a right appreciation of the trials and sufferings of this life.

Let not disappointments discourage me nor crosses weigh me down, so that strengthened by the example of your heroic constancy and perseverance in the service of God on earth, I may some day share your reward in heaven. Amen.

(-please click on the image for greater detail)

“Today we enter upon the observance of Lent, the season now presented to us in the passage of the liturgical year. An appropriately solemn sermon is your due so that the word of God, brought to you through my ministry, may sustain you in spirit while you fast in body and so that the inner man, thus refreshed by suitable food, may be able to accomplish and to persevere courageously in the disciplining of the outer man.

For, to my spirit of devotion, it seems fitting that we, who are about to honor the Passion of our crucified Lord in the very near future, should fashion for ourselves a cross of the bodily pleasures in need of restraint, as the Apostle says: “And they who belong to Christ have crucified their flesh with its passions and desires. ” (Gal. 5:24)

In fact, the Christian ought to be suspended constantly on this cross through his entire life, passed as it is in the midst of temptation. For there is no time in this life when we can tear out the nails of which the Psalmist speaks in the words: “Pierce thou my flesh with thy fear.”

Bodily desires constitute the flesh, and the precepts of justice, the nails with which the fear of the Lord pierces our flesh and crucifies us as victims acceptable to the Lord. Whence the same Apostle says: ‘I exhort you therefore, brethren, by the mercy of God, to present your bodies as a sacrifice, living, holy, pleasing to God.” (Rom 12:1)

Hence, there is a cross in regard to which the servant of God, far from being confounded, rejoices, saying: “But as for me, God forbid that I should glory save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom the world is crucified to me, and I to the world.” (Gal. 6:14)

That is a cross, I say, not of forty days’ duration, but of one’s whole life, which is symbolized by the mystical number of forty days, whether because man, about to lead this life, is formed in the womb for forty days, as some say, or because the four Gospels agree with the ten-fold Law and four tens equal that number, showing that both the Old and New Testaments are indispensable for us in this life, or it may be for some other and more likely reason which a keener and superior intellect can fathom.

Hence, Moses and Elias and our Lord Himself fasted for forty days so that it might be suggested to us that in Moses and in Elias and in Christ Himself, that is, in the Law and the Prophets and the Gospel, this penance was performed just as it is by us, and so that, instead of being won over to and clinging to this world, we might rather put to death the old man, “living not in revelry and drunkenness, not in debauchery and wantonness, not in strife and jealousy. But [let us] put on the Lord Jesus, and as for the flesh, take no thought for its lusts.” (Rom. 13:13-14)

Live always in this fashion, O Christian; if you do not wish to sink into the mire of this earth, do not come down from the cross. Moreover, if this ought to be done throughout one’s entire life, with how much greater reason should it be done during these forty days in which this life is not only passed but is also symbolized?

Therefore, on other days let not your hearts be weighed down with self-indulgence and drunkenness, but on these days also fast. On other days do not commit adultery, fornication, or any unlawful seduction, but on these days also refrain from that conjugal pleasure which is lawful.

What you deprive yourself of by fasting add to your almsgiving; the time which was formerly taken up with conjugal duties spend in conversation with God; the body which was engaged in carnal love prostrate in earnest prayer; the hands which were entwined in embraces extend in supplication. You, who fast even on other days, increase your good works on these days. You, who crucify your body by perpetual continency on other days, throughout these days cleave to your God by more frequent and more fervent prayer.

Let all be of one mind, all faultlessly faithful while on this journey, breathing with desire and burning with love for their one country. Let no one envy in another or belittle the gift of God which he himself lacks. Rather, where spiritual blessings are concerned, consider as your own what you love in your brother and let him, in turn, consider as his own what he loves in you.

Let no one, under pretense of abstinence, aim at merely changing rather than eliminating pleasures, so that he seeks costly food because he is abstaining from meat, and rare liquors because he is not drinking wine, lest in the process, as it were, of taming the flesh he give greater rein to the demands of pleasure. Indeed, for the clean all food is clean, but for no one is luxury clean.

Above all else, my brethren, fast from strife and discord. Keep in mind the words used by the Prophet in his vehement denunciation of certain persons: “ln the days of your fast your own wills are found because you torment all who are under your power and you strike with your fists ; your voice is heard in outcry.” Continuing in the same strain, he adds: “Not such a fast have I chosen, saith the Lord.” (Is. 58:3-5)

If you desire to cry aloud, then have recourse to that appeal of which the Scripture says: “I cried to the Lord with my voice.” (Ps. 142:1) That voice is certainly not one of strife, but of charity; not of the flesh, but of the heart. Neither is it that cry of which Isaias says: “I waited for him to make a judgment, but he has worked iniquity, not justice but a cry.”(Is:5:7)

“Forgive, and you shall be forgiven; give, and it shall be given to you.” (Lk 6:37-38)

These are the two wings of prayer on which one flies to God : if any fault is committed against him, he forgives the offender and he gives alms to the needy.”

–St Augustine of Hippo (Sermon 205)

Love,

Matthew