“I am sorrowful, even unto death.” Mt 26:38

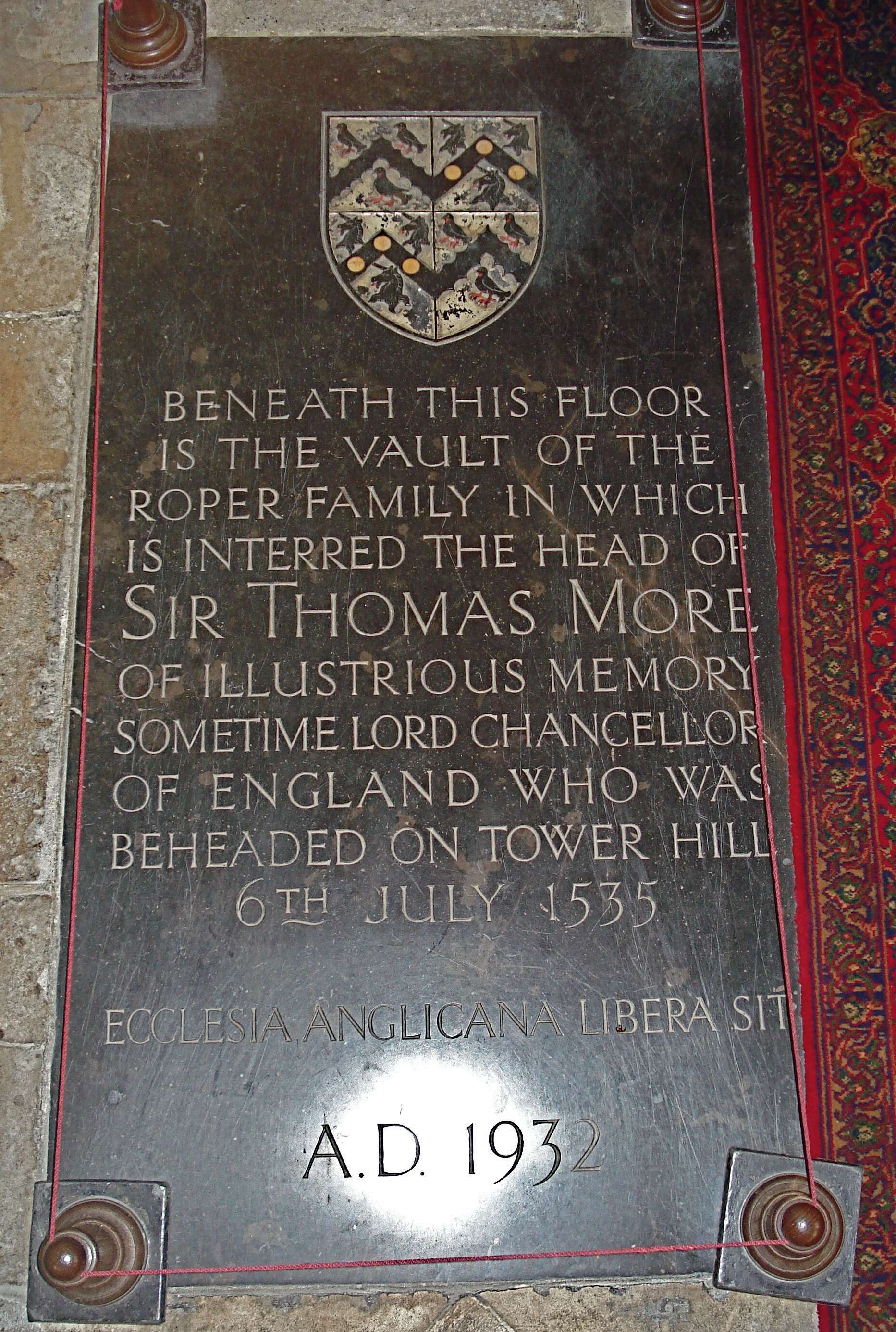

The History of the Passion closes the long list of works, both Latin and English, written by St. Thomas More. His imprisonment in the Tower lasted from April 17 , 1534, to July 6, 1535, the day of his martyrdom.

From the beginning he knew that he was never likely to regain his freedom and determined to make the best possible use of his time as a preparation for death. In all sincerity he expressed his satisfaction at obtaining so valuable a period of quiet and recollection for prayer and study.

To Margaret Roper, his beloved daughter, he wrote of his appreciation of the grace of God that ‘hath also put in the king towards me that good and gracious mind, that as yet he hath taken from me nothing but my liberty, wherewith (as help me God) his grace hath done me great good by the spiritual profit that I trust I take thereby, that among all his great benefits heaped upon me so thick I reckon, upon my faith, my imprisonment even the very chief.’ 1

Similarly on another occasion he said to her: ‘They that have put me here ween they have done me a high displeasure.’… ‘I find no cause, I thank God, Meg, to reckon myself in worse case here than in my own house. For methinketh God maketh me a wanton and setteth me on his lap and dandleth me.’ 2

He had spent long years in writing against the new heresies the controversial books which form the bulk of his English works, but now, although occasional references to current controversies are still to be found, his chief preoccupation is to prepare himself, and his family, too, for the inevitable separation of death. Thus did he write the Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation and the History of the Passion.

Devotion to our Lord’s passion was familiar to him. ‘Every year on Good Friday,’ writes Stapleton, ‘he called together the whole of his family into what was called the New Building, and there he would have the whole of our Lord’s passion read to them, generally by John Harris. From time to time More would interrupt the reading with a few words of pious exhortation.’ 3 It may well be that in the present work we have echoes of those exhortations. Another clue to their contents may perhaps be provided by More’s words to Tyndale: ‘Who can speak of Christ’s passion and speak nothing of His mercy?’ 4

Pico of Mirandula, whom More in his early years had chosen as a model, upon his death-bed gazed upon the crucifix, ‘that in the image of Christ’s ineffable passion, suffered for our sake, he might, ere he gave up the ghost, receive his full draught of love and compassion in the beholding of that pitiful figure, as a strong defence against all adversity, and a sure portcullis against wicked spirits.’ 5

More, too, wished his last thoughts to be with his crucified saviour. To Cromwell, who examined him concerning the new statute by which the king was declared supreme head of the Church, he replied: ‘I have fully determined with myself neither to study nor meddle with any matter of this world, but that my whole study should be upon the passion of Christ and mine own passage out of this world.’ 6

From the number of references to our Lord’s passion in the letters which he wrote during his imprisonment it is clear that he kept this resolution faithfully. Thus speaking of his death he says : ‘The fear thereof, I thank our Lord, the fear of hell, the hope of heaven, and the passion of Christ daily more and more assuage.’ And in the same letter: ‘I beseech Him to…give me grace and you both in all our agonies and troubles devoutly to resort prostrate unto the remembrance of that bitter agony which our Saviour suffered before His passion at the mount. And if we diligently do so, I verily trust we shall find therein great comfort and consolation.’ 7 In another he writes of the fall of St. Peter who ‘fell in such fear soon after, that at the word of a simple girl he forsook and forswore our Saviour,’ and takes warning to himself by the example. 8

The Dialogue of Comfort, written at the same time, bears similar witness to the constant preoccupation of his mind with our Lord’s passion. It is not too much to say that the moving passage on the subject in the last chapter is the grand climax towards which everything else in the book leads. ‘If we could and would,’ he writes, ‘with due compassion conceive in our minds a right imagination and remembrance of Christ’s bitter painful passion, of the many sore bloody strokes that the cruel tormentors with rods and whips gave Him upon every part of his holy tender body, the scornful crown of sharp thorns beaten down upon His holy head, so straight and so deep that on every part His blessed blood issued out and streamed down, His lovely limbs drawn and stretched out upon the cross to the intolerable pain of His forebeaten and sore beaten veins and sinews, new feeling, with the cruel stretching and straining, pain far passing any cramp in every part of His blessed body at once, then the great long nails cruelly driven with hammers through His holy hands and feet, and in this horrible pain lift up and let hang, with the peise (weight) of all His body bearing down upon the painful wounded places, so grievously pierced with nails, and in such torment (without pity, but not without many despites), suffered to be pined and pained the space of more than three long hours, till Himself willingly gave up unto His Father His holy soul, after which yet to shew the mightiness of their malice after His holy soul departed they pierced His holy heart with a sharp spear, at which issued out the holy blood and water whereof His holy sacraments have inestimable secret strength: if we would, I say, remember these things in such wise, as would God we would, I verily suppose that the consideration of His incomparable kindness could not in such wise fail to inflame our key-cold hearts, and set them on fire in His love, that we should find ourselves not only content, but also glad and desirous, to suffer death for His sake that so marvellous lovingly letted not to sustain so far passing painful death for ours.’ 9

Passio Christi, conforta me , prays St. Ignatius, ‘Passion of Christ, strengthen me.’ It was from his meditations upon our Lord’s passion that St. Thomas drew the strength to suffer martyrdom. To the very end it was his comfort and his support. Thus he set out upon his last journey up Tower Hill with a cross in his hand, and in his reply to the good lady who offered him wine showed how his thoughts were with Him who died for us upon the cross. ‘Christ in His passion,’ he said, ‘was given not wine, but vinegar to drink.’ 10

1 English Works , 1557, p. 1442 E.

2 Roper’s Life of More , E.E.T.S., p. 76.

3 Life of Sir T. More , Eng. trans., p. 96.

4 E.W. , p. 408, B.

5 ibid., p. 8, F.

6 ibid., p. 1452, A.

7 ibid., p. 1431, E. and H.

8 ibid., p. 1442, G.

9 E.W., p. 1260, E.

10 Stapleton, l.c. 209.

Sir Thomas More’s Psalm on Detachment

(Written while imprisoned in the Tower of London, 1534)

Give me Thy grace, good Lord:

To set the world at nought;

To set my mind fast upon Thee,

And not to hang upon the blast of men’s mouths;

To be content to be solitary,

Not to long for worldly company;

Little and little utterly to cast off the world,

And rid my mind of all the business thereof;

Not to long to hear of any worldly things,

But that the hearing of worldly phantasies may be to me displeasant;

Gladly to be thinking of God,

Piteously to call for His help;

To lean unto the comfort of God,

Busily to labor to love Him;

To know mine own vility and wretchedness,

To humble and meeken myself under the mighty hand of God;

To bewail my sins passed,

For the purging of them patiently to suffer adversity;

Gladly to bear my purgatory here,

To be joyful of tribulations;

To walk the narrow way that leadeth to life,

To bear the cross with Christ;

To have the last thing in remembrance,

To have ever afore mine eye my death that is ever at hand;

To make death no stranger to me,

To foresee and consider the everlasting fire of hell;

To pray for pardon before the Judge come,

To have continually in mind the passion that Christ suffered for me;

For His benefits uncessantly to give Him thanks,

To buy the time again that I before have lost;

To abstain from vain confabulations,

To eschew light foolish mirth and gladness;

Recreations not necessary — to cut off;

Of worldly substance, friends, liberty, life and all, to set the loss

at right nought for the winning of Christ;

To think my most enemies my best friends,

For the brethren of Joseph could never have done him so much good with their love and favor as they did him with their malice and hatred.

These minds are more to be desired of every man than all the treasure of all the princes and kings, Christian and heathen, were it

gathered and laid together all upon one heap.

-from Complete Works of St. Thomas More , vol. 13 (Yale University Press, 1976), pp. 226-227). Modernized in Sadness of Christ and Final Prayers and Instructions (Scepter Press, 1993), pp. 148-150).

Love, and praying, wishing for you a blessed & spiritually fruitful Lent,

Matthew