– detail from the “Last Judgment”, by Giotti, Cappella Scrovegni, 1306, Fresco, 1000 x 840 cm, Arena Chapel, Padua, Italy, please click on the image for greater detail.

– detail from the “Last Judgment”, by Giotti, Cappella Scrovegni, 1306, Fresco, 1000 x 840 cm, Arena Chapel, Padua, Italy, please click on the image for greater detail.

The chapel is entered from the west, the side on which the sun goes down. In accordance with an old tradition, the entrance wall of the chapel is filled by the depiction of the Last Judgment. This scene is as complex and crowded as the frescoes on the side walls are concentrated and reduced to essentials. This large painting occupies the entire west wall across several registers. The three-light windows of the façade also had to be incorporated into the composition.

This extensive depiction of the Last Judgment is dominated by the large Christ in Majesty at its centre. The twelve apostles sit to His left and to His right. Here the two levels divide: the heavenly host appears above, people plunge into the maw of hell below, or are led by angels towards heaven.

The way this large fresco is divided into registers is traditional. But if we look at Giotto’s invention in detail, then his novel attempts at visualizing different spheres, as well as abstract beliefs, become particularly apparent. In the center of the representation, Christ is enthroned as supreme Judge in a rainbow-colored mandorla. The deep, radiant gold background, the style of painting, and the delicate substance give the impression that the heavens have opened in order to reveal the powerful, extremely solidly modeled figure of Christ. Different levels are likewise alluded to when the choirs of angels disappear behind the real window, or when the celestial watch in the upper area of the picture rolls back the firmament, behind which the golden-red doors of the heavenly Jerusalem shine forth. The black and red maw of hell, which seems to anticipate Dante’s “Inferno”, is different again in its impact.

-by www.catholicfaithandreason.org

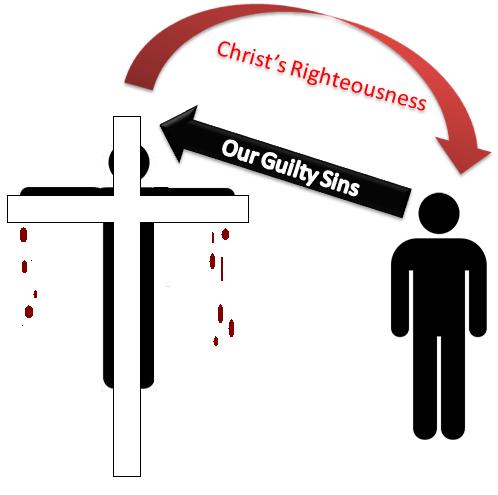

1) What is Justification? To be justified means being made righteous, just, holy, and acceptable before God. Because we are born in original sin, we need to be made right with God and only He can effect this change, which was merited by the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross, but which we must accept (or in the case of an infant, their parents) by sincere repentance (Luke 24:47; Acts 2:38; 3:19; 17:30; Romans 2:4; 1 Corinthians 7:9-10, etc.) and by baptism, by which sacrament we become children of God and heirs with Christ (John 1: 12; Romans 8:14-17).

It is the gift of divine sonship. Our soul is regenerated (made clean) from the effects of original sin (or mortal sin if any has been committed) and wiped clean. Thus, there is cooperation between God’s grace and man’s freedom that is expressed by the assent of faith (Catechism of the Catholic Church or CCC 1993). “With justification faith, hope and charity are poured into our hearts, and obedience to the divine will is granted” (CCC 1991). “In baptism you were not only buried with him, but also raised to life with him because you believed in the power of God who raised him from the dead” (Colossians 2:12; Romans 6:3-5,8).

2) Salvation is a gift of God. Man cannot obligate God. But man is called upon to freely choose God through an exercise of his free will. The steps for an adult:

(1) God grants the grace to believe (prevenient grace)

(2) Man with his free will accepts it, repenting of sins committed and affirming in faith God’s truth

(3) Man cooperating with divine grace receives baptism

(4) Baptism re-generates the soul so that the man is “born from above” or “born again”

(5) We can co-operate with the sanctifying grace in our souls or not.

3) What is grace? Grace is first and foremost the gift of the Spirit who justifies and sanctifies us. But grace also includes the gifts that the Spirit grants us to associate with his work, to enable us to collaborate in the salvation of others and in the growth of the Body of Christ in the Church.” (CCC 2003). The Apostle Peter gives us an example of how people are saved after Pentecost when the sermon he preaches leads them to want salvation. He says:

“‘Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit….’ So those who received his word were baptized, and there were added that day about three thousand souls.” (Acts 2: 38, 41)

St. Augustine, an Early Church Father, put it this way:

“Indeed we also work, but we are only collaborating with God who works, for his mercy has gone before us. It has gone before us so that we may be healed, and follows us so that once healed, we may be given life; it goes before us so that we may be called, and follows us so that we may be glorified; it goes before us so that we may live devoutly, and follows us so that we may always live with God: for without him we can do nothing” (De natura et gratia, 31).

4) A Catholic monk in the 16th century made the novel claim that we are saved by “faith alone.” The lense of Fr. Martin Luther was doubtless his own spiritual turmoil. He viewed God as a very harsh judge but he was not tracking with Scripture in this conclusion. His own sensitive conscience led him to live in fear that this harsh God would judge him and find him wanting. He felt he might never enter heaven, until he read the words of St. Paul one day in light of his own fearful struggle, and came to a new interpretation, in fundamental discontinuity with the previous 1500 years of Apostolic Tradition. A detailed sympathetic study by Protestant scholar Alister McGrath admits that Luther’s thesis of sole fide, by faith alone, was a brand new theology. It was a new approach to salvation that removed much of man’s moral responsibility for his salvation. No Christian theologian before Luther ever held it.

Luther thought man should sin “boldly” telling Melanchthon in a letter in 1521, “No sin can separate us from Him, even if we were to kill or commit adultery thousands of times each day.” Some argue this hyperbole to make the point that we must trust in God, however, this directly contradicts Holy Scripture wherein St. Paul wrote, “What shall we say then? Are we to continue in sin that grace may abound? By no means! How can we who died to sin still live in it?” (Romans 6:1-2).

Ironically, among Protestant groups today, the Lutheran view is closest to the Catholic. For example, Luther taught the necessity of Baptism (including infant Baptism) and the possibility of losing one’s salvation and the real presence in the Eucharist (though he spoke of consubstantiation rather than transubstantiation). Both agree that justification takes place solely by [by faith through] God’s grace (Joint Declaration with the World Lutheran Federation, 1999). “The working of God’s grace does not exclude human action: God effects everything, the willing and the achievement, therefore we are called to strive” (cf. Phil. 2:12ff). The Holy Spirit effects in the one justified an active love (an inward renewal). Thus, what we do in God’s grace can merit for Christ abides in us.

Still, what Luther produced was a heresy. It comforted Luther and comforts many today, but is a misreading of Scripture, nonetheless. Why is it comforting compared to Catholic doctrine? It amounts to an abnegation of moral responsibility and what Protestant Dietrich Bonhoeffer once termed “cheap grace.” He wrote: It means the forgiveness of sins proclaimed as a general truth, the love of God taught as the Christian ‘conception’ of God. An intellectual sassent to that idea is held to be of itself sufficient to secure the remission of sins . . . . In such a Church the world finds a cheap covering for its sins; no contrition is required, still less any real desire to be delivered from sin. Cheap grace therefore amounts to a denial of the living Word of God. . . . Cheap grace means the justification of sin without the justification of the sinner” (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship)

Luther so believed that he was correct that he even changed Scripture to reflect his interpretation, changing Romans 3:28 from: “For we hold that a man is justified by faith apart from works of law” to “For we hold that a man is justified by faith alone apart from works of law.” Luther thought the intent of the words urgently demanded this assertion, but he nonetheless tampered with the Word of God. He did not like what he saw in the letter of James either (who wrote, “For as the body apart from the spirit is dead, so faith apart from works is dead”) calling it an “epistle of straw.”

5) James says that we are justified by works also:

“Was not Abraham our father justified by works, when he offered his son Isaac upon the altar? You see that faith was active along with his works, and faith was completed by works, and the scripture was fulfilled which says, ‘Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness’; and he was called the friend of God. You see that a man is justified by works and not by faith alone. And in the same way was not also Rahab the harlot justified by works when she received the messengers and sent them out another way? For as the body apart from the spirit is dead, so faith apart from works is dead. (James 2:21-26)

Were St. Paul and St. James at odds with one another? They are not. Paul is addressing the fact that grace is needed to believe and James is talking about the Christian who already believes, but nonetheless has a necessity to have a faith animated by good works. Understanding the works that Paul refers to as “works of the law” is critical. Here he refers to the Old Law, especially circumcision, which has no power to save anyone. He is teaching that salvation is by God’s grace, not by any works that merit God’s favor. [We know this from the Dead Sea scrolls, written in Christ’s time or before, which clearly show the usage and meaning of “works of law” as works of the Mosaic law, like circumcision and animal sacrifice.] Faith is a gift from God, but James, is showing that faith without works is dead. Scripture says that even the devil believes but that does not merit him anything (James 2: 19).

In the words of St. Augustine, God created us without our cooperation, but He will not save us without it. So we are saved by faith, hope and charity. The supernatural love of God is what unites the soul to God! “Salvation in Christ is conditional; it requires repentance and faith.” Good works are the fruit of salvation. (Jimmy Akins, “Justification: Setting the Record Straight,” click here)

6) We must read all that Scripture says about salvation. St. Paul, for example, writes: “For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision is of any avail, but faith working through love (Galatians 5: 6)

And again:

“And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing” (1 Corinthians 13: 2). Note: Open your Bible and read all of 1 Corinthians 13 and see what kind of love St. Paul is talking about.

7) Love requires obedience according to Jesus: “If you love me, you will keep my commandments.” Or again in Matthew 19: 16-17:

“And behold, one came up to him, saying, ‘Teacher, what good deed must I do, to have eternal life?’ 17 And he said to him, ‘Why do you ask me about what is good? One there is who is good. If you would enter life, keep the commandments.'”

8) The Catholic teaching is that justification is a process by which we become righteous by God’s grace, but is not finished until we persevere to the end of our lives. Thus, we are justified by faith and obedience persevered in to the end. We must as St. Paul says, finish the race (2 Timothy 4:7). We do not work our own way to heaven because we are totally dependent upon the gift of faith and the grace of Christ, but our obedience is required. St. Paul begins and ends his epistle to the Romans by noting the importance of the “obedience of faith.”

9) The pattern in Scripture is troubling to the notion of faith alone. The pattern in Scripture is always faith and obedience leading to blessing. Would Noah and his family have been delivered from the flood by faith alone? Were they called upon to believe God or to believe and obey? Both. Noah had to build an ark. Did Abraham receive the promises that God made to him by faith alone? In Genesis 12, the Lord asked Abram to leave his home in Haran and go to distant land he did not know. He believed what God said to him and he obeyed and received the blessing in the form of a covenant promise by God. He was justified. Abraham’s obedience is most often spoken of as the reason God will bless him. In Genesis 22: 15-18:

“By myself I have sworn, says the Lord, because you have done this, and have not withheld your son, your only son, I will indeed bless you, and I will multiply your descendants as the stars of heaven and as the sand which is on the seashore. And your descendants shall possess the gate of their enemies, and by your descendants shall all the nations of the earth bless themselves, because you have obeyed my voice.”

God elevates this to a covenant oath in Genesis 26: 4-5:

“I will multiply your descendants as the stars of heaven, and will give to your descendants all these lands; and by your descendants all the nations of the earth shall bless themselves: because Abraham obeyed my voice and kept my charge, my commandments, my statutes, and my laws.”

So in Abraham we see that justification is a process, not a one-time event.

How about the Israelites being freed by God from Egyptian slavery and given the land of milk and honey, that today we call Israel by faith alone? Was that the case? No, they had to slaughter the lamb, smear the blood on the door posts, cross the Red Sea, and after they worshiped the golden calf, they had to follow Moses in the desert for 40 years, rely upon God to guide them and feed upon the manna provided by God, etc.

How about the leper Naman? Was he cleansed by faith alone? No, he had to dip in the water; he had to obey. Faith and obedience go together. Israel was God’s chosen nation and if God wanted to teach the world that they are to be saved by faith alone, than why did he fill the Bible with stories of those who are saved by faith and obedience?

10) Does our obedience mean that God does not deserve all the glory? No. Noah had to be build an ark to be saved but his deliverance was due to God and thus God gets the glory. We honor Abraham because of his faith and his obedience, but God gets the glory. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) says,

1999 “The grace of Christ is the gratuitous gift that God makes to us of his own life, infused by the Holy Spirit into our soul to heal it of sin and to sanctify it. It is the sanctifying or deifying grace received in Baptism. It is in us the source of the work of sanctification:

Therefore if any one is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old has passed away, behold, the new has come. All this is from God, who through Christ reconciled us to himself … (2 Corinthians 5: 18)

11) Summary. There are a large number diverse Scriptural verses relating to the topic of our salvation in Holy Scripture. If Jesus meant to teach faith alone he said so many things to confuse us. For example, in the Bread of Life discourse, John 6: 53-56:

“So Jesus said to them, ‘Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him.”

It is the same with St. Paul who wrote, “For he will render to every man according to his works . . . For it is not the hearers of the law who are righteous before God but the doers of the law who will be justified” (Rom 2: 6-10, 13).

The same is true in James, St. John or Peter, etc. St. Peter boldly says that Baptism saves you (see 1 Peter 3:21). The pattern is always the same. God is always saying I love you, I want to bless you, therefore, humble yourself before me, like a child trust me and obey me and I will deliver the blessing for you. As St. Paul said, “Therefore, my beloved, as you have always obeyed, so now, not only as in my presence but much more in my absence, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling; for God is at work in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure” (Philippians 2:12-13). One could give a whole sermon on that verse!

If asked, “Are you saved?” Respond according to the Bible I have been saved (Rom. 8:24, Eph. 2:5B,8), but I am also being saved (1 Cor. 1:8, 2 Cor. 2:15, Phil. 2:12), and I hope to be saved (1 Cor. 1:8, 2 Cor. 2:15, Phil. 2:12).

Quotations from the Early Church Fathers:

“We have learned from the prophets, and we hold it to be true, that punishments and chastisements, and good rewards, are rendered according to the merit of each man’s actions. Since if it be not so, but all things happen by fate, neither is anything at all in our own power. For if it be fated that this man, e.g., be good, and this other evil, neither is the former meritorious nor the latter to be blamed.” Justin Martyr (Died 165 A.D.) First Apology of Justin

“Again, we affirm that a judgment has been ordained by God according to the merits of every man.” Tertullian On Repentance, Chapter II

IGNATIUS OF ANTIOCH

“Be pleasing to him whose soldiers you are, and whose pay you receive. May none of you be found to be a deserter. Let your baptism be your armament, your faith your helmet, your love your spear, your endurance your full suit of armor. Let your works be as your deposited withholdings, so that you may receive the back-pay which has accrued to you” (Letter to Polycarp 6:2 [A.D. 110]).

JUSTIN MARTYR

“We have learned from the prophets and we hold it as true that punishments and chastisements and good rewards are distributed according to the merit of each man’s actions. Were this not the case, and were all things to happen according to the decree of fate, there would be nothing at all in our power. If fate decrees that this man is to be good and that one wicked, then neither is the former to be praised nor the latter to be blamed” (First Apology 43 [A.D. 151]).

TATIAN THE SYRIAN

“[T]he wicked man is justly punished, having become depraved of himself; and the just man is worthy of praise for his honest deeds, since it was in his free choice that he did not transgress the will of God” (Address to the Greeks 7 [A.D. 170]).

ATHENAGORAS

“And we shall make no mistake in saying, that the [goal] of an intelligent life and rational judgment, is to be occupied uninterruptedly with those objects to which the natural reason is chiefly and primarily adapted, and to delight unceasingly in the contemplation of Him Who Is, and of his decrees, notwithstanding that the majority of men, because they are affected too passionately and too violently by things below, pass through life without attaining this object. For . . . the examination relates to individuals, and the reward or punishment of lives ill or well spent is proportioned to the merit of each” (The Resurrection of the Dead 25 [A.D. 178]).

THEOPHILUS OF ANTIOCH

“He who gave the mouth for speech and formed the ears for hearing and made eyes for seeing will examine everything and will judge justly, granting recompense to each according to merit. To those who seek immortality by the patient exercise of good works [Rom. 2:7], he will give everlasting life, joy, peace, rest, and all good things, which neither eye has seen nor ear has heard, nor has it entered into the heart of man [1 Cor. 2:9]. For the unbelievers and the contemptuous and for those who do not submit to the truth but assent to iniquity . . . there will be wrath and indignation [Rom. 2:8]” (To Autolycus 1:14 [A.D. 181]).

IRENAEUS

“[Paul], an able wrestler, urges us on in the struggle for immortality, so that we may receive a crown and so that we may regard as a precious crown that which we acquire by our own struggle and which does not grow upon us spontaneously. . . . Those things which come to us spontaneously are not loved as much as those which are obtained by anxious care” (Against Heresies 4:37:7 [A.D. 189]).

TERTULLIAN

“Again, we [Christians] affirm that a judgment has been ordained by God according to the merits of every man” (To the Nations 19 [A.D. 195]).

“In former times the Jews enjoyed much of God’s favor, when the fathers of their race were noted for their righteousness and faith. So it was that as a people they flourished greatly, and their kingdom attained to a lofty eminence; and so highly blessed were they, that for their instruction God spoke to them in special revelations, pointing out to them beforehand how they should merit his favor and avoid his displeasure” (Apology 21 [A.D. 197]).

“A good deed has God for its debtor [cf. Prov. 19:17], just as also an evil one; for a judge is the rewarder in every case [cf. Rom. 13:3–4]” (Repentance 2:11 [A.D. 203]).

HIPPOLYTUS

“Standing before [Christ’s] judgment, all of them, men, angels, and demons, crying out in one voice, shall say: ‘Just is your judgment,’ and the justice of that cry will be apparent in the recompense made to each. To those who have done well, everlasting enjoyment shall be given; while to lovers of evil shall be given eternal punishment” (Against the Greeks 3 [A.D. 212]).

CYPRIAN OF CARTHAGE

“The Lord denounces [Christian evildoers], and says, ‘Many shall say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in your name, and in your name have cast out devils, and in your name done many wonderful works? And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from me, you who work iniquity’ [Matt. 7:21–23]. There is need of righteousness, that one may deserve well of God the Judge; we must obey his precepts and warnings, that our merits may receive their reward” (The Unity of the Catholic Church 15, 1st ed. [A.D. 251]).

“[Y]ou who are a matron rich and wealthy, anoint not your eyes with the antimony of the devil, but with the collyrium of Christ, so that you may at last come to see God, when you have merited before God both by your works and by your manner of living” (Works and Almsgivings 14 [A.D. 253]).

LACTANTIUS

“Let every one train himself to righteousness, mold himself to self-restraint, prepare himself for the contest, equip himself for virtue . . . [and] in his uprightness acknowledge the true and only God, may cast away pleasures, by the attractions of which the lofty soul is depressed to the earth, may hold fast innocence, may be of service to as many as possible, may gain for himself incorruptible treasures by good works, that he may be able, with God for his judge, to gain for the merits of his virtue either the crown of faith, or the reward of immortality” (Epitome of the Divine Institutes 73 [A.D. 317]).

CYRIL OF JERUSALEM

“The root of every good work is the hope of the resurrection, for the expectation of a reward nerves the soul to good work. Every laborer is prepared to endure the toils if he looks forward to the reward of these toils” (Catechetical Lectures 18:1 [A.D. 350]).

JEROME

“It is our task, according to our different virtues, to prepare for ourselves different rewards. . . . If we were all going to be equal in heaven it would be useless for us to humble ourselves here in order to have a greater place there. . . . Why should virgins persevere? Why should widows toil? Why should married women be content? Let us all sin, and after we repent we shall be the same as the apostles are!” (Against Jovinian 2:32 [A.D. 393]).

AUGUSTINE

“We are commanded to live righteously, and the reward is set before us of our meriting to live happily in eternity. But who is able to live righteously and do good works unless he has been justified by faith?” (Various Questions to Simplician 1:2:21 [A.D. 396]).

“He bestowed forgiveness; the crown he will pay out. Of forgiveness he is the donor; of the crown, he is the debtor. Why debtor? Did he receive something? . . . The Lord made himself a debtor not by receiving something but by promising something. One does not say to him, ‘Pay for what you received,’ but ‘Pay what you promised’” (Explanations of the Psalms 83:16 [A.D. 405]).

“What merits of his own has the saved to boast of when, if he were dealt with according to his merits, he would be nothing if not damned? Have the just then no merits at all? Of course they do, for they are the just. But they had no merits by which they were made just” (Letters 194:3:6 [A.D. 412]).

“What merit, then, does a man have before grace, by which he might receive grace, when our every good merit is produced in us only by grace and when God, crowning our merits, crowns nothing else but his own gifts to us?” (ibid., 194:5:19).

PROSPER OF AQUITAINE

“Indeed, a man who has been justified, that is, who from impious has been made pious, since he had no antecedent good merit, receives a gift, by which gift he may also acquire merit. Thus, what was begun in him by Christ’s grace can also be augmented by the industry of his free choice, but never in the absence of God’s help, without which no one is able either to progress or to continue in doing good” (Responses on Behalf of Augustine 6 [A.D. 431]).

SECHNALL OF IRELAND

“Hear, all you who love God, the holy merits of Patrick the bishop, a man blessed in Christ; how, for his good deeds, he is likened unto the angels, and, for his perfect life, he is comparable to the apostles” (Hymn in Praise of St. Patrick 1 [A.D. 444]).

COUNCIL OF ORANGE II

“[G]race is preceded by no merits. A reward is due to good works, if they are performed, but grace, which is not due, precedes [good works], that they may be done” (Canons on grace 19 [A.D. 529]).

Love & truth,

Matthew