“Divine wrath is good news. The Gospel is good news, after all, and the Gospel declares divine wrath over and over again. Indeed, the Gospel of Matthew records five long teaching discourses of Jesus, and at the end of each of them, Jesus speaks of the righteous earning an eternal reward and the wicked going off to eternal punishment (see Matt 7:15-29, 10:37-39, 13:44-50, 18:21-35, and 25:31-46). Jesus frequently disputes with Pharisees, Sadducees, chief priests, and scribes, and he does not shy from showing anger at their deeds: “You serpents, you brood of vipers, how can you flee from the judgment of Gehenna?” (Matt 23:33). Jesus further reveals that He will personally come again to judge the living and the dead, promising that He will send “those who have done good deeds to the resurrection of life, but those who have done wicked deeds to the resurrection of condemnation” (John 5:29).

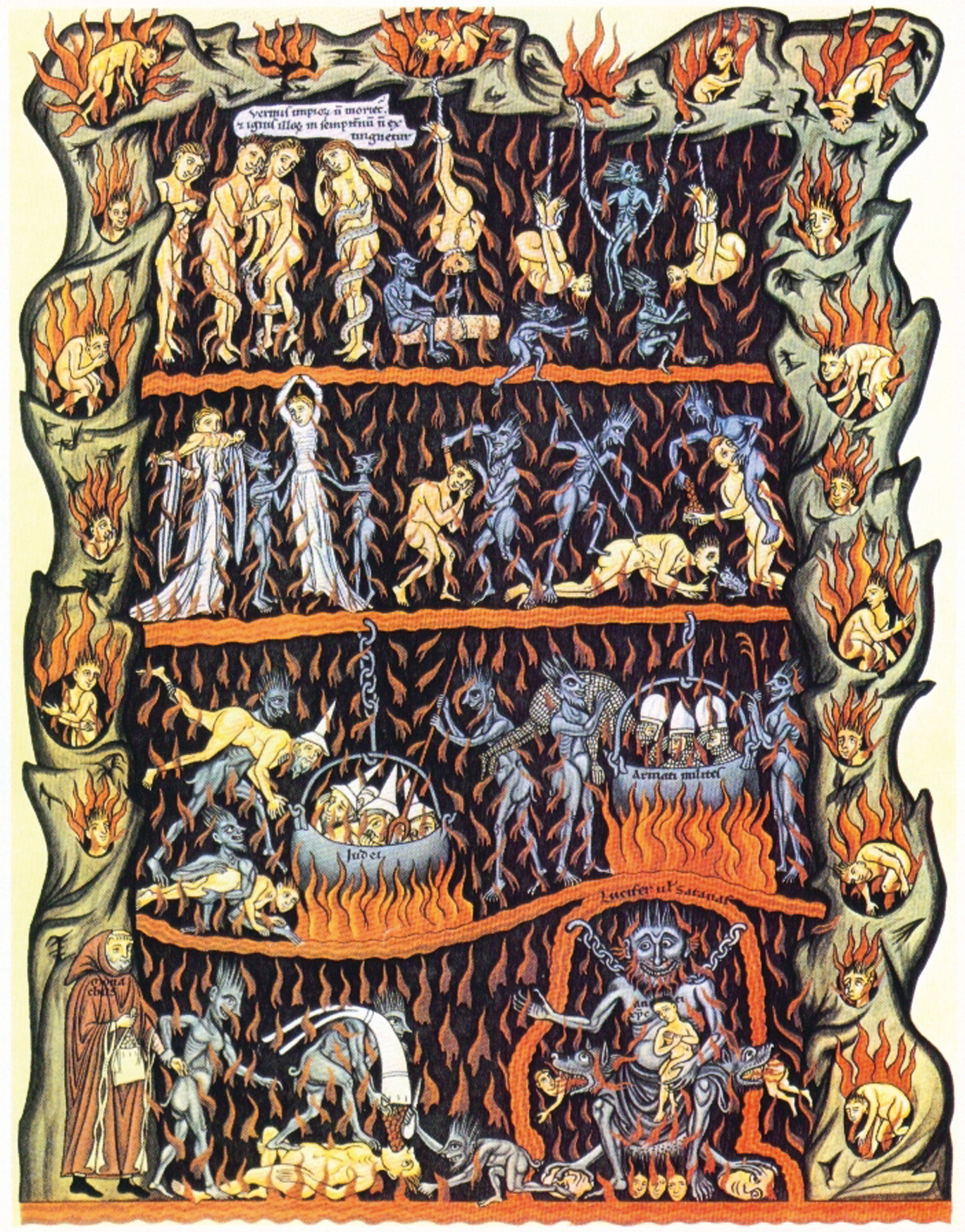

-“Job pointing to the abyss of Hell”, Book of Hours, about 1410, by follower of the Egerton Master (French, / Netherlandish, active about 1405 – 1420), Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink, Leaf: 19.1 × 14 cm (7 1/2 × 5 1/2 in.), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig IX 5, fol. 156v, 83.ML.101.156v, please click on the image for greater detail.

This can be rather surprising. Jesus says that he came that we “might have life and have it more abundantly” (John 10:10). He taught us: “love your enemies, do good to those who hate you” (Luke 6:27). Jesus is rich in mercy, ever delighted to forgive sinners. But the fact that Jesus judges men and condemns some to punishment—even eternal punishment—does not oppose His benevolence to mankind or His mercy. Christ’s judgment is, in fact, a great mercy, for judgment establishes justice in creation.

Injustice marks our world. Men and women murder innocent people, deceive others, and abandon their families and commitments. Yet God does not deign to leave His creation in shambles. He promised to right every wrong, and punishing sin is necessary in that process. It is bad for anyone to profit in any way from doing evil, and God’s punishment takes away all ill-gotten gains. By Christ’s judgment, every murder and assault, every slander and lie, every theft and blasphemy will come to the light and be punished, and no profit from these evils will remain.

Even beyond restoring the order of justice, punishment is a medicine for the greatest spiritual sickness: sin. Sin warps us and taints us. The more we sin, the more we learn to love the evil we do. Jesus hates sin because it ruins the people He loves, corrupting them and deadening them to the divine life He offers. His message of punishment reveals just how ugly and offensive sin actually is. If the God who is all-knowing and all-loving despises sin with such intensity, we ought to hate our sin and our wicked desires. The revelation of divine wrath calls us to a conversion which demands our transformation. In Romans, Saint Paul describes our salvation as a result of justification. By grace, God makes us just. We can truly become worthy of eternal life if we allow God to shatter the sin that gets in the way of that. We should view all God’s punishments in that light, minding what He said long ago: “Do I not rejoice when [the wicked] turn from their evil way and live?” (Ezek 18:23).

Jesus, by His judgment, will establish lasting and perpetual justice, and this is good news indeed. In the Creed and the Te Deum, we even announce rather joyfully that Jesus will come again and be our judge. It is a happy thought since Jesus is not a judge “Who is unable to sympathize with our weakness, but One Who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin” (Heb 4:15). He is a judge Who makes it rather clear how to attain a good verdict and how to find an ally on the bench: “You are my friends if you do what I command you. I no longer call you slaves, because a slave does not know what his master is doing. I have called you friends, because I have told you everything I have heard from My Father” (John 15:14-15). There is no way to heaven but by judgment. By shunning the sin Christ hates and by trusting that He desires to justify us, we can seek his help to attain true conversion. By His grace, we will be made worthy—and thus be judged worthy—of eternal bliss.”

Love, and the infinite wisdom and mercy of His justice. Have mercy on me, O Lord, for I am a sinful man. His justice is a mercy to those aggrieved.

Matthew