-by Joseph Heschmeyer, a former lawyer and seminarian, he blogs at Shameless Popery.

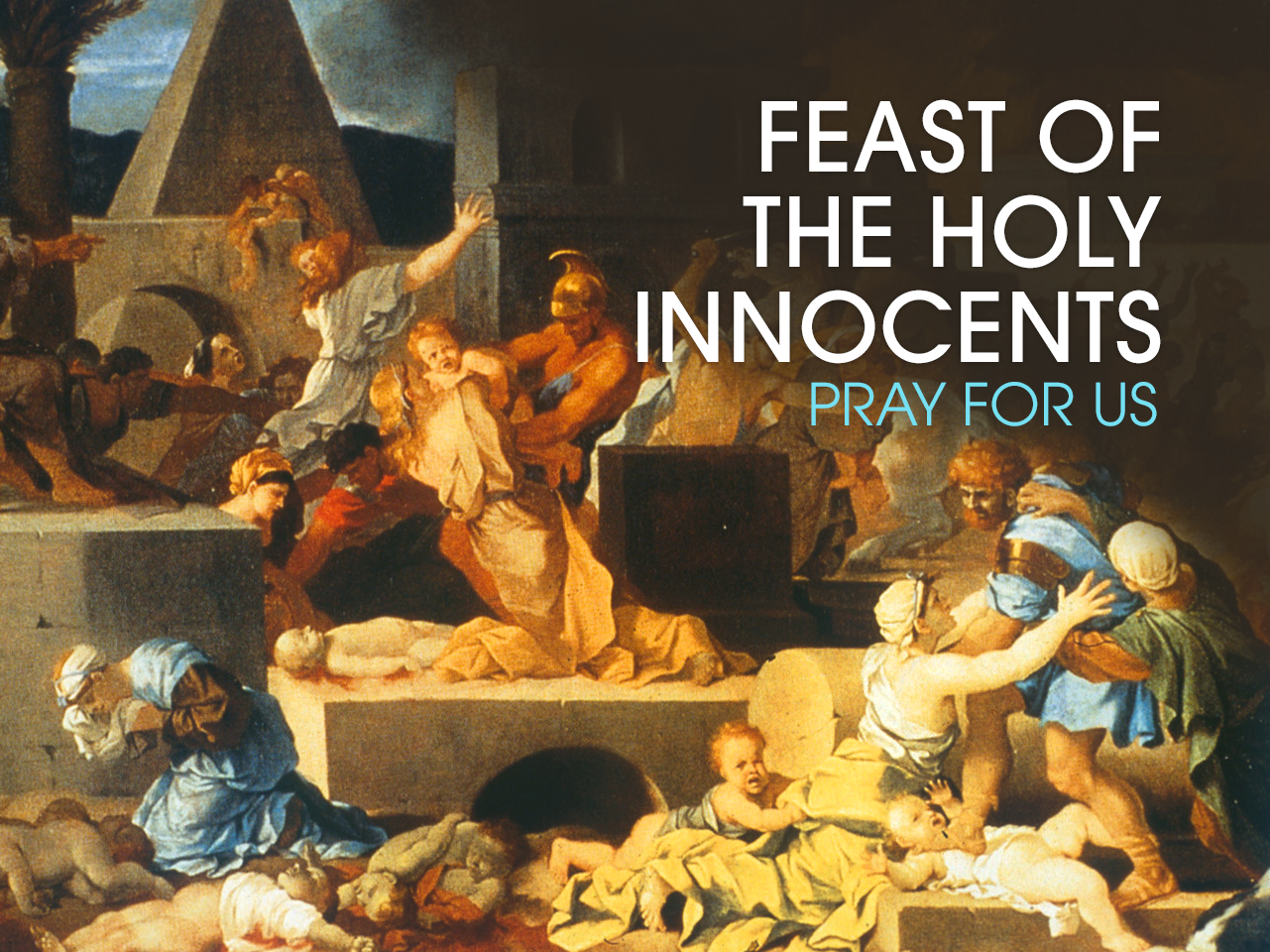

“Today is the Feast of the Holy Innocents, in which we praise as saints and martyrs the children murdered in Jesus’ stead by King Herod, who feared the news of the birth of a rival king.

The biblical basis for this feast is Matthew 2:16, which says that “Herod, when he saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, was in a furious rage, and he sent and killed all the male children in Bethlehem and in all that region who were two years old or under, according to the time which he had ascertained from the wise men.”

Prudentius (348-c. 413) wrote his beautiful Salvete flores Martyrum in their honor, as part of his larger poem in honor of the Feast of the Epiphany. There are various English translations, but I’m fond on this one by Nicholas Richardson:

Hail, all you flowers of martyrdom,

whom, at life’s very door,

Christ’s persecutors slew, as storms

the new-born roses kill!

O tender flock, you are the first

of offerings to Christ:

before his altar, innocent,

with palms and crowns you play.

But do the Holy Innocents deserve to be called saints, much less martyrs? After all, “martyr” means “witness,” and it’s not as if they were voluntarily witnesses who went to their deaths for the sake of Christ. As Charles Péguy observes, the Holy Innocents were “the only Christians assuredly who on Earth had never heard tell of Herod” and “to whom, on Earth, the name of Herod meant nothing at all.” Even calling them “Christians” seems wrong, since they weren’t baptized and knew no more about Jesus than they did about Herod. Right?

Wrong. Jesus speaks of his own death as a kind of baptism, saying during his public ministry, “I have a baptism to be baptized with; and how I am constrained until it is accomplished!” (Luke 12:50). The early Christians picked up on this. Though insisting that baptism is necessary for salvation, Christians like St. Cyprian are clear that “they certainly are not deprived of the sacrament of baptism who are baptized with the most glorious and greatest baptism of blood.”

Similarly, Tertullian describes the blood and water flowing from the pierced side of Christ (John 19:34) as the “two baptisms,” which Jesus gives us “in order that they who believed in his blood might be bathed with the water; they who had been bathed in the water might likewise drink the blood.” He views this “second font,” martyrdom, as “the baptism which both stands in lieu of the fontal bathing when that has not been received, and restores it when lost.” So the early Christians didn’t view martyrdom as an exception to the need to be baptized. Rather, they viewed it as a sort of baptism—in blood instead of water.

So it’s not an exaggeration to say that the Holy Innocents—who died for Christ, and even died in Jesus’ place—were baptized in blood. We can be assured of their salvation, since Jesus promised that “whoever loses his life for My sake, he will save it” (Luke 9:34).

And all this despite their young age. St. Irenaeus, writing c. 180 AD, says that God

suddenly removed those children belonging to the house of David, whose happy lot it was to have been born at that time, that He might send them on before into His kingdom; He, since He was himself an infant, so arranging it that human infants should be martyrs, slain, according to the Scriptures, for the sake of Christ, who was born in Bethlehem of Judah, in the city of David.

This is an important detail: St. Matthew presents the death of these children not simply as a tragedy, but also as a fulfillment of “what was spoken by the prophet Jeremiah” (Jer. 31:15; Matt. 2:16-18). So these infants are martyrs in a unique way, since their death helps to prove that the child Jesus is the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy.

Their death also reveals Christ as the New Moses. Prudentius makes this connection in his poem:

’Mid his coevals’ streams of blood

the Virgin’s child, alone

unharmed, deceived the sword, which robbed

these mothers of their babes.

Thus Moses, savior of his race,

and Christ prefiguring,

did once escape the foolish laws

which evil Pharaoh made.

So there are biblical reasons for understanding the Holy Innocents as martyrs in the sense of “witnesses.” Their death tells us something about Jesus Christ.

Cyprian, writing in the middle of the third century, describes the Holy Innocents not only as martyrs, but as a sort of prototype for all martyrs:

The nativity of Christ witnessed at once the martyrdom of infants, so that they who were two years old and under were slain for His name’s sake. An age not yet fitted for the battle appeared fit for the crown. That it might be manifest that they who are slain for Christ’s sake are innocent, innocent infancy was put to death for His name’s sake. It is shown that none is free from the peril of persecution, when even these accomplished martyrdoms.

By their death, the Holy Innocents also teach us something of the ruthlessness of the Enemy, as well as something about the Christian life—namely, that we’re not promised it will be easy. After all, if even these pure and innocent children should suffer such a fate, why should we expect to be spared hardship or persecution?

But Cyprian also highlights where we tend to go wrong in our thinking about martyrdom. It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking of martyrdom as a kind of good work that the martyr does for Christ. But the early Christians warned against this. The Martyrdom of Polycarp, written within a year of Polycarp’s death in 155, contrasts St. Polycarp’s martyrdom with the failed martyrdom of Quintus, who “forced himself and some others to come forward voluntarily” to trial, in an attempt to be martyred, only to end up apostatizing and offering sacrifice to the pagan gods.

Instead, martyrdom is a grace that—if need be—we receive from Christ. As Cyprian says, “the cause of perishing is to perish for Christ. That Witness Who proves martyrs, and crowns them, suffices for a testimony of His martyrdom.” So it’s not the Holy Innocents who make themselves martyrs. It’s ultimately Christ Who makes them saints and martyrs.

Just as Christ makes saints of babies in water baptism every day, He gave the Holy Innocents the grace of becoming saints and martyrs through the baptism of blood, so that (in Péguy’s words), those “who knew nothing of life and received no wound except that wound which gave them entry into the kingdom of heaven.”

Love & Merry Christmas,

Matthew