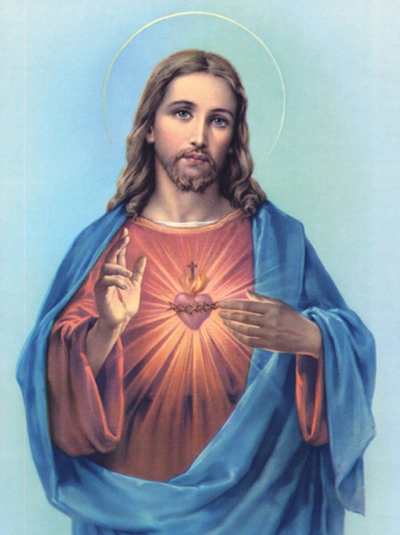

-by Corrado Giaquinto, “Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque Contemplating the Sacred Heart of Jesus,” c. 1765, oil on canvas, 171 cm (67.3 in); width: 123 cm (48.4 in), private collection, please click on the image for greater detail

“O Sacred Heart of Jesus, we place our trust in Thee!” -traditional added at the end of McCormick family grace

-by Dr Kody Cooper

“What is June for? The sixth month’s name derives from the Roman goddess Juno, wife of Jupiter and goddess of marriage and fertility. June was a time for the seeds of new life: sowing crops, weddings, and the beginning of fruitful marriages. In short, June has long been associated with love. And indeed, in the late modern West, we are presented with two rival visions of love to celebrate in June, each with its own sexual ethic and account of the virtues: Pride, which contends “love is love,” and Humility, which proclaims “God is love.”

The denomination of June as a season of “pride” can be traced back to the Stonewall riots in June 1969, which followed upon a police raid of a gay bar. The following June, gay-rights activists organized a commemorative march and demonstration in New York City, and activists adopted the moniker “Gay Pride.” The man who takes credit for coining the term explained his reasoning: “The poison was shame, and the antidote is pride.”

Hence, Pride Month was born of a desire to combat shame within the gay community. This desire can be understood in light of the Christian sexual ethic that had informed American mores to a degree but had already been rejected by many American elites.

In the traditional Christian view, temperance is a cardinal virtue, and shamefacedness is an essential component of it. Temperance considers the pleasures of touch, particularly the pleasures of the table and the bed. The temperate person exercises moderation in these pleasures, avoiding both excess and deficiency. Integral to temperance is shamefacedness, a kind of fear, which is an aversion of desire away from some evil. Shamefacedness is the fear or recoiling from some action that is disgraceful.

The part of temperance that deals with sex is called “chastity,” and it is the virtue by which reason governs sexual desire. The traditional Christian understanding of sexual desire is teleological. It is a gift from God imbued with intrinsic meaning and purpose: to join man and woman in the special bond of marital friendship and that is typically generative of new life. In short, sex was understood to be unitive and procreative such that in the marital act, lovers fully gave of themselves to become “one flesh,” a unity that imaged Trinitarian Love. Chastity therefore meant checking desires for sex that strayed outside of this order, and the chaste person exercised virtue when he recoiled at—was ashamed of—such actions. On this view, heterosexual and non-heterosexual persons alike were required to govern their desires by the virtue of chastity.

While the intellectual and social seeds of the sexual revolution had long been germinating, the 1960s saw the Christian understanding of sex overthrown. In 1964, most American states had laws on the books that restricted access to contraception, for contraception thwarted the teleological purpose of sex. But in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Supreme Court struck down anti-contraception laws as violative of the Constitution, upending the classical Christian natural law logic that such laws presupposed. With the recently invented technology of the birth control pill now widely available, no longer was it presumed that sex was essentially tethered to procreation. Rather, sex became a form of recreation for the expressive self. And this, quite logically, led the gay community to wonder: Why should expressive individualism and recreation be restricted to married heterosexuals?

The promoters of Pride worked out socially and morally what was already implicit in the new legal order. The law is a tutor, and it taught that sex was no longer essentially unitive, procreative, and marital. Why then should homosexual sex be considered shameful? Of course, residual shamefacedness about gay sex remained ingrained in the mores of many Americans. But such attitudes, increasingly cut off from the Christian understanding of the meaning of sex—and the vibrant institutions that embody and sustain that vision—were readily redescribed as “poison.” The antidote was to call for a new virtue: “pride.” Pride functioned as a new sort of fortitude: the habit by which members of the gay community would individually and collectively come out of the closet with confident self-assurance and claim their equal rights in a transformed social order. The older shamefaced attitudes that had been parts of temperance would now increasingly appear as vices: the ignorant prejudice or animus of bigots.

Pride’s popular slogan “love is love” is thus a fitting shorthand for its sexual ethic. Because sex is not inherently a one flesh union of husband and wife, but rather an avenue for self-expression and recreation, no one form of romantic love has any moral superiority over any other. They are all equally “love” and therefore should be treated with absolute moral, social, and legal equality.

The contrasting vision of Christian Humility is “God is Love.” It is antithetical to love as conceived by expressive individualism because Love Itself calls the beloved not to self-expression, but to humble obedience—that is, to make a gift of oneself as an abode for Him to reign in our hearts (John 14:23-24). The Church proclaims this message to the world in the month of June in a special way that is deeply intertwined with the story of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, the beloved disciple of Christ’s Sacred Heart.

Born on July 22, 1647 in France, Margaret Mary was still very young when she consecrated herself to God: “O my God, I consecrate to Thee my purity, and I make Thee a vow of perpetual chastity.” In offering up her sexuality as a gift to God, she was given the lifelong gift of chastity and an accompanying “horror” of “anything against purity”—and provided an example of holiness particularly relevant to all whose vocation is not to marriage.

Her Divine Suitor eventually directed her to join the Visitandines. Already extremely advanced in the spiritual life—she had had several visions of Our Lady and Our Lord—obedience was an ongoing drama. Our Lord asked of her various prayers, sacrifices, and penances, but they sometimes conflicted with the commands of her superiors. When the saint beseeched Christ for help, he replied to her that she should do nothing of what he had commanded her without her superiors’ consent: “I love obedience, and without it no one can please Me.”

Humble obedience and the sacrifice of the desires of the self are thematic in St. Margaret Mary’s life. She struggled interiorly to heed Christ’s commands and acknowledged her weakness and inability to do what He asked without His aid. She had entered the convent on one condition: that she could never be forced to eat cheese, to which she was extremely averse. When her Sovereign Master asked her to eat cheese at a meal, she resisted for three days, until in answer to her prayer the Lord said: “There must be no reserve in Love.” She ate the cheese, and recalled that “I never in my life felt so great a repugnance to anything.” Indeed, to conform her more perfectly to himself, Christ identified all that was most opposed to her predilections, and increasingly required her to act contrary to them.

This and many other sufferings conformed her to the crucified Christ and were the essential preconditions to the revelation of His Sacred Heart, which involved such ecstatic spiritual delights that she could not describe them. Christ revealed His Heart to be as a mighty furnace, a throne of flames shining like the sun, encircled by a crown of thorns with the Cross seated upon it. The saint was asked to honor His Sacred Heart with a feast day that would fall in June, in order to manifest to mankind anew His infinite love for them. This would ultimately be fulfilled two hundred years after St. Margaret Mary’s death, when Pope Leo XIII raised the feast to a Solemnity in 1889.

Christ’s Sacred Heart—as both His literal heart of flesh and the self-sacrificial gift of himself for the world that it symbolizes—burns with a love of charity by which he has a just claim on our hearts, on the obedience of our wills. Its radiant brilliance reminds us that God’s love radically extends to all persons, regardless of any predilections they might have that do not conform to His will. It is only through our free choice to nail the desires of the self upon the Cross that His Sacred Heart is permitted to be enthroned in each of our own.

While the contrasts of Humility’s vision with Pride’s are apparent, we should note that, for many, the celebration of Pride Month can be well intentioned. The desire to show compassion, as well as to be acknowledged, recognized, and affirmed, are healthy in their root because they stem from the fundamental human desire to be loved and cared for. Pride’s vision of love is fundamentally flawed, but not because persons who do not identify as heterosexual are of any lesser dignity. From the traditional Christian perspective, it is flawed in as much as it was built upon a rejection of the moral order that God established and the refusal of humble obedience to and reliance upon the One who sacrificed Himself to help us fulfill it. Pride’s vision of love must end in disappointment. For by His Sacred Heart, Jesus loves each of us infinitely more than any creature could, including ourselves. It is humbling to admit that we are not sufficient unto ourselves to love. But our Divine Lover promises a joy beyond anything worldly love promises, if only we will offer ourselves as gifts to Him, and allow Him to transform us into the beautiful creatures we were created to be.”

For the love of God and willing the good of others,

Matthew