please click on the image for greater detail

“Presentism” is a heresy of history of reading history through modern point of view, culture, and biases. We cannot judge the past from the present. It is impossible. Nor would the past understand the present. The best way to read history is to prepare like an actor to participate in that moment in history taking a well know, well worn role, and seeing it through those eyes.

-by Christopher Check

“Events in history happen in certain times and places. Goes without saying, right? I’m not so sure. It’s not uncommon for us to examine the past through the lenses of today.

I once read a history of the eleventh-century Norman conquest of Sicily. This otherwise lively and accurate account portrayed Robert Guiscard and Roger de Hauteville as venture capitalists, a profession that no medieval man could have wrapped his imagination around.

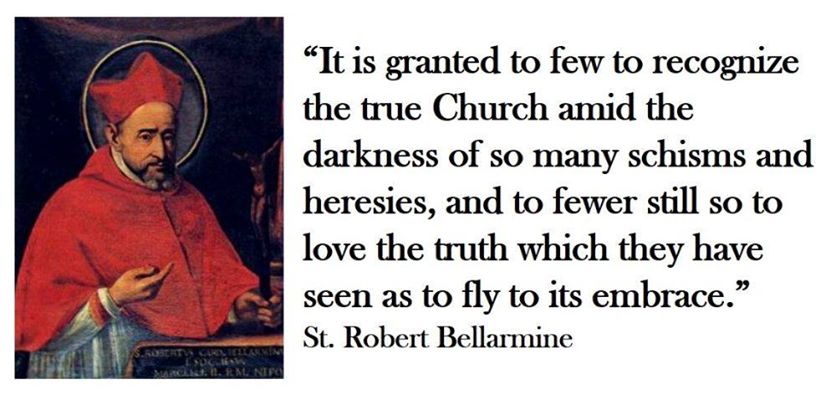

It is a mistake to judge the decisions and actions of the churchmen involved in what has come to be called the Galileo Affair through the lens (no pun intended here) of modern astronomical discoveries. Better to consider the event by taking a stab at understanding the state of the science at the time, the personality of Galileo, the cultural and religious atmosphere, and the personality of the one saint in the story, the man whose sanctity we celebrate today on his feast day: Robert Cardinal Bellarmine.

-Nikolaus Kopernikus, “Torun portrait” (anonymous, c. 1580), kept in Toruń town hall, Poland, please click on the image for greater detail

Copernicus raises a question

Since ancient times man’s understanding of the cosmos was geocentric: a fixed, immobile Earth around which the heavenly bodies orbited. Aristotle and Ptolemy, whose model included planetary epicycles to account for apparent retrograde motion, were the chief proponents of this model. Among the ancients there was at least one proponent of a heliocentric model, Aristarchus of Samos (known to us through Archimedes), but in the absence of observational evidence the model that was intuitive took hold. Geocentrism was not doctrine, but because it came from Aristotle and because it comported with Scripture, the Church adopted the model.

Not until a canon of the Catholic Church, Nicholas Copernicus, in 1543 published on his deathbed his De revolutionibus orbium ceolestium did anyone give a serious look at a heliocentric model. Even then, few took notice, and the Church certainly was not alarmed. Fact is, Copernicus was encouraged by priests to publish, and he dedicated the book to Pope Paul III. (Luther and Calvin, it’s worth noting, were in fits; Luther called Copernicus a “fool.”)

Copernicus had not one piece of physical observational evidence in support of heliocentrism. De revolutionibus was a complex collection of mathematical formulas and Latin descriptions written to predict the location of the heavenly bodies throughout the year. It’s important to underscore that astronomers at this time in history were not natural philosophers, what we call “physicists” today. They were mathematicians. Their job was to devise the formulas that predicted the location of the heavenly bodies, whether or not the formulas were a true account of what was happening in the physical cosmos.

“Why bother then?” Well, if you were the navigator on a seagoing vessel, or one of the Jesuits at the Roman College hard at work on bringing more precision to the Julian Calendar (some eleven minutes too long every year), where the planets and stars were and when was of central importance to your trade. Also, if you were an astrologer—and make no mistake, back then astrology and astronomy were considerably less delineated than they are now (Galileo wrote horoscopes for cash)—the position of the heavenly bodies was critical to your trade, too.

-Galileo Galilei (1636), by Justus Sustermans, please click on the image for greater detail

Galileo: a force of nature

Knowing the distinction between astronomers (mathematicians) and natural philosophers (physicists) helps us appreciate just how groundbreaking Galileo was: he looked at astronomical questions from the perspective of a natural philosopher. His interests were motion, dynamics, mechanics, etc.; in other words, the fields that tell us what is happening in the physical world.

His theories would not have received the attention they did had it not been for the arrival in the early seventeenth century—in the Netherlands, perhaps—of a carnival toy. Galileo did not invent the telescope, but he sure did improve it, and—another critical contribution—in December of 1609 he pointed it at the heavens. The subsequent months revealed undiscovered wonders, the “mountains of the moon,” the moons of Jupiter, the phases of Venus. None of these was proof of a heliocentric solar system, but for a pioneer of deductive reasoning, they constituted compelling evidence.

Equally compelling was the force of Galileo’s personality. An impatient genius, Galileo did not go out of his way to make friends among his academic colleagues in Pisa, Florence, Padua, and Rome. His correspondence is replete with bold expressions of his arrogance and bitter insults leveled at men who disagreed with him. He not only lacked humility, he took pleasure at social gatherings in humiliating other scholars with rhetorical traps. His obstinacy is something to marvel at, especially when he was wrong—as he was about the tides, circular orbits, and comets, for example.

Had Galileo been a little more sensitive to the religious atmosphere of his age, the story might have gone less badly. It is commonly believed that the Church’s leading minds refused to look at Galileo’s arguments or look through his telescope. Nothing could be further from the truth. He had the backing of the Carmelite scientist and philosopher Paolo Antonio Foscarini and of many the Jesuits at the Roman College, including Gregorian Calendar architect Christopher Clavius, who were buying up his telescopes and confirming his findings. (His chief academic adversaries were laymen.)

It is true, however, that Galileo made his discoveries in a world still reacting to Martin Luther’s and John Calvin’s insistence that Scripture was subject to personal interpretation. The Council of Trent in the mid-sixteenth century said it was not. There was no shortage of scriptural passages making reference to a fixed Earth orbited by sun and stars. (There still are!) The Church, as Cardinal Bellarmine was at pains to explain to Galileo when they met in 1616, needed to be deliberate in interpreting scriptural passages that seemed to contradict the discoveries of modern astronomy.

Bellarmine: the voice of reason

Bellarmine counseled caution for two reasons. The first showed a more disciplined and careful approach to deductive science than Galileo’s. “The Copernican system predicts the phases of Venus,” Bellarmine told Galileo. “This does not prove the converse, that is: Venus exhibits phases, therefore the universe is Copernican.” Bellarmine was right, of course. Tycho Brahe’s hybrid model, in which all but the Earth revolves around the sun and all that swirling bundle revolves around the Earth, would also account for the phases of Venus. In other words, absent proof (and that does not come until the mid-nineteenth century) caution more than anything was required in reinterpreting Scripture—which brings us to the good saint’s second reason for caution.

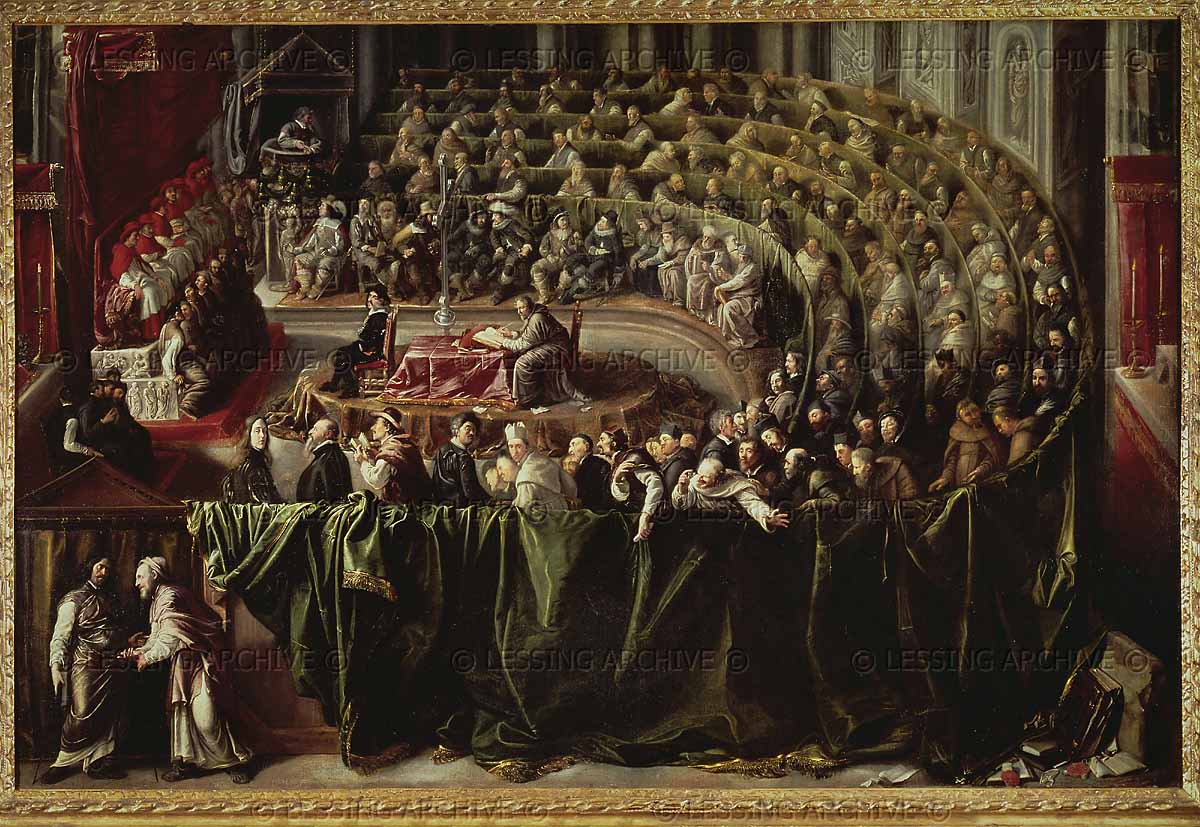

Bellarmine was sharp of mind and had a strong pastoral sense. He told Galileo, “The evidence is insufficient to force scriptural reinterpretations that could lead to doubts in the minds of the faithful about the inerrancy of Scripture.” The position is a perfectly reasonable one. It applies a pastoral solution to a speculative problem. Had Galileo listened to Bellarmine, he would not have found himself in front of an understandably impatient (by this time he had implied that the pope was simpleminded) and admittedly heavy-handed inquisition in 1633.

The dictate of charity

The details of that conflict are for another piece. Let’s conclude with the reflections of Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman, who, while still an Anglican, argued that Bellarmine in his caution was following the dictates of charity:

Galileo might be right in his conclusion that the earth moves; to consider him a heretic might have been wrong; but there was nothing wrong in censuring abrupt, startling, unsettling, unverified disclosures, if such they were, disclosures at once uncalled for and inopportune, at a time when the limits of revealed truth had not as yet been ascertained. A man ought to be very sure of what he is saying, before he risks the chance of contradicting the word of God. It was safe, not dishonest, to be slow in accepting what nevertheless turned out to be true. Here is an instance in which the Church obliges Scripture expositors, at a given time or place, to be tender of the popular religious sense.

I have been led to take a second view of this matter. That jealousy of originality in the matter of religion, which is the instinct of piety, is, in the case of questions that excite the popular mind, also the dictate of charity. Galileo’s truth is said to have shocked and scared the Italy of his day. To say that the Earth went round the sun revolutionized the received system of belief as regards heaven, purgatory, and hell; and it forcibly imposed a figurative interpretation upon categorical statements of Scripture.

Heaven was no longer above and Earth below; the heavens no longer literally opened and shut; purgatory and hell were not for certain under the earth. The catalogue of theological truths was seriously curtailed. Whither did our Lord go on his ascension? If there is to be a plurality of worlds, what is the special importance of this one? And is the whole, visible universe, with its infinite spaces, one day to pass away?

We are used to these questions now and reconciled to them; and on that account are no fit judges of the disorder and dismay that the Galilean hypothesis would cause to good Catholics, as far as they became cognizant of it, or how necessary it was in charity, especially then, to delay the formal reception of a new interpretation of Scripture, till their imaginations should gradually get accustomed to it.”

Love,

Matthew