-by Ali ibn Hassan

“The nature of marriage has been a subject of much discussion and debate over the last couple of decades. Receiving somewhat less attention are the differences among religions over marriage, particularly the differences between Islam and Christianity. In many respects, Islam and Christianity share a common view of the importance of marriage, but there are some significant differences that all Christians should understand.

The Catholic faith teaches that marriage is an unbreakable bond between a man and a woman. The foundations for this understanding can be found in both the Old and New Testaments:

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth.” . . . Therefore, a man shall leave his father and his mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall become one flesh (Gen. 1:27-28, 2:24).

Husbands should love their wives as their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. For no one ever hates his own flesh, but nourishes and cherishes it, just as Christ does the church (Eph. 5:28-33).

The Catechism builds upon God’s call to this fruitful, loved-filled, and unbreakable bond:

The matrimonial covenant, by which a man and a woman establish between themselves a partnership of the whole of life, is by its nature ordered toward the good of the spouses and the procreation and education of offspring; this covenant between baptized persons has been raised by Christ the Lord to the dignity of a sacrament (1601).

Holy Scripture affirms that man and woman were created for one another: “It is not good that the man should be alone.” The woman, “flesh of his flesh,” his equal, his nearest in all things, is given to him by God as a “helpmate”; she thus represents God, from whom comes our help (CCC 1605a).

To Catholics, marriage between baptized persons is a sacrament, which has the meaning of oath or covenant. This covenant bond is a lifelong exchange of persons with God as witness. This exchange forms the basis for a community of love that reflects the sacrificial and holy love God has for his people and is ordered for the good of the man and woman and toward the begetting and education of children. We heed Christ’s words—“Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate” (Mark 10:9)—so, after a baptized couple consummates a validly contracted marriage, it is impossible to break that union except by death. (Non-sacramental marriages, where one or both spouses are unbaptized, are also ordinarily indissoluble except in certain rare cases.)

Like Christianity, Islam values marriage as an important institution for the building of family and society and an integral part of salvation. Various hadiths (traditional religious sayings) bear this out. For example: “There is no foundation that has been built in Islam more loved by Allah . . . than marriage. . . . Allah loves no permissible like marriage, and Allah hates no permissible like divorce” (Mustadrak al-Wasa’il). “Whoever gets married has safeguarded half of his religion” (Wasa’il al-Shia).

The Quran and tradition give further guidance and reasons to marry:

And marry off the single among you and among the righteous of your male and female slaves. If they are poor then Allah will supply their needs from his generosity. And Allah is expansive, knowing. And let those who do not find marriage hold back until Allah grants them of his generosity (Quran 24:32-33).

O young people! Whoever among you can marry, should marry, because it helps him lower his gaze and guard his modesty, and whoever is not able to marry, should fast, as fasting diminishes his sexual desire” (Sahih al-Bukhari).

Whoever chooses to follow my tradition must get married and produce offspring through marriage (and increase the population of Muslims), so that on the Day of Resurrection, I shall confront other Ummah (nations) with the (great) numbers of my Ummah (Wasa’il al-Shia).

Marriage is so important within Islam that no other option is recognized as praiseworthy. Unlike Catholics, who view celibacy for the sake of the kingdom as a high calling, Muslims see the permanent celibate life as unnatural, given men’s sexual needs and the community’s need to grow. Muslims are encouraged to marry early in life in order to avoid forbidden sexual relations (known as zina).

The Arabic word most often associated with marriage is nikah, which means “contract.” A widely quoted definition from influential Salafi cleric Ibn ‘Uthaimin states that marriage is “a mutual contract between a man and a woman whose goal is for each to enjoy the other, become a pious family and a sound society.”

Now, a contract is a promise regarding an exchange of goods. A Muslim marital contract is brokered between two men—the husband-to-be and a representative for the wife-to-be. The contract stipulates the exchange of a mahr, or “bride price,” in exchange for the woman’s hand. It dictates that married life be conducted in accordance with the Quran and requires consent by the woman and two witnesses.

The first and most common category of marriage is the nikah between one man and one woman. A second category, though, is called a nikah mut’ah, or temporary marriage. This type of “marriage” is common in Shia Islam and is designed to make otherwise illicit sexual acts licit by a short-term legal arrangement. Although most Sunni Muslims reject nikah mut’ah, they accept nikah misyar, in which both prospective husband and wife agree to give up certain normal marital rights, like living together, equality between wives, rights to income, and rights of homekeeping, in order to be married. This can be understood as a middle ground between a nikah and a nikah mut’ah.

In addition to these different types of marriage, in Islam, one man can have multiple wives and contract several different types of marriages at the same time. “And if you fear that you will not deal justly with the orphan girls, then marry those that please you of [other] women, two or three or four” (Quran 4:3). This verse and others like it condone polygynous relationships (between one man and multiple women—but not one woman and multiple men). Men are allowed to marry up to four women, provided that they can treat them all equally (see Quran 4:129).

Classically, Muslim men were also allowed to conduct sexual relations with their female slaves, a practice that was brought back recently by ISIS and is found in the Quran: “And they who guard their private parts except from their wives and those their right hands possess [concubines] . . . they will not be blamed” (23:6).

Divorce by either party is allowable within Islam, though it is discouraged. “And when you divorce women and they fulfil their term [of their ‘Iddah, or post-divorce waiting period], either keep them according to reasonable terms or release them according to reasonable terms, and do not keep them, intending harm, to transgress [against them]” (Quran 2:231).

If either party violates the conditions of the signed marital contract or if they have irreconcilable differences, they can obtain a wide variety of types of divorces: from khul’ (mutual contractual divorce initiated by the wife) to talaq (a variety of simple ways for the husband to repudiate the wife, usually requiring a waiting period before the divorce is finalized) to three different types of divorce oaths and finally judicial divorce. Historically, this last right was given to men only, but recently, in some places, women have been given the right to divorce as well.

So although from a distance Christian and Muslim marriages may look a lot alike, there are major differences. Marital contracts within Islam elevate marriage above the mundane while allowing for the reality of man’s frailty, but Islam’s allowance for multiple wives, temporary sexual arrangements, and partial forms of marriage expose a baser contractual view of marriage that falls far short of God’s plan for lifelong covenantal relationships.”

-by Mostafa Ghandar

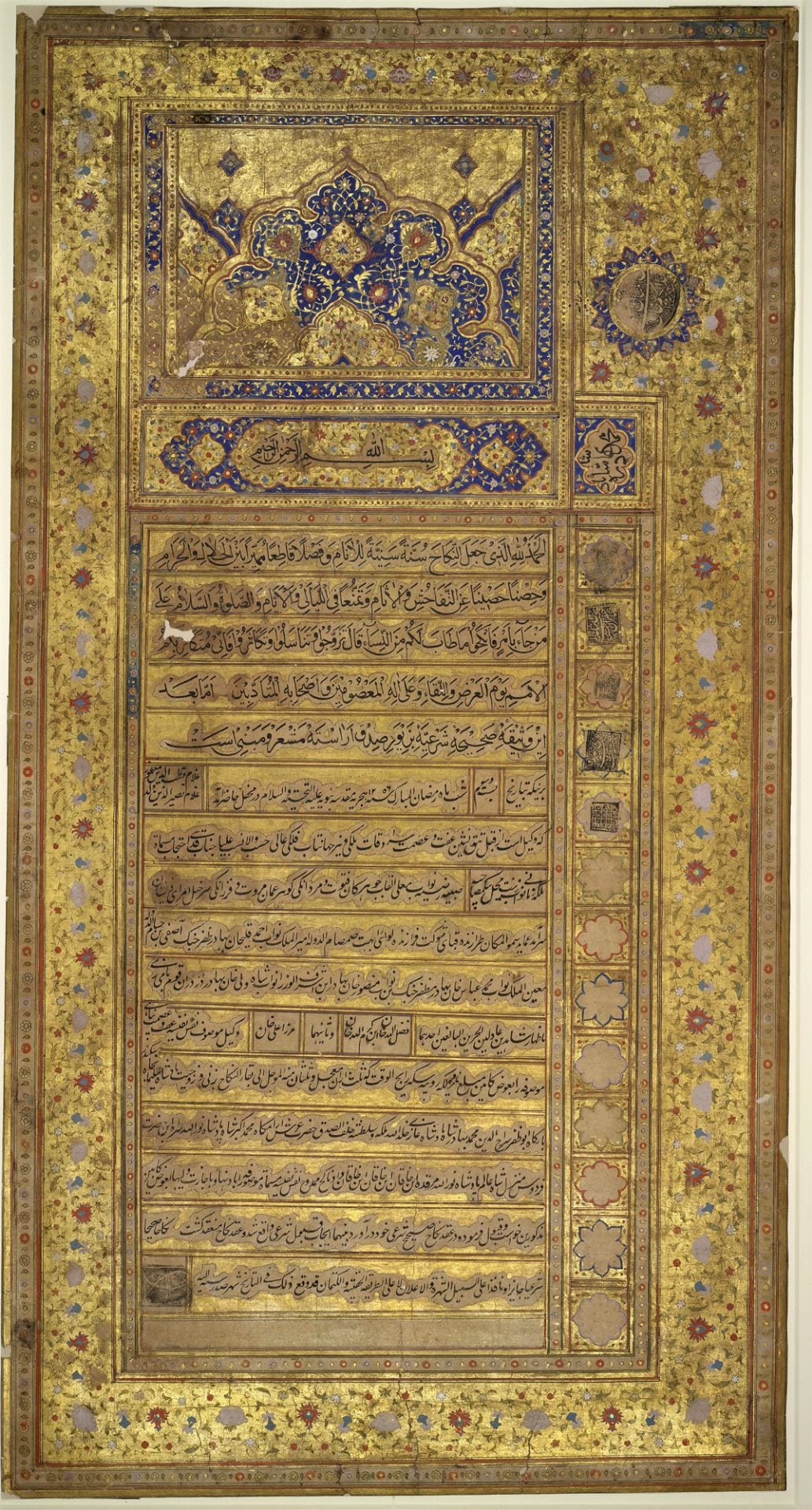

-Islamic marriage contract, please click on the image for greater detail

“Marriage in Islam

The institution of marriage and family is pivotal in Middle East societies, both ancient and modern; perhaps the biblical genealogy of the Old Testament is an indication of this fact. Marriage practices, customs and traditions evolved throughout many thousands of years in this central part of the ancient world.

When the Divine Message of Islam was revealed in the sixth century AD, it was a revolutionary reformation of all aspects of human life: economic, social, and political, and of course religious. Among these was the reformation of marriage practices that prevailed in the pre-Islamic times or ages of ignorance (Al-Gahiliah). These reformations included: limiting the number of wives a man can marry to only four after it was unlimited; allowing women to carry their own family name, and have their financial independence, because they were allowed to trade in their own name and maintain their wealth separate from the husband.

Perhaps marriage in Islam is best described in the following two verses from the Holy Quran, the words of the All Mighty:

وَمِنْ آيَاتِهِ أَنْ خَلَقَ لَكُم مِّنْ أَنفُسِكُمْ أَزْوَاجًا لِّتَسْكُنُوا إِلَيْهَا وَجَعَلَ بَيْنَكُم مَّوَدَّةً وَرَحْمَةً إِنَّ فِي ذَلِكَ لَآيَاتٍ لِّقَوْمٍ يَتَفَكَّرُونَ. ( الروم 21 )

“And among His signs is this, that He created for you mates from among yourselves that you may dwell in tranquility with them, and He has put love and mercy between your hearts. Undoubtedly in these are signs for those who reflect.” (30:21)

وَاللّهُ جَعَلَ لَكُم مِّنْ أَنفُسِكُمْ أَزْوَاجًا وَجَعَلَ لَكُم مِّنْ أَزْوَاجِكُم بَنِينَ وَحَفَدَةً وَرَزَقَكُم مِّنَ الطَّيِّبَاتِ أَفَبِالْبَاطِلِ يُؤْمِنُون وَبِنِعْمَتِ اللّهِ هُمْ يَكْفُرُونَ. (النحل 71 )

“And Allah has made for you wives of your own kind, and has made for you, from your wives, sons and grandsons, and has bestowed on you good provision. Do they then believe in false deities and deny the Favors of Allah” (by not worshipping Allah Alone). An Nahl, 72

Please note the emphasis in the first verse on love and mercy, and on the family in the second verse. This in itself was an important reformation, indicating the necessity of Divine guidance as to the very basic elements of successful marriage, and successful human love, and the family.

Islamic marriage laws together with the inheritance laws regulate the relationships in the basic unit of the human society, the family, in a manner that promotes fairness and dignity, as well as the emotional needs of both the woman and the man and all members of the extended family: in-laws and siblings. So Marriage laws in Islam, while they regulate the relation between men and women in a perfect balance, also foster the preservation and welfare of a healthy relationship in the immediate and the extended family, and in society as a whole.

In Islam, marriages are not considered to be ‘made in heaven’ between ‘soul-mates’ destined for each other; they are not sacraments. They are social contracts which bring rights and obligations to both parties, and can only be successful when these are mutually respected and cherished.

It is interesting to note that in most western countries including Australia modern marriage laws adopted the principles of the Islamic Marriages as a social contracts and departed from the 13th century ideas of marriage as sacraments. In fact the system of marriages registration and marriage celebrants was developed in the ninth century Egypt by the Fatimid’s.

Islamic Contract of Marriage:

In Islam marriage is a formal agreement or a contract (Aqqd Azwag, Aqqed Alqran or Nikah) between a woman and a man, which creates the marital relationship. A marriage contract has a number of essential conditions, and also it can include special conditions that the two parties may wish to include and agree upon.

The Prophet (SAW) said that marriage is the most favored institution by Allah (SWT). As such it is the most important agreement a Muslim will enter into in his life.

The formal conditions or requirements for a valid marriage are as follows:

- The Offer and Acceptance (Al Ijaab Wa Qboul):

1.1. The essential requirement of the contract is the Offering and Acceptance known as Ijaab and Qabool. These statements verify the mutual agreement of the parties concerned and create the marriage relationship.

1.2. The Ijaab and qabool should be stated in clear, well defined words, in one and the same sitting, and in the presence of the witnesses. The person conducting the ceremony may help the two parties to say the offering and accepting words.

1.3. Ijaab and Qabool should be in a language understood by both parties. Qabool should be in the past tense to indicate that acceptance has actually happened and has been completed.

1.4. While documenting the marriage contract is not a requirement, yet it is important to document it for future reference and to preserve the rights of the husband and wife.

- Eligibility of Bride and Groom:

2.1. The groom must be a chaste Muslim having attained the age of puberty. He must not be related to the bride by any of the permanently prohibiting blood, breast feeding, or marital relationships, such as his sisters, paternal and maternal aunts, daughters, grand daughters and others.

2.2. He must not be prohibited from marrying the bride for any of the temporary reasons stipulated in the Quran and Sunnah. For example if a man has four wives, then all other women become temporarily prohibited from him. Another example of a temporary reason is that as long as a man is married to a particular woman, all of her sisters become temporarily prohibited for him.

2.3. The requirement a bride must fulfill is that she must be a chaste Muslim, Christian or Jew. She must not be married to another man, and must not be related to the groom by any of the permanently prohibiting blood, breast feeding, or marital relationships in addition to not being prohibited from marrying the groom for any of the temporary reasons.

- Bride’s Permission and Consent:

3.1. Without the bride’s permission, the contract of marriage is null and void, or may be invalidated by the Islamic authorities at the bride’s request.

3.2. The minimum required permission may be done by either voicing her approval or through a passive expression such as remaining silent when asked about a potential husband and simply nodding her head, or making any other motion to indicate that she does not object to the marriage.

3.3. The Prophet (S.A.W) said: “A deflowered unmarried woman (i.e. widow or divorcee) may not be married without her expressed approval; and a virgin may not be married without her permission, and her silence indicates her consent.” (Bukhari & Muslim)

- The Woman’s Wali (Male Guardian):

4.1. The next requirement for a valid contract of Marriage is for the protection of the woman’s rights, and that is the approval of the woman’s guardian known as the wali. The Messenger of Allah (SAW) said: “A marriage (contract) is not valid without a wali.” (Abu Dawud, At-Tirmidhi)

4.2. Normally, a woman’s wali is her father. If, for any reason, her father is unable to act, her wali would then be her next closest blood relation: the grandfather, uncle, brother, son and so on. The guardian or wali should ascertain the suitability and capability of the prospective husband and review any special conditions and make sure that the bride understands and agrees to it.

4.3. If the bride does not have a Muslim blood-relative as a wali, the Islamic authority, represented by the ruler or judge, would appoint a wali for her. In non-Muslim communities the local Muslim Minister of Religion (Imam) or an elder Muslim can act as the wali of a woman, with her consent.

- The witnesses:

5.1. Another requirement for the validity of a marriage contract is the presence of at least two trustworthy Muslim male witnesses. The Messenger of Allah (SAW) said: “A marriage is not valid without a wali and two trustworthy witnesses”. (Ahmad, Ibn Hibbaan, and others, Authentic according to al-Albaani)

- The Mahr (Dowry):

6.1. The mahr or Sadaqq (Dowry) is a gift given by the man to the woman, on the occasion of the marriage. Allah (SWT) said:

“وَآتُواْ النَّسَاء صَدُقَاتِهِنَّ نِحْلَةً فَإِن طِبْنَ لَكُمْ عَن شَيْءٍ مِّنْهُ نَفْسًا فَكُلُوهُ هَنِيئًا مَّرِيئًا“

And give to the women (whom you marry) their Mahr (obligatory bridal money given by the husband to his wife at the time of marriage) with a good heart, but if they, of their own good pleasure, remit any part of it to you, take it, and enjoy it without fear of any blame (as Allah has made it lawful). (an-Nisaa, 4)

6.2. Allah (SWT) also made a commandment regarding this by saying:

فَمَا اسْتَمْتَعْتُم بِهِ مِنْهُنَّ فَآتُوهُنَّ أُجُورَهُنَّ فَرِيضَةً وَلاَ جُنَاحَ عَلَيْكُمْ فِيمَا تَرَاضَيْتُم بِهِ مِن بَعْدِ الْفَرِيضَةِ إِنَّ اللّهَ كَانَ عَلِيمًا حَكِيمًا

6.3. “… so with those with whom you have enjoyed sexual relations, give them their Mahr as prescribed; but if after a Mahr is prescribed, you agree mutually (to give more), there is no sin on you. Surely, Allah is Ever All-Knowing, All Wise”(An-Nisaa, 24).

- Other Conditions:

7.1. At the time of the marriage contracting, either the bride or the groom may wish to set conditions whose violation would invalidate the contract. This is acceptable as long as the conditions do not violate any Islamic principles. An example of a condition may be that a woman stipulates that she remain in a particular homeland or country during their marriage, or that the wife may have the right to terminate the marriage by divorcing her husband.”

Love & truth,

Matthew