(n.b. in the 2004 Martyrologium Romanum, St Dymphna’s feast day was moved to May 30.)

Dymphna was the only child of a pagan king who is believed to have ruled a section of Ireland in the 7th century. She was the very picture of her attractive young Christian mother.

When the queen died at a very young age, the royal widower’s heart remained beyond reach of comfort. His moody silences pushed him on the verge of mental collapse. His courtiers suggested he consider a second marriage. The king agreed on condition that his new bride should look exactly like his former one.

His envoys went far a field in search of the woman he desired. The quest proved fruitless. Then one of them had a brilliant idea: Why shouldn’t the king marry his daughter, the living likeness of her mother?

Repelled at first, the king then agreed. He broached the topic to his daughter. Dymphna, appalled, stood firm as a rock. “Definitely not.” By the advice of St. Gerebern, her confessor, she eventually fled from home to avoid the danger of her refusal.

A group of four set out across the sea – Father Gerebern, Dymphna, the court jester and his wife. On landing at Antwerp, on the coast of Belgium, they looked around for a residence. In the little village of Gheel, they settled near a shrine dedicated to St. Martin of Tours.

Then spies from her native land arrived in Gheel and paid their inn fees with coins similar to those Dymphna had often handed to the innkeeper. Unaware that the men were spies, he innocently revealed to them where she lived.

The king came at once to Gheel for the final, tragic encounter. Despite his inner fury, he managed to control his anger. Again he coaxed, pleased, made glowing promises of money and prestige. When this approach failed, he tried threats and insults; but these too left Dymphna unmoved. She would rather die than break the vow of virginity she had made with her confessor’s approval.

In his fury, the king ordered his men to kill Father Gerebern and Dymphna. They killed the priest but could not harm the young princess.

The king then leaped from his seat and with his own weapon cut off his daughter’s head. Dymphna fell at his feet. Thus Dymphna, barely aged fifteen, died. Her name appears in the Roman Martyrology, together with St. Gerebern’s on May 15.

In the town of Gheel, in the Flemish-speaking region of Belgium, great honor is paid to St. Dymphna, whose body is preserved in a silver reliquary in the church which bears her name. Gheel has long been known as a place of pilgrimage for persons seeking relief of nervous or emotional distresses. In our century, the name of St. Dymphna as the heavenly intercessor for such benefits is increasingly venerated in America.

-“The Beheading of St Dymphna”, by Godfried Maes, 1688, oil on canvas, Height: 337 cm (132.7 in). Width: 225.5 cm (88.8 in), Saint Dymphna Church, Geel, Belgium, please click on the image for greater detail

-from an article by Michael J. Lichens, a convert from Evangelical Protestantism to Roman Catholicism, featured in the Catholic Gentleman

“The Catholic Church has dealt with mental illness for quite some time. Long before our modern system of mental health, the hospital at Geel, Belgium was established under the patronage of Saint Dymphna, the patron saint of those suffering from mental illness. A good seven centuries before psychiatrists opened offices, the good nuns in Geel introduced a system to take care of the mentally ill, and some of these patients even found healing through treatment and prayer.

As a convert, this information was quite helpful. While my Evangelical church denied mental illness and only told me to pray against it, I found that medieval nuns had the foresight to start treating those tortured by the mind. Our Catholic Church is still learning, and she offers many great resources.

Some of our finest saints, such as Venerable Francis Mary Paul Libermann and Bl. Teresa of Calcutta, suffered great bouts of depression. While they would be struck to the heart with grief, they still found comfort in their faith. Ven Francis Libermann once wrote,

“I never cross a bridge without the thought of throwing myself over the parapet, to put an end to these afflictions. But the sight of my Jesus sustains me and gives me patience.”

The Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote moving words about his afflictions in the “Terrible Sonnets,” and was especially heartbroken by what seemed like the silence of God in the face of his suffering. One cannot read his poetry and not be moved to compassion for him.

I bring these figures up to show that you are not abnormal; you have intercessors in heaven and on Earth who do know that the mind has many mountains and cliffs. Perhaps it is not always enough, but I know that the loneliness can be the worst part of depression. Knowing that I am indeed among friends in my suffering has been enough for me to keep going and to find hope.

MEDITATE ON CHRIST, ASK HIS SAINTS FOR HELP

I find great comfort in the Incarnation. We as Catholics believe in a God whose love for us is so powerful that he took on our lowly nature in order to redeem it. Christ didn’t become human just to teach us some new lessons; He shows us a whole new way to be human and, ultimately, how to share in His divinity.

In my darkest moments, when I truly was giving in to despair, I found that saying the Jesus Prayer and meditating on the Nativity of Our Lord was enough to let me go on another day and pursue help. In those moments, knowing that Christ was and is among us enabled me to find just enough light and comfort to believe that life was sweeter than death.

Prayer is very hard when you are depressed. I, for one, have nagging doubts when I go through my black dog days. God seems silent and I wonder where He is and what He’s doing. All the same, I do pray, and peace eventually comes. In one case, it took me two years of praying, but peace did come. Mother Teresa’s dark night of the soul lasted several years, but she endured. You can find strength in the same faith.

If you are praying and meditating and the words do not come, then sit in silence. Find an icon or an adoration chapel and utter the words, “You are God, I am not. Please help.” If nothing else, your mind will slow down and will shift its focus to God, who sustains all life and is the source of our strength.

I know this is hard, and sometimes you will want to give up. If you can do nothing else, try to take comfort in knowing that Christ didn’t die and rise again just to leave you alone. Find the saints who did suffer from grief and depression and ask them for help. They, more than any other, are eager to come to your aid.

SEEK TO TURN YOUR MIND TO THE GOOD

My MDD is a lifetime condition that is not likely to be cured except by a miracle. While there may be some forces contributing to your depression that are beyond your control, such as growing up in a troubled home or experiencing a difficult period of your life, there are other things that you can control, and it can be helpful to focus on them.

It’s perfectly normal to want to find an outlet for your depression. In my own and my family history, that has included a cocktail of food, sex and booze. I don’t need to tell you why those are bad ideas.

Instead of harmful behavior, seek to find constructive outlets for depression. I know that a walk can be helpful, and exercise has a profound effect on your mood. It not only takes your mind off of things outside of your control, but it elevates your mood and gives you something to work towards. I personally love reading and writing. Perhaps you have a passion and your depression has made you lose interest in it. But I assure you, you will find the fire of passion coming back if you work at it for even an hour. Even if you do something as simple as clean your house or, if your depression quite sever, get up and dress yourself well, it’s a small accomplishment you can take pride in.

As you probably know, your situation has the ability to give you understanding and greater empathy. Reach out to folks to talk about it, especially if they seem to be going through similar frustrations. You will relieve loneliness, a great problem of our isolated age, and also help to build a support network for you and others.

The point of all my suggestions is to not let your grief and depression rule over all your life but to find the small things you can control and do good with them. Believe me, it’s much harder than I’m making it sound, but it can be done.

To go back to prayer, I do firmly believe that offering up your sufferings for the conversion of the world and the souls in purgatory can do great things. You are turning your mind to charity, and doing so will teach your heart to love people in the midst of grief. Christ will use your prayers and tears to bring more souls to Him.

SEEK HELP, IF YOU NEED IT

While mental illness has a stigma in our society, there is no shame in seeking help. Not everyone needs medicine or therapy, but it is there for those who do. In many cases, your priest is not unfamiliar with mental illness and can be a great help. Not all priests can give you full counseling, but they can be men who you can talk to and pray with and who can offer resources for further help. Likewise, I have met many fine nuns whose wisdom has helped through many trials, and there are few weapons as powerful as a nun’s intercession.

In all things, your victory is in perseverance. As I said above, I often can’t even leave my house on particularly bad days and I have no doubt some of you are right there with me. But if we can claim small victories like seeking help and taking steps to finding comfort, then we are on the path to a greater victory.

Finally, let’s pray to the Virgin Mary, the Mother of God and the Joy of all Who Sorrow. Ask her to help you and all who are plagued by grief and depression.”

-please click on the image for greater detail

-please click on the image for greater detail

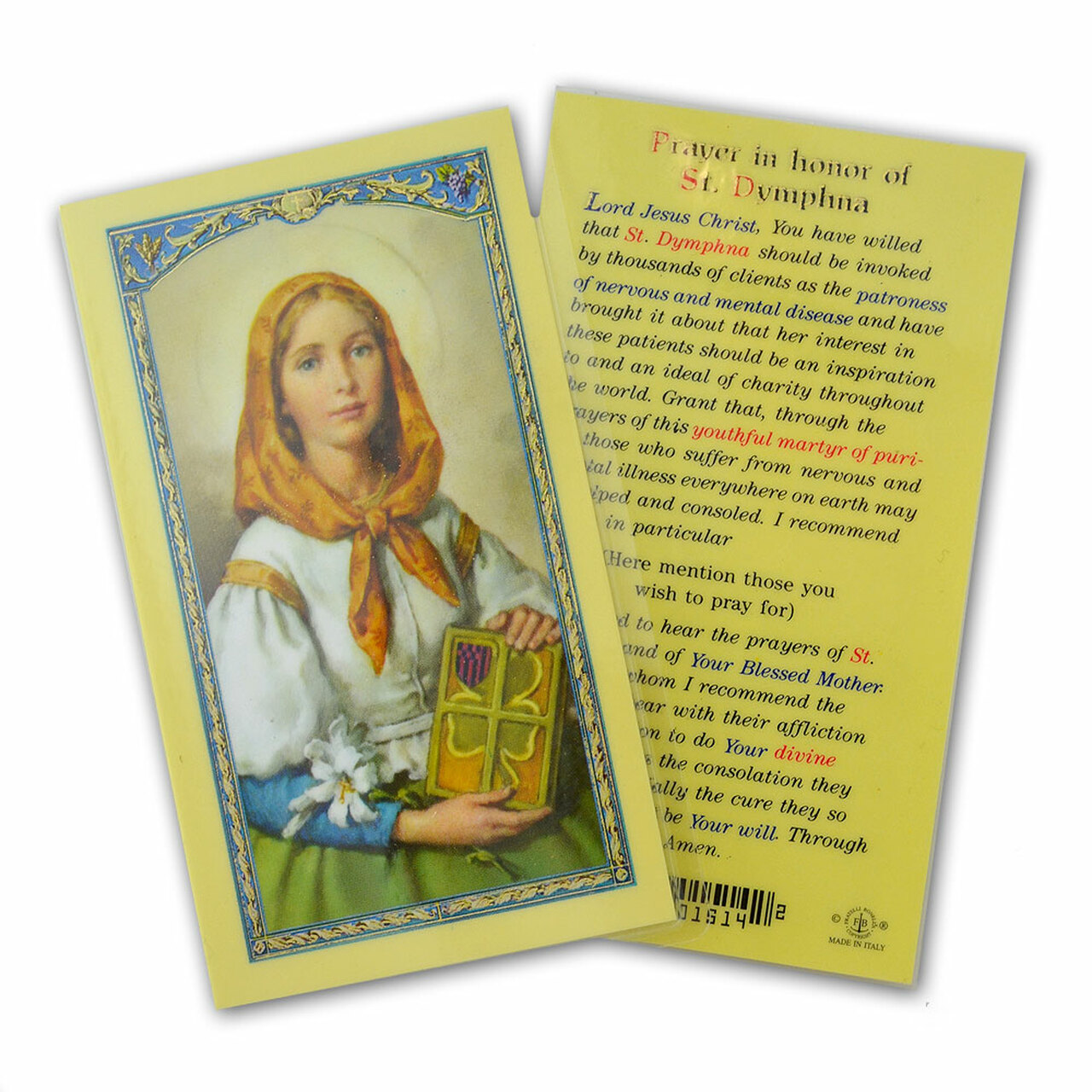

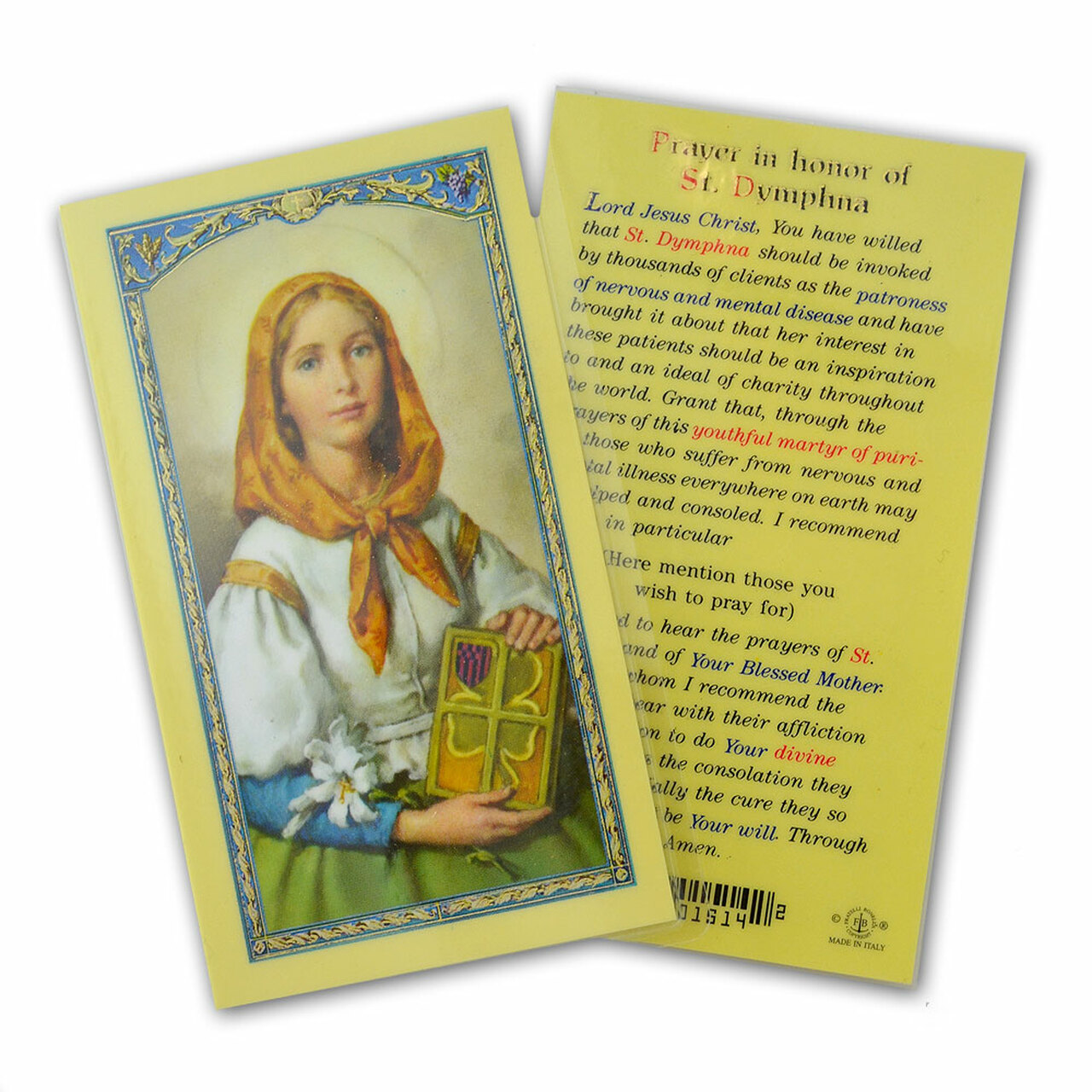

Lord Jesus Christ, Thou hast willed that St. Dymphna should be invoked by thousands of clients as the patroness of nervous and mental disease and have brought it about that her interest in these patients should be an inspiration to and an ideal of charity throughout the world. Grant that, through the prayers of this youthful martyr of purity, those who suffer from nervous and mental illness everywhere on earth may be helped and consoled. I recommend to Thee in particular (here mention those for whom you which to pray).

Be pleased to hear the prayers of St. Dymphna and of Thy Blessed Mother. Give those whom I recommend the patience to bear with their affliction and resignation to do Thy divine will. Give them the consolation they need and especially the cure they so much desire, if it be Thy will. Through Christ, Our Lord. Amen.

-“Martyrdom of St. Dymphna and St. Gerebernus”, between 1603-1651, oil on canvas, height: 176 cm (69.2 in), width: 206 cm (81.1 in), Bavarian State Painting, Schleißheim State Gallery, Attributed to Jacques de l’Ange (f 1630 – 1650), Attributed to Gerard Seghers (1591–1651), please click on the image for greater detail

Good Saint Dymphna, great wonder-worker in every affliction of mind and body, I humbly implore your powerful intercession with Jesus through Mary, the Health of the Sick, in my present need. (Mention it.) Saint Dymphna, martyr of purity, patroness of those who suffer with nervous and mental afflictions, beloved child of Jesus and Mary, pray to them for me and obtain my request.

(Pray one Our Father, one Hail Mary and one Glory Be.)

Saint Dymphna, Virgin and Martyr, pray for us.

Love & Heaven’s Joy!!!! BEAR YOUR CROSSES!!!! We must LEARN HOW TO SUFFER!!! Lk 9:23-24 It is HIS will!! And we do not need to know why, in this life! His will be done!!! PRAY!!! How else will you survive anything??

Matthew