-by Br John Mark Solitario, OP

“As Mother Teresa passed through the airport security checkpoint, she had to endure that embarrassing procedure that is part and parcel of our troubled times: “Any weapons on your person?” Unexpectedly, the childlike yet remarkably bold sari-clad woman replied in the affirmative! She did have a weapon. She then indicated the Rosary beads dangling from her hand.

This story is told as one of many insightful accounts in Marian Father Donald H. Calloway’s recently published Champions of the Rosary: The History and Heroes of a Spiritual Weapon. Many Dominicans throughout the world have endorsed this book for its historical and practical value. Fr. Bruno Cadore, successor to St. Dominic and Master of the Order of Preachers, hopes that it will help form “fervent and enthusiastic apostles of the rosary for our times.” But how?

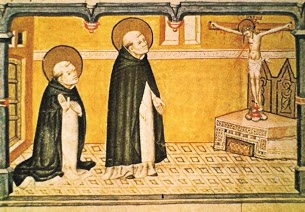

Fr. Calloway presents a careful and very readable history of the Rosary’s development and its significance in the spreading of the Gospel. He traces it back to medieval accounts of prayer beads used by monks and soldiers to recite the “Angelic Salutation” (cf. Lk 1:28) and the “Our Father.” This led to the more widespread popularity of the “Psalter of our Lady,” some 150 “Hail Mary’s” mirroring the monastic chanting of the Psalms. Then came the Dominican innovation: pre-existing prayer beads met the friar-preacher’s desire to instill the saving mysteries of Christ’s life in the hearts and imaginations of the faithful. From St. Dominic onward, the “Hail Mary” became “a weapon and a rose” to defend faith in the God who became man and to draw close to the Mother who leads us to salvation in her Son. And the prayer became immensely popular!

Champions of the Rosary traces the spiritual impact of this “Gospel of Jesus Christ on a string of beads,” worn and prayed by countless priests, brothers, nuns, sisters, and lay confraternity members over the years. Indeed, it appears that Christian civilization was advanced at several crucial junctures through the faithful praying of the Rosary. Victories that saved Christian Europe at Lepanto and Vienna, the devotional intuition of suffering indigenous peoples in America and Asia, and apparitions of the Blessed Virgin especially prevalent in recent times all testify to the power of this prayer. In addition to praising its many virtues, Fr. Calloway addresses the challenges that this very Catholic devotion has posed to various figures and times, from Martin Luther to the scientific concerns of the 20th century. Most of all, this book boldly fosters zeal by reflecting on the lives that have been transformed through praying the Rosary.

Fr. Calloway turns to a host of personal witnesses to complete his case for the authenticity and power of this devotion. Twenty-six “champions of the Rosary” (including St. Dominic, Bl. Bartolo Longo, and St. Teresa of Calcutta) have remarkable stories about the Rosary and its role in advancing the Gospel and crushing temptations to doubt and despair. He devotes special attention to examining Rosary artwork in order to show the prevalence and beauty of this devotion. Finally, a section with Scripture-based meditations, explanations of relevant indulgences, and information on joining associations devoted to the Rosary gives us what we need to take up this much-used tool of Christian holiness.

It has been said that the Rosary is refreshment for spiritual giants and food for beginners in faith. As much as we desire peace in this tumultuous world and want harmony in our own lives, we might be anxious to find anything that can lead us toward that for which we thirst. Fr. Calloway’s book joins Mother Teresa in suggesting a “weapon” more powerful and penetrating than any blade or pistol: “Peace will come into the world through Mary. But first in our hearts. Pray the Rosary with faith.””

Love,

Matthew