-Hell Receiving Fallen Angels, Dante’s Paradise Lost illustration, by Gustave Dore (1832-1883)

-by Edward Freser is writer and philosopher living in Los Angeles. He teaches philosophy at Pasadena City College. His primary academic research interests are in the philosophy of mind, moral and political philosophy, and philosophy of religion.

“How is it that anyone ever goes to hell? How could a loving and merciful God send anyone there? How could any sin be grave enough to merit eternal damnation? How could it be that not merely a handful of people, but a great many people, end up in hell, as most Christian theologians have held historically?

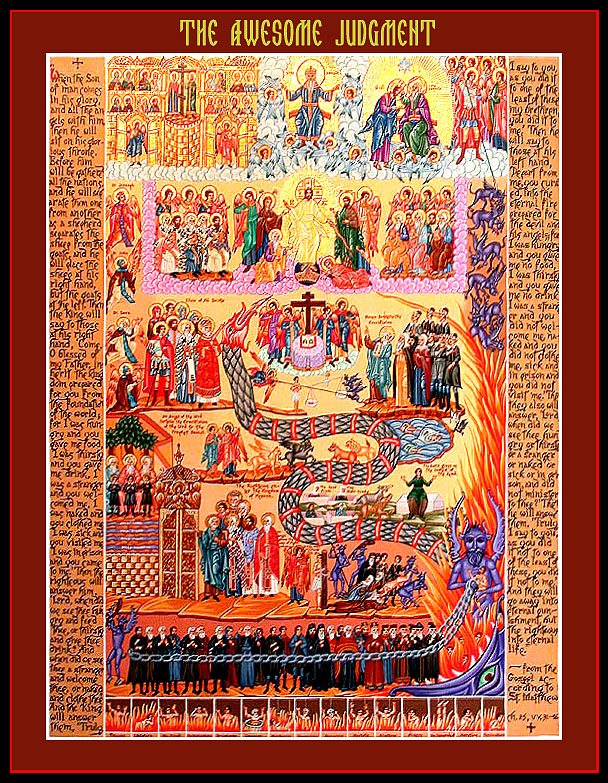

A complete treatment of the subject would be complex, because there are a number of relevant subsidiary issues, some of them complex in themselves. These issues include: the difference between the supernatural end of the beatific vision and our merely natural end, and hell as the loss of the former; the difference between the sufferings of hell and the state of a soul either in limbo or in purgatory; the precise nature of the sufferings of hell, and the different kinds and degrees of suffering corresponding to different vices; what it is that makes a particular action – including actions modern people tend to regard as merely minor sins or not sins at all – mortally sinful or apt to result in damnation; what can be known by way of purely philosophical analysis and what is known only via special divine revelation; the proper interpretation of various scriptural passages and the authority of the statements of various councils, popes, and saints; what is wrong with various popular misconceptions which cloud the issues (crude images of devils with pitchforks and the like); and so forth.

I’m not going to address all of that here. What I will address is what I take to be the core issue, in light of which the others must be understood, which is the manner in which hell is something chosen by the one who is damned, where this choice is in the nature of the case irreversible. In particular, I will approach this issue the way it is approached by Aquinas and other Thomists.

Many misunderstandings arise because people often begin their reflections on this topic at the wrong point. For example, they begin with the idea that the damned end up in hell because of something God does, or with the idea that there is something in some particular sin (a particular act of theft or of adultery, say) that sends them there. Now, I would by no means deny that the damned are damned in part because of something God does, and that particular sins can send one to hell. The point, again, is just that there is something more fundamental going on in light of which these factors have to be understood.

Obstinate angelic wills

It is useful to begin with the way in which, on Aquinas’s analysis, an angel is damned. (See especially Summa Theologiae I.64.2; De Veritate, Question 24, Article 10; and On Evil, Question XVI, Article 5.) Here, as with the images of devils with pitchforks, the unsympathetic reader is asked to put out of his mind common crude images, e.g. of creatures with white robes, long golden hair, and harps. That is not what an angel is. An angel is instead an incorporeal mind, a creature of pure intellect and will. It is also worth emphasizing for the skeptical reader that whether or not one believes in angels is not really essential to the subject addressed in this post. Think, if you must, of what is said in this section as a useful thought experiment.

On Aquinas’s analysis, angels, like us, necessarily choose what they choose under the guise of the good, i.e. because they take it to be good in some way. (See my article “Being, the Good, and the Guise of the Good,” reprinted in Neo-Scholastic Essays, for exposition and defense of the Thomistic account of the nature of human action.) And as with us, an angel’s ultimate good is in fact God. But, again like us, they can come to be mistaken about what that ultimate good is. That is to say, like us, an angel can erroneously take something other than God to be its ultimate good.

However, the nature of this error in the case of an angel is somewhat different from the nature of the error we might commit. In us, a sudden and fleeting passion might distract us from what is truly good for us and lead us to pursue something else instead. But passions are essentially corporeal, i.e. they exist only in creatures which, like us, have bodies. Angels do not have bodies, so passions play no role in leading them into error.

A second way we can be led into error is through the influence of a bad habit, which pulls us away from what is truly good for us in a more serious way than a fleeting passion might. For Aquinas, there is indeed habituation in angels, as there is in us. However, there is a difference. In our case, we have several appetites pulling us in different directions because of our corporeal nature. Because we are rational animals, our will is directed at what the intellect conceives as the good, but because we are rational animals, we also have appetites which move us toward the pursuit of other, sub-intellectual things, such as food, sexual intercourse, and so forth. These appetites compete for dominance, as it were, which is why in a human being, even a deeply ingrained habit can be overcome if a competing appetite is strong enough to counter it.

Angels are not like this, because they are incorporeal. They have only a single appetite – the will as directed toward what the intellect takes to be good. There is no competing appetite that can pull the angel away from this end once the will is directed toward it. Once the will is so directed, habituation follows immediately and unchangeably, because of the lack of any other appetite that might pull an angel is some different direction.

A third way we can be led into error is intellectually, by virtue of simply being factually mistaken about what is in fact good for us. Here too, angels can make the same sort of error. But here too, the nature of the error is different in the case of an angel. The way we come to know things is discursively. We gather evidence, weigh it, reason from premises to conclusion, and so on. All of this follows upon our corporeality – in particular, the way we rely upon sensory experience of particular things in order to begin the process of working up to general conclusions, the way we make use of mental imagery as an aid to thought, and so forth. Error creeps in because passion or habituation interferes with the proper functioning of these cognitive processes, or because we get the facts wrong somewhere in the premises we reason from, or the like. Further inquiry can correct the error.

There is nothing like this in angels. For Aquinas, an angel knows what it knows, not discursively, but immediately. It doesn’t reason from first principles to conclusions, for example, but knows the first principles and what follows from them all at once, in a single act. Now, because there is no cognitive process by which an angel knows (as there is in us), there is no correction of a cognitive process that has gone wrong, either by gathering new information, resisting passions, or overcoming bad habits. If an angel goes wrong at all, it is not (as we are) merely moving in an erroneous direction but where this trajectory might be reversed. It simply is wrong and stays wrong.

For Aquinas, then, an angel’s basic orientation is set immediately after its creation. It either rightly takes God for its ultimate end, or wrongly takes something less than God for its ultimate end. If the former, then it is forever “locked on” to beatitude, and if the latter, it is forever “locked on” to unhappiness. There is no contrary appetite that can move it away from what it is habituated to, and no cognitive process that can be redirected. The angel that chooses wrongly is thus fallen or damned, and not even God can change that any more than he can make a round square, for such change is simply metaphysically impossible insofar as it is contrary to the very nature of an angelic intellect.

Obstinate human wills

Again, human beings are different, because they are corporeal. Or, to be more precise, they are different while they are corporeal. For a human being has both corporeal and incorporeal faculties. When the body goes, the corporeal faculties go. But the incorporeal faculties – intellect and will, the same faculties that an angel has – carry on, and the human being persists as an incomplete substance. (See my article “Kripke, Ross, and the Immaterial Aspects of Thought,” also reprinted in Neo-Scholastic Essays, for defense of the incorporeality of the intellect. See chapter 4 of Aquinas for exposition and defense of the Thomistic argument for the immortality of the soul.)

This brings us to Aquinas’s treatment of the changeability or lack thereof of the human will. (See especially Summa Contra Gentiles Book 4, Chapter 95.) Prior to death, it is always possible for the human will to correct course, for the reasons described above. A passion inclining one to evil can be overcome; a bad habit can be counteracted by a contrary appetite; new knowledge might be acquired by which an erroneous judgment can be revised. Hence, at any time before death, there is at least some hope that damnation can be avoided.

But after death, Aquinas argues, things are different. At death the soul is separated from the body, a separation which involves the intellect and will – which were never corporeal faculties in the first place – carrying on without the corporeal faculties that influenced their operation during life. In effect, the soul now operates, in all relevant respects, the way an angelic intellect does. Just as an angel, immediately after its creation, either takes God as its ultimate end or something less than God as its ultimate end, so too does the disembodied human soul make the same choice immediately upon death. And just as the angel’s choice is irreversible given that the corporeal preconditions of a change are absent, so too is the newly disembodied soul’s choice irreversible, and for the same reason. The corporeal preconditions of a change of orientation toward an ultimate good, which were present in life, are now gone. Hence the soul which opts for God as its ultimate end is “locked on” to that end forever, and the soul which opts instead for something less than God is “locked on” to that forever. The former soul therefore enjoys eternal beatitude, the latter eternal separation from God or damnation.

The only way a change could be made is if the soul could come to judge something else instead as a higher end or good than what it has opted for. But it cannot do so. Being disembodied, it lacks any passions that could sway it away from this choice. It also, like an angel, now lacks any competing appetite which might pull its will away from the end it has chosen. Thus it is immediately habituated to aiming toward whatever, following death, it opted for as its highest end or good – whether God or something less than God. Nor is there any new knowledge which might change its course, since, now lacking sensation and imagination and everything that goes with them, it does not know discursively but rather in an all-at-once way, as an angel does. There is no longer any cognitive process whose direction might be corrected.

But might not the resurrection of the body restore the possibility of a course correction? Aquinas answers in the negative. The nature of the resurrection body is necessarily tailored to the nature of the soul to which it is conjoined, and that soul is now locked on to whatever end it opted for upon death. The soul prior to death was capable of change in its basic orientation only because it came into existence with its body and thus never had a chance to “set,” as it were. One it does “set,” nothing can alter its orientation again.

An analogy might help. Consider wet clay which is being molded into a pot. As long as it remains wet, it can alter its basic shape. Once it is dried in the furnace, though, it is locked into the shape it had while in the furnace. Putting it in water once again wouldn’t somehow make it malleable again. Indeed, the water would be forced to conform itself to the shape of the pot rather than vice versa.

The soul is like that. While together with the body during life, it is like the wet clay. Death locks it into one basic orientation or another, just as the furnace locks the clay into a certain definite shape. The restoration of the body cannot change its basic orientation again any more than wetting down a pot or filling it with water can make it malleable again.

The influence of the passions and appetites

Now, what choice is a soul likely to make immediately upon death? Obviously, the passions and appetites that dominated it in life are bound to push it very strongly in one direction or another. For example, a person who at the end of his life is strongly habituated to loving God above all things is very unlikely, in his first choice upon death, to regard something other than God as his ultimate end or good. A person who at the end of his life is strongly habituated to hating God is very unlikely, in his first choice upon death, to regard God as his ultimate end or good. A person who, at the end of his life, is strongly habituated to regarding some specific thing other than God as his ultimate good – money, sex, political power, etc. — is very likely, in his first choice upon death, to regard precisely that thing as his ultimate good or end. It is very likely, then, that these various souls will be “locked on” forever to whatever it was they were habituated to valuing above all things during life on earth.

Of course, what counts as regarding God as one’s ultimate end requires careful analysis. Someone might have a deficient conception of God and yet still essentially regard God as his ultimate good or end. One way to understand how this might go is, in my view, to think of the situation in terms of the doctrine of the transcendentals. God is Being Itself. But according to the doctrine of the transcendentals, being – which is one of the transcendentals – is convertible with all the others, such as goodness and truth. They are really all the same thing looked at from different points of view. Being Itself is thus Goodness Itself and Truth Itself. It seems conceivable, then, that someone might take goodness or truth (say) as his ultimate end, and thereby – depending, naturally, on exactly how he conceives of goodness and truth – be taking God as his ultimate end or good, even if he has some erroneous ideas about God and does not realize that what he is devoted to is essentially what classical theists like Aquinas call “God.” And of course, an uneducated person might wrongly think of God as an old man with a white beard, etc. but still know that God is cause of all things, that he is all good, that he offers salvation to those who sincerely repent, etc. By contrast, it seems quite ridiculous to suppose that someone obsessed with money or sex or political power (for example) is really somehow taking God as his ultimate end without realizing it.

In any event, the strength of the passions and appetites is one reason why the sins attached to them are so dangerous, even when they are not as such the worst of sins. To become deeply habituated to a certain sin associated with a particular appetite or passion is to run grave risk of making of that sin one’s ultimate end, and thus damning oneself. This is why the seven deadly sins are deadly. For example, if one is at the time of one’s death deeply habituated to envy or to sins of the flesh, it is naturally going to be difficult for one’s first choice upon death not to be influenced by such habits.

There is this “upside” to a sin like envy, though – it offers the sinner no pleasure but only misery. That can be a prod, during life, to overcoming it. Sins of the flesh, however, typically involve very intense pleasure, and for that reason it can be extremely difficult to overcome them, or even to want to overcome them. In addition, they have as their “daughters” such effects as the darkening of the intellect, self-centeredness, hostility toward spiritual things, and the like. (I discussed Aquinas’s account of the “daughters of lust” in an earlier post.)

It is said that at Fatima the Blessed Virgin declared that more souls go to hell for sins of the flesh than for any other reason. Whatever a skeptic might think of Fatima, this basic thesis is, if one accepts the general natural law account of sexual morality together with Aquinas’s account of the obstinacy of the soul after death, quite plausible. That is not because sins of the flesh are the worst sins. They are not the worst sins. It is rather because they are very common sins, easy to fall into and often difficult to get out of. Nor does it help that in recent decades they are, more than any other sins, those that a vast number of people absolutely refuse even to recognize as sins.

A world awash in sexual vice of all kinds and “in denial” about it is a world in which a large number of people are going to be habituated to seeking sexual pleasure above all things, and to become forever “locked on” to this end as their perceived ultimate good. (It is very foolish, then, for churchmen and other Christians to think it kind or merciful not to talk much about such sins. That is like refusing to warn joggers of the quicksand they are about to fall into. And positively downplaying the significance of such sins and even emphasizing instead the positive aspects of relationships (e.g. adulterous relationships) in which the sins are habitually committed is like encouraging the joggers to speed up. One thinks of Ezekiel 33:8.)

Whatever might be said about sins of the flesh per se, however (and I have said a lot about that subject in other places) the main point is to emphasize how deeply the passions and appetites “prepare” a soul for the decisive choice it is going to make, especially when there is pleasure attached to the indulgence of the passions or appetites. What is true of illicit sexual indulgence is true also, if often in a less intense way, of the indulgence of other passions and appetites. There is, for example, the pleasurable frisson of self-righteousness that can accompany the judgment of others or the indulgence of excessive or misdirected anger. There is the pleasure a sadist might get from dominating or humiliating others. And so forth.

There can also be a deficiency in the passions and appetites. For example, one can show insufficient anger at injustice and evil and thus lack any resolve to do something about it. Or one might be deficient in the amount of sexual desire one has for one’s spouse or in the amount of affection one is inclined to show one’s children. Deficiencies in passions and appetites can thus keep us from pursuing what is good, just as excesses in passions and appetites can lead us to pursue what is not good.

The passions and appetites are like heat applied to wet clay. The longer the soul is pushed (or not pushed) by a passion or appetite in a certain direction, the more difficult it is to reorient the soul, just as it is more difficult to alter the shape of wet clay the longer heat is applied and the drier the clay gets.

Those interested in further reading on this subject are advised to read, in addition to the texts from Aquinas cited above, Abbot Vonier’s The Human Soul, especially chapters 29-33; Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange’s Life Everlasting and the Immensity of the Soul, especially chapters VII-IX; and Cardinal Avery Dulles’s First Things article “The Population of Hell.” (Most readers will be familiar with Garrigou-Lagrange and Dulles. If you are not familiar with Vonier, I highly recommend tracking down everything written by him that you can get your hands on.)”

Lord, have mercy on us. Christ have mercy on us.

Lord, have mercy on us. Christ, hear us, Christ, graciously hear us.

God, the Father of heaven, Have mercy on us.

God the Son, Redeemer of the world, Have mercy on us.

God, the Holy Spirit, Have mercy on us. Holy Trinity, One God, Have mercy on us.

-Litany of the saints

Matthew