-Dorset Martyrs Memorial, Gallows Hill, Dorchester, England

There is a very special communion between the laity and the ordained. Not merely too many calories delivered to rectories at holidays, or generous gifts for Father from time to time; one priest who received a new car famously quipped, “All THIS!!!! AND eternal life, too!!!”

It is recorded, often, in history, when oppressed, persecutors believed by destroying the priesthood, they would succeed in in destroying the faith. Untrue, time and time, again. When Asian missionaries returned, it is recorded, to Far Eastern missions where once they evangelized after several hundred years of absence, the clandestine faith still survived, albeit adapted to life without clergy, but it persisted. It is stronger than that. It always has been. So, “though the mountains fall into the sea”, yet shall we trust in His promises. The gates of Hell shall not prevail against us.

Persecution in England in the late 17th century was part of a crackdown by the Elizabethan government after the Decree of 1585, which made it an offense punishable by death to seek ordination to the priesthood oversees and return to England. This story, like others just like it, is of Catholic laity and that special communion with the ordained.

John, Thomas, John and Patrick were executed together at Dorchester on July 4, 1594: John Cornelius, who trained for the priesthood at Douai and Rome, was arrested in April; his companions were arrested for assisting him. John became a Jesuit while imprisoned in London. All of them were from Ireland:

Father John Cornelius, their leader, was born in 1557 to Irish parents who had moved to Great Britain. A Dorsetshire Catholic knight, Sir John Arundel, sent him to Oxford University to study. But John was too Catholic in his convictions to be pleased with the “new religion” that dominated the University. Feeling called rather to the Catholic priesthood, he crossed the Channel and enrolled at the English college in Rheims for holy orders. From Rheims he went on to the English College in Rome to complete his theology, and it was at Rome that he was ordained a priest.

Return to England as a Catholic priest was at that time forbidden under pain of death. But Father John, a man of prayer and zeal, saw in that law a challenge rather than a deterrent, as did the rest of the contemporary English priests who set service to persecuted Catholics as their top priority. His assignment was to the Catholics of Dorset. These priests’ ministry was a “cloak-and-dagger” operation, since they were always in danger of discovery and arrest. Their capture could mean also the arrest and punishment of anybody who assisted them.

Naturally, the missionaries’ terms of service were usually short, for the police were alert and aggressive. Cornelius (he also went by the alias of Mohun, although his real surname seems to have been O’Mahony) was finally seized by the sheriff of Dorset on April 24, 1594, at the Chideock Castle of Lady Arundel.

Having seized the priest by surprise, the Sheriff was about to hurry him off hatless. Now, in that hat-conscious age, to be hatless was to appear uncivilized. Thomas Bosgrave, a gallant young Cornish nephew of Sir John Arundel and a witness to the arrest, stepped forward and offered Father John his own hat. “The honor I owe to your function,” he declared, “may not suffer me to see you go bareheaded!” It was a simple gesture of charity to a priest, but he was to pay for his piety. The Sheriff promptly arrested Bosgrave, too, for “aiding” a Catholic clergyman. He likewise arrested two serving-men of this Catholic household, Dubliners John Carey and Patrick Salmon. Content, no doubt, with the day’s work, the county official then led his catch off to jail.

Cornelius, the most important of them, was taken to London to be examined by Queen Elizabeth’s Privy Council. The Council had him stretched on the rack to force him to name all those who had given him shelter or assistance. Torture would not open his lips, however, so he was sent back to Dorchester for trial, along with the three lay captives. On July 2, the court declared the priest guilty of high treason under the law that forbade Catholic priests to enter England and remain there. Bosgrave, Carey and Salmon were pronounced guilty of felony for aiding and abetting Father John. The sentence was the same for all: hanging, drawing, and quartering.

After the court had published its judgment, it offered all four men a reprieve if they would give up their Catholic faith. All four refused.

The execution took place at Dorchester two days later. The three laymen were hanged first. John Carey is reported to have said as the noose hung before his face, kissing the rope, “Oh! Precious collar!” Each made a Catholic profession of faith before the trap was sprung. Father John then kissed the feet of his hanging companions. He then kissed the gallows with the words of Saint Andrew, “O Cross, long desired.” He was not allowed to make any formal statement; but he did manage to state that he had been lately admitted into the Jesuits, and would have been en route to the Jesuit novitiate in Flanders had he not been arrested.

Dorset Martyrs Memorial, Gallows Hill, Dorchester

The Dorset Martyrs Memorial at Gallows Hill on South Walks, Dorchester was created by Dame Elisabeth Frink and was erected in 1986. It was funded by institutions and individuals of all denominations and the Arts Council of Great Britain through South West Arts.

The memorial represents two martyrs facing Death and commemorates all Dorset men and women who suffered for their faith and, in particular, seven known Catholics who were executed where the Memorial now stands, including —

John Cornelius SJ, Priest, executed 4 July 1594

John Cornelius was born in Bodmin of Irish descent and was sent to Exeter College, Oxford by Sir John Arundell. He was ordained in 1584 at the English College in Rome.

John Cornelius was a Chaplain to the Arundell family at Chideock Castle where he was arrested after a search of the castle and sent to Dorchester to be tried for high treason along with

Thomas Bosgrave, John Carey and Patrick Salmon. Executed on 4 July 1594, along with Fr Cornelius, SJ.

Thomas Bosgrave was the son of Leonard Bosgrave and the grandson of Sir John Arundell, making him the great-great-grandson of Thomas Gray, 1st Marquis of Dorset and half-brother to Elizabeth of York, Queen Consort of King Henry VII.

Thomas Bosgrave, together with John Carey and Patrick Salmon, servants at Chideock Castle, was arrested and taken with John Cornelius to Dorchester where they were charged with harbouring a priest contrary to the statute of 1585.

Gallows Hill

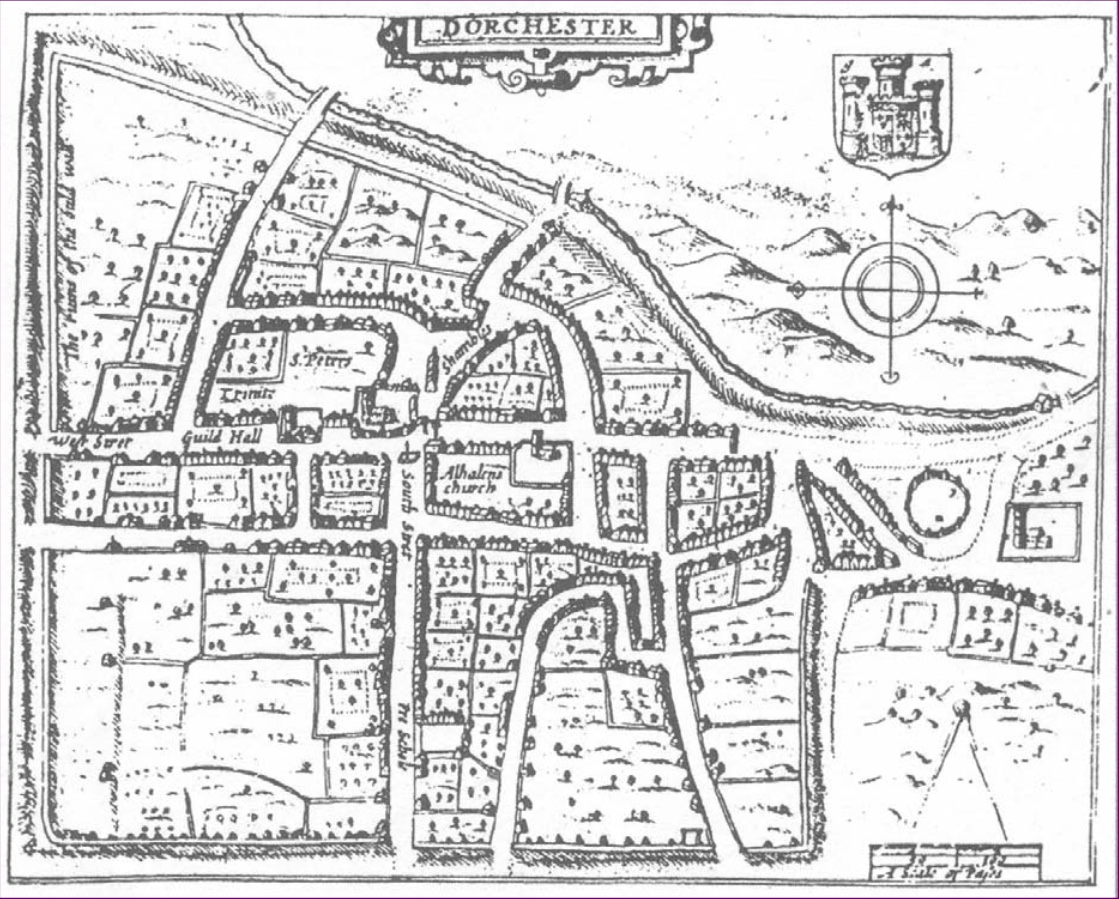

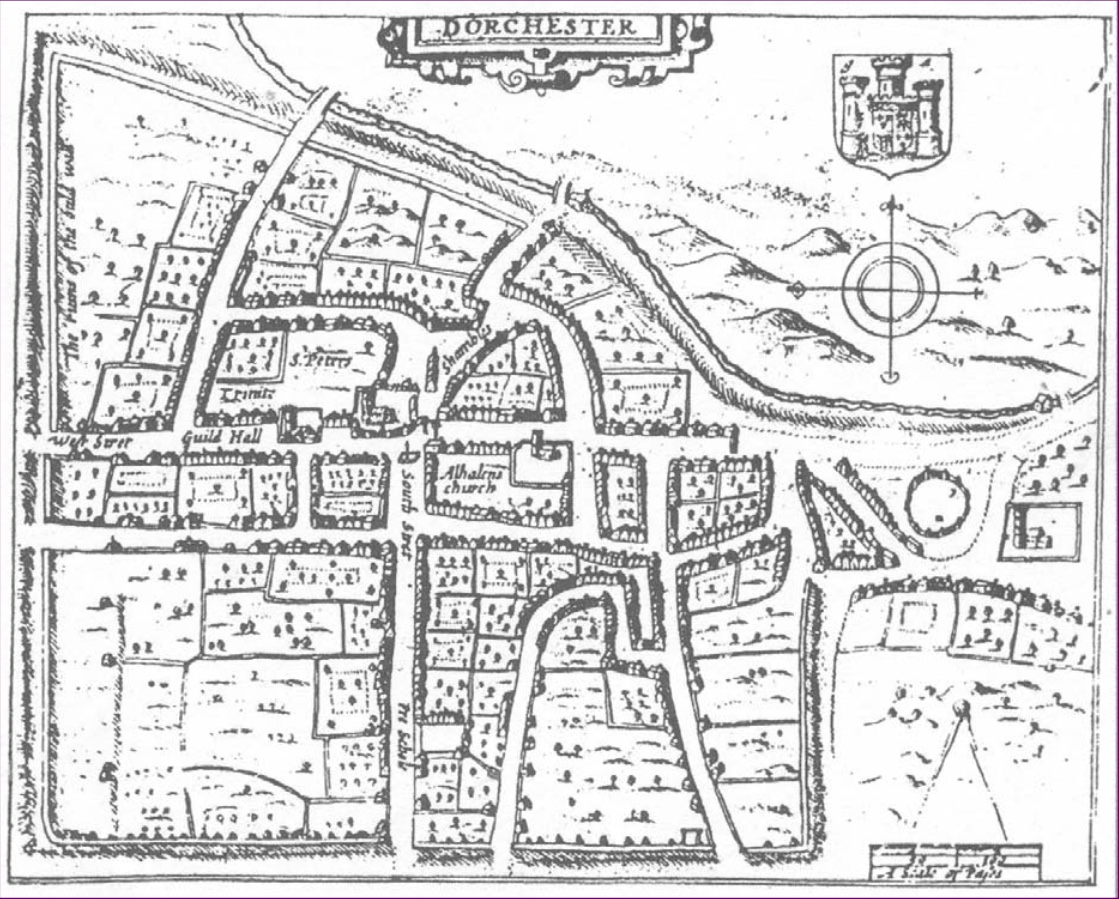

-please click on the image for a more detailed view

John Speed’s map of Dorchester was published in 1610. It shows the position of the gallows on Gallows Hill on the bottom of the map towards the right,close to the modern junction of Icen Way and South Walks. The gallows was made of two uprights and a crossbeam connecting them with enough space for a two-wheeled cart to pass through and enough space for multiple hangings. At that time the County Gaol wa son High East Street near Icen Way, which used to be called Gaol Lane.

In the 16th and 17th centuries the penalty for high treason was to be hung, drawn and quartered. The victim was tortured, imprisoned, then taken to the gallows. He or she would be cut down after a short hanging, sometimes still alive, and cruelly butchered, with the limbs being torn from the body. The dismembered corpse was often placed on gateways. This is how John Cornelius, SJ and many more died.

The gallows was removed to Maumbury Rings around 1703, which means that many of the 74 prisoners condemned to death during the ‘Bloody Assize’ following the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685 will also have been executed there.

Love,

Matthew