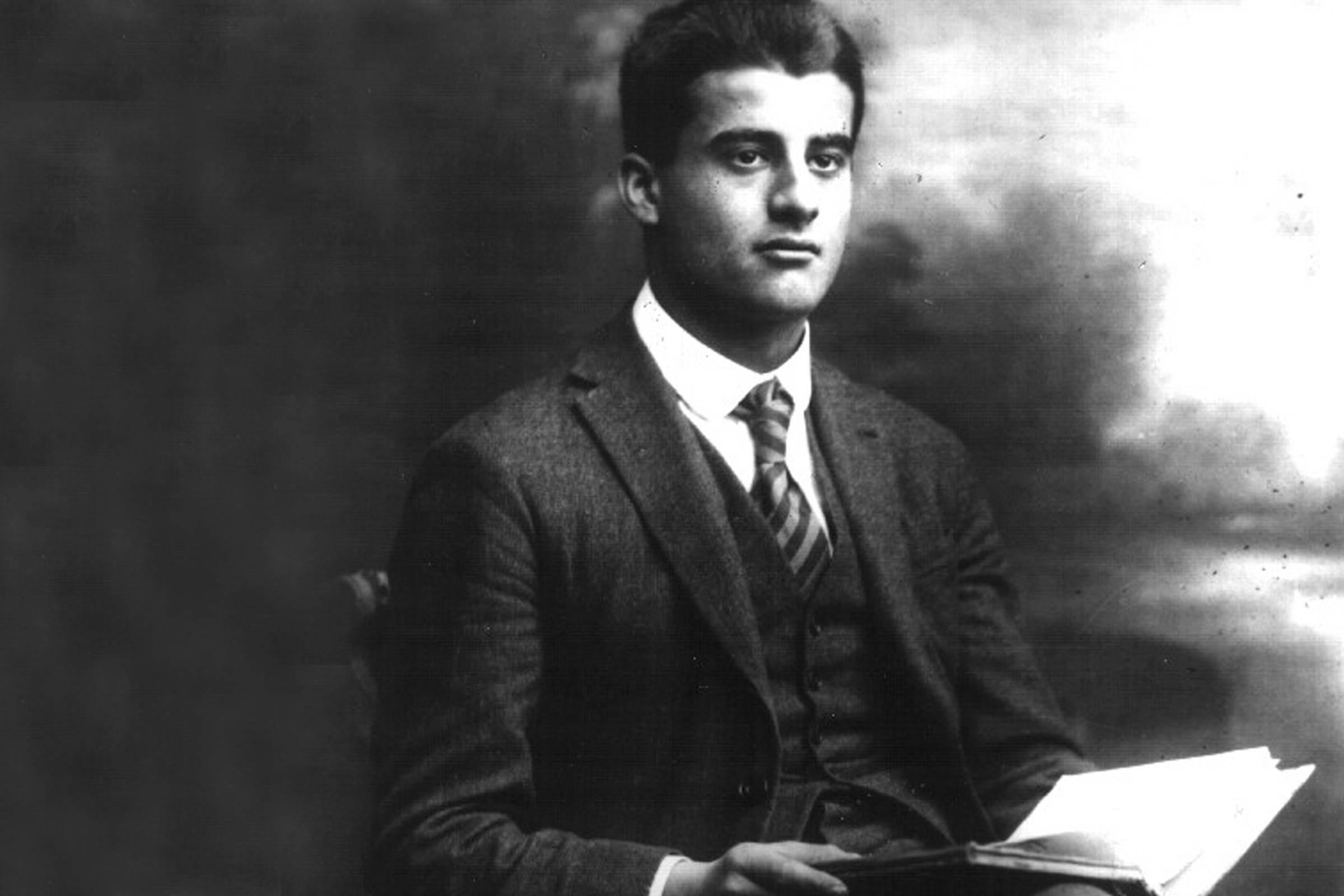

-please note the collar brooch Bl Adrian wears in this image. It’s design is of the Dominican shield, in black & white. It is a classic design, widely recognized by those familiar. I have similar lapel pins, worn on appropriate occasions!! Can I hope, too, for the blessing of martyrdom? Bl Adrian pray to our Father it may be so!!! Ultimately, His will be done!!! Viva Cristo Rey!!!!!

-by Br Samuel Clarke, OP, English Province

“After a remarkable life, Bl. Adrian Fortescue died a martyr at the strike of an executioner’s blade at Tower Hill in 1539. A husband and father, a Justice of the Peace, a Knight of the Realm, a Knight of Malta, and a Dominican Tertiary (Lay Dominican); he was at once a loyal servant of the Crown so far as he could be, but still more, he was a man of unshakeable faith.

The House of Fortescue into which Adrian was born is said to date from the Battle of Hastings where Richard le Fort saved William the Conqueror’s Life by the shelter of his “strong shield”, and thereafter was called “Fort – Escu”. His family had a history of service to the Crown although this was later complicated by the dynastic battles of The Wars of the Roses. Vicissitudes notwithstanding, his great uncle, Sir John Fortescue (d.1479) became Chief Justice of the King’s Bench (1442-61). Sir John’s writings on the law and politics of England were arguably the most significant contribution of the fifteenth century, and are still studied by lawyers and political theorists today. Adrian’s father, also named Sir John, fought for the victorious Lancastrians at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 when Adrian was but a young boy. And later in his life, Adrian’s first cousin, Anne Boleyn, became King Henry VIII’s second wife (before her eventual beheading in 1536). We can say with some justification then that the Fortescues occupied a privileged position at the Rroyal court.

The first mention of Adrian Fortescue is in 1499, by which time, aged about 23, he was already married to Anne Stonor. He lived at his wife’s family seat at Stonor Park in Oxfordshire. This estate would later become the subject of an acrimonious legal dispute between him and his relative. In 1503, on Prince Henry becoming Prince of Wales (after Prince Arthur’s death) Adrian was made a Knight of the Order of Bath. Sir Adrian took the motto Loyalle Pensée; his loyalty was indeed to be tested. By his first wife, Fortescue had two daughters: Margaret and Frances. By his second wife, Anne Rede, he had three sons and two daughters: John, Thomas, Anthony, Elizabeth, and Mary.

Like his forebears, Adrian served King Henry VIII in his ambitious military campaigns. He helped to rout the French the Battle of Spurs in 1513, and fought again in 1523. King Henry rewarded his support and in 1520 invited him to the splendorous Field of the Cloth of Gold where Henry famously wrestled with the King of France. Closer to home, Sir Adrian was made a Justice of the Peace of the county of Oxfordshire. In this period of history, royal favour could also take more peculiar forms. Sir Adrian had the dubious honour of being made a Gentleman of the King’s Privy Chamber, forerunner to the august body now known as the Privy Council.

In addition to being an assiduous servant of the Crown, Sir Adrian was evidently also a man of strong religious conviction and charity. His accounts reveal a number of benefactions to clergy and religious foundations. In 1532, he became a Knight of Devotion in the Order of Malta. The following year in July of 1533, he was admitted as a Dominican Tertiary at Blackfriars, Oxford, which he would visit from Stonor. But he also had a strong association with the Dominican Priory in London. His lodgings in the capital were in the precincts of the Blackfriars, close to the present eponymous tube station.

-Collegio di San Paolo in Rabato in Malta

Not long after becoming a Lay Dominican began what Adrian called his “trobilles”. At the start of Summer 1533, he assisted in the Coronation of his cousin, Anne Boleyn – then six months pregnant – as Queen of England. He must have realised that the marriage was not valid but perhaps thought, at that stage at least, that in the words of Sir Thomas More, it was not his business “to murmur at it or dispute upon it”. This narrow compromise was to prove short-lived.

The King’s infidelity and presumption were rebuked when the Pope refused to grant an annulment declaring Henry’s marriage to Catherine as valid on 23rd March 1534. The following month on 13th April, Bishop Fisher and Sir Thomas More refused to take the Oath of Succession. Sir Adrian was similarly arrested that same year but he was released without explanation, probably in the Spring of 1535. Fisher and More were afforded no such clemency, and the two Saints were executed in Summer 1535.

The Act of Supremacy was also passed in 1535, making Henry supreme Head of the Church “immediately under God”. As a matter of law, Henry expressly denied the Pope’s authority. A writ affirming this and dated the following year can be found in Sir Adrian’s extant Missal. Tellingly, perhaps, it has with a line struck through it: apparent evidence of his disapproval. The die, it seems, was cast.

In February 1539, Sir Adrian was again arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London. In the sitting of Parliament that Spring, a number of laws were passed in what has been described as the most servile Parliamentary session in history. Among the draconian laws enacted was a novel provision whereby a sentence of death might be passed without any trial of the accused. Under this procedure, no evidence was needed, neither could a defence be heard. Ironically, the architect of the law, Thomas Cromwell (then Lord Chancellor) was himself condemned by the same measure a year later leading to his own execution. This device was put to use on 11th May 1535 when a Bill of Attainder was passed condemning fifty people of High Treason who opposed Henry’s ecclesiastical policies. The names included Sir Adrian, Reginald Cardinal Pole, and the Countess of Salisbury.

Sir Adrian’s Book of Hours contains a Rule of Life written in his own hand, and giving an insight into the interior life of a man who exemplified holiness and virtue in his conduct. He led a life of asceticism and honour, trying to follow God’s will in all things and daily seeking the guidance of the Holy Spirit. His pursuit of God’s truth brought him to a martyr’s death on 8th July 1539 (but possibly 9th or 10th) when he was beheaded at Tower Hill. His servants were also killed for treason on the same day but were hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn. As one later account neatly puts it, “Sir Adrian Fortescue died for his faith in Him whose acts Parliament was not competent to repeal”.

Pope Leo XII declared Adrian Fortescue blessed on 13th May 1895 and as a layman, he ranks among the great Dominicans as an outstanding example to all Christians.”

Prayer:

O God, since all things are within your power, grant through the prayers of blessed Adrian, your martyr, that we who keep his feast today may become stronger in the love of your name and hold to your holy Church even at the cost of our lives. We ask this through our Lord Jesus Christ your Son, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.(-from: The Missal with readings of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes, & of Malta, London 1997) The Order of St. John of Jerusalem, aka Knights Hospitaller, has advocated devotion to Blessed Adrian as a martyr since the 17th century.

-Breast star of Knight of Grace of the Order of St John

Love,

Matthew, OP