-Carl Sundell is Professor Emeritus of English and Humanities at Quinsigamond Community College in Worcester, Massachusetts. He currently resides in Lubbock, Texas. He has authored several books and has contributed to New Oxford Review and Catholic Insight. He is currently developing a book for students of Catholic apologetics.

“I have not always been a Catholic. At the age of ten I was baptized at St. Elizabeth’s Church in Lubbock, Texas. My mother and stepfather were not churchgoers, but must have thought I was misbehaving sufficiently to require more moral guidance than they were equipped to provide. For several Sundays they took me on a tour of churches throughout the city, then asked me which one I liked. I told them I wanted to go back to the one with the bells and candles and statues and the great music and the man up front in the neat costume. “Well Carl,” my mother said, “it looks like you’re going to be a Catholic.”

On top of that, I became an altar server. That was in Carlsbad, New Mexico. During my junior year at the high school there, I had an excellent English teacher, John Hadsell. He was not a Catholic, but he introduced me to a book of Father Brown detective stories by G.K. Chesterton. One day, Mr. Hadsell radically changed my life by reading to the class St. Anselm’s ontological proof for the existence of God. Can you imagine an English teacher getting away with that today in a public high school? I was so impressed (but also confused) by Anselm’s logic that I asked him to read the proof again. He patiently did, and from that moment on began my serious search for (and later flight from) Anselm’s “Being of whom no greater being can be conceived.”

At Carlsbad I encountered another formidable influence. In the school library I came across a book of essays by Jacques Maritain, the premier Catholic philosopher of the twentieth century. I learned that he was living at Princeton University and wrote him a letter congratulating him on his book. Several weeks later I was in glorious shock after receiving a kindly reply and words of encouragement.

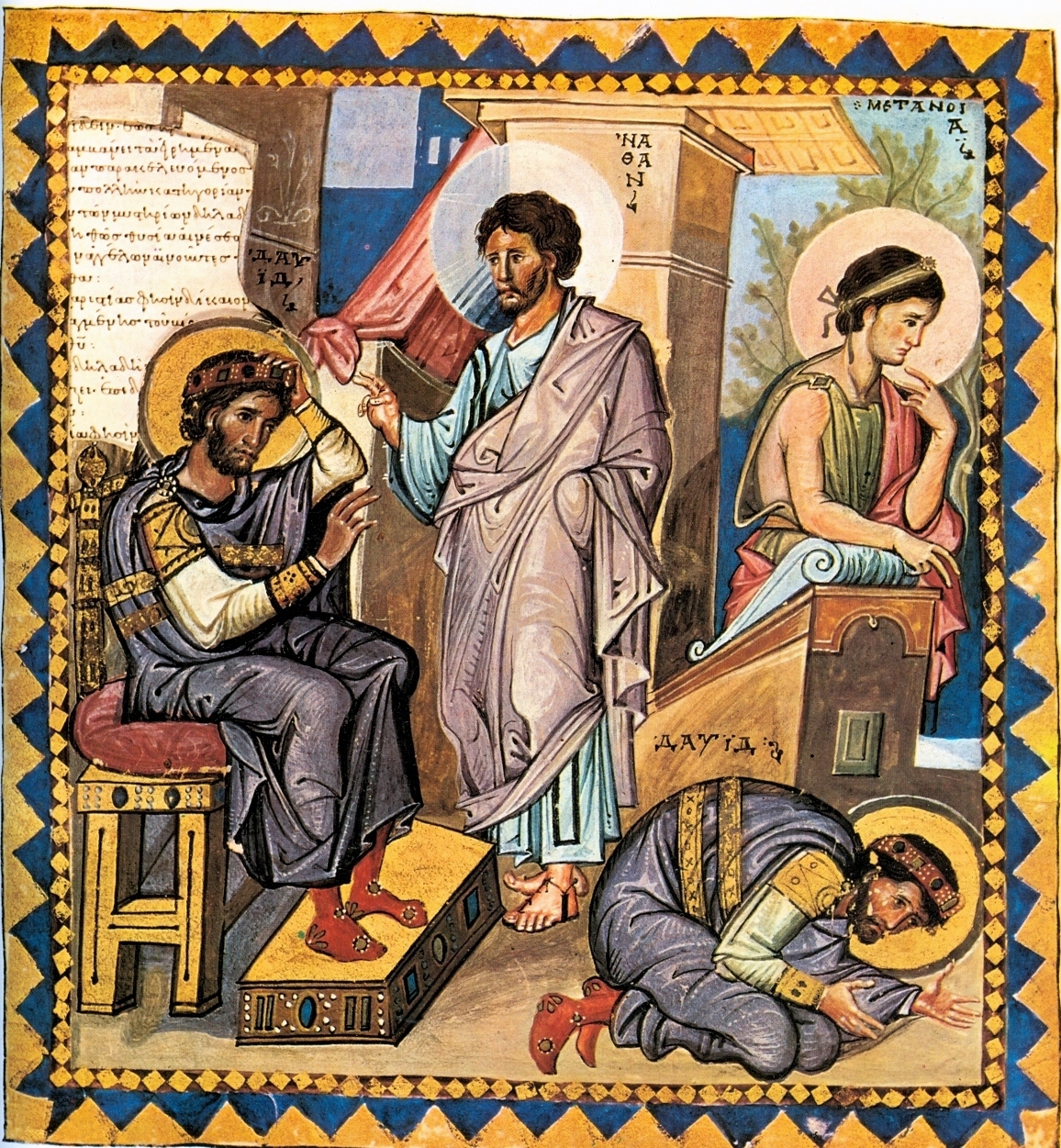

Our correspondence continued through seventeen letters over five years. My daily reach into the mailbox was an adventure. Maritain was a very modest man, never drawing attention to himself and always offering advice on how to advance my spiritual rather than my intellectual life. He urged frequent confession as good for the soul.

In 1958 I attended one year at Cardinal O’Connell minor seminary near Boston. Originally I had planned to become a monk at the Trappist Abby in Spencer, Massachusetts, but the priest in charge of vocations at the Worcester diocese persuaded me that I was too young for such a life, and that anyway I had all the makings of a secular priest (I had, and still have, no idea what that meant).

Seminary life I found alternately dull and disagreeable, perhaps mainly because I had to study Greek, Latin, and French along with English and Mathematics. Many of my fellow seminarians seemed to lack a deep spirituality. I now suspect they saw me as even more lacking. Once I was mistakenly disciplined for an infraction of the rule of silence committed by someone else in the library. I did not inform on the culprit and silently accepted a stern rebuke by the priest who was dean of discipline, a fairly disagreeable character. I met him in layman’s clothes twenty years later in an elevator. We spoke briefly, but I knew by his casual manner that he did not remember disciplining me. He had left the priesthood, married, and seemed even grumpier than I remembered him as a priest.

My family, still not churchgoers, actively opposed my decision to become a priest. After a year in the seminary, I lost the urge. There followed four years in the Air Force, during which time the letters from Maritain stopped. His wife, Raïssa, a Jewish writer and poet who had converted to Catholicism with him, had died, and he had gone to live with the Little Brothers of Jesus in Toulouse, France. One of the monks he lived with answered my last letter to Maritain, explaining that old age and illness made it necessary for him to cut back on his correspondence. Since Maritain had been a loving father figure for me, I was truly hurt by the loss.

After the Air Force I finished college, where I studied literature and philosophy. Most of the philosophers I read were atheists. The one I remember most is Bertrand Russell, especially his essay “Why I Am Not a Christian,” which I now believe has seduced many young would-be intellectuals who cannot see through the flippant shallowness of Russell’s logic. Like many strident young would-be scholars of the radical 60’s generation, I gradually came to think of myself as too smart to be taken in by religion. This seemed to me also the posture of my academic colleagues in the college where I later taught English and Humanities for thirty years. Having completed my Master’s Degree, I stopped going to Church.

My first wife was an atheist. She had many varied talents and seemed to enjoy pursuing all of them at the same time. After college, we were married by a Justice of the Peace. God was not mentioned during the ceremony, nor ever by either of us thereafter. During the second year of our marriage, my wife’s brother, Jack, killed himself with a shotgun blast to his head. Since I had spoken to him the day before about his drinking problem, I deduced, rightly or wrongly, that I had somehow inadvertently nudged him to pull the trigger. I helped his brother clean up the room in which some of his blood and flesh clung to the walls and the floor. Then I went into deep depression for several weeks and broke down in tears during a visit to my physician. He prescribed a long-term medication that eventually calmed me down. Yet to this day I feel obliged to tremble for Jack’s blood and the fate of my immortal soul.

Our relatively joyless marriage lasted ten years. I remained single for the next twenty years, ever remorseful that I had not tried harder to save our marriage. I could not judge whether it was my doing, or hers, or both of us who failed each other. I now suspect that the absence of God in our lives made all the difference. I hope she too has made that discovery and has at last found a big place for God in her life.

For about twenty-five years I was more a practical atheist than a militant warrior for the cause, though I once wrote a letter of support to America’s most hated atheist, Madalyn Murray O’Hair, who was later murdered by one of her atheist employees. But when two of my psychological anchors, my father and grandmother, died within three months of each other in 1990, I began to feel some vague rumblings of spirituality. After two years of soul-searching, I came to realize that the twenty-five years of my life without God had been the worst years of my life, even though I had imagined and convinced myself during that time that they were among the best.

I searched for and found my eighth grade teacher, Sister Ann Marshall of the Sisters of Mercy. She put me in touch with a Worcester priest, Father Bernard Gilgun, who was active in the Catholic Worker movement and knew Dorothy Day. Father Bernie was the kindest man I have ever known. During my first confession as a born-again Catholic, I broke down in tears at one point, and he joined his tears with mine. Before long I was enlisted by Father Bernie in the Catholic Worker movement to ladle food out for hungry patrons at the Mustard Seed kitchen in Worcester.

Now in my early fifties, I was attending the Eucharistic Adoration hour weekly and praying for guidance as to how I should spend my renewed life as a Catholic. I’ve been told it often happens to prodigal children soon after they return to God, and especially after they have taken up weekly Eucharistic Adoration, that they are greatly blessed in some very special way. That happened to me. Within three months my niece Jessica introduced me to my future wife, Louise. Louise had been reared in the Church of Christ in Hugo, Oklahoma, but had drifted away from churchgoing. Soon after we met, she told me that I was the third Catholic whom she had known and loved. I asked her if she didn’t think maybe God was trying to tell her something. About a year later she was welcomed into the Catholic Church by the same good priest who officiated at our wedding, Monsignor John Kelliher.

In 2001, after my retirement from teaching, Louise and I moved to Lubbock, Texas. Searching for a new ministry, one day in a second hand bookstore I happened to pick up a biography of my old hero, Jacques Maritain. The author mentioned Maritain’s last literary act before his death, the autographing of one of his own books for a man who had just been released from prison. Soon thereafter, for about five years, Louise and I taught RCIA and catechism classes in a state prison near Lamesa, Texas.

Now I’d like to share some thoughts about my return to the Catholic Church.

To the agnostic and to the atheist I say that any philosophy declaring the universe to be meaningless is itself meaningless, since that philosophy is part of a “meaningless” universe. We look for meaning (purpose) everywhere on our planet and in our lives. That being the case, why shouldn’t the universe itself have meaning or purpose? And why shouldn’t the only creature who can imagine a Thing greater than the universe reach out to that Thing in search of its own purpose?

I know God because there is a voice in me that tells me nothing makes sense without God to make sense of it. There is a voice in me (and whose voice could it be but God’s?) that tells me what is right and what is wrong, that makes me feel good when I do right, and feel bad when I do wrong. This conviction in me is so strong I have come to agree with Chesterton that the world is not an essay; it is a story. And if it is a story, there ought to be a storyteller; and the storyteller should not be one who specializes in the only kind of drama I have always despised… the theatre of the absurd.

The world we live in today seems to me on many levels absurd because it denies the existence of a divine story teller. The world has lost some common sense, to be sure, when it is argued by the Supreme Court that pornography cannot be defined, that the killing of life in the womb can be done with impunity, and that men should be able to marry men and women be able to marry women. Some kind of moral anchor has been pulled up, and we are tossed about in a tempest of moral relativity. The Catholic Church alone, it seems to me, still knows and teaches that common sense resides in the natural law. Catholic Christianity, attacked from all sides as the great enemy of progress, is in reality the only loyal friend left to the human race.

As to the absurd canard that only science can save the human race from itself, all the discoveries of modern science are now pushing us to the realization that the universe does have some kind of intelligent design behind it. Astronomers tell us that the universe at one time did not exist, and that it suddenly exploded into being. Carl Sagan, a scientist and atheist, said the early universe was filled with light. “Let there be light!” God said, we are told in Genesis. That image is too clever by far not to have been planted in the mind of the prophet by a Mind greater than his own thousands of years ago.

Max Born, quantum physicist, offered the following remark: “Those who say that the study of science makes a man an atheist must be rather silly.” Scientist Werner Heisenberg saw into the self-deception of “scientific” atheism: “The first gulp from the glass of natural sciences will turn you into an atheist, but at the bottom of the glass God is waiting for you.”

While I used to smugly suppose some merit in the advance of science as a way to discredit religion, this now seems to me a superficial and totally incomplete approach to life. There are too many issues that science is completely incompetent to address; not least of which are wisdom, ethics, aesthetics, politics, history, theories of knowledge, human destiny, and so forth. Science has no doubt provided some pleasures, conveniences, and comforts to many people; but it has also threatened by way of nuclear arsenals the future of life on this planet. The very mixed bag of scientific achievements has raised the question of whether science might, after all, lead as likely to Armageddon as to Utopia.

The fundamental dilemma of all atheist and agnostic thought is that it considers religion to be a neurosis, a failure of nerve. Atheists and agnostics, as Sigmund Freud often insisted, like to think that religion is wishful thinking for the immortality that is denied by the fact of death. It never occurred to me when I was an atheist that I might be the truly neurotic one. It never occurred to me to ask whether or not I was an atheist because I did not want God to exist. Nor did it ever occur to me to ask why I did not want God to exist. There is a profoundly developed answer to that question in Dr. Paul Vitz’s book, Faith of the Fatherless, which wonderfully upends Freud’s analysis of religion as a neurotic condition.

I do believe that someone, somewhere, prayed for me to overcome my atheism. I now believe that such prayers are necessary, and that they work wonders. The problem with atheism is that it cuts short the approach to God. Look at the biographies of many of the most famous atheists and you see they have chosen to deny God in their teen years, hardly a sign that the matter has been deeply explored. The ones who come back to God sometimes take decades to do so, and in most cases it only requires a little nudge here and there to make that happen. Some wait until the very end of their lives, and some return to God on their deathbeds without anyone knowing about it.

Here, briefly, is my favorite proof for the existence of God. The whole human race can be divided into two types: those who seek God, and those who flee from God. Nobody is sitting on the fence, even if they like to think they are. As Jesus succinctly put it: “He who is not with me is against me” (Matthew 12:30). Now there is no reason to seek a Thing unless you think in your gut the Thing exists. There is no reason to flee from a Thing unless you think there is a Thing from which to flee. Seeking or fleeing, we all believe in our gut that the Thing called God exists. Catholic theologians call this a dictate of the natural law. God planted in us a desire to know Him. We are free to embrace or reject that desire. But we are not justified to pretend that there is no Thing calling us to draw near, or no Thing from which we flee. Augustine said we cannot rest until we rest in Him.

Here is my second favorite proof for the existence of God. It rightly belongs to Thomas Aquinas, and is called the Prime Mover argument. This proof relies upon a willingness to believe that the universe was created by a Prime Mover. The only question to follow this concession is whether this Mover is a mindless Mover or a Person. At the very least, the Prime Mover, if it is to be regarded as a Person, must have will and intellect. That the universe once did not exist and came to exist with the Big Bang suggests very strongly that the Prime Mover willed it, or it would not have come to exist. That the universe came to exist, but is also dominated by laws that have produced not only order, but also minds (our own) capable of discerning the existence of that order, suggests intellect in the Prime Mover. As Albert Einstein put it, “I’m not an atheist and I don’t think I can call myself a pantheist. We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangements of the books, but doesn’t know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God.”

That the Prime Mover might want to have a personal relationship with his creatures is suggested by the fact that he chose to create them in the first place. If he doesn’t want personal relationships, he would not bother to make creatures who also want a personal relationship with him. I think that when Nietzsche said God is dead, he could have been talking about the impersonal God of the 18th century Deists. Yes, I believe that God is dead and pretty much forgotten today.

To followers of the world religions outside of Christianity, I say I am a Catholic because, if God exists, God must have created us for a reason that was clearly explained by Him to His prophets and to His Church. If God is truthful, God would have set up His true religion to compete successfully with all the other major religions of the world. And so He has. From one Jew in Israel, nailed to a tree, the ancient Jewish religion He (the Son of God) founded through Abraham and transformed through Himself has today gone out to well over a billion Catholics throughout the world. This is a miracle of the highest order that cannot be compared with the growth and longevity claimed by any of the other great religions.

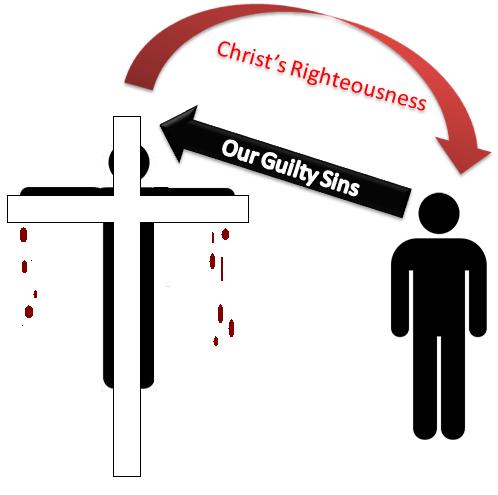

Likewise, the compassionate life and death of Jesus leaves not one doubt for me that if God is Love, there can be no greater love for humankind than the love of the God-Man who laid down His life for His friends. The religions that do not say first of all that “God is Love,” as all the early Christians said, have no appeal for me. They are at bottom either indifferent or malicious. They tend to go the way of all flesh, and if they have not gone that way yet, they eventually will.

A true religion should be the most beautiful thing on earth. I love the beauty of the Catholic Church, warts and all, above everything else. For me there is no more beautiful way to worship in all the world; surely the truest religion would be wrapped in the greatest beauty. The Catholic Mozart said it best in his sublime “Ave, verum Corpus,” his magnificent tribute to our Lord in the Eucharist. A ten-year old boy in Lubbock, Texas saw the same beauty Mozart saw when, out of half a dozen different churches, the only one he wanted to visit again was Saint Elizabeth’s.

To my Protestant friends: all Protestants surely know that the oldest of their denominations cannot trace themselves back any farther than Martin Luther. Indeed, if all Protestants of modern European descent trace their family lineage back far enough, all their ancestors at one time were Catholic. The earliest of those ancestors who were Christians in the early Church always called themselves Christians, but at some point between the third and fourth centuries they began to call themselves Catholic (Universal) Christians to distinguish themselves from those who were calling themselves Christians but had signed onto the various heresies that were spreading throughout the empire.

Protestants will also see, when they study history, that the Catholic Church produced the Nicene Creed; that it collected and authenticated the books of the New Testament; that it defended the Western world from the violent advance of Islam into Europe; that it established the hospitals and universities of Europe in the Middle Ages; and that it was a Catholic who invented the printing press and published the first Holy Bible, so that the word of God could eventually be sent by book into every home in Christendom. Wouldn’t all these marks of distinction be signs of the true Church of Christ rather than the “harlot” mentioned by Martin Luther and others? As John Henry Newman, a nineteenth century convert from the Anglican Church, said about his conversion: “To be deep in history is to cease to be Protestant.”

I invite Protestants to reflect that thousands of denominations are a clear sign that a partial truth is in them, but certainly the whole truth cannot be in all of them, since they have added to or taken away from each other’s creeds thousands of times. Thousands of denominations do not make the one Church that Christ built upon the rock called Peter; for it was a Church (not Churches) that Christ promised the gates of Hell would never prevail against (Matthew 16:18). The lack of unity among Protestant Christians has been no less dangerous to the modern world than the growing lack of unity among Catholics today. As Aesop explained in his fable of the “Bundle of Sticks,” Christians who do not stick together will be easily broken, whereas it is impossible to break a huge bundle of sticks tied together.

I regret having been an on-again, off-again Catholic, slow both in my head and in my heart to hear the words of wisdom the Holy Spirit spoke to me in my youth. Once I might have been a priest. I threw that away. Then I threw away the truth of God when I left the Church. Miserable, I walked away from my first wife to start a long and isolated journey of my own.

Recently a dear friend of mine revealed that, when we first met, he noticed that something was missing in me. I believe that was surely so, and it may still be the case. Since Adam and Eve, I suppose something has been missing in all of us. A deep hole exists, waiting for what is needed to fill it up. And so I have learned in the most painful ways possible to look for what or who is missing; for signs that come in dreams, in coincidences, in narrow escapes, in seemingly chance meetings, in all the strange and winding curves of my life; signs that the Father has spoken words of truth to a stubbornly blind and deaf child. I hope and pray that by God’s amazing grace I have at last opened my eyes and my ears that I might learn to see, to hear… and to obey.”

Love,

Matthew