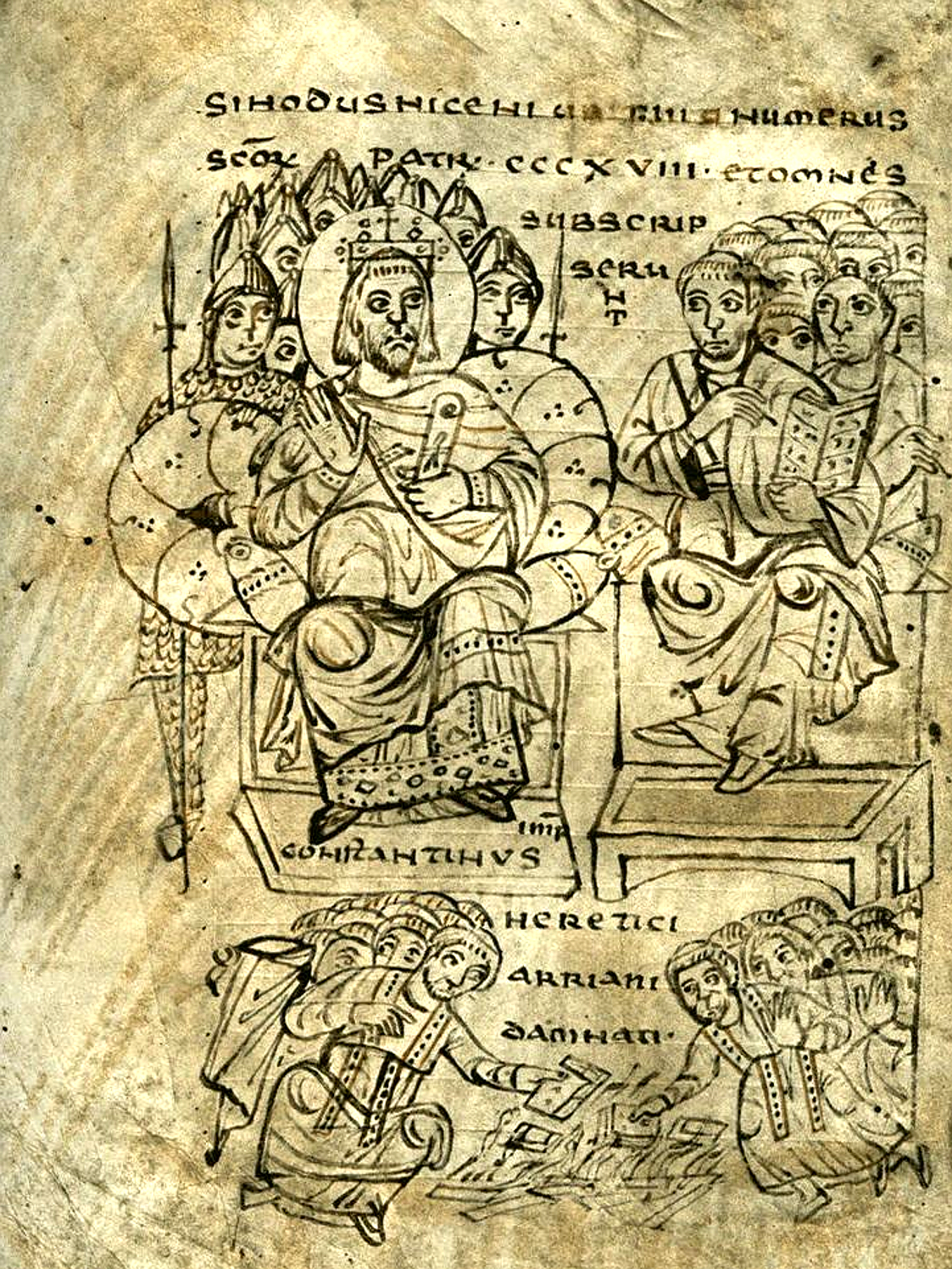

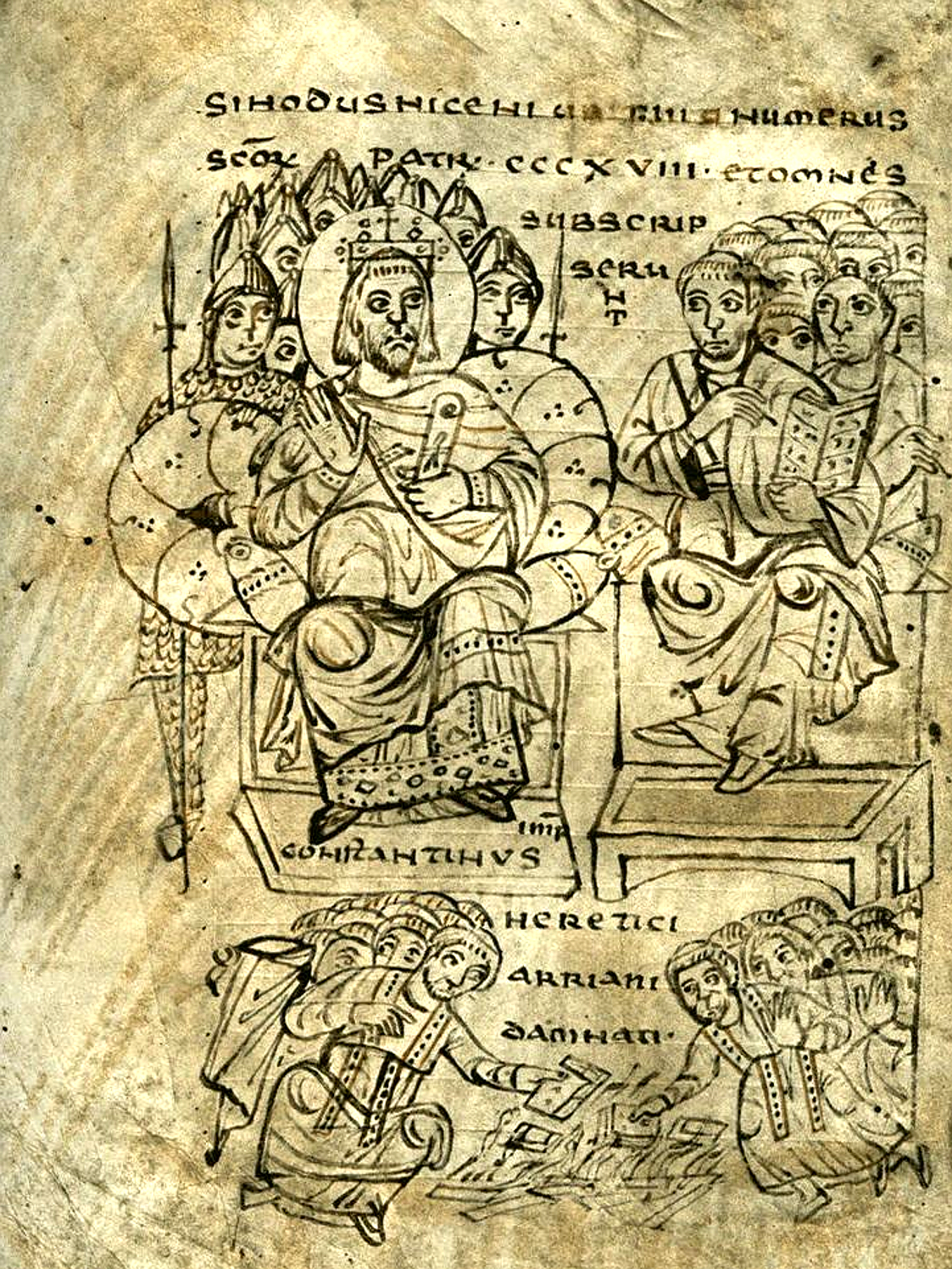

-Emporer Constantine burning Arian books, illustration from a compendium of canon law, c. 825. Drawing on vellum. From MS CLXV, Biblioteca Capitolare, Vercelli, a compendium of canon law produced in northern Italy ca. 825.

“The whole world groaned, and was astonished to find itself Arian.” – St Jerome

-by Hillaire Belloc, Chapter 3, The Great Heresies

“Arianism was the first of the great heresies.

There had been from the foundation of the Church at Pentecost A.D. 29[1] to 33 a mass of heretical movements filling the first three centuries. They had turned, nearly all of them, upon the nature of Christ.

The effect of our Lord’s predication, and Personality, and miracles, but most of all His resurrection, had been to move every one who had any faith at all in the wonder presented, to a conception of divine power running through the whole affair.

Now the central tradition of the Church here, as in every other case of disputed doctrine, was strong and clear from the beginning. Our Lord was undoubtedly a man. He had been born as men are born, He died as men die. He lived as a man and had been known as a man by a group of close companions and a very large number of men and women who had followed Him, and heard Him and witnessed His actions.

But said the Church He was also God. God had come down to earth and become Incarnate as a Man. He was not merely a man influenced by the Divinity, nor was He a manifestation of the Divinity under the appearance of a man. He was at the same time fully God and fully Man. On that the central tradition of the Church never wavered. It is taken for granted from the beginning by those who have authority to speak.

But a mystery is necessarily, because it is a mystery, incomprehensible; therefore man, being a reasonable being, is perpetually attempting to rationalize it. So it was with this mystery. One set would say Christ was only a man, though a man endowed with special powers. Another set, at the opposite extreme, would say He was a manifestation of the Divine. His human nature was a thing of illusion. They played the changes between those two extremes indefinitely.

Well, the Arian heresy was, as it were, the summing up and conclusion of all these movements on the unorthodox side that is, of all those movements which did not accept the full mystery of two natures.

Since it is very difficult to rationalize the union of the Infinite with the finite, since there is an apparent contradiction between the two terms, this final form into which the confusion of heresies settled down was a declaration that our Lord was as much of the Divine Essence as it was possible for a creature to be, but that He was none the less a creature. He was not the Infinite and Omnipotent God who must be of His nature one and indivisible, and could not (so they said) be at the same time a limited human moving and having his being in the temporal sphere.

Arianism (I will later describe the origin of the name) was willing to grant our Lord every kind of honour and majesty short of the full nature of the Godhead. He was created (or, if people did not like the word “created” then “he came forth”) from the Godhead before all other effects thereof. Through Him the world was created. He was granted one might (say paradoxically) all the divine attributes except divinity.

Essentially this movement sprang from exactly the same source as any other rationalistic movement from the beginning to our own time. It sprang from the desire to visualize clearly and simply something which is beyond the grasp of human vision and comprehension. Therefore, although it began by giving to our Lord every possible honor and glory short of the actual Godhead, it would inevitably have led in the long run into mere unitarianism and the treating of our Lord at last as a prophet and, however exalted, no more than a prophet.

As all heresies necessarily breathe the air of the time in which they arise, and are necessarily a reflection of the philosophy of whatever non-Catholic ideas are prevalent at that moment they arise, Arianism spoke in the terms of its day. It did not begin as a similar movement would begin today by making our Lord a mere man and nothing else. Still less did it deny the supernatural as a whole. The time in which it arose (the years round about A.D. 300) was a time in which all society took the supernatural for granted. But it spoke of our Lord as a Supreme Agent of God a Demiurge and regarded him as the first and greatest of those emanations of the Central Godhead through which emanations the fashionable philosophy of the day got over the difficulty of reconciling the Infinite and simple Creator with a complex and finite universe.

So much for the doctrine and for what its rationalistic tendencies would have ended in had it conquered. It would have rendered the new religion something like Mohammedanism or perhaps, seeing the nature of Greek and Roman society, something like an Oriental Calvinism.

At any rate, what I have just set down was the state of this doctrine so long as it flourished: a denial of Our Lord’s full Godhead combined with an admission of all His other attributes.

Now when we are talking of the older dead heresies we have to consider the spiritual and therefore social effects of them much more than their mere doctrinal error, although that doctrinal error was the ultimate cause of all their spiritual and social effects. We have to do this because, when a heresy has been long dead, its savour is forgotten. The particular tone and unmistakable impress which it stamped upon society being no longer experienced is non-existent for us, and it had to be resurrected, as it were, by anyone who wants to talk true history. It would be impossible, short of an explanation of this kind, to make a Catholic from Bearn today, a peasant from the neighborhood of Lourdes where Calvinism, once prevalent there, is now dead, understand the savor and individual character of Calvinism as it still survives in Scotland and in sections of the United States. But we must try to realize this now forgotten Arian atmosphere, because, until we understand its spiritual and therefore social savor, we cannot be said to know it really at all.

Further, one must understand this savour or intimate personal character of the movement, and its individual effect on society, in order to understand its importance. There is no greater error in the whole range of bad history than imagining that doctrinal differences, because they are abstract and apparently remote from the practical things of life, are not therefore of intense social effect. Describe to a Chinaman today the doctrinal quarrel of the Reformation, tell him that it was above all a denial of the doctrine of the visible church, and a denial of the special authority of its officers. That would be true. He would so far understand what happened at this Reformation as he might understand a mathematical statement. But would that make him understand the French Huguenots of today, the Prussian manner in war and politics, the nature of England and her past since Puritanism arose in this country? Would it make him understand the Orange Lodges or the moral and political systems of, say, Mr. H. G. Wells or Mr. Bernard Shaw? Of course it would not! To give a man the history of tobacco, to give him the chemical formula (if there be such a thing) for nicotine, is not to make him understand what is meant by the smell of tobacco and the effects of smoking it. So it is with Arianism. Merely to say that Arianism was what it was doctrinally is to enunciate a formula, but not to give the thing itself.

When Arianism arose it came upon a society which was already, and had long been, the one Universal Polity of which all civilized men were citizens. There were no separate nations. The Roman empire was one state from the Euphrates to the Atlantic and from the Sahara to the Scottish Highlands. It was ruled in monarchic fashion by the Commander-in-Chief, or Commanders-in-Chief, of the armies. The title for the Commander-in-Chief was “Imperator” whence we get our word Emperor and therefore we talk of that State as the “Roman Empire.” What the emperor or associated emperors (there had been two of them according to the latest scheme, each with a coadjutor, making four, but these soon coalesced into one supreme head and unique emperor) declared themselves to be, that was the attitude of the empire officially as a whole.

The emperors and therefore the whole official scheme dependent on them had been anti-Christian during the growth of the Catholic Church in the midst of Roman and Greek pagan society. For nearly 300 years they and the official scheme of that society had regarded the increasingly powerful Catholic Church as an alien and very dangerous menace to the traditions and therefore to the strength of the old Greek and Roman pagan world. The Church was, as it were, a state within a state, possessing her own supreme officials, the bishops, and her own organization, which was of a highly developed and powerful kind. She was ubiquitous. She stood in strong contrast with the old world into which she had thrust herself. What would

be the life of the one would be the death of the other. The old world defended itself through the action of the last pagan emperors. They launched many persecutions against the Church, ending in one final and very drastic persecution which failed.

The Catholic cause was at first supported by, and at last openly joined by, a man who conquered all other rivals and established himself as supreme monarch over the whole State: the Emperor Constantine the Great ruling from Constantinople, the city which he had founded and called “New Rome.” After this the central office of the Empire was Christian. By the critical date A.D. 325, not quite three centuries after Pentecost, the Catholic Church had become the official, or at any rate the Palace, Religion of the Empire, and so remained (with one very brief exceptional interval) as long as the empire stood.[2]

But it must not be imagined that the majority of men as yet adhered to the Christian religion, even in the Greek speaking East. They certainly were not of that religion by anything like a majority in the Latin speaking West.

As in all great changes throughout history the parties at issue were minorities inspired with different degrees of enthusiasm or lack of enthusiasm. These minorities had various motives and were struggling each to impose its mental attitude upon the wavering and undecided mass. Of these minorities the Christians were the largest and (what was more important) the most eager, the most convinced, and the only fully and strictly organized.

The conversion of the Emperor brought over to them large and increasing numbers of the undecided majority. These, perhaps, for the greater part hardly understood the new thing to which they were rallying, and certainly for the most part were not attached to it. But it had finally won politically and that was enough for them. Many regretted the old gods, but thought it not worth while to risk anything in their defense. Very many more cared nothing for what was left of the old gods and not much more for the new Christian fashions.

Meanwhile there was a strong minority remaining of highly intelligent and determined pagans. They had on their side not only the traditions of a wealthy governing class but they had also the great bulk of the best writers and, of course, they also had to strengthen them the recent memories of their long dominance over society.

There was yet another element of that world, separate from all the rest, and one which it is extremely important for us to understand: the Army. Why it is so important for us to understand the position of the Army will be described in a moment.

When the power of Arianism was manifested in those first years of the official Christian Empire and its universal government throughout the Graeco-Roman world, Arianism became the nucleus or centre of many forces which would be, of themselves, indifferent to its doctrine. It became the rallying point for many strongly surviving traditions from the older world: traditions not religious, but intellectual, social, moral, literary and all the rest of it.

We might put it vividly enough in modern slang by saying that Arianism, thus vigorously present in the new great discussions within the body of the Christian Church when first that Church achieved official support and became the official religion of the Empire, attracted all the “high-brows,” at least half the snobs and nearly all the sincere idealistic tories_the “die-hards”_whether nominally Christian or not. It attracted, as we know, great numbers of those who <were> definitely Christian. But it was also the rallying point of these non-Christian forces which were of such great importance in the society of the day.

A great number of the old noble families were reluctant to accept the social revolution implied by the triumph of the Christian Church. They naturally sided with a movement which they instinctively felt to be spiritually opposed to the life and survival of that Church and which carried with it an atmosphere of social superiority over the populace. The Church relied upon and was supported at the end by the masses. Men of old family tradition and wealth found the Arian more sympathetic than the ordinary Catholic and a better ally for gentlemen.

Many intellectuals were in the same position. These had not pride of family and old social traditions from the past, but they had pride of culture. They remembered with regret the former prestige of the pagan philosophers. They thought that this great revolution from paganism to Catholicism would destroy the old cultural traditions and their own cultural position.

The mere snobs, who are always a vast body in any society that is, the people who have no opinions of their own but who follow what they believe to be the honorific thing of the moment would be divided. Perhaps the majority of them would follow the official court movement and attach themselves openly to the new religion. But there would always be a certain number who would think it more “chic,” more “the thing” to profess sympathy with the old pagan traditions, the great old pagan families, the long inherited and venerable pagan culture and literature and all the rest of it. All these reinforced the Arian movement because it was destructive of Catholicism.

Arianism had yet another ally and the nature of that alliance is so subtle that it requires very careful examination. It had for ally the tendency of government in an absolute monarchy to be half afraid of emotions present in the minds of the people and especially in the poorer people: emotions which if they spread and became enthusiastic and captured the mass of the people might become too strong to be ruled and would have to be bowed to. There is here a difficult paradox but one important to be recognized.

Absolute government, especially in the hands of one man, would seem, on the surface, to be opposed to popular government. The two sound contradictory to those who have not seen absolute monarchy at work. To those who have, it is just the other way. Absolute government is the support of the masses against the power of wealth in the hands of a few, or the power of armies in the hands of a few. Therefore one might imagine that the imperial power of Constantinople would have had sympathy with the popular Catholic masses rather than with the intellectuals and the rest who followed Arianism. But we must remember that while absolute government has for its very cause of existence the defence of the masses against the

powerful few, yet it likes to rule. It does not like to feel that there is in the State a rival to its own power. It does not like to feel that great decisions may be imposed by organizations other than its own official organization. That is why even the most Christian emperors and their officials always had at the back of their minds, during the first lifetime of the Arian movement, a potential sympathy with Arianism, and that is why this potential sympathy in some cases appears as actual sympathy and as a public declaration of Arianism on their part.

There was yet one more ally to Arianism through which it almost triumphed the Army.

In order to understand how powerful such an ally was we must appreciate what the Roman Army meant in those days and of what it was composed.

The Army was, of course, in mere numbers, only a fraction of society. We are not certain what those numbers were; at the most they may have come to half a million_they were probably a good deal less. But to judge by numbers in the matter would be ridiculous. The Army was normally half, or more than half, the State. The Army was the true cement, to use one metaphor, the framework to use another metaphor, the binding force and the support and the very material self of the Roman Empire in that fourth century; it had been so for centuries before and was to remain so for further generations.

It is absolutely essential to understand this point, for it explains three-fourths of what happened, not only in the case of the Arian heresy but of everything else between the days of Marius (under whose administration the Roman Army first became professional), and the Mohammedan attack upon Europe, that is, from more than a century before the Christian era to the early seventh century. The social and political position of the Army explains all those seven hundred years and more.

The Roman Empire was a military state. It was not a civilian state. Promotion to power was through the Army. The conception of glory and success, the attainment of wealth in many cases, in nearly all cases the attainment of political power, depended on the Army in those days, just as it depends upon money-lending, speculation, caucuses, manipulation of votes, bosses and newspapers nowadays.

The Army had originally consisted of Roman citizens, all of whom were Italians. Then as the power of the Roman State spread it took in auxiliary troops, people following local chieftains, and affiliated to the Roman military system and even recruited its regular ranks from up and down the Empire in every province. There were many Gauls that is Frenchmen in the Army, many Spaniards, and so forth, before the first one hundred years of the Empire had run out. In the next two hundred years that is, in the two hundred years A.D. 100-300, leading up to the Arian heresy_the Army had become more and more recruited from what we call “Barbarians,” a term which meant not savages but people outside the strict limits of the Roman Empire. They were easier to discipline, they were much cheaper to hire than citizens were. They were also less used to the arts and comforts of civilization than the citizens within the frontiers. Great numbers of them were German, but there were many Slavs and a good many Moors and Arabs and Saracens and not a few Mongols even, drifting in from the East.

This great body of the Roman Army was strictly bound together by its discipline, but still more by its professional pride. It was a long service army. A man belonged to it from his adolescence to his middle age. No one else except the Army had any physical power. There could be no question of resisting it by force, and it was in a sense the government. Its commander-in-chief was the absolute monarch of the whole state. Now the army went solidly Arian.

That is the capital mark of the whole affair. But for the Army, Arianism would never have meant what it did. With the Army_and the Army wholeheartedly on its side_Arianism all but triumphed and managed to survive even when it represented a little more than the troops and their chief officers.

It was true that a certain number of German troops from outside the Empire had been converted by Arian missionaries at a moment when high society was Arian. But that was not the main reason that the Army as a whole went Arian. The Army went Arian because it felt Arianism to be the distinctive thing which made it superior to the civilian masses, just as Arianism was a distinctive thing which made the intellectual feel superior to the popular masses. The soldiers, whether of barbaric or civilian recruitment, felt sympathy with Arianism for the same reason that the old pagan families felt sympathy with Arianism. The army then, and especially the Army chiefs, backed the new heresy for all they were worth, and it became a sort of test of whether you were somebody_a soldier as against the despised civilians_or no. One might say that there had arisen a feud between the Army chiefs on the one hand and the Catholic bishops on the other. Certainly there was a division_an official severence between the Catholic populace in towns, the Catholic peasantry in the country and the almost universally Arian soldier; and the enormous effect of this junction between the new heresy and the Army we shall see at work in all that follows.

Now that we have seen what the spirit of Arianism was and what forces were in its favor, let us see how it got its name.

The movement for denying the full Godhead of Christ and making Him a creature took its title from one Areios (in the Latin form Arius), a Greek-speaking African cleric rather older than Constantine, and already famous as a religious force some years before Constantine’s victories and first imperial power.

Remember that Arius was only a climax to a long movement. What was the cause of his success? Two things combined. First, the momentum of all that came before him. Second, the sudden release of the Church by Constantine. To this should be added undoubtedly something in Arius’ own personality. Men of this kind who become leaders do so because they have some personal momentum from their own past impelling them. They would not so become unless there were something in themselves.

I think we may take it that Arius had the effect he had through a convergence of forces. There was a great deal of ambition in him, such as you will find in all heresiarchs. There was a strong element of rationalism. There was also in him enthusiasm for what he believed to be the truth.

His theory was certainly not his own original discovery, but he made it his own; he identified it with his name. Further, he was moved to a dogged resistance against people whom he thought to be persecuting him. He suffered from much vanity, as do nearly all reformers. On the top of all this a rather thin simplicity, “commonsense,” which at once appeals to multitudes. But he would never have had his success but for something eloquent about him and a driving power.

He was already a man of position, probably from the Cyrenaica (now an Italian colony in North Africa, east of Tripoli), though he was talked of as being Alexandrian, because it was in Alexandria that he lived. He had been a disciple of the greatest critic of his time, the martyr Lucian of Antioch. In the year 318 he was presiding over the Church of Bucalis in Alexandria, and enjoyed the high favor of the Bishop of the City, Alexander.

Arius went over from Egypt to Caesarea in Palestine, spreading his already well-known set of rationalizing, Unitarian ideas with zeal. Some of the eastern Bishops began to agree with him. It is true that the two main Syrian Bishoprics, Antioch and Jerusalem, stood out; but apparently most of the Syrian hierarchy inclined to listen to Arius.

When Constantine became the master of the whole Empire in 325, Arius appealed to the new master of the world. The great Bishop of Alexandria, Alexander, had excommunicated him, but reluctantly. The old heathen Emperor Licinius had protected the new movement.

A battle of vast importance was joined. Men did not know of what importance it was, violently though their emotions were excited. Had this movement for rejecting the full divinity of Our Lord gained the victory, all our civilization would have been other than what it has been from that day to this. We all know what happens when an attempt to simplify and rationalize the mysteries of the Faith succeeds in any society. We have before us now the ending experiment of the Reformation, and the aged but still very vigorous Mohammedan heresy, which may perhaps appear with renewed vigor in the future. Such rationalistic efforts against the creed produce a gradual social degradation following on the loss of that direct link between human nature and God which is provided by the Incarnation. Human dignity is lessened. The authority of Our Lord is weakened. He appears more and more as a man_perhaps a myth. The substance of Christian life is diluted. It wanes. What began as Unitarianism ends as Paganism.

To settle the quarrel by which all Christian society was divided, a council was ordered by the Emperor to meet, in A.D. 325, at the town of Nicaea, fifty miles from the capital, on the Asiatic side of the Straits. The Bishops were summoned to convene there from the whole Empire, even from districts outside the Empire where Christian missionaries had planted the Faith. The great bulk of those who came were from the Eastern Empire, but the West was represented, and, what was of the first importance, delegates arrived from the Primatial See of Rome; but for their adherence the decrees of the Council would not have held. As it was their presence gave full validity to these Decrees. The reaction against the innovation of Arius was so strong that at this Council of Nicaea he was overwhelmed.

In that first great defeat, when the strong vital tradition of Catholicism had asserted itself and Arius was condemned, the creed which his followers had drawn up was trampled under-foot as a blasphemy, but thespirit behind that creed and behind that revolt was to re-arise.

It re-arose at once, and it can be said that Arianism was actually strengthened by its first superficial defeat. This paradox was due to a cause you will find at work in many forms of conflict. The defeated adversary learns from his first rebuff the character of the thing he has attacked; he discovers its weak points; he learns how his opponent may be confused and into what compromises that opponent may be led. He is therefore better prepared after his check than he was at the first onslaught. So it was with Arianism.

In order to understand the situation we must appreciate the point that Arianism, founded like all heresies on an error in doctrine_that is on something which can be expressed in a dead formula of mere words soon began to live, like all heresies at their beginning, with a vigorous new life and character and savor of its own. The quarrel which filled the third century from 325 onwards for a lifetime was not after its first years a quarrel between opposing forms of words the difference between which may appear slight; it became very early in the struggle a quarrel between opposing spirits and characters: a quarrel between two opposing personalities, such as human personalities are: on the one side the Catholic temper and tradition, on the other a soured, proud temper, which would have destroyed the Faith.

Arianism learned from its first heavy defeat at Nicaea to compromise on forms, on the wording of doctrine, so that it might preserve, and spread with less opposition, its heretical spirit. The first conflict had turned on the use of a Greek word which means “of the same substance with.” The Catholics, affirming the full Godhead of Our Lord, insisted on the use of this word, which implied that the Son was of the same Divine substance as the Father; that He was of the same Being: i.e., Godship. It was thought sufficient to present this word as a test. The Arians_it was thought_would always refuse to accept the word and could thus be distinguished from the Orthodox and rejected.

But many Arians were prepared to compromise by accepting the mere word and denying the spirit in which it should be read. They were willing to admit that Christ was of the Divine essence, but not fully God; not uncreated. When the Arians began this new policy of verbal compromise, the

Emperor Constantine and his successors regarded that policy as an honest opportunity for reconciliation and reunion. The refusal of the Catholics to be deceived became, in the eyes of those who thought thus, mere obstinacy; and in the eyes of the Emperor, factious rebellion and inexcusable disobedience. “Here are you people, who call yourself the only real Catholics, prolonging and needlessly embittering a mere faction-fight. Because you have the popular names behind you, you feel yourselves the masters of your fellows. Such arrogance is intolerable.

“The other side have accepted your main point; why cannot you now settle the quarrel and come together again? By holding out you split society into two camps; you disturb the peace of the Empire, and are as criminal as you are fanatical.”

That is what the official world tended to put forward and honestly believed.

The Catholics answered: “The heretics have not accepted our main point. They have subscribed to an Orthodox phrase, but they interpret that phrase in an heretical fashion. They will repeat that Our Lord is of Divine nature, but not that he is fully God, for they still say He was created. Therefore we will not allow them to enter our communion. To do so would be to endanger the vital principle by which the Church exists, the principle of the Incarnation, and the Church is essential to the Empire and Mankind.”

At this point, there entered the battle that personal force which ultimately won the victory for Catholicism: St. Athanasius. It was the tenacity and single aim of St. Athanasius, Patriarch of Alexandria, the great Metropolitan See of Egypt, which decided the issue. He enjoyed a position of advantage, for Alexandria was the second most important town in the Eastern Empire and, as a Bishopric, one of the first four in the world. He further enjoyed popular backing, which never failed him, and which made his enemies hesitate to take extreme measures against him. But all this would not have sufficed had not the man himself been what he was.

At the time when he sat at the Council of Nicaea in 325 he was still a young man_probably not quite thirty; and he only sat there as Deacon, although already his strength and eloquence were remarkable. He lived to be seventy-six or seventy-seven years of age, dying in A.D. 373, and during nearly the whole of that long life he maintained with inflexible energy the full Catholic doctrine of the Trinity.

When the first compromise of Arianism was suggested, Athanasius was already Archbishop of Alexandria. Constantine ordered him to re-admit Arius to Communion. He refused.

It was a step most perilous because all men admitted the full power of the Monarch over Life and Death, and regarded rebellion as the worst of crimes. Athanasius was also felt to be outrageous and extravagant, because opinion in the official world, among men of social influence, and throughout the Army, upon which everything then reposed, was strong that the compromise ought to be accepted. Athanasius was exiled to Gaul, but Athanasius in exile was even more formidable than Athanasius at Alexandria. His presence in the West had the effect of reinforcing the strong Catholic feeling of all that part of the Empire.

He was recalled. The sons of Constantine, who succeeded one after the other to the Empire, vacillated between the policy of securing popular support which was Catholic_and of securing the support of the Army which was Arian. Most of all did the Court lean towards Arianism because it disliked the growing power of the organized Catholic Clergy, rival to the lay power of the State. The last and longest lived of Constantine’s sons and successors, Constantius, became very definitely Arian. Athanasius was exiled over and over again but the Cause of which he was champion was growing in strength.

When Constantius died in 361, he was succeeded by a nephew of Constantine’s, Julian the Apostate. This Emperor went over to the large surviving Pagan body and came near to reestablishing Paganism; for the power of an individual Emperor was in that day overwhelming. But he was killed in battle against the Persians and his successor, Jovian, was definitely Catholic.

However, the see-saw still went on. In 367, St. Athanasius, being then an old man of at least seventy years of age, the Emperor Valens exiled him for the fifth time. Finding that the Catholic forces were now too strong he later recalled him. By this time Athanasius had won his battle. He died as the greatest man of the Roman world. Of such value are sincerity and tenacity, combined with genius.

But the Army remained Arian, and what we have to follow in the next generations is the lingering death of Arianism in the Latin-speaking Western part of the Empire; lingering because it was supported by the Chief Generals in command of the Western districts, but doomed because the people as a whole had abandoned it. How it thus died out I shall now describe.

It is often said that all heresies die. This may be true in the very long run but it is not necessarily true within any given period of time. It is not even true that the vital principle of a heresy necessarily loses strength with time. The fate of the various heresies has been most various; and the greatest of them, Mohammedanism, is not only still vigorous but is more vigorous over the districts which it originally occupied than is its Christian rival, and much more vigorous and much more co-extensive with its own society than is the Catholic Church with our Western civilization which is the product of Catholicism.

Arianism, however, was one of those heresies which did die. The same fate has overtaken Calvinism in our own day. This does not mean that the general moral effect or atmosphere of the heresy disappears from among men, but that its creative doctrines are no longer believed in, so that its vitality is lost and must ultimately disappear.

Geneva today, for instance, is morally a Calvinist city, although it has a Catholic minority sometimes very nearly equal to half its total numbers, sometimes actually becoming (I believe) a slight majority. But there is not one man of a hundred in Geneva today who accepts Calvin’s highly defined theology. The doctrine is dead; its effects on society survive.

Arianism died in two fashions, corresponding to the two halves into which the Roman Empire_which was in those days, for its citizens, the whole civilized world fell.

The Eastern half had Greek for its official language and it was governed from Constantinople, which was also called Byzantium.

It included Egypt, North Africa, as far as Cyrene, the East Coast of the Adriatic, the Balkans, Asia Minor, Syria as far (roughly) as the Euphrates. It was in this part of the Empire that Arianism had sprung up and proved so powerful that between A.D. 300 and A.D. 400 it very nearly conquered.

The Imperial Court had wavered between Arianism and Catholicism with one momentary lapse back into paganism. But before the century was over, that is well before the year A.D. 400, the Court was definitely Catholic and seemed certain to remain so. As I explained above, although the Emperor and his surrounding officials (which I have called “the Court”) were theoretically all powerful (for the constitution was an absolute monarchy and men could not think in any other terms in those days), yet, at least as powerful, and less subject to change, was the army on which the whole of that society reposed. And the army meant the generals; the generals of the army were for the most part, and permanently, Arian.

When the central power, the Emperor and his officials, had becomevpermanently Catholic the spirit of the military was still in the mainvArian, and that is why the underlying ideas of Arianism that is, the doubt whether Our Lord was or could be really Godvsurvived after formal Arianism had ceased to be preached and accepted among the populace.

On this account, because the spirit which had underlain Arianism (the doubt on the full divinity of Christ) went on, there arose a number of what may be called “derivatives” from Arianism; or “secondary forms” of Arianism.

Men continued to suggest that there was only one nature in Christ, the end of which suggestion would necessarily have been a popular idea that Christ was only a man. When that failed to capture the official machine, though it continued to affect millions of people, there was another suggestion made that there was only one Will in Christ, not a human will and a divine will, but a single will.

Before these there had been a revival of the old idea, previous to Arianism and upheld by early heretics in Syria, that the divinity only came into Our Lord during His lifetime. He was born no more than a man, and Our Lady was the mother of no more than a man_and so on. In all their various forms and under all their technical names (Monophysites, Monothelites, Nestorians, the names of the principal three_and there were any number of others) these movements throughout the Eastern or Greek half of the Empire were efforts at escaping from, or rationalizing, the full mystery of the Incarnation; and their survival depended on the jealousy felt by the army for the civilian society round it, and on the lingering remains of pagan hostility to the Christian mysteries as a whole. Of course they depended also on the eternal human tendency to rationalize and to reject what is beyond the reach of reason.

But there was another factor in the survival of the secondary effects of Arianism in the East. It was the factor which is called today in European politics “Particularism,” that is, the tendency of a part of the state to separate itself from the rest and to live its own life. When this feeling becomes so strong that men are willing to suffer and die for it, it takes the form of a Nationalist revolution. An example of such was the feeling of the southern Slavs against the Austrian Empire which feeling gave rise to the Great War. Now this discontent of provinces and districts with the Central Power by which they had been governed increased as time went on in the Eastern Empire; and a convenient way of expressing it was to favor any kind of criticism against the official religion of the Empire. That is why great bodies in the East (and notably a large proportion of the people in the Egyptian province) favored the Monophysite heresy. It expressed their dissatisfaction with the despotic rule of Constantinople and with the taxes imposed upon them and with the promotion given to those near the court at the expense of the provincials and all the rest of their grievances.

Thus the various derivatives from Arianism survived in the Greek Eastern half of the Empire, although the official world had long gone back to Catholicism. This also explains why you find all over the East today large numbers of schismatic Christians, mainly Monophysite, sometimes Nestorian, sometimes of lesser communities, whom not all these centuries of Mohammedan oppression have been able to unite with the main Christian body.

What put an end, not to these sects, for they still exist, but to their importance, was the sudden rise of that enormous force, antagonistic to the whole Greek world_Islam: the new Mohammedan heresy out of the desert, which rapidly became a counter-religion; the implacable enemy of all the older Christian bodies. The death of Arianism in the East was the swamping of the mass of the Christian Eastern Empire by Arabian conquerors. In the face of that disaster the Christians who remained independent reacted towards orthodoxy as their one chance for survival, and that is how even the secondary effects of Arianism died out in the countries free from subjugation to the Mohammedans in the East.

In the West the fortunes of Arianism are quite different. In the West Arianism died altogether. It ceased to be. It left no derivatives tocarry on a lingering life.

The story of this death of Arianism in the West is commonly misunderstood because most of our history has been written hitherto on a misconception of what European Christian society was like in Western Europe during the fourth, fifth and sixth centuries, that is, between the time when Constantine left Rome and set up the new capital of the Empire, Byzantium, and the date when, in the early seventh century (from A.D. 633 onwards), the Mohammedan invasion burst upon the world.

What we are commonly told is that the Western Empire was overrun by savage tribes called “Goths” and “Visigoths” and “Vandals” and “Suevi” and “Franks” who “conquered” the Western Roman Empire that is, Britain and Gaul and the civilized part of Germany on the Rhine and the upper Danube, Italy, North Africa, and Spain.

The official language of all this part was the Latin language. The Mass was said in Latin, whereas in most of the Eastern Empire it was said in Greek. The laws were in Latin, and all the acts of administration were in Latin. There was no barbarian conquest, but there was a continuation of what had been going on for centuries, an infiltration of people from outside the Empire into the Empire because within the Empire they could get the advantages of civilization. There was also the fact that the army on which everything depended was at last almost entirely recruited from barbarians. As society gradually got old and it was found difficult to administer distant places, to gather the taxes from far away into the central treasury, or to impose an edict over remote regions, the government of those regions tended to be taken over more and more by the leading officers of the barbarian tribes, who were now Roman soldiers; that is, their chieftains and leaders.

In this way were formed local governments in France and Spain and even Italy itself which, while they still felt themselves to be a part of the Empire, were practically independent.

For instance, when it became difficult to govern Italy from so far off as Constantinople, the Emperor sent a general to govern in his place and when this general became too strong he sent another general to supersede him. This second general (Theodoric) was also, like all the others, a barbarian chief by birth, though he was the son of one who had been taken into the Roman service and had himself been brought up at the Court of the Emperor.

This second general became in his turn practically independent.

The same thing happened in southern France and in Spain. The local generals took over power. They were barbarian chiefs who handed over this power, that is, the nominating to official posts and the collecting of taxes, to their descendants.

Then there was the case of North Africa_what we call today Morocco, Algiers and Tunis. Here the quarrelling factions, all of which were disconnected with direct government from Byzantium, called in a group of Slav soldiers who had migrated into the Roman Empire and had been taken over as a military force. They were called the Vandals; and they took over the government of the province which worked from Carthage.

Now all these local governments of the West (the Frankish general and his group of soldiers in northern France, the Visi-gothic one in southern France and Spain, the Burgundian one in southeastern France, the other Gothic one in Italy, the Vandal one in North Africa) were at issue with the official government of the Empire on the point of religion. The Frankish one in north-eastern France and what we call today, Belgium, was still pagan. All the others were Arian.

I have explained above what this meant. It was not so much a doctrinal feeling as a social one. The Gothic general and the Vandal general who were chiefs over their own soldiers felt it was grander to be Arians than to be Catholics like the mass of the populace. They were the army; and the army was too grand to accept the general popular religion. It was a feeling very much like that which you may see surviving in Ireland still, in places, and which was universal there until quite lately: a feeling that “ascendency” went properly with anti-Catholicism.

Since there is no stronger force in politics than this force of social superiority, it took a very long time for the little local courts to drop their Arianism. I call them little because, although they collected taxes from very wide areas, it was merely as administrators. The actual numbers were small compared with the mass of the Catholic population.

While the governors and their courts in Italy and Spain and Gaul and Africa still clung with pride to their ancient Arian name and character, two things, one sudden, the other gradual, militated against both their local power and their Arianism.

The first, sudden, thing was the fact that the general of the Franks who had ruled in Belgium conquered with his very small force another local general in northern France_a man who governed a district lying to the west of him. Both armies were absurdly small, each of about 4,000 men; and it is a very good example of what the times were like that the beaten army, after the battle, at once joined the victors. It also shows what times were like that it seemed perfectly natural for a Roman general commanding no more than 4,000 men to begin with, and only 8,000 men after the first success, to take over the administration_taxes, courts of law and all the imperial forms_over a very wide district. He took over the great mass of northern France just as his colleagues, with similar forces, took over official action in Spain and Italy and elsewhere.

Now it so happened that this Frankish general (whose real name we hardly know, because it has come down to us in various distorted forms, but best known as “Clovis”) was a pagan: something exceptional and even scandalous in the military forces of the day when nearly all important people had become Christians.

But this scandal proved a blessing in disguise to the Church, for the man Clovis being a pagan and never having been Arian, it was possible to convert him directly to Catholicism, the popular religion; and when he had accepted Catholicism he at once had behind him the whole force of the millions of citizens and the organized priesthood and Bishoprics of the Church. He was the one popular general; all the others were at issue with their subjects. He found it easy to levy great bodies of armed men because he had popular feeling with them. He took over the government of the Arian generals in the South, easily defeating them, and his levies became the biggest of the military forces in the Western Latin-speaking Empire. He was not strong enough to take over Italy and Spain, still less Africa, but he shifted the centre of gravity away from the decaying Arian tradition of the Roman army now no more than small dwindling groups.

So much for the sudden blow which was struck against Arianism in the West. The gradual process which hastened the decay of Arianism was of a different kind. With every year that passed it was becoming, in the decay of society, more and more difficult to collect taxes, to keep up a revenue, and therefore to repair roads and harbors and public buildings and keep order and do all the rest of public work.

With this financial decay of government and the social disintegration accompanying it the little groups who were nominally the local governments, lost their prestige. In, say, the year 450 it was a fine thing to be an Arian in Paris or Toledo or Carthage or Arles or Toulouse or Ravenna; but 100 years later, by say, 550, the social prestige of Arianism had gone. It paid everybody who wanted to “get on” to be a Catholic; and the dwindling little official Arian groups were despised even when they acted savagely in their disappointment, as they did in Africa. They lost ground.

The consequence was that after a certain delay all the Arian governments in the West either became Catholic (as in the case of Spain) or, as happened in much of Italy and the whole of North Africa, they were taken over again by the direct rule of the Roman Empire from Byzantium.

This last experiment did not continue long. There was another body of barbarian soldiers, still Arian, who came in from the north-eastern provinces and took over the government in northern and central Italy and shortly afterwards the Mohammedan invasion swept over North Africa and ultimately over Spain and even penetrated into Gaul. Direct Roman administration, so far from surviving Western Europe, died out. Its last effective existence in the South was swamped by Islam. But long before this happened Arianism in the West was dead.

This is the fashion in which the first of the great heresies which threatened at one moment to undermine and destroy the whole of Catholic society disappeared. The process had taken almost 300 years and it is interesting to note that so far as doctrines are concerned, about that space of time, or a little more, sufficed to take the substance out of the various main heresies of the Protestant Reformers.

They, too, had almost triumphed in the middle of the sixteenth century, when Calvin, their chief figure, all but upset the French monarchy. They also had wholly lost their vitality by the middle of the nineteenth, 300 years.

ENDNOTES

1. For the discussion on the date of the Crucifixion, Resurrection and Pentecost I must refer my readers to Dr. Arendzen’s clear and learned work, “Men and Manners in the time of Christ” (Sheed and Ward). From the evidence, which has been fully examined, it is clear that the date is not earlier than 29 A.D., and may possibly be a few years later, while the most widely accepted traditional date is 33 A. D.

2. It is not easy to establish the exact point after which the Official Religion of the Roman State, or even of the Empire, is Christian. Constantine’s victory at the Milvian bridge was in the autumn of 312. The Edict of Milan, issued by himself and Licinius, which gave toleration to the practice of the Christian religion throughout the Empire, was issued early in the following year, 313. When Constantine had become the sole Emperor he soon lived as a Catechumen of the Christian Church, yet he remained head of the old Pagan religious organization as Pontifex Maximus. He was not baptized until the eve of his death, in 337. And though he summoned and presided over gatherings of Christian Bishops, they were still but a separate body in a society mainly Pagan. Constantine’s own son and successor had sympathies with the old dying Paganism. The Senate did not change for a lifetime. For active official destruction of the lingering Pagan worship men had to wait till Theodosius at the very end of the century. The whole affair covers one long human life: over eighty years.”

Love & truth,

Matthew