-please click on the image for greater detail

John Thayer Jensen was born in California in 1942 and raised in a non-religious home. At a time of emotional collapse in his life, John was influenced by several Evangelical Christians, subsequently leading to his committing his life to Christ in 1969. He eventually made his way into the Calvinist tradition, and joined a Reformed denomination in New Zealand. He converted to the Catholic faith during the Christmas season of 1995. He has a B.A. in linguistics from the University of California, Berkeley, and an M.A. in linguistics from the University of Hawaii. He lives in New Zealand, where he works at the University of Auckland and plays the horn in a local orchestra. He is also the author of a Yapese Reference Grammar and a Yapese-English Dictionary.

-John Thayer Jensen (right) & his wife, Susan (left)

Introduction

8AM Mass this morning – Father gives us a homily that takes its departure from St Paul’s “thorn in the side” to reflect on our own sufferings and trials. His homily is personal and, at points, touching. He surmises that St Paul’s “thorn” may have been some physical defect, such as poor eyesight, or perhaps a tendency to a personal fault – anger, for instance. We ourselves have our “thorns.” We should remember that God’s grace is sufficient for us; that when we are weak, then we are strong. At the end, he reminds us that Christ had, also, His “thorns” – and Father gestures at his forehead to remind us of them. Not such a bad homily, after all, but aimed at sentiment rather than thought.

The music at this, as with most of our Masses, is negligible. The content of the hymns focuses on God’s unconditional love for us; calls us to be “instruments of peace.” We usually recite the Apostle’s rather than the Nicene Creed – perhaps the latter is too long. Our response to the prayers of the faithful is to chant a Maori version of “Lord, hear our prayer” – though of Maori speakers in the congregation of perhaps 200, there may be one at most.

At our Reformed church, of which we were one of the three founding families, the sermon – 40 minutes or so, by contrast with Father’s 15-minute homily – would have been systematic and Biblical; would have explicated the text of a passage chosen by the pastor; would have related it to Reformed theological themes. The singing was always of metrical psalms – for we wished to be Biblical.

In, therefore, the manner of worship in the two churches, there is a real contrast – though not one that allows me to say this or that is better. The ordinary parish Mass can be pretty lacking in many ways; the Reformed service, on the other hand, was often dry and tedious. Still, I am not a Catholic because of ‘bells and smells.’

At the Reformed Church, once every few months those of us who were communicant members would have attended an addition to the service to celebrate the Lord’s Supper.

At Mass today, as every day, the liturgical rite to this point, the homily, the singing, are all, in a way, preface. Now the gifts of bread and wine are brought to the altar. Father prays over them, using the Church’s liturgy. “This is My Body;” “This is the chalice of My Blood.” We adore what is no longer bread and wine. We receive into our own bodies the Body and Blood of Christ.

Is it this, then, that is the reason why, 20 years after my reception into the Catholic Church, I am still a Catholic? Is this tremendous fact what compensates for the lack, in many parishes, of the “bells and smells” which some of my Protestant friends think drew me into the Church? Not exactly. Not precisely just this – the reception of Our Lord. Let me explain. Certainly it is the Eucharist that keeps me a Catholic – but it is not the Eucharist itself. I could, after all, be Orthodox. The Church – the Roman Catholic Church – assures me that the Orthodox Churches have a valid Eucharist. If I were to attend one of the dozen or so Orthodox Churches in Auckland, I would receive Him – His Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity – and I would experience a much more satisfying, beautiful, and, not to put too fine a point on it, reverent liturgy. My Orthodox friend tells me of the Divine Liturgy at the Serbian Orthodox Church. It causes my heart to long for the beauty that the Catholic Church could achieve – and does, in some Auckland parishes – approach.

It is not the Eucharist by itself that keeps me a Catholic.

I have written elsewhere of how I became a Catholic. I have been asked by (sadly few) Protestant friends which doctrine or doctrines of the Catholic Church made me a Catholic. Which Reformed teachings did I think wrong; which correct in the Catholic Church? What issue made me a Catholic?

This, I think, is to ask the wrong question. It is to put the cart before the horse; to assume that I became (and remain) a Catholic for what, at bottom, must be ideological reasons.

I became a Catholic to join the Church.

Becoming Reformed

I became a Christian on the night of Saturday 27th December, 1969 – probably, actually, early on the Sunday morning. I was 27 years old. I had had no religious experience at all before the night when, under the influence of LSD, I experienced what may be called an intellectual vision. Though I was aware of only as much of Christ as any completely secular young American may absorb from the surrounding culture, that night I knew that Jesus and the Devil were present to me, and that I could choose. I chose Jesus.

I had chosen a Christ with almost no content. I was at the time virtually without a place in the world. I was in the process of being divorced. I had dropped out of University. I was using drugs regularly. Had this not been the case, I have no doubt I would not so readily have reached out to the Hand offered me – would have been skeptical about there being any Hand at all, or anyone to extend it. I was in the position of a drowning man. Candace’s (my future wife Susan’s sister) testimony to me of her own experience was my only Christian story.

The next day I knew that I must put some content into this tiniest flickering flame of faith. I had no sort of Christian background. Susan had been brought up Anglican, but when I met her, she was not actively attending church. If she had been, it is likely I would have attended Anglican (Episcopal) worship with her. During those first weeks of 1970, I heard radio advertisements for Prince of Peace Lutheran Church’s evening youth services (complete with electric guitars). Sue and I began attending. Pastor Norman Hammer baptised me on the 26th of July, 1970. By then I was no longer a Lutheran.

By that statement, I mean that by then I was already a non-Sacramentalist. I was – albeit not very consciously – in the evangelical camp. This came about because I was being catechised by some wonderful people connected with an organisation called Campus Crusade for Christ (now called Cru). Campus Crusade is non-denominational. I do not think they would have objected if people involved with them were Catholic. Nevertheless, at least in our group, the default assumptions were evangelical; indeed, were Baptist. At no point could I have said that anyone presented me with any doctrines other than that Jesus had died for our sins, the Holy Spirit was there to help us live as we ought, and that we ought to bring others to faith in Christ.

But when, sometime after my own baptism in the Lutheran Church – perhaps around the end of 1970 – I listened to the words Pastor Hammer said in baptising a child: something along the lines of ‘God, Who has regenerated you by water and the Spirit…’ – I was shocked. I had by then read a certain amount of Lutheran theology (including much of Luther), but a greater amount of Baptist (and dispensationalist) theology. I knew, I would have said, that baptismal regeneration -was wrong. It was a form of magic. We were born again by believing. By 1971 I had persuaded Susan that we must become Baptists. We joined International Baptist Church. We were married there on 20 May, 1972. We were still members of that church on 31 January, 1973, when we left Honolulu for my first post-University job lecturing in linguistics at the University of Auckland.

In Auckland, we joined Hillsboro Baptist Church. It was near the flat we lived in. It was Baptist. But by now I was already on my way into the Reformed Church.

From the morning that I turned to Christ, I read. I read voraciously. I read the Bible through – have done about once a year since. I already knew Greek, as my degrees are in linguistics. I taught myself Hebrew. I began reading Christian writers.

John Calvin

Being in a Lutheran Church at the start, I read Luther, and Lutheran authors: Helmut Thielicke is the one I best remember. But soon, from the Campus Crusade influence, I began reading others. I read Spurgeon. I read a lot of dispensationalist authors. I read many popular writers. I read Lewis Sperry Chafer’s multi-volume Systematic Theology. I was introduced to Calvin (by Spurgeon) and read the Institutes. And I read church history – Philip Schaff’s three-volume history, a number of other works. I cannot, at this time depth, remember the names of most of the writers whose books I read.

And, slowly, I was becoming convinced that the Baptists, excellent although they were, were inadequate. In particular, their theology seemed to me simplistic; and they were so extremely clearly a very recent innovation in the history of Christianity.

For I had some independent knowledge of Christianity through historical study. I knew, in particular, that traditional Christian worship had baptised infants. The Baptists argued, of course, that this was an error. It was difficult for me to believe that almost all Christians through most of history had been wrong on this point. And I knew, as well, that Christian worship had been more … well, formal! … through most of its history.

Amongst the authors I had been reading, I especially found the writings of R. J. Rushdoony, Greg Bahnsen, Cornelius Van Til, and others in the Calvinist line convincing. Their theology was much more satisfying. I had become, by now, a Calvinist Christian. There were, of course, Calvinist Baptist churches in New Zealand. But there was a group called the Reformed Churches of New Zealand that was Calvinist, and baptised infants. The covenantal theology they taught to justify baptising infants convinced me. Sue and I began attending a Reformed Church. At the beginning of 1975 we joined the Avondale Reformed Church. When John, our first child, was born on 12 July, 1975, he was baptised there. When we left Auckland for me to work in the Education Department of the island of Yap, our official church membership remained with Avondale Reformed Church. We were members of Reformed Churches until 1995, when we left to become Catholics.

Being Reformed

I was excited about being Reformed – and I continued reading Reformed writers. I was reading van Til. Rushdoony had led me to him. Rushdoony led me also to Gary North, whose wife is Rushdoony’s daughter. And Gary North led me to Jim Jordan.

Jim Jordan was a Calvinist – at least I believe he would accept the label. However, by contrast with some more doctrinaire Calvinists, he was also interested in good thought wherever it could be found – whether amongst Protestant writers, or Orthodox, or Catholic. His own background had been Lutheran. He wrote exciting things. He seemed to think that we Calvinists had thrown out the liturgical baby when we had thrown out the legalistic bathwater of the Roman Church. He thought we ought to have Communion every Sunday. He thought baptized children should receive Communion. He thought the Reformed liturgy should look a lot like the Anglican – even, in some respects, the Catholic – liturgy.

We lived eight years in Yap. Our three other children – Helen, Eddie, and Adele – were born there. When, on our 12th wedding anniversary – 20 May, 1984 – we returned to Auckland, it was to start a Reformed Church – and I returned as an evangelist of Jim Jordan.

Reformed Church

Although my degrees are in linguistics, I have been involved in computer programming since my first year at University, in 1960. The computer was a tool for my linguistics. In Yap, in 1977, I had ordered my first personal computer. By 1980, I was doing more computing in aid of the Education Department’s needs than in relation to linguistics. And in 1980, two of my dearest friends – one now a Reformed minister – made an agreement with me, that if I moved to Pukekohe, a satellite town of Auckland, Richard would sponsor us as the nucleus of a Reformed Church. In 1983, based on my computing experience, I was offered a job as a programmer with the firm Ross then worked for in Auckland. Susan and I moved to Pukekohe. At the beginning of 1989 the Pukekohe Reformed Church was formally instituted.

I was Reformed – but I was also a disciple of Jim Jordan. I was sure that Jim was right about so much. One thing that he pressed was that communion should be a part of every Sunday’s worship. So I pressed my elders – and they agreed to move from a position of quarterly communion to bimonthly communion. Another matter that I was very hot about was the age of communion. Jim said that the qualification for receiving communion ought to be baptism. Baptism, not a certain age. But in our church in Pukekohe, to be a communicant member was to be able to vote in congregational matters. The age of Communion, said our elders, was ‘marriageable age.’

I became very upset about this. None of our children could commune. I wrote an angry letter to Session about the matter, accusing them of the ‘sin’ (my word) of withholding communion from the baptised. This event proved a turning-point in my growth. I was asked to meet with them. I was very angry. I was sure I was right and they were wrong. What they said to me had nothing to do with the question of who was right on the issue. What they did was to explain that Christ had established His Church as His agent in the world. It was up to the Church to spread the Gospel – and to govern the Kingdom. I had stated that I believed this, that I considered them, the elders of Pukekohe Reformed Church, my ‘rulers’ (Hebrews 13:17). If I wished to take the matter up, it could not begin with my accusing them of sin. It could be a matter for discussion.

In becoming members of a Reformed Church, we answer ‘I do’ to four questions in the Public Profession of Faith. The fourth is this:

“Do you promise to submit to the government of the church and also, if you should become delinquent either in doctrine or in life, to submit to its admonition and discipline?”

For the Reformed Churches of New Zealand belief in a visible Church was an essential. From a section of Church Government:

“The New Testament places a great deal of emphasis on the visible church, that is, on particular churches in each place where God is gathering His people together. The apostle Paul wrote Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 & 2 Thessalonians and the apostle John wrote letters to 7 churches in Asia Minor as dictated by Christ Himself. Our Lord Himself gave His church a procedure for dealing with sin in the congregation which makes clear that the church He is building comes to expression in visible congregations. The apostle Paul writes specific instruction to Timothy and Titus so that they might “know how one ought to conduct himself in the household of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar and support of the truth” (1 Tim. 3:15).”

All of this makes clear that the visible church and how it is run (church government) is very important to our Lord. I may not have been completely Calvinistic; I was very definitely a churchman. I was shocked. I still thought I was right about the age of Communion. But I knew they were right about the Church. I wrote a statement retracting my intention to accuse them of sin. The matter itself rather faded out after that – but I was changed. I knew that they were right about the Church.

Something Missing

From 1975 I considered myself Reformed. Yet I felt a constant sense of something missing. I longed for … I knew not what. Although I had had no Christian upbringing at all, I had, in my imaginative life, an important exposure to Catholicism. As a teenager, I had read – and been deeply moved by – Sigrid Undset’s Lavransdatter. I have never been a keen reader of historical romances, but Kristin stuck with me. When I was at University, I found it in the library and read it again – and was so moved as to read also Undset’s The Master of Hestviken. That book gave me something I had never had before: a knowledge why Christianity made such a point of Jesus’s death. Olav, the ‘Master’ of Hestviken, hurrying home to his dying wife, is in an unconsecrated church – and meditates on the meaning of Christ’s Passion.1

Jesus thought He was God, dying for the sins of men! I read this passage, and wept. I was staggered by such a conception. It did not occur to me to wonder if this could be true.

Indeed, I do not know what content I might have put into a statement: ‘this man thinks he is God.’ I only knew that I was deeply moved by this idea, by the idea of this religion – and I identified this religion with Catholicism.

Until the night I became a Christian, I had little or no exposure to any religious ideas. Providentially, after my conversion, the writer I read and returned to time and time again with a real longing was C. S. Lewis.

But Lewis was not a Catholic. Am I, perhaps, talking about Christianity in the ‘mere’ sense of Lewis’s “Mere Christianity?”

I do not think I am. The fact is that all of Lewis’s instincts are Catholic. His view of salvation as a ‘good infection’ (Mere Christianity) seems to me more akin to the idea of infused righteousness than that of the Reformed imputed righteousness. His writing is at odds with Calvinism at many points. I knew this, without really knowing how I knew it. All the 20 or so years I considered myself Reformed, I continued to read Lewis – but felt guilty doing so. I read him in secret. I would become unhappy about my Reformed worship in tears, at times – and would retire to my private office to read Lewis.

By 1991, I was thinking more and more about the Catholic-like practices: the Lord’s Supper as part of each Sunday church service, kneeling for prayer, a liturgy that more closely resembled what I thought of as Anglican but which was, really, Catholic. More accurately, my emotions were drawn more to these and similar things. Some songs that we sang before the service began – as I said above, we only used psalmody during the service itself – were translations of old Catholic hymns. One of my favourites was O Jesus Joy of Loving Hearts – a translation of St Bernard’s Jesu Dulcis Memoria.

Although this feeling is not the reason I became a Catholic – I could only become a Catholic because I believed it to be true – yet I think this emotional and instinctive feeling of missing is essential in explaining why, when I suddenly encountered the idea that Catholicism might be true, I was filled with a terrible fear – lest I be deceived – but with a great and deep joyous longing – that it might be true.

The Catholic Storm

In 1993, as part of my work as, by now, computer system administrator at the University of Auckland, I was connecting to the infant Internet. Today, the Internet is a part of everyone’s life. In 1993 it was my entry into a world I had not known existed. People from all around the world met together in this place. I discovered a Christian discussion group. There were people from all flavours of Christianity – including Catholics.

I had no conception of Catholics as … well, in truth, I had no conception of Catholics at all. My ideas were in fact simply imaginary stereotypes of one sort and another. There were Catholics here who seemed to understand the Christian faith – and to be convinced Catholics. I involved myself in one or another discussion – principally defending Catholics against Protestant misconceptions I knew not to be true.

Blessed John Henry Newman

Someone mentioned a Reformed minister who had become a Catholic. I was electrified. I had never heard of anyone becoming a Catholic. I knew of any number of examples of Catholics becoming Protestants. Who was this, I asked? The name Scott Hahn was given. Who was he? What did he write? My University library could have books of his.

‘No,’ someone said, books in the University library were unlikely. He had recorded tapes about his own conversion. If I was interested in books about Catholic converts, had I ever read Newman’s Apologia pro Vita Sua?

I had not. I had, however, heard of Newman. Newman was respectable in University circles, for he had written The Idea of a University, and University people read it, though I never had.

Francis Schaeffer had been an important early influence on me. In a taped talk of his that I had listened to, he had implied that Newman’s conversion to the Catholic Church had been dishonest. Newman had, Schaeffer had said, been exhausted by his struggles with liberalism. Newman, Schaeffer said, had wanted an infallible Church so that he would no longer need to work things out for himself. He had, in Schaeffer’s words, gone into the darkness of the Church and shut the door behind him.

I was terrified at being known to be seriously interested in Catholicism, but Newman was different. I thought of his writings as ‘serious literature.’ I went to the University library and got out Newman’s Apologia and his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. At about the same time I received, from one of the large number of kind, concerned persons in the Internet discussion group, a copy of Scott Hahn’s conversion tape, and one of Kimberley Hahn’s own story. I read both books in secret – I did not want my wife to know what I was doing! – and listened to the tapes, in my office, with earphones – instantly switching to the radio when Susan came in.

On 22nd September, 1993 – my 51st birthday – I knew I was in trouble. I had long since come to believe that many Catholic practices – such as communion as a part of every Church service – and some beliefs – such as Purgatory (which I had got from Lewis) were desirable and Biblical. As I finished reading Newman and listening to Hahn, I was horrified to find that I had come to think that the question was not what whether Reformed Christianity ought to bring back some Catholic practices and beliefs; the question was whether Jesus had in fact established a visible Kingdom on earth – and that that Kingdom might simply be the Catholic Church.

The ensuing ten months were the stormiest of my life. I have detailed something of what I experienced in the 1998 piece I referenced above. I re-read much of what I had read before in becoming, and being, Reformed. Many good people on the Internet sent me books, both for and against the Catholic Church. I consulted many on the Internet. I talked with the elder in our Reformed church who had been assigned as our family’s pastor. I talked (endlessly) with my family. I prayed. I prayed. I prayed.

Gradually, especially through reading Newman and other Catholic writers, I came to understand that the approach my Protestant – and a few Catholic – friends urged on me could not but fail. This approach was to compare the teachings of the Catholic Church with those of other Christian groups and to decide which taught the truth. In the nature of things, this could not succeed.

How was I to know which group taught the truth?

I was told I should consult the Bible. I should compare the teachings of the individual churches with what the Bible taught, and see which was most Biblical. But:

Why the Bible?

What books were the Bible?

What did the Bible teach?

The Bible is not, prima facie, a communication from God. As far back as 1985, in discussions with my Reformed pastor, I had been told that the truth and inspired character of the Bible had to be presupposed. I had to start with it; could not infer its nature from some other facts. If I did so, I was believing in myself, not in the Bible.

Further, in that same conversation, I had to presuppose the accuracy of the list of books in the Bible – in the Protestant Bible, forsooth! – in order to begin to think at all. Neither what the Bible was, nor what books constituted the Bible, were matters that could be proved from more fundamental premises. If I did so, I was believing in myself, not in God’s Word.

These considerations, nevertheless, were not of overwhelming practical importance. The contents of the Bible – at least the bulk of it, and, a decisive point, the New Testament – were agreed on by most Christians. I could start with the Bible in good company. The difficulty was with the teachings of the Bible.

For the Bible does not teach. The Bible records. People teach.

Some told me that the Sacraments were symbols only. Some told me that they were covenants that God made with me, but were not something independent of my faith in them. Some said that they were real things. For example, if I were baptised, God’s life was really made to exist in me, quite apart from my faith. Some said that there were two Sacraments, but I knew that most of Christians through most of history thought there were seven.

I was told that it was the clear teaching of Scripture that Baptism was a conscious testimony to the world of having been saved (and therefore should not be applied to infants). I was told that faith alone saved me – but that if my faith were alone – that is, did not show itself in works – that I had not truly believed.

The arguable nature of practically every Christian notion, from the very fundamental (the divinity of Christ; the personality of the Holy Spirit) to the smallest detail (must women cover their heads in Church?) cannot be doubted. All these issues are argued from the Bible. To discern the Church by its agreement with the Bible would be, in fact, to discern the Church by its agreement with my understanding of the Bible.

So I did what I had always done: I read. I re-read Van Til and Rushdoony; Luther and Calvin. I read many new books, books arguing for the truth of Catholicism and books arguing for its falsity. By June of 1994, nine months later, crisis came. I had read intensely. I had begun (in fear and trembling) attending weekday Masses at the University Newman Centre. I grew more and more terrified.

On a bus one sunny winter afternoon in June of 1994, I experienced fugue. It was not quite full loss of identity, but a terrifying state nonetheless. I had the dreadful conviction that God was determined that I must choose – and that He had determined that I would choose wrong, and be condemned for that choice. I got off the bus at a random stop. I thought I did not know where I was nor where I was going. I sat on a bench for perhaps an hour, simply trying to calm down.

In the event I did the only thing I could do: I rejected a malicious God, a God who was not only hidden but deliberately deceptive. I consciously refused to believe in such a God. If, I thought, I did my best to find the truth, either I would make the right decision, or God would lead me from there to the right decision. It was a turning point.

As it happened, Ronald Knox’s excellent book The Belief of Catholics was my freedom. Knox freed me, in particular, from the presuppositionalist trap. Speaking of the necessity of the use of ‘private judgement’ in approaching the Church, Knox says:

“Let me then, to avoid further ambiguity, give a list of certain leading doctrines which no Catholic, upon a moment’s reflection, could accept on the authority of the Church and on that ground alone.

The existence of God.

The fact that he has made a revelation to the world in Jesus Christ.

The Life (in its broad outlines), the Death, and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

The fact that our Lord founded a Church.

The fact that he bequeathed to that Church his own teaching office, with the guarantee (naturally) that it should not err in teaching.

The consequent intellectual duty of believing what the Church believes.”

That which I had begun to see in reading Newman Knox now made clear for me. Jesus left (again, in Knox’s words) not Christianity but Christendom. He left no writing; He left an authoritative body – His Body! He established a Kingdom. He fulfilled His holy people Israel, by incorporating them, with the Gentiles who would believe in His Name, into His own Body. This Body had an earthly as well as a Heavenly unity. This Body had come down to our own time. It was the Catholic Church. On a ‘plane from Wellington to Auckland at the end of July, 1994, I prayed: “Lord, I will never dot every ‘i’ or cross every ‘t.’ But I know enough to be certain that if You were to tell me I was to die tonight, I would want a priest. If You do not stop me, I am going to become a Catholic.

Coming Into Harbour

The ensuing seventeen months were characterised by frequent storms; a variety of obstacles had to be overcome. The article I referenced earlier describes this period in some detail. By late December, 1995,I had parted, in real tears and grief, with our Reformed minister, the elders, the congregation that we had been instrumental in establishing. Susan, my wife, and our four children, had all determined to enter the Catholic Church. We had gone through the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA). On the 23rd December, the day before we were to be received, the Diocese of San Francisco had judged my first marriage to be invalid (due to lack of due discretion).

That day – Saturday 23 December – we spent at the Sister’s house, making our retreat; making our first Confession (a terrifying, and, in the event, unspeakably good, experience). On Sunday morning – Christmas Eve – we affirmed:

“I believe and hold, what the Church believes and teaches.”

That confession contains, it seems to me, the essence of what it means to be a Catholic. It is not that I have sought the truth about this or that religious position, and then found that the Church agrees with me. The asymmetry of the Confession is precisely correct. It is the Church that teaches; I hold. The Church had accepted our Protestant Baptism as valid, so we were confirmed and received our first Communion. We were Catholics.

Looking Back

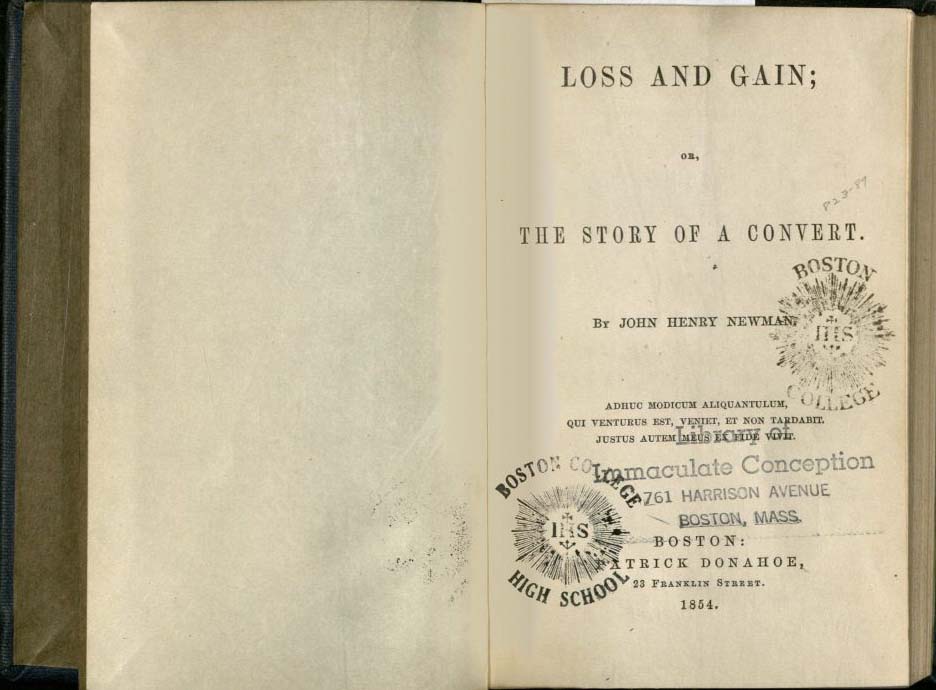

In 1848, Newman published Loss and Gain – his first publication after he was received into the Church on 9 October, 1845. In the novel, Charles Reding loses much – especially his family’s favor. In the event, the reader is told what he gained. An hour after his reception into the Church:

“[Charles] was … kneeling in the church of the Passionists before the Tabernacle, in the possession of a deep peace and serenity of mind, which he had not thought possible on earth. It was more like the stillness which almost sensibly affects the ears when a bell that has long been tolling stops, or when a vessel, after much tossing at sea, finds itself in harbor.”

I recall, with sadness, our Reformed pastor telling me, the night at the end of 1994 when I told him that I must become a Catholic, that this was yet another wild swing of my heart and mind; that within three years I would have left the Church; perhaps become a Muslim, or a Hindu. Newman, in the Apologia, concludes the history up to his reception, by writing:

“From the time that I became a Catholic, of course I have no further history of my religious opinions to narrate. In saying this, I do not mean to say that my mind has been idle, or that I have given up thinking on theological subjects; but that I have had no changes to record, and have had no anxiety of heart whatever. I have been in perfect peace and contentment. I never have had one doubt. I was not conscious to myself, on my conversion, of any difference of thought or of temper from what I had before. I was not conscious of firmer faith in the fundamental truths of revelation, or of more self-command; I had not more fervour; but it was like coming into port after a rough sea; and my happiness on that score remains to this day without interruption.”

So it has been with me. In the almost twenty years since I became a Catholic, our lives have gone through many changes. Our children have all grown up, of course, and left home. One has left the Church – indeed, for a time, struggled with belief in God, though now he is a keen Evangelical Christian. Sue and I have seven grandchildren. We are members, now, and, indeed, for the last seventeen or eighteen years, of Opus Dei, an organisation which helps us to seek holiness and sanctification in daily life. It is as difficult for me to imagine not being a Catholic as it would be for me to imagine having had different parents than I have. In John’s Gospel, Andrew and hear John Baptist refer to Jesus as the “Lamb of God.” They respond:

“And the two disciples heard what he said and followed Jesus. Jesus turned round, saw them following and said, ‘What do you want?’ They answered, ‘Rabbi’ – which means Teacher – ‘where do you live?’ He replied, ‘Come and see’; so they went and saw where he lived, and stayed with him that day. It was about the tenth hour” (John 1:38-39).”

I said above, at the end of the first section, that I had become a Catholic, not because the Church believes this or that doctrine, which I know on other grounds to be true. I became a Catholic to join the Church. I became a Catholic because that is where Jesus lives: in His Body, the Church; in the Eucharist, His Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity. I became a Catholic to join the Church.

1 ‘Meditates!’ What a bloodless word for what I experienced! For those interested, the passage is in the last chapter, chapter 15, of the second volume of the English translation of the work, beginning with the words “The snow crunched under their feet as they came outside.”

Love,

Matthew