At 49, I like to kid myself I still possess some modicum of “hipness”. I was never a hipster, really, to begin with, but, I guess, I teach them and have to try to keep the lectures, at least, mildly interesting?

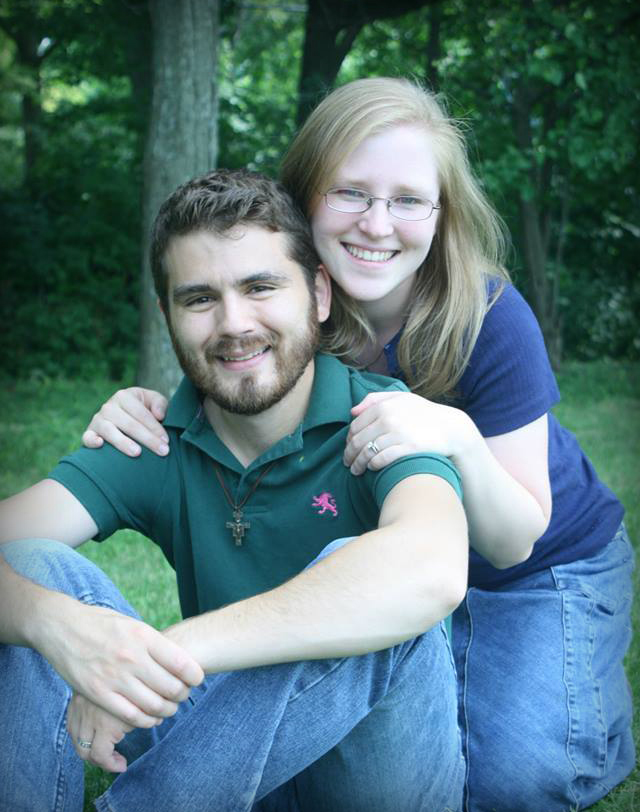

However, it does come as a shock when current, less-than-attractive fashion is pushed right onto my nose? 🙁 I have recently heard two sermons from campus ministers, who are closer to the battle, per se, than yours truly. There was so much despair. It really took my breath away. So much despair…in general, and particularly about marriage. 🙁 Young people have the meme in their heads, why bother? Why not just live for myself? Always? Why not? Why bother? Why go through the pain and the suffering of dating? The compromises of living with the other gender, whom completely DO NOT GET IT!!!!

My observation is that evil is always directly opposed to good. You know it’s evil because of this orientation. Cleverly disguised, well-marketed, slick, shiny, attractive, alluring, but a lie. Evil is always a lie; he is the father of lies. Evil NEVER tells you the Truth, that’s how you know it’s evil. Evil always tells you what you WANT to hear, but you know, in your heart-of-hearts, it is a lie. Evil HAS a feeling. It does. It damnably does. Evil NEVER entertains, even for a hair-splitting fraction of a second the possibility of the Cross. Never. That’s another way it identifies itself.

If, as Catholic theology tells us, sacraments are fountains of grace, what more appropriate means, or motivation does Evil have or need than to dissuade us from the life giving waters of grace? To be deprived of His Grace is to become the slave of sin and evil.

-by Alice Von Hildebrand

“In our society, the beauty and greatness of married love has been so obscured that most people now view marriage as a prison: a conventional, boring, legal matter that threatens love and destroys freedom.

“Love is heaven; marriage is hell,” wrote Lord Byron 150 years ago. At the time he could not have foreseen the incredible popularity that his idea would have today.

In our society the beauty and greatness or married love has been so obscured that most people now view marriage as a prison: a conventional, boring, legal matter that threatens love and destroys freedom.

My husband, Dietrich von Hildebrand was just the opposite. Long before he converted to Roman Catholicism, he was convinced that the community of love in marriage is one of the deepest sources of happiness. He saw the grandeur and the beauty of the union of spouses in marriage — symbolized by their physical union which leads in such a mysterious way to the creation of a new human person.

He recognized that love by its very essence longs for infinity and for eternity. Therefore, a person truly in love wants to bind himself forever to his beloved — which is precisely the gift that marriage gives him.

In contrast, love without an unqualified commitment betrays the very essence of love. He who refuses to commit himself (or who break a commitment in order to start another relationship) fools himself. He confuses the excitement of novelty with authentic happiness.

Such affective defeatism — so typical of our age — is a symptom or a severe emotional immaturity which weakens the very foundation of society. It is rooted partly in a misunderstanding of freedom. Many people criticize marriage because they fail to realize that a person also exercises his freedom when he freely binds himself to another in marriage.

These critics of marriage do not see that continuity — and especially faithfulness — is an essential characteristic of a truly great personality: he chooses to remain faithful to what he has seen, even though his vision may later become blurred.

In matters of love and marriage, “hell” does not come from fidelity; it comes from lack of fidelity, which leaves men technically unbound but actually solitary: trapped in a shallow arbitrariness and a stifling subjectivism.

Indeed, contrary to Lord Byron and to popular belief, marriage is the friend and protector of love between man and woman. Marriage gives love the structure, the shelteredness, the climate in which alone it can grow.

Marriage teaches spouses humility, making them realize that the human person is a very poor lover. Much as we long to love and to be loved, we repeatedly fall short and desperately need help. We must bind ourselves through sacred vows so that the bond will grant our love the strength necessary to face the tempest-tossed sea of our human condition.

For no love is free from periods of difficulties. But (as Kierkegaard aptly remarks), because it implies will, commitment, duty, and responsibility, marriage braces spouses to fight to save the precious gift of their love. It gives them the glorious confidence that with God’s help, they will overcome the difficulties and emerge victorious. Thus, by adding a formal element to the material element of love, marriage guarantees the future of love and protects it against the temptations which are bound to arise in human existence.

In a relationship without commitment, the slightest obstacle, the most insignificant difficulty is a valid excuse for separating. Unfortunately, man, who is usually so eager to win a fight over others, shows little or no desire to conquer himself. It is much easier for him to give up a relationship than to fight what Kierkegaard calls “the lassitude which often is wont to follow upon a wish fulfilled.”

Marriage calls each spouse to fight against himself for the sake of his beloved. This is why it has become so unpopular today. People are no longer willing to achieve the greatest of all victories, the victory over self.

To abolish marriage is, Kierkegaard tells us, “self- indulgence.” Only cowards malign marriage. They run from battle, defeated before the struggle even begins. Marriage alone can save love between man and woman and place it above the contingencies of daily flux and moods. Without this bond, there is no reason to wish to transform the dreariness of everyday life into a poetic song.

Sacramental marriage

In Marriage: The Mystery of Faithful Love, my husband introduced these themes which illuminate the value and importance of natural marriage and show the role that marriage plays in serving faithful love.

At the same time, my husband saw that even in the happiest of natural marriages, mortal man — the creature of a day (as Plato calls him) remains terribly finite and limited. Consequently, every merely natural love is necessarily tragic: it will never achieve the eternal union for which it naturally longs.

But when my husband converted to Catholicism, he discovered a wonderful new dimension of marriage: its sacramental character as a fountain/font of grace. St. Paul illuminated the sublime dignity of sacramental marriage in calling it a “great mystery” comparable to the love of Christ for His Church (Ephesians V: 32). Natural love pales in comparison to the beauty of a love rooted in Christ.

As a sacrament, marriage gives people the supernatural strength necessary to “fight the good fight.” Every victory achieved together over habit, routine, and boredom cements the bonds existing between the spouses and makes their love produce new blossoms.

Also, because it explicitly and sacramentally unites the spouses with the infinite love that Christ has for each one of them, sacramental marriage overcomes the tragic limits of natural marriage and achieves the infinite and eternal character to which every love aspires. It is therefore understandable that after his conversion to Roman Catholicism, my husband (who was already the great knight for natural love) became an ardent knight in defense of the supernatural love found in sacramental marriage. His enthusiasm for the great beauty and mystery of faithful love in marriage led to the writing of this work.

It is therefore understandable that after his conversion to Roman Catholicism, my husband (who was already the great knight for natural love) became an ardent knight in defense of the supernatural love found in sacramental marriage. His enthusiasm for the great beauty and mystery of faithful love in marriage led to the writing of this work.

History of marriage

The preparation of Marriage actually began in 1923 when my husband gave a lecture on marriage at a Congress of the Catholic Academic Association in Ulm, Germany. The lecture was a resounding success.

In the lecture he argued that one should distinguish between the meaning of marriage (i.e., love) and its purpose (i.e., procreation). He portrayed marriage as a community of love, which, according to an admirable divine economy, finds its end in procreation.

Even though official Catholic teaching had until then put an almost exclusive stress on the importance of procreation as the purpose of marriage, the practice of the Church had always implicitly recognized love as the meaning of marriage. She had always approved the marriage of those who, because of age or other impediments, could not enjoy the blessings of children.

But conscious that he was breaking new ground in making so explicit the distinction between the purpose and the meaning of marriage, my husband sought the approval of Church authority. So he turned to His Eminence Cardinal Pacelli, then the Papal Nuncio in Munich. To this future pope (Pius XII), my husband expounded his views, and to his joy, received from the future Pontiff a full endorsement of his position.

Cardinal Pacelli’s approval coupled with the success of the lecture on marriage encouraged my husband to expand and develop the lecture into the small volume which you now have in your hands.

Since its first publication in German, Marriage has been translated into most of the major languages of Europe, where it has never lost popularity. When it was first translated into English during World War II, critics received it very favorably and the book enjoyed great popularity, remaining in print through four editions over fourteen years.

It gives me great joy to greet this new edition, which once again makes Marriage available to English speaking readers after an absence of nearly 30 years.

Especially today, this book — revealing the sublime Christian vocation of marriage — is a must for anyone who is anxious to live worthily this great mystery of love.

Thomas a Kempis tells us that “love is a great thing.”

So is marriage.”

Love,

Matthew