“The Church is the Cross through history.

St. Paul wrote that he had determined to restrict his preaching to the Cross. (1 Cor. 2:2) This was not an effort to diminish the gospel. Rather, it was an effort to rightly understand the gospel. One of the great temptations of Christianity is to allow itself to become a “religion,” that is, to serve whatever role that religions of any sort play within a culture and the life of an individual. Despite every atheist protestation, religion abides – and if there is not one that is inherited, then a culture will invent new ones.

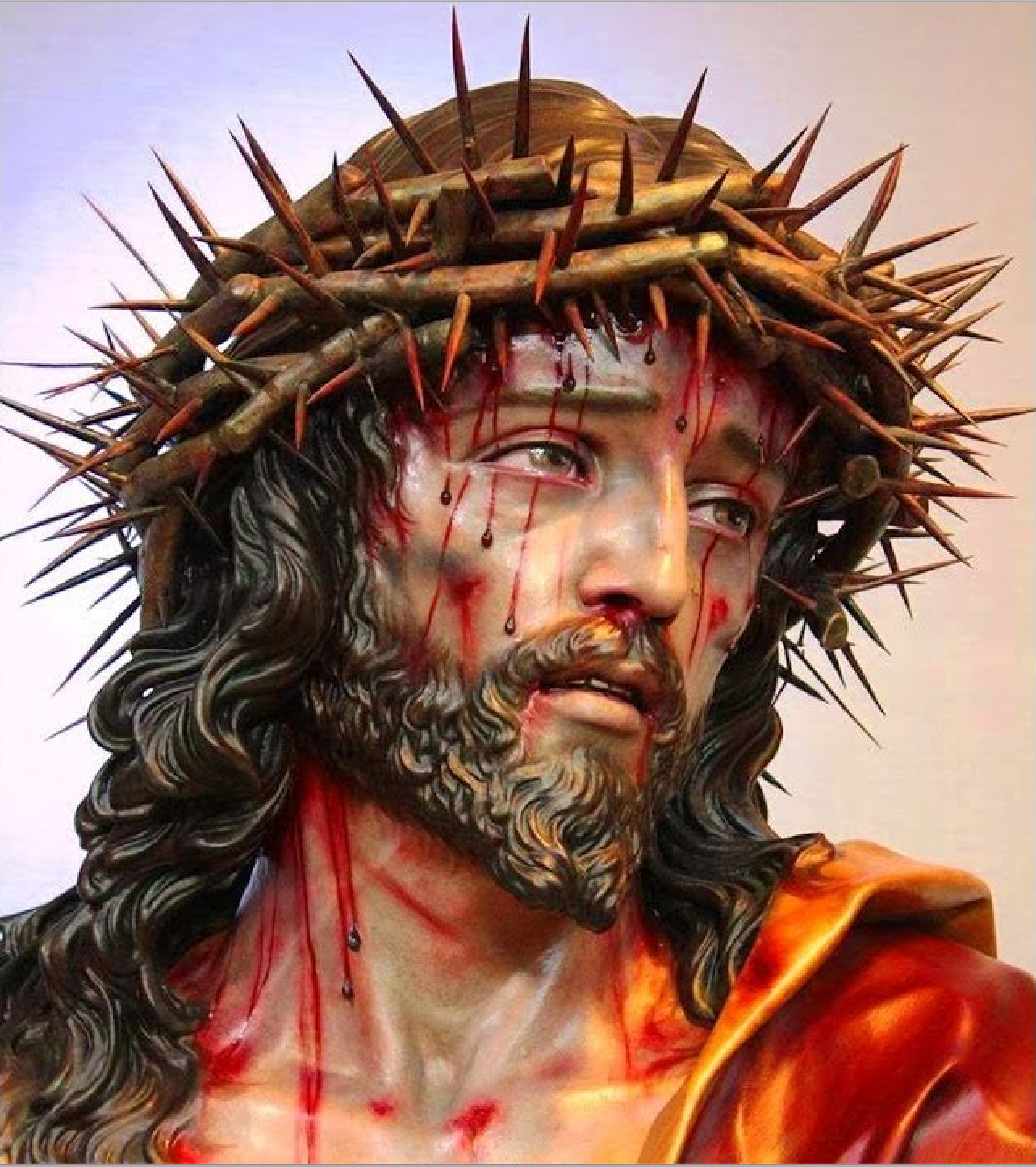

St. Paul’s concentration on the Cross – Jesus Christ crucified – was a direct affront to religion itself. To understand this, though, requires that we see the Cross for what it is. Christianity as religion reduces the Cross to a moment in time, a historical moment that is celebrated for its importance. On the Cross, Christ died for our sins. This simple statement, however, can itself be reductionist. “Christ died, I’m forgiven, now I can get on with my life.” St. Paul has something very different in mind. He says:

“I am crucified with Christ, nevertheless, I live. Yet not I, but Christ, lives in me. And the life that I now live in the flesh, I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself for me.” (Gal. 2:20)

The Cross is more than the single event in the life of Christ. It is the single event for every believer, lived moment by moment, at all times and all places. It is the very center of our being.

In Holy Baptism, we are not merely “joining the Church,” nor are we merely “washing away our sins.” Holy Baptism is not a rite of membership. Rather, Holy Baptism is being plunged into the death of Christ (Romans 6:3) and raised into the likeness of Christ’s resurrection. Believers are given a Cross to wear as part of their Baptism – a token to remind us that our new life is nothing other than living in union with the Crucified Christ.

That reality informs the commandments of Christ. We forgive our enemies because Christ forgave His enemies on the Cross (“Father, forgive them. They know not what they do.”) We share what we have with others (in the Cross we can live as though we own nothing). It represents the definition of love: “Husbands love your wives even as Christ loved the Church and gave Himself for her.” (Eph. 5:25).

It is the abandonment of the Cross (or its redefinition as “religious” event) that betrays the Church and its primary identity. It was inevitable, it seems, that the Church would eventually become the “religion of the empire.” It is a position that Christianity, in nearly every form, has endured since the 4th century. There is, of course, a critique of Christianity that its very essence was betrayed in the tolerance given by Constantine and his successors. I do not agree that the Church’s essence changed – but it would be dishonest to think that its essence was not tempted and tested. Some failed the test.

Power is an ever-present temptation in this world. It offers the notion that we can, by force (of arms or law), achieve our desired ends. That was true under emperors and tsars, and remains true within modern democracies. When Pilate questioned Jesus regarding the nature of His kingdom, Christ was very clear that His kingdom “is not of this world.” He adds that were His kingdom of this world – then His disciples would arm themselves and fight. That many Christians through the ages have imagined armed struggle to be an important element of the Christian life is a testament to our confidence in the weapons of this world and our lip-service to the Kingdom of God.

The Church is the Cross through history. The reality of the crucified life has never disappeared from among us. Before Constantine, God brought forth the movements of monasticism. While Bishops were facing the temptations of imperial blandishments, the monks and nuns were refuting every worldly option. At times, the presence of monastics created a tension within the Church. The crucified life is seen most clearly when it stands out against a background of worldliness.

I think that times of turmoil, such as we endure at present, have their own form of imperial temptation. We long for order, for normalcy, for stability. That longing can make us easy prey for the various solutions offered by the world. There is an interesting phrase in the Liturgy of St. Basil. The priest prays for God to “make the evil be good by Thy goodness.” The temptation within our hearts would likely rephrase that prayer – simply saying, “Make the evil be good.”

God has never offered us any solution other than the Cross. St. Paul readily admitted that the Cross appears to be “weakness” and “foolishness.” The Cross is a clown in a world of scholars. He nevertheless declares it to be the “wisdom and power of God.”

As we gather to recall Christ’s death on the Cross we should rightly recall the Cross within us. We should recall that the weakness and foolishness of God is the path we have been commanded to walk. If we tremble at the thought, even saying, “Let this Cup pass away from me,” then, it would seem, we will have gotten it about right.

The Church is the Cross through history. It is the only gate to Pascha’s (Easter’s) paradise.”

Love,

Matthew