-St Auguste Chapdelaine, MEP

Youngest of nine children born to Nicolas Chapdelaine and Madeleine Dodeman, 6 January 1814 at La Rochelle-Normande, France. Following grammar school, Auguste dropped out to work on the family farm. He was big and strong. He early felt a call to the priesthood, but his family opposed it, needing his help on the farm, due to his physical abilities. However, the sudden death of two of his brothers caused them to re-think, and they finally approved. He entered the minor seminary at Mortain on 1 October 1834, studying with boys half his age. It led to his being nicknamed Papa Chapdelaine, which stuck with him the rest of his life.

Ordained on 10 June 1843 at age 29. Associate pastor from 1844 to 1851, in Boucey, France. He finally obtained permission from his bishop to enter the foreign missions, and was accepted by French Foreign Missions; he was two years past their age limit, but his zeal for the missions made them approve him anyway. He stayed long enough to say a final Mass, bury his sister, and say good-bye to his family, warning them that he would never see them again. Left Paris, France for the Chinese missions on 30 April 1852, landing in Singapore on 5 September 1852.

Due to being robbed on the road by bandits, Auguste lost everything he had, and had to fall back and regroup before making his way to his missionary assignment. Chapdelaine went illegally to the Chinese interior to proselytize Christianity. The local mandarin Zhang Mingfeng was no doubt disposed to take such a harsh line against this provocation by virtue of the ongoing, Christian-inspired Taiping Rebellion, which had originated right there in Guangxi and was in the process of engulfing all of southern China in one of history’s bloodiest conflicts.

The Taiping Rebellion, 1850–64, was a revolt against the Ch’ing (Manchu) dynasty of China. It was led by Hung Hsiu-ch’üan, a visionary from Guangdong who evolved a political creed and messianic religious ideology influenced by elements of Protestant Christianity. His object was to found a new dynasty, the Taiping [great peace]. Strong discontent with the corrupt and decaying Chinese government brought him many adherents, especially among the poorer classes, and the movement spread with great violence through the E Chang (Yangtze) valley. The rebels captured Nanjing in 1853 and made it their capital.

The Western powers, particularly the British, who at first sympathized with the movement, soon realized that the Ch’ing dynasty might collapse and with it foreign trade. They offered military help and led the Ever-Victorious Army, which protected Shanghai from the Taipings. The Taipings, weakened by strategic blunders and internal dissension, were finally defeated by new provincial armies led by Tseng Kuo-fan and Li Hung-chang. Some 20 million people died in the uprising, which was filled with acts of barbarism on both sides.

St Auguste reached Kwang-si province in 1854, and was arrested in Su-Lik-Hien ten days later. He spent two to three weeks in prison, but was released, and ministered to the locals for two years, converting hundreds. In February 1856, the pagan wife of a new convert didn’t like her husband chastising her for not being more like the Christian wives he knew. She complained to her brother and uncle, who denounced St. Auguste to the local magistrate as a Christian and prosletyzing, a capital crime outside the five open ports where it was allowed, but not in the interior.

Arrested on 26 February 1856 during a government crackdown due to the Taiping Rebellion, he was returned to Su-Lik-Hien and sentenced to death for his work.

Like his Master, Fr. Chapdelaine said very little in his own defense. Furious at what he considered to be disrespect, the official had him flogged 150 times on the cheeks. The very first lash drew blood. We can only imagine what damage the other 149 blows did. Next Father received 300 lashes with a cane on his back. They stopped only when they saw he could not move.

But when they went to drag him back to his cell, after only a few steps, he rose and began walking as if in perfect health. The Chinese couldn’t believe their eyes. The saint told them, “It is the good God Who protects and blesses me.”

They next placed him in a custom made cage. His head fit through a hole in the top, and it was just tall enough for him to barely touch his toes on the ground. Furthermore the cage was constructed to hold his arms in place so that he could not use them to pull himself up in order to breath more easily. Thus he was always hovering between suffocation and barely breathing.

The mandarin offered to spare his life, however, provided he came up with a ransom of 400 silver talents. “I have no money,” he said, “only books.” What about 150 talents, then? he was asked. He replied, “Let the mandarin do what he pleases with me. I am in his hands.” Thus on February 29, 1856, they beheaded him. They needn’t have bothered, though. He had been beaten so badly and his body had been so tortured, he was already dead.

He had not sought out martyrdom. Not long before his arrest, he was reputed to have said, “He Who gives us our lives demands that we should take reasonable care of the gift. But if the danger comes to us, then happy those who are found worthy to suffer for His dear sake.” Nonetheless die he did.

Martyred at around this same time was St. Agnes Tsao Kou Ying, one of his lay catechists who had been stuck in the same sort of cage as he had been. Their cages were placed side-by-side, and while they could see one another, they could not talk. Doing so was impossible.

Also giving his life was St. Lawrence Bai Xiaoman, a layman who had promised to accompany Father to death if need be for the sake of Jesus Christ and the salvation of souls.

Learning of his death, the head of the French mission at Hong Kong sent this protest to Ye Ming-Chen, governor of Guangdong:

“The captivity of Mr. Chapdelaine, the torture he suffered, his cruel death, and the violence that was made to his body constitute, noble Imperial Commissioner, a blatant and odious violation of the solemn commitments to which he was consecrated. Your government therefore needs to give [some reparation] to France. You will not hesitate to give it me fully and entirely. You will propose the terms: I will have to then decide if the honor, dignity, and interests of the Government of my great Emperor allow me to accept. My desire is also to go to Canton and to confer in person with Your Excellency. You know an hour of friendly conversation more often than not advances the solution to important affairs than a month of written correspondence.”

The Chinese were frankly tired of the foreign powers throwing their weight around. China, after all, has always been a great and mighty nation. Were it not for the Europeans’ advanced military technology—ironically, technology that had its birth in China—China would have swatted these “bearded foreign devils” away like flies.

Thus it shouldn’t surprise us that the Chinese government refused to apologize or offer compensation or any satisfaction for the life of Fr. Chapdelaine. After all, had he not clearly broken Chinese law by breaching the interior and preaching an illegal religion? He had. And was not the punishment for this beheading? It was. So for what was there to apologize? Abbé Chapdelaine wasn’t the only French citizen arrested for such activity. At the time, six of his countrymen were in custody for attempting to spread the gospel.

Furthermore, Father’s activities took place in territory where rebels were active (Christianity-inspired Taiping Rebellion). How could it not be that a Frenchman – whose Christian government had not shown itself overly friendly or necessarily an ally to China – was doing something other than preaching religion? In fact, the Chinese viceroy asserted that Father’s activities had nothing whatsoever to do with religion. He was an agitating agent working against the government.

This turn of affairs was not necessarily disadvantageous to the French. Many of their countrymen had suffered martyrdom for their missionary work, and their government had never once taken action or retaliated. Now the sense was, “Enough is enough.” As the aforementioned minister wrote his nation’s Foreign Office:

“If, in a word, the Representative of His Imperial Majesty would not but fail in his duty if he did not take advantage of the opportunity offered him to fix with one blow the errors or mistakes of the past and to bring out of the martyrdom of a missionary the complete emancipation of Christianity [in China].”

As a result of the Chinese government’s refusal to apologize in any way, France thus used the incident as a pretext to join the United Kingdom in the Second Opium War. Britain’s purpose for the war was to have China legalize the opium trade (heroin comes from opium), expand its access to near-slave-wages Chinese labor (abuses of Chinese workers had led their government to cut off English access to such labor), and get China to exempt foreign imports from internal transit duties.

The war lasted until 1860. While it obtained for foreign missionaries access to China’s interior, all in all it was a shameful mess. One could say about it what the English politician Gladstone said about the First Opium War: “I feel in dread of the judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China…. [This is] a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace.”

Pope St. John Paul II canonized St. Auguste and other Chinese martyrs on October 1, 2000, the same day (perhaps not coincidentally) as the anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. The next day the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Daily released an article showing all the ways those canonized were actually bandits and other types of miscreants. It accused St. Auguste of raping women, of living with a woman named Cao, and of bribing officials on behalf of “bandits”.

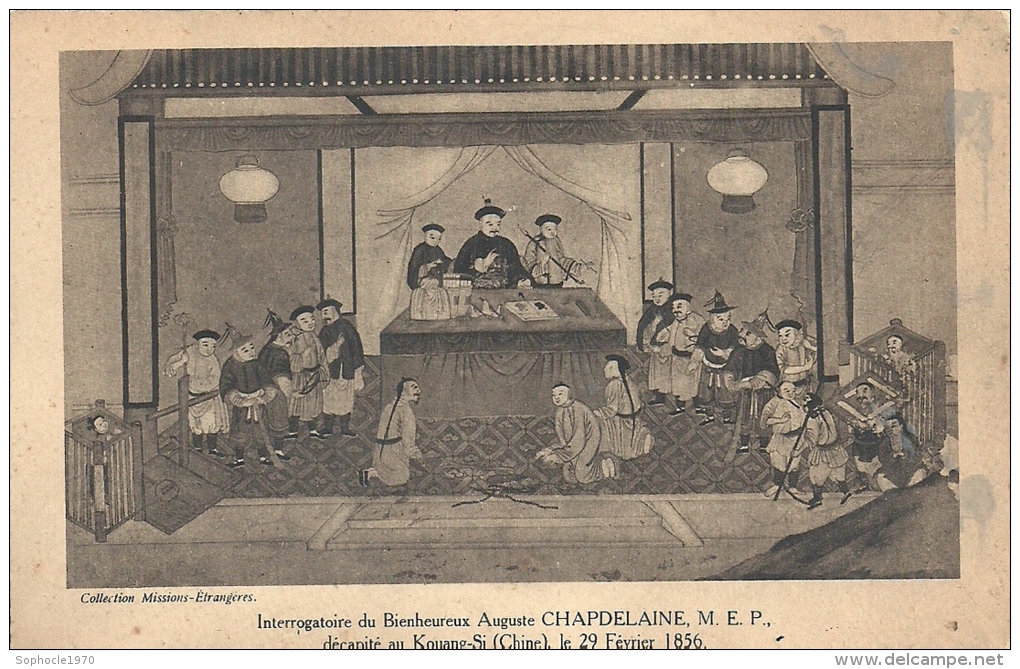

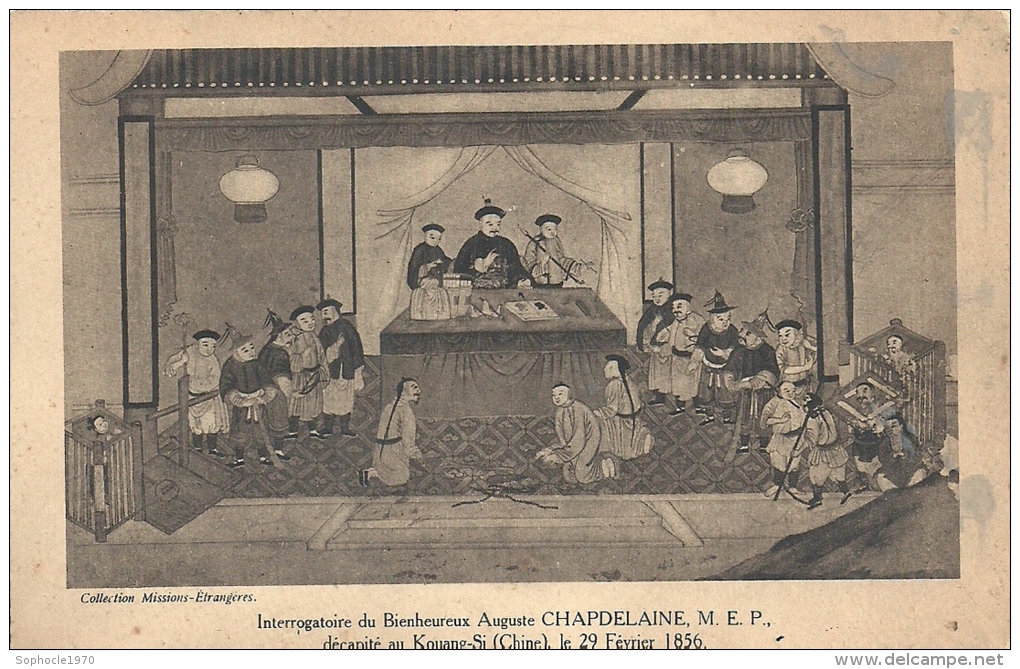

-Chapdelaine interrogation, please click on the image for greater detail.

-Chapdelaine sentencing.

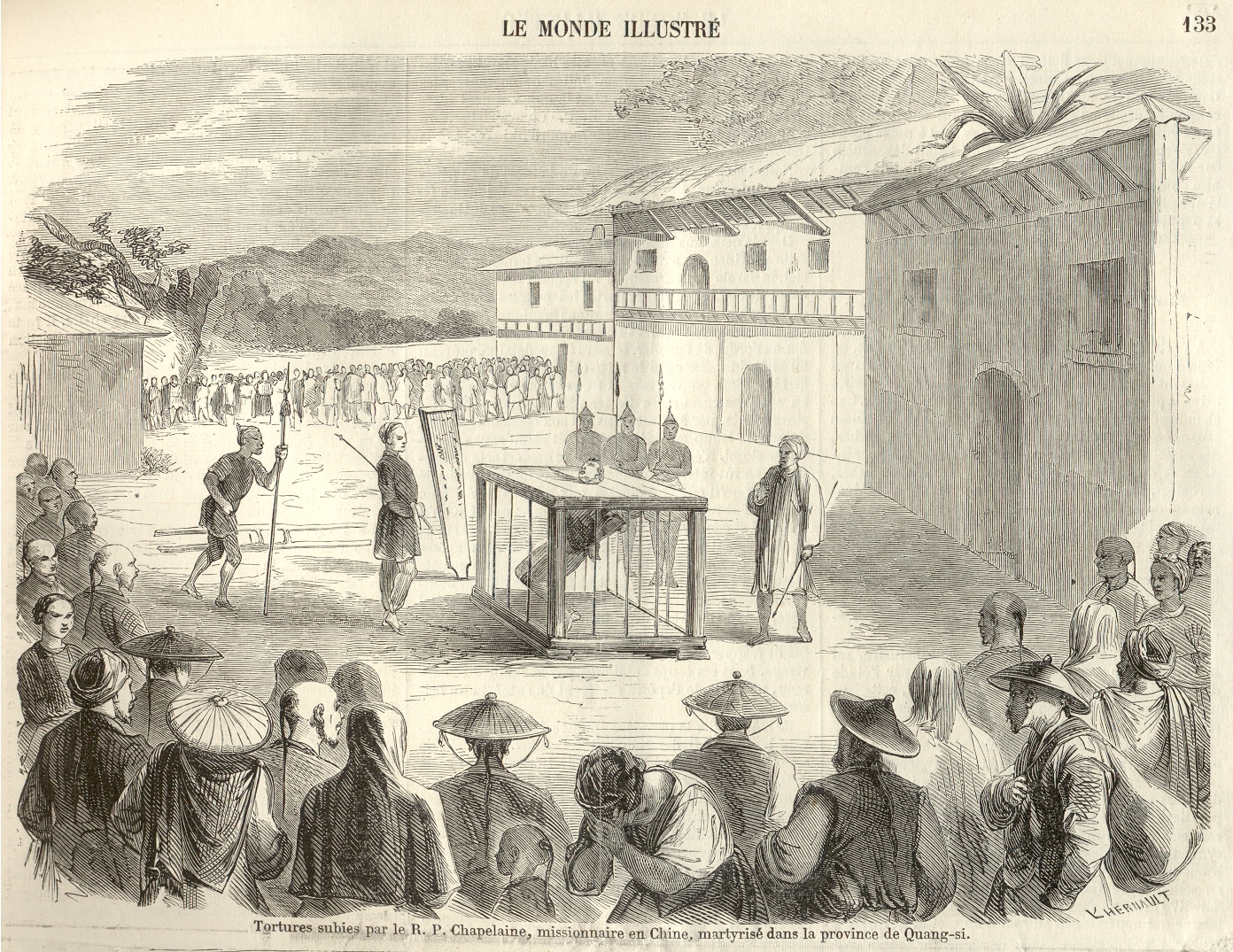

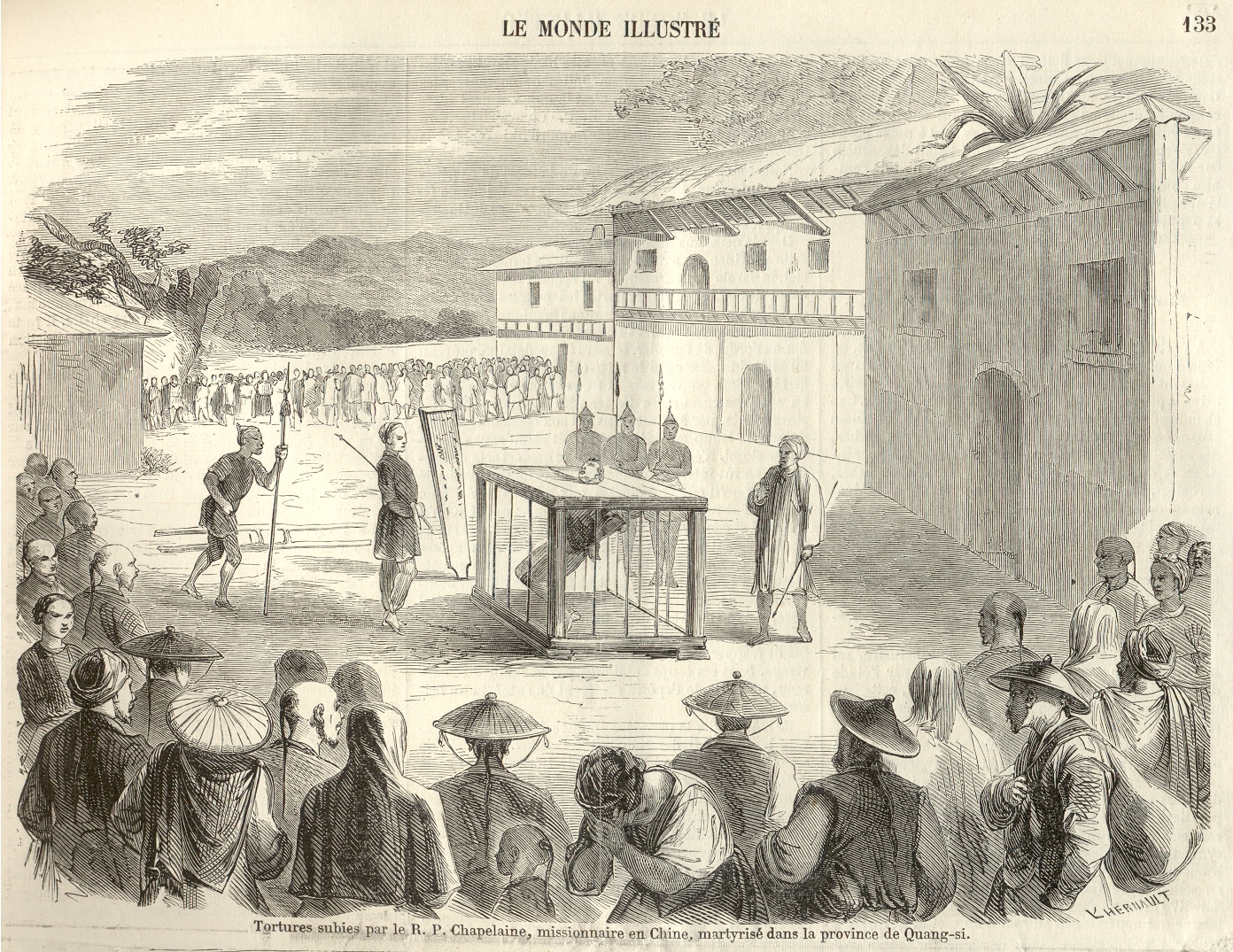

-Chinese “slow-slicing” torture, Lingchi, literally meaning “death-by-a-thousand-cuts”, an 1858 illustration from the French newspaper Le Monde Illustré, of the lingchi execution of a French missionary, Auguste Chapdelaine, in China. In fact, Chapdelaine died from physical abuse in prison, and was beheaded after death. Please click on the image for greater detail.

-Chapdelaine, further torture in a box where the victim can neither stand nor rest. If painful exertions are not made, the victim will suffocate. Please click on the image for greater detail.

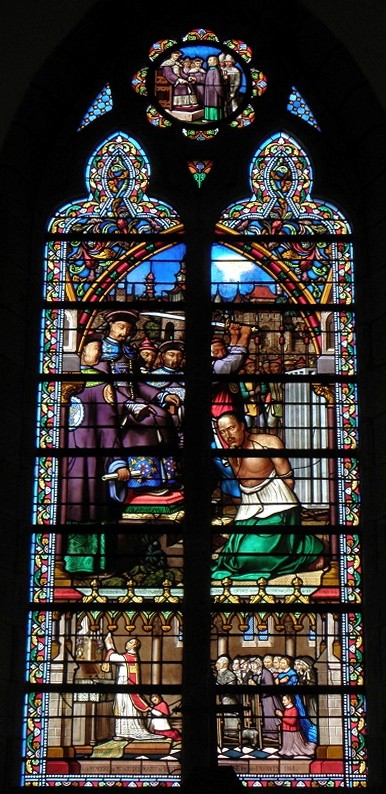

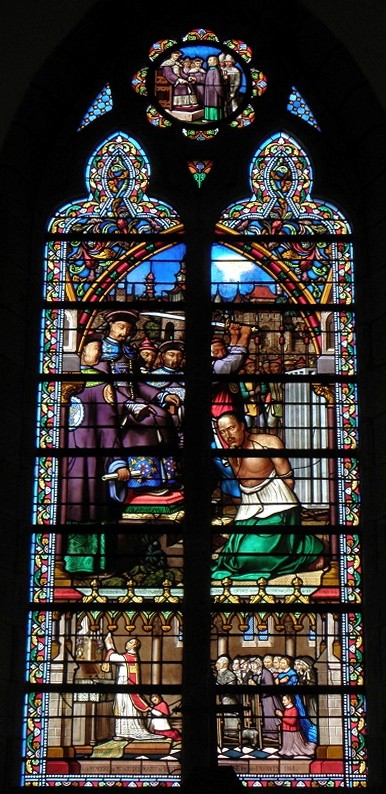

-beheading of St Auguste Chapdeline, stained glass in the parish church of Boucey, France, where he had been associate pastor.

-statue of St Auguste Chapdelaine, parish church, Boucey, France.

“I am being sent to China. You must treat this as a sacrifice made for God, and He will reward you in eternity. At your death, you shall appear before Him in confidence [and He will remember] your generosity for His greater glory in sacrificing what is dearest to you. Please sign the letter you will send me as soon as possible as sign of your consent and also as a sign of your forgiveness for all the sorrow I have caused you. And as sign of your blessing, please add a cross after your name.” -in a letter to his mother, making her aware his foreign assignment, 1852, from Paris.

“I thank God for the wonderful family He has given me and for the conduct of all its members…. It has been my greatest happiness on earth to have had such an honorable family.” -from a letter to his brother, Nicolas, at the same time, 1852.

Almighty and ever-living God, You have raised the Chinese martyrs to be models of our faith. Through Your grace, they had the courage to witness to Your Gospel by giving up their lives. May their blood continue to nourish the seeds of faith in the Chinese people, leading them to know and love You. We ask this through our Lord, Jesus Christ, Your Son, Who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Love,

Matthew