Edmund Campion, to the Learned Members of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, Greeting.

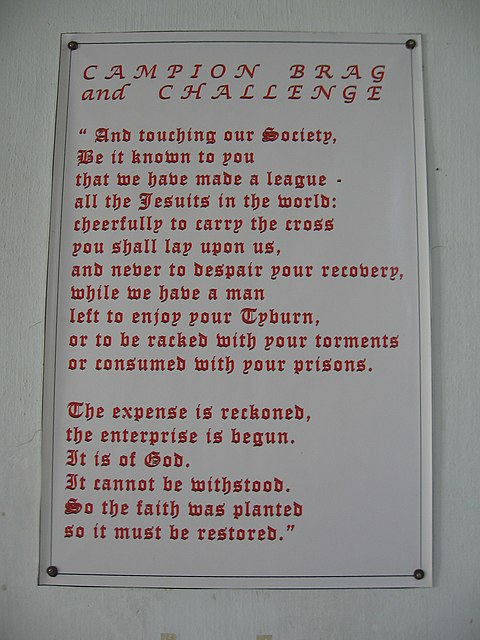

Last year, Gentlemen, when in accordance with my calling in life I returned under orders to this Island, I found on the shore of England not a little wilder waves than those I had recently left behind in the British Seas. As thereupon I made my way into the interior of England, I had no more familiar sight than that of unusual executions, no greater certainty than the uncertainty of threatening dangers. I gathered my wits together as best I could, remembering the cause which I was serving and the times in which I lived. And lest I might perhaps be arrested before I had got a hearing from any one, I at once put my purpose in writing, stating who I was, what was my errand, what war I thought of declaring and upon whom. I kept the original document on my person, that it might be taken with me, if I were taken. I deposited a copy with a friend, and this copy, without my knowledge, was shown to many. Adversaries took very ill the publication of the paper. What they particularly disliked and blamed was my having offered to hold the field alone against all comers in this matter of religion, though to be sure I should not have been alone had I disputed under a public safe conduct. Hanmer and Chartres have replied to my demands. What is the tenour of their reply? All off the point. The only honest answer for them to give is one they will never give: “We embrace the conditions, the Queen pledges her word, come at once.” Meanwhile they fill the air with their cries: “Your conspiracy! your seditious proceedings! your arrogance! traitor! aye marry, traitor!” The whole thing is absurd. These men are not fools: why are they wasting their pains and damaging their own reputation?

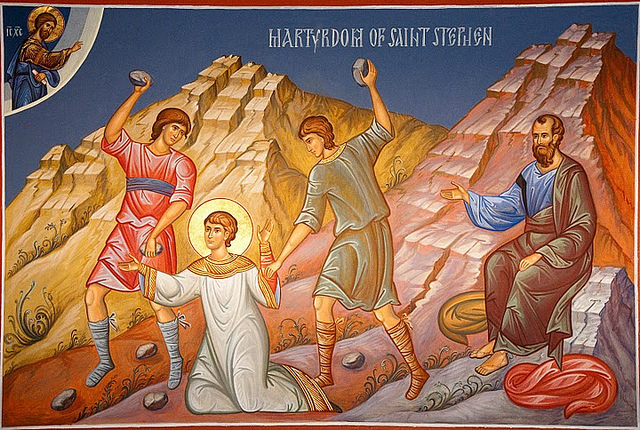

Nevertheless, in reply to these two gentlemen (one of whom has chosen my paper to run at for his amusement, the other more maliciously has confused the whole issue) there has recently been presented a very clear memorial setting forth all that need be said about our Society and their calumnies and the part that we are taking. The only course left open to me (since as I see, it is tortures, not academic disputations, that the high-priests are making ready) was to make good to you the account of my conduct; to show you the chief heads and point my finger to the sources from whence I derive this confidence; to exhort you also, as it is your concern above others, to give to this business that attention which Christ, the Church, the Common Weal, and your own salvation demand of you. If it were confidence in my own talents, erudition, art, reading, memory, that led me to challenge all the skill that could be brought against me, then were I the vainest and proudest of mortals, not having considered either myself or my opponents. But if, with my cause before my eyes, I thought myself competent to show that the sun here shines at noon-day, you ought to allow in me that heat which the honour of Jesus Christ, my King, and the unconquered force of truth have put upon me. You know how in Marcus Tullius’s speech for Publius Quintius, when Roscius promised that he should win the case if he could make out by arguments that a journey of 700 miles had not been accomplished in two days, Cicero not only had no fear of all the force of the pleading of the opposing counsel, Hortensius, but could not have been afraid even of greater orators than Hortensius, men of the stamp of Cotta and Antonius and Crassus, whose reputation for speaking he set higher than that of all other men: for truth does sometimes stand out in so clear a light that no artifice of word or deed can hide it. Now the case on our side is clearer even than that position of Roscius. I have only to evince this, that there is a Heaven, that there is a God, that there is a Faith, that there is a Christ, and I have gained my cause. Standing on such ground should I not pluck up heart? I may be killed, beaten I cannot be. I take my stand on those Doctors, whom that Spirit has instructed who is neither deceived nor overcome.

I beg of you, consent to be saved. Of those from whom I obtain this consent I expect without the least doubt that all the rest will follow. Only give yourselves up to take interest in this inquiry, entreat Christ, add efforts of your own, and certainly you will perceive how the case lies, how our adversaries are in despair, and ourselves so solidly founded that we cannot but desire this conflict with serene and high courage. I am brief here, because I address you in the rest of my discourse. Farewell.

“I will give you a mouth and wisdom, which all your adversaries shall not be able to resist and gainsay.” Luc. 21. 15.

1. Holy Writ.

2. The Sense of Holy Writ.

3. The Nature of the Church.

4. Councils.

5. Fathers.

6. The Grounds of Argument Assumed by the Fathers.

7. History.

8. Paradoxes.

9. Sophism.

10. All Manner of Witness.

Of the many signs that tell of the adversaries’ mistrust of their own cause, none declares it so loudly as the shameful outrage they put upon the majesty of the Holy Bible. After they have dismissed with scorn the utterances and suffrages of the rest of the witnesses, they are nevertheless brought to such straits that they cannot hold their own otherwise than by laying violent hands on the divine volumes themselves, thereby showing beyond all question that they are brought to their last stand, and are having recourse to the hardest and most extreme of expedients to retrieve their desperate and ruined fortunes. What induced the Manichees to tear out the Gospel of Matthew and the Acts of the Apostles? Despair. For these volumes were a torment to men who denied Christ’s birth of a Virgin, and who pretended that the Spirit then first descended upon Christians when their peculiar Paraclete, a good-for-nothing Persian, made his appearance. What induced the Ebionites to reject all St. Paul’s Epistles? Despair. For while those Letters kept their credit, the custom of circumcision, which these men had reintroduced, was set aside as an anachronism. What induced that crime-laden apostate Luther to call the Epistle of James contentious, turgid, arid, a thing of straw, and unworthy of the Apostolic spirit? Despair. For by this writing the wretched man’s argument of righteousness consisting in faith alone was stabbed through and rent assunder. What induced Luther’s whelps to expunge off-hand from the genuine canon of Scripture, Tobias, Ecclesiasticus, Maccabees, and, for hatred of these, several other books involved in the same false charge? Despair. For by these Oracles they are most manifestly confuted whenever they argue about the patronage of Angels, about free will, about the faithful departed, about the intercession of Saints.

Is it possible? So much perversity, so much audacity? After trampling underfoot Church, Councils, Episcopal Sees, Fathers, Martyrs, Potentates, Peoples, Laws, Universities, Histories, all vestiges of Antiquity and Sanctity, and declaring that they would settle their disputes by the written word of God alone, to think that they should have emasculated that same Word, which alone was left, by cutting out of the whole body so many excellent and goodly parts! Seven whole books, to ignore lesser diminutions, have the Calvinists cut out of the Old Testament. The Lutherans take away the Epistle of James besides, and, in their dislike of that, five other Epistles, about which there had been controversy of old in certain places and times. To the number of these the latest authorities at Geneva add the book of Esther and about three chapters of Daniel, which their fellow-disciples, the Anabaptists, had some time before condemned and derided.

How much greater was the modesty of Augustine (“De doct. Christ. lib.” 2, c. 8.), who, in making his catalogue of the Sacred Books, did not take for his rule the Hebrew Alphabet, like the Jews, nor private judgment, like the Sectaries, but that Spirit wherewith Christ animates the whole Church. The Church, the guardian of this treasure, not its mistress (as heretics falsely make out), vindicated publicly in former times by very ancient Councils this entire treasure, which the Council of Trent has taken up and embraced. Augustine also in a special discussion on one small portion of Scripture cannot bring himself to think that any man’s rash murmuring should be permitted to thrust out of the Canon the book of Wisdom, which even in his time had obtained a sure place as a well-authenticated and Canonical book in the reckoning of the Church, the judgment of ages, the testimony of ancients, and the sense of the faithful. What would he say now if he were alive on earth, and saw men like Luther and Calvin manufacturing Bibles, filing down Old and New Testament with a neat pretty little file of their own, setting aside, not the book of wisdom alone, but with it very many others from the list of Canonical Books? Thus whatever does not come out from their shop, by a mad decree, is liable to be, spat upon by all as a rude and barbarous composition.

They who have stooped to this dire and execrable way of saving themselves surely are beaten, overthrown, and flung rolling in the dust, for all their fine praises that are in the mouths of their admirers, for all their traffic in priesthoods, for all their bawling in pulpits, for all their sentencing of Catholics to chains, rack and gallows. Seated in their armchairs as censors, as though any one had elected them to that office, they seize their pens and mark passages as spurious even in God’s own Holy Writ, putting their pens through whatever they cannot stomach. Can any fairly educated man be afraid of battalions of such enemies? If in the midst of your learned body they had recourse to such trickster’s arts, calling like wizards upon their familiar spirit, you would shout at them, – you would stamp your feet at them. For instance I would ask them what right they have to rend and mutilate the body of the Bible. They would answer that they do not cut out true Scriptures, but prune away supposititious accretions. By authority of what judge? By the Holy Ghost. This is the answer prescribed by Calvin (“Instit.” lib. I, c. 7), for escaping this judgment of the Church whereby spirits of prophesy are examined. Why then do some of you tear out one piece of Scripture, and others another, whereas you all boast of being led by the same Spirit?

The Spirit of the Calvinists receives six Epistles which do not please the Lutheran Spirit, both all the while in full confidence reposing on the Holy Ghost. The Anabaptists call the book of Job a fable, intermixed with tragedy and comedy. How do they know? The Spirit has taught them. Whereas the Song of Solomon is admired by Catholics as a paradise of the soul, a hidden manna, and rich delight in Christ, Castalio, a lewd rogue, has reckoned it nothing better than a love-song about a mistress, and an amorous conversation with Court flunkeys. Whence drew he that intimation? From the Spirit. In the Apocalypse of John, every jot and tittle of which Jerane declares to bear some lofty and magnificent meaning, Luther and Brent and Kemnitz, critics hard to please, find something wanting, and are inclined to throw over the whole book. Whom have they consulted? The Spirit. Luther with preposterous heat pits the Four Gospels one against another (“Praef. in Nov. Test.”), and far prefers Paul’s Epistles to the first three, while he declares the Gospel of St. John above the rest to be beautiful, true, and worthy of mention in the first place, – thereby enrolling even the Apostles, so far as in him lay, as having a hand in his quarrels. Who taught him to do that? The Spirit. Nay this imp of a friar has not hesitated in petulant style to assail Luke’s Gospel because therein good and virtuous works are frequently commended to us. Whom did he consult? The Spirit. Theodore Beza has dared to carp at, as a corruption and perversion of the original, that mystical word from the twenty-second chapter of Luke, “this is the chalice, the new testament in my blood, which (chalice) shall be shed for you” [Greek: potaerion ekchunomenon], because this language admits of no explanation other than that of the wine in the chalice being converted into the true blood of Christ. Who pointed that out? The Spirit. In short, in believing all things every man in the faith of his own spirit, they horribly belie and blaspheme the name of the Holy Ghost. So acting, do they not give themselves away? are they not easily refuted? In an assembly of learned men, such as yours, Gentlemen of the University, are they not caught and throttled without trouble? Should I be afraid on behalf of the Catholic faith to dispute with these men, who have handled with the utmost ill faith not human but heavenly utterances?

I say nothing here of their perverse versions of Scripture, though I could accuse them in this respect of intolerable doings. I will not take the bread out of the mouth of that great linguist, my fellow-Collegian, Gregory Martin, who will do this work with more learning and abundance of detail than I could; nor from others whom I understand already to have that task in hand. More wicked and more abominable is the crime that I am now prosecuting, that there have been found upstart Doctors who have made a drunken onslaught on the handwriting that is of heaven; who have given judgment against it as being in many places defiled, defective, false, surreptitious; who have corrected some passages, tampered with others; torn out others; who have converted every bulwark wherewith it was guarded into Lutheran “spirits,” what I may call phantom ramparts and parted walls. All this they have done that they might not be utterly dumbfounded by falling upon Scripture texts contrary to their errors, texts which they would have found it as hard to get over as to swallow hot ashes or chew stones.

This then has been my First Reason, a strong and a just one. By revealing the shadowy and broken powers of the adverse faction, it has certainly given new courage to a Christian man, not unversed in these studies, to fight for the Letters Patent of the Eternal King against the remnant of a routed foe.

Another thing to incite me to the encounter, and to disparage in my eyes the poor forces of the enemy, is the habit of mind which they continually display in their exposition of the Scriptures, full of deceit, void of wisdom. As philosophers, you would seize these points at once. Therefore I have desired to have you for my audience.

Suppose, for example, we ask our adversaries on what ground they have concocted that novel and sectarian opinion which banishes Christ from the Mystic Supper. If they name the Gospel, we meet them promptly. On our side are the words, “this is my body, this is my blood.” This language seemed to Luther himself so forcible, that for all his strong desire to turn Zwinglian, thinking by that means to make it most awkward for the Pope, nevertheless he was caught and fast bound by this most open context, and gave in to it (Luther, epistol. ad Argent.), and confessed Christ truly present in the Most Holy Sacrament no less unwillingly than the demons of old, overcome by His miracles, cried aloud that He was Christ, the Son of God. Well then, the written text gives us the advantage: the dispute now turns on the sense of what is written. Let us examine this from the words in the context, “my body which is given for you, my blood which hall be shed for many.” Still the explanation on Calvin’s side is most hard, on ours easy and quite plain. What further? Compare the Scriptures, they say, one with another. By all means. The Gospels agree, Paul concurs. The words, the clauses, the whole sentence reverently repeat living bread, signal miracle, heavenly food, flesh, body, blood. There is nothing enigmatical, nothing befogged with a mist of words.

Still our adversaries hold on and make no end of altercation. What are we to do? I presume, Antiquity should be heard; and what we, two parties suspect of one another, cannot settle, let it be settled by the decision of venerable ancient men of all past ages, as being nearer Christ and further removed from this contention. They cannot stand that, they protest that they are being betrayed, they appeal to the word of God pure and simple, they turn away from the comments of men. Treacherous and fatuous excuse. We urge the word of God, they darken the meaning of it. We appeal to the witness of the Saints as interpreters, they withstand them. In short their position is that there shall be no trial, unless you stand by the judgment of the accused party.

And so they behave in every controversy which we start. On infused grace, on inherent justice, on the visible Church, on the necessity of Baptism, on Sacraments and Sacrifice, on the merits of the good, on hope and fear, on the difference of guilt in sins, on the authority of Peter, on the keys, on vows, on the evangelical counsels, on other such points, we Catholics have cited and discussed Scripture texts not a few, and of much weight, everywhere in books, in meetings, in churches, in the Divinity School: they have eluded them. We have brought to bear upon them the “scholia” of the ancients, Greek and Latin: they have refused them. What then is their refuge? Doctor Martin Luther, or else Philip (Melancthon), or anyhow Zwingle, or beyond doubt Calvin and Besa have faithfully laid down the facts. Can I suppose any of you to be so dull of sense as not to perceive this artifice when he is told of it? Wherefore I must confess how earnestly I long for the University Schools as a place where, with you looking on, I could call those carpet-knights out of their delicious retreats into the heat and dust of action, and break their power, not by any strength of my own, – for I am not comparable, not one per cent., with the rest of our people; – but by force of strong case and most certain truth.

THIRD REASON

THE NATURE OF THE CHURCH

At hearing the name of the Church the enemy has turned pale. Still he has devised some explanation which I wish you to notice, that you may observe the ruinous and poverty-stricken estate of falsehood. He was well aware that in the Scriptures, as well of Prophets as of Apostles, everywhere there is made honourable mention of the Church: that it is called the holy city, the fruitful vine, the high mountain, the straight way, the only dove, the kingdom of heaven, the spouse and body of Christ, the ground of truth, the multitude to whom the Spirit has been promised and into whom He breathes all truths that make for salvation; her on whom, taken as a whole, the devil’s jaws are never to inflict a deadly bite; her against whom whoever rebels, however much he preach Christ with his mouth, has no more hold on Christ than the publican or the heathen.

Such a loud pronouncement he dared not gainsay; he would not seem rebellious against a Church of which the Scriptures make such frequent mention: so he cunningly kept the name, while by his definition he utterly abolished the thing, He has depicted the Church with such properties as altogether hide her away, and leave her open to the secret gaze of a very few men, as though she were removed from the senses, like a Platonic Idea. They only could discern her, who by a singular inspiration had got the faculty of grasping with their intelligence this aerial body, and with keen eye regarding the members of such a company. What has become of candour and straightforwardness? What Scripture texts or Scripture meanings or authorities of Fathers thus portray the Church? There are letters of Christ to the Asiatic Churches (Apoc. i. 3), letters of Peter, Paul, John, and others to various Churches; frequent mention in the Acts of the Apostles of the origin and spread of Churches. What of these Churches? Were they visible to God alone and holy men, or to Christians of every rank and degree?

But, doubtless, necessity is a hard weapon. Pardon these subterfuges. Throughout the whole course of fifteen centuries these men find neither town, village nor household professing their doctrine, until an unhappy monk by an incestuous marriage had deflowered a virgin vowed to God, or a Swiss gladiator had conspired against his country, or a branded runaway had occupied Geneva. These people, if they want to have a Church at all, are compelled to crack up a Church all hidden away; and to claim parents whom they themselves have never known, and no mortal has ever set eyes on. Perhaps they glory in the ancestry of men whom every one knows to have been heretics, such as Aerius, Jovinianus, Vigilantius, Helvidius, Berengarius, the Waldenses, the Lollards, Wycliffe, Huss, of whom they have begged sundry poisonous fragments of dogmas.

Wonder not that I have no fear of their empty talk: once I can meet them in the noon-day, I shall have no trouble in dispelling such vapourings. Our conversation with them would take this line. Tell me, do you subscribe to the Church which flourished in bygone ages? Certainly. Let us traverse, then, different countries and periods. What Church? The assembly of the faithful. What faithful? Their names are unknown, but it is certain that there have been many of them. Certain? to whom is it certain? To God Who says so! We, who have been taught of God – stuff and nonsense, how am I to believe it? If you had the fire of faith in you, you would know it as well as you know you are alive. Let in as spectators, could you withhold your laughter?

To think that all Christians should be bidden to join the Church; to beware of being cut down by the spiritual sword; to keep peace in the house of God; to trust their soul to the Church as to the pillar of truth; to lay all their complaints before the Church; to hold for heathen all who are cast out of the Church; and that nevertheless so many men for so many centuries should not know where the Church is or who belong to it! This much only they prate in the darkness, that wherever the Church is, only Saints and persons destined for heaven are contained in it.

Hence it follows that whoever wishes to withdraw himself from the authority of his ecclesiastical superior has only to persuade himself that the priest has fallen into sin and is quite cut off from the Church. Knowing as I did that the adversaries were inventing these fictions, contrary to the customary sense of the Churches in all ages, and that, having lost the whole substance, they still wished in their difficulties to retain the name, I took comfort in the thought of your sagacity, and so promised myself that, as soon as ever you had cognisance of such artifices by their own confession, you would at once like men of mark and intelligence rend asunder the web of foolish sophistry woven for your undoing.

FOURTH REASON

COUNCILS

In the infant Church a grave question about lawful ceremonies, which troubled the minds of believers, was solved by the gathering of a Council of Apostles and elders. The Children believed their parents, the sheep their shepherds, commanding in their words, “It hath seemed good to the Holy Ghost and to us” (Acts xv). There followed for the extirpation of various heresies in various several ages, four Oecumenical Councils of the ancients, the doctrine whereof was so well established that a thousand years ago (see St. Gregory the Great’s Epistles, lib. i. cap. 24) singular honour was paid to it as to an utterance of God. I will travel no further abroad. Even in our home, in Parliament (ann. 1 Elisabeth), the same Councils keep their former right and their dignity inviolate. These I will cite, and I will call thee, England, my sweet country, to witness. If, as thou professest, thou wilt reverence these four Councils, thou shalt give chief honour to the Bishop of the first See, that is to Peter: thou shalt recognise on the altar the unbloody sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Christ: thou shalt beseech the blessed martyrs and all the saints to intercede with Christ on thy behalf: thou shalt restrain womanish apostates from unnatural vice and public incest: thou shalt do many things that thou art undoing, and wish undone much that thou art doing. Furthermore, I promise and undertake to show, when opportunity offers, that the Synods of other ages, and notably the Synod of Trent, have been of the same authority and credence as the first.

Armed therefore with the strong and choice support of all the Councils, why should I not enter into this arena with calmness and presence of mind, watchful to keep an eye on my adversary and see on what point he will show himself? I will produce testimonies most evident that he cannot wrest aside. Possibly he will take to scolding, and endeavour to talk against time, but he will not elude the eyes and ears of men who will watch him hard, as you will do, if you are the men I take you for.

But if there shall be any one found so stark mad as to set his single self up as a match for the senators of the world, men whose greatness, holiness, learning and antiquity is beyond all exception, I shall be glad to look upon that face of impudence; and when I have shown it to you, I will leave the rest to your own thoughts. Meanwhile I will say thus much: The man who refuses consideration and weight to a Plenary Council, brought to a conclusion in due and orderly fashion, seems to me witless, brainless, a dullard in theology, and a fool in politics. If ever the Spirit of God has shone upon the Church, then surely is the time for the sending of divine aid, when the most manifest religiousness, ripeness of judgment, science, wisdom, dignity of all the Churches on earth have flocked together in one city, and with employment of all means, divine and human, for the investigation of truth, implore the promised Spirit that they may make wholesome and prudent decrees.

Let there now leap to the front some mannikin master of an heretical faction, let him arch his eyebrows, turn up his nose, rub his forehead, and scurrilously take upon himself to judge his judges, what sport, what ridicule will he excite! There was found a Luther to say that he preferred to Councils the opinions of two godly and learned men (say his own and Philip Melanchthon’s) when they agreed in the name of Christ. Oh what quackery! There was found a Kemnitz to try the Council of Trent by the standard of his own rude and giddy humour. What gained he thereby? Infamy. While he, unless he takes care, shall be buried with Arius, the Synod of Trent, the older it grows, shall flourish the more, day by day, and year by year. Good God! what variety of nations, what a choice assembly of Bishops of the whole world, what a splendid representation of Kings and Commonwealths, what a quintessence of theologians, what sanctity, what tears, what fears, what flowers of Universities, what tongues, what subtlety, what labour, what infinite reading, what wealth of virtues and of studies filled that august sanctuary! I have myself heard Bishops, eminent and prudent men, – and among them Antony, Archbishop of Prague, by whom I was made Priest, – exulting that they had attended such a school for some years; so that, much as they owed to Kaiser Ferdinand, they considered that he had shown them no more royal and abundant bounty than this of sending them to sit in that Academy of Trent as Legates from Bohemia. The Kaiser understood this, and on their return he welcomed them with the words, “We have kept you at a good school.”

Invited as our adversaries have been under a safe conduct, why have they not hastened thither, publicly to refute those against whom they go on quacking like frogs from their holes? “They broke their promise to Huss and Jerome,” is their reply. Who broke it? “The Fathers of the Council of Constance.” It is false; they never gave any promise. But anyhow, not even Huss would have been punished had not the perfidious and pestilent fellow been brought back from that flight which the Emperor Sigusmund had forbidden him under pain of death; had he not violated the conditions which he had agreed to in writing with the Kaiser and thereby nullified all the value of that safe-conduct. Huss’s hasty wickedness played him false. For, having instigated deeds of savage violence in his native Bohemia, and being bidden thereupon to present himself at Constance, he despised the prerogative of the Council, and sought his safe-conduct of the Kaiser. Caesar signed it; the Christian world, greater than Caesar, cancelled the signature. The heresiarch refused to return to a sound mind, and so perished. As for Jerome of Prague, he came to Constance protected by no one; he was detected and arraigned; he spoke in his own behalf, was treated very kindly, went free whither he would; he was healed, abjured his heresy, relapsed, and was burnt.

Why do they so often drag out one case in a thousand? Let them read their own annals. Martin Luther himself, that abomination of God and men, was put in court at Augsburg before Cardinal Cajetan: there did he not belch out all he could, and then depart in safety, fortified with a letter of Maximilian? Likewise, when he was summoned to Worms, and had against him the Kaiser and most of the Princes of the Empire, was he not safe under the protection of the Kaiser’s word? Lastly, at the Diet of Augsburg, in presence of Charles V., an enemy of heretics, flushed with victory, master of the situation, did not the heads of the Lutherans and Zwinglians, under truce, present their Confessions, so frequently re-edited, and depart in peace? Not otherwise had the letter from Trent provided most ample safe-guards for the adversary; he would not take advantage of them. The fact is, he airs his condition in corners, where he expects to figure as a sage by coming out with three words of Greek: he shrinks from the light, which should place him in the number of men of letters [“lilleratorum” {transcribers note: the Latin is interpolated into the translation here}] and call him to sit in honourable place. Let them obtain for English Catholics such a written promise of impunity, if they love the salvation of souls. We will not raise the instance of Huss: relying on the Sovereign’s word, we will fly to Court.

But, to return to the point whence I digressed, the General Councils are mine, the first, the last, and those between. With them I will fight. Let the adversary look for a javelin hurled with force, which he will never be able to pluck out. Let Satan be overthrown in him, and Christ live.

FIFTH REASON

FATHERS

At Antioch, in which city the noble surname of Christians first became common, there flourished “Doctors,” that is, eminent theologians, and “Prophets,” that is, very celebrated preachers (Acts xiii. 1). Of this sort were the scribes and wise men, learned in the kingdom of God, bringing forth new things and old (Matth. xiii. 52; xxiii. 34), knowing Christ and Moses, whom the Lord promised to His future flock. What a wicked thing it is to scout these teachers, given as they are by way of a mighty boon! The adversary has scouted them. Why? Because their standing means his fall. Having found that out for certain beyond doubt, I have asked for a fight unqualified, not that sham-fight in which the crowds in the street engage, and skirmish with one another, but the earnest and keen struggle in which we join in the arena of yon philosophers: foot to foot, and man close gripping man.

If ever we shall be allowed to turn to the Fathers, the battle is lost and won: they are as thoroughly ours as is Gregory XIII. himself, the loving Father of the children of the Church. To say nothing of isolated passages, which are gathered from the records of the ancients, apt and clear statements in defence of our faith, we hold entire volumes of these Fathers, which professedly illustrate in clear and abundant light the Gospel religion which we defend. Take the twofold “Hierarchy” of the martyr Dionysius, what classes, what sacrifices, what rites does he teach? This fact struck Luther so forcibly that he pronounced the works of this Father to be “such stuff as dreams are made of, and that of the most pernicious kind.” In imitation of his parent, an obscure Frenchman, Caussee, has not hesitated to call this Dionysius, the Apostle of an illustrious nation, “an old dotard.” Ignatius has given grievous offence to the Centuriators of Magdeburg, as also to Calvin, so that these men, the offscouring of mankind, have noted in his works “unsightly blemishes and tasteless prosings.” In their judgment, Irenaeus has brought out “a fanatical production”: Clement, the author of the “Stromata,” has produced “Tares and dregs”: the other Fathers of this age, Apostolic men to be sure, “have left blasphemies and monstrosities to posterity.” In Tertullian they eagerly seize upon what they have learned from us, in common with us, to detest; but they should remember that his book “On Prescriptions,” which has so signally smitten the heretics of our times, was never found fault with. How finely, how, clearly, has Hippolytus, Bishop of Porto pointed out beforehand the power of Antichrist, the times of Luther! They call him, therefore, “a most babyish writer, an owl.” Cyprian, the delight and glory of Africa, that French critic Caussee, and the Centuriators of Magdeburg, have termed “stupid, God-forsaken corrupter of repentance.” What harm has he done? He has written “On Virgins, On the Lapsed, On the Unity of the Church,” such treatises as also such letters to Cornelius, the Roman Pontiff, that, unless credence be withdrawn from this Martyr, Peter Martyr Vermilius and all his associates must count for worse than adulterers and men guilty of sacrilege. And, not to dwell longer on individuals, the Fathers of this age are all condemned “for wonderful corruption of the doctrine of repentance.” How so? Because the austerity of the Canons in vogue at that time is particularly obnoxious to this plausible sect which, better fitted for dining-rooms than for churches, is wont to tickle voluptuous ears and to sew “cushions on every arm” (Ezech. xiii. 18). Take the next age, what offence has that committed?

Chrysostom and those Fathers, forsooth, have “foully obscured the justice of faith.” Gregory Nazianzen whom the ancients called eminently “the Theologian,” is in the judgment of Caussee “a chatter-box, who did not know what he was saying.” Ambrose was “under the spell of an evil demon.” Jerome is “as damnable as the devil, injurious to the Apostle, a blasphemer, a wicked wretch.” To Gregory Massow, “Calvin alone is worth more than a hundred Augustines.” A hundred is a small number: Luther “reckons nothing of having against him a thousand Augustines, a thousand Cyprians, a thousand Churches.” I think I need not carry the matter further. For when men rage against the above-mentioned Fathers, who can wonder at the impertinence of their language against Optatus, Hilary, the two Cyrils, Epiphanius, Basil, Vincent, Fulgentius, Leo, and the Roman Gregory.

However, if we grant any just defence of an unjust cause, I do not deny that the Fathers wherever you light upon them, afford the party of our opponents matter they needs must disagree with, so long as they are consistent with themselves. Men who have appointed fast-days, how must they be minded in regard of Basil, Gregory, Nazianzen, Leo, Chrysostom, who have published telling sermons on Lent and prescribed days of fasting as things already in customary use? Men who have sold their souls for gold, lust, drunkenness and ambitious display, can they be other than most hostile to Basil, Chrysostom, Jerome, Augustine, whose excellent books are in the hands of all, treating of the institute, rule, and virtues of monks?

Men who have carried the human will into captivity, who have abolished Christian funerals, who have burnt the relics of Saints, can they possibly be reconciled to Augustine, who has composed three books on Free Will, one on Care for the Dead, besides sundry sermons and a long chapter in a noble work on the Miracles wrought at the Basilicas and Monuments of the Martyrs? Men who measure faith by their own quips and quirks, must they not be angry with Augustine, of whom there is extant a remarkable Letter against a Manichean, in which he professes himself to assent to Antiquity, to Consent, to Perpetuity of Succession, and to the Church which, alone among so many heresies, claims by prescriptive right the name of Catholic?

Optatus, Bishop of Milevis, refutes the Donatist faction by appeal to Catholic communion: he accuses their wickedness by appeal to the decree of Melchiades: he convicts their heresy by reference to the order of succession of Roman Pontiffs: he lays open their frenzy in their defilement of the Eucharist and of schism: he abhors their sacrilege in their breaking of altars “on which the members of Christ are borne,” and their pollution of chalices “which have held the blood of Christ.” I greatly desire to know what they think of Optatus, whom Augustine mentions as a venerable Catholic Bishop, the equal of Ambrose and of Cyprian; and Fulgentius as a holy and faithful interpreter of Paul, like unto Augustine and Ambrose.

They sing in their churches the Creed of Athanasius. Do they stand by him? That grave anchor who has written an elaborate book in praise of the Egyptian hermit Antony, and who with the Synod of Alexandria suppliantly appealed to the judgment of the Apostolic See, the See of St. Peter. How often does Prudentius in his Hymns pray to the martyrs whose praises he sings! how often at their ashes and bones does he venerate the King of Martyrs! Will they approve his proceeding? Jerome writes against Vigilantius in defence of the relics of the Saints and the honours paid to them; as also against Jovinian for the rank to be allowed to virginity. Will they endure him? Ambrose honoured his patron saints Gervase and Protase with a most glorious solemnity by way of putting the Arians to shame. This action of his was praised by most godly Fathers, and God honoured it with more than one miracle. Are they going to take a kindly view off Ambrose here? Gregory the Great, our Apostle, is most manifestly with us, and therefore is a hateful personage to our adversaries. Calvin, in his rage, says that he was not brought up in the school of the Holy Ghost, seeing that he had called holy images the books of the illiterate.

Time would fail me were I to try to count up the Epistles, Sermons, Homilies, Orations, Opuscula and dissertations of the Fathers, in which they have laboriously, earnestly and with much learning supported the doctrines of us Catholics. As long as these works are for sale at the booksellers’ shops, it will be vain to prohibit the writings of our controversialists; vain to keep watch at the ports and on the sea-coast; vain to search houses, boxes, desks, and book-chests; vain to set up so many threatening notices at the gates. No Harding, nor Sanders, nor Allen, nor Stapleton, nor Bristow, attack these new-fangled fancies with more vigour than do the Fathers whom I have enumerated. As I think over these and the like facts, my courage has grown and my ardour for battle, in which whatever way the adversary stirs, unless he will yield glory to God, he will be in straits. Let him admit the Fathers, he is caught: let him shut them out, he is undone.

When we were young men, the following incident occurred. John Jewell, a foremost champion of the Calvinists of England, with incredible arrogance challenged the Catholics at St. Paul’s, London, invoking hypocritically and calling upon the Fathers, who had flourished within the first six hundred years of Christianity. His wager was taken up by the illustrious men who were then in exile at Louvain, hemmed in though they were with very great difficulties by reason of the iniquity of their times. I venture to assert that that device of Jewell’s, stupid, unconscionable, shameless as it was, qualities which those writers happily brought out, did so much good to our countrymen that scarcely anything in my recollection has turned out to the better advantage of the suffering English Church. At once an edict is hung up on the doors, forbidding the reading or retaining of any of those books, whereas they had come out, or were wrung out, I may almost say, by the outcry that Jewell had raised. The result was that all the persons interested in the matter came to understand that the Fathers were Catholics, that is to say, ours. Nor has Lawrence Humphrey passed over in silence this wound inflicted on him and his party. After high praise of Jewell in other respects, he fixes on him this role of inconsiderateness, that he admitted the reasonings of the Fathers, with whom Humphrey declares, without any beating about the bush, that he has nothing in common nor ever will have.

We also sounded once in familiar discourse Toby Matthews, now a leading preacher, whom we loved for his good accomplishments and the seeds of virtue in him; we asked him to answer honestly whether one who read the Fathers assiduously could belong to that party which he supported. He answered that he could not, if, besides reading, he also believed them.[1] This saying is most true; nor do I think that either he at the present time, or Matthew Hutten, a man of name, who is said to read the Fathers with an assiduity that few equal, or other adversaries who do the like, are otherwise minded.

Thus far I have been able to descend with security into this field of conflict, to wage war with men, who, as though they held a wolf by the ears, are compelled to brand their cause with an everlasting stigma of shame, whether they refuse the Fathers or whether they call for them. In the one case they are preparing to run away, in the other they are caught by the throat.

SIXTH REASON

THE GROUNDS OF ARGUMENT ASSUMED BY THE FATHERS

If ever any men took to heart and made their special care, – as men of our religion have made it and should make it their special care, – to observe the rule, “Search the Scriptures” (John v. 39), the holy Fathers easily come out first and take the palm for the matter of this observance. By their labour and at their expense Bibles have been transcribed and carried among so many nations and tongues by the perils they have run and the tortures they have endured the Sacred Volumes have been snatched from the flames and devastation spread by enemies: by their labours and vigils they have been explained in every detail. Night and day they drank in Holy Writ, from all pulpits they gave forth Holy Writ, with Holy Writ they enriched immense volumes, with most faithful commentaries they unfolded the sense of Holy Writ, with Holy Writ they seasoned alike their abstinence and their meals, finally, occupied about Holy Writ they arrived at decrepit old age.

And if they also frequently have argued from the Authority of Elders, from the Practice of the Church, from the Succession of Pontiffs, from ecumenical Councils, from Apostolic Traditions, from the Blood of Martyrs, from the decrees of Bishops, from Miracles, yet most persistently of all and most willingly do they set forth in close array the testimonies of Holy Writ: these they press home, on these they dwell, to this “armour of the strong” (Cant. iii. 7), for the best of reasons, is the first and the most honourable part assigned by these valiant leaders in their work of forgiving and keeping in repair the City of God against the assaults of the wicked.

Wherefore I do all the more wonder at that haughty and famous objection of the adversary, who, like one looking for water in a running stream, takes exception to the lack of Scripture texts in writings crowded with Scripture texts. He says he will agree with the Fathers so long as they keep close to Holy Scripture. Does he mean what he says? I will see then that there come forth, armed and begirt with Christ, with Prophets and Apostles, and with all array of Biblical erudition, those celebrated authors, those ancient Fathers, those holy men, Dionyius, Cyprian, Athanasius, Basil, Nazianzen, Ambrose, Jerome, Chrysostom, Augustine, and the Latin Gregory. Let that faith reign in England, Oh that it may reign! which these Fathers, dear lovers of the Scriptures, build up out of the Scriptures. The texts that they bring, we will bring: the texts they confer, we will confer: what they infer, we will infer. Are you agreed? Out with it and say so, please. Not bit of it, he says, unless they expound rightly. What is this “rightly”? At your discretion. Are you not ashamed of the vicious circle?

Hopeful as I am that in flourishing Universities there will be gathered together a good number, who will be no dull spectators, but acute judges of these controversies and who will weigh for what they are worth the frivolous answers of our adversaries, I will gladly await this meeting-day, as one minded to lead forth against wooded hillocks [cf. Cicero “in Catilinam” ii. 11], covered with unarmed tramps, the nobility and strength of the Church of Christ.

SEVENTH REASON

HISTORY

Ancient History unveils the primitive face of the Church. To this I appeal. Certainly, the more ancient historians, whom our adversaries also habitually, consult, are enumerated pretty well as follows: Eusebius, Damasus, Jerome, Rufinus, Orosius, Socrates, Sozomen, Theodoret Cassiodorus, Gregory of Tours, Usuard, Regino, Marianus, Sigebert, Zonaras, Cedrinus, Nicephorus. What have they to tell? The praises of our religion, its progress, vicissitudes, enemies. Nay, and this is a point I would have you observe diligently, they who in deadly hatred dissent from us, – Melancthon, Pantaleon, Funck, the Centuriators of Magdeburg, – on applying themselves to write either the chronology or the history of the Church, if they did not get together the exploits of our heroes, and heap up the accounts of the frauds and crimes of the enemies of our Church, would pass by fifteen hundred years with no story to tell.

Along with the above-mentioned consider the local historians, who have searched with laborious curiosity into the transactions of some one particular nation. These men, wishing by all means to enrich and adorn the Sparta which they had gotten for their own, and to that effect not passing over in silence even such things as banquets of unusual splendour, or sleeved tunics, or hilts of daggers, or gilt spurs, and other such minutiae having any smack of revelry about them, surely, if they had heard of any change in religion, or any falling off from the standard of early ages, would have related it, many of them; or, if not many, at least several; if not several, some one anyhow. Not one, well-disposed or ill-disposed towards us, has related anything of the sort, or even dropped the slightest hint of the same.

For example. Our adversaries grant us, – they cannot do otherwise, – that the Roman Church was at one time holy, Catholic, Apostolic, at the time when it deserved these eulogiums from St. Paul: “Your faith is spoken of in the whole world. Without ceasing I make a commemoration of you. I know that when I come to you, I shall come in the abundance of the blessing of Christ. All the Churches of Christ salute you. Your obedience is published in every place” (Rom. i. 8, 9; xv. 29; xvi. 17, 19): at the time when Paul, being kept there in free custody, was spreading the gospel (Acts xxviii. 31) : at the time when Peter once in that city was ruling “the Church gathered at Babylon” (1 Peter v. 13): at the time when that Clement, so singularly praised by the Apostle (Phil. iv. 3) was governing the Church: at the time when the pagan Caesars, Nero, Domitian, Trajan, Antoninus, were butchering the Roman Pontiffs: also at the time when, as even Calvin bears witness, Damasus, Siricius, Anastasius and Innocent guided the Apostolic bark. For at this epoch he generously allows that men, at Rome particularly, had so far not swerved from Gospel teaching.

When then did Rome lose this faith so highly celebrated? When did she cease to be what she was before? At what time, under what Pontiff, by what way, by what compulsion, by what increments, did a foreign religion come to pervade city and world? What outcries, what disturbances, what lamentations did it provoke? Were all mankind all over the rest of the world lulled to sleep, while Rome, Rome I say, was forging new Sacraments, a new Sacrifice, new religious dogma? Has there been found no historian, neither Greek nor Latin, neither far nor near, to fling out in his chronicles even an obscure hint of so remarkable a proceeding?

Therefore this much is clear, that the articles of our belief are what History, manifold and various, History the messenger of antiquity, and life of memory, utters and repeats in abundance; while no narrative penned in human times records that the doctrines foisted in by our opponents ever had any footing in the Church. It is clear, I say, that the historians are mine, and that the adversary’s raids upon history are utterly without point. No impression can they make unless the assertion be first received, that all Christians of all ages had lapsed into gross infidelity and gone down to the abyss of hell, until such time as Luther entered into an unblessed union with Catherine Bora.

EIGHTH REASON

PARADOXES

For myself, most excellent Sirs, when, choosing out of many heresies, I think over in my mind certain portentous errors of self-opinionated men, errors that it will be incumbent on me to refute, I should condemn myself of want of spirit and discernment if in this trial of strength I were to be afraid of any man’s ability or powers. Let him be able, let him be eloquent, let him be a practised disputant, let him be a devourer of all books, still his thought must dry up and his utterance fail him when he shall have to maintain such impossible positions as these. For we shall dispute, if perchance they will allow us, on God, on Christ, on Man, on Sin, on Justice, on Sacraments, on Morals. I shall see whether they will dare to speak out what they think, and what under the constraint of their situation they publish in their miserable writings. I will take care that they know these maxims of their teachers:

OF GOD. – “God is the author and cause of evil, willing it, suggesting it, effecting it, commanding it, working it out, and guiding the guilty counsels of the wicked to this end. As the call of Paul, so the adultery of David, and the wickedness of the traitor Judas, was God’s own work” (Calvin, “Institut”. i. 18; ii. 4; iii. 23, 24). This monstrous doctrine, of which Philip Melanchthon was for once ashamed, Luther however, of whom Philip had learned it, extols as an oracle from heaven with wonderful praises, and on that score puts his foster-child all but on an equality, with the Apostle Paul (Luther, “De servo arbitrio”). I will also enquire what was in Luther’s mind, whom the English Calvinists pronounce to be “a man given of God for the enlightenment of the world,” when he wished to take this versicle out of the Church’s prayers, “Holy Trinity, one God, have mercy on us.”

OF CHRIST. – I will proceed to the person of Christ. I will ask what these words, “Christ the Son of God, God of God,” mean to Calvin, who says, “God of Himself” (“Instit.” i. 13); or to Beza, who says, “He is not begotten of the essence of the Father” (Beza in Josue, nn. 23, 24). Again. Let there be set up two hypostate unions in Christ, one of His soul with His flesh, the other of His Divinity with His Humanity (Beza, “Contra Schmidel”). The passage in John x. 30, “I and the Father are one,” does not show Christ to be God, consubstantial with God the Father (Calvin on John x.), the fact is, says Luther, “my soul hates this word, homousion.” Go on. Christ was not perfect in grace from His infancy, but grew in gifts of the soul like other men, and by experience daily became wiser, so that as a little child He laboured under ignorance (Melanchthon on the gospel for first Sunday after Epiphany). Which is as much as to say that He was defiled with the stain and vice of original sin. But observe still more direful utterances. When Christ, praying in the Garden, was streaming with a sweat of water and blood, He shuddered under a sense of eternal damnation, He uttered an irrational cry, an unspiritual cry, a sudden cry prompted by the force of His distress, which He quickly checked as not sufficiently premeditated (Marlorati in Matth. xxvi.; Calvin “in Harm. Evangel.”). Is there anything further? Attend. When Christ Crucified exclaimed, “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me,” He was on fire with the flames of hell, He uttered a cry of despair, He felt exactly as if nothing were before Him but to perish in everlasting death (Calvin “in Harm. Evangel.”).

To this also let them add something, if they can. Christ, they say, descended into hell, that is, when dead, He tasted hell not otherwise than do the damned souls, except that He was destined to be restored to Himself: for since by His mere bodily death He would have profited us nothing, He needed in soul also to struggle with everlasting death, and in this way to pay the debt of our crime and our punishment. And lest any one might haply suspect that this theory had stolen upon Calvin unawares, the same Calvin calls “all of you who have repelled this doctrine, full as it is of comfort, God-forsaken boobies” (Institut. ii. 16). Times, times, what a monster you have reared! That delicate and royal Blood, which ran in a flood from the lacerated and torn Body of the innocent Lamb, one little drop of which Blood, for the dignity of the Victim, might have redeemed a thousand worlds, availed the human race nothing, unless “the mediator of God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (I Tim. ii. 5) had borne also “the second death” (Apoc. xx. 6), the death of the soul, the death to grace, that accompaniment only of sin and damnable blasphemy! In comparison with this insanity, Bucer, impudent fellow that he is, will appear modest, for he (on Matth. xxvi.), by an explanation very preposterous, or rather, an inept and stupid tautology, takes “hell” in the creed to mean the tomb.

Of the Anglican sectaries, some are wont to adhere to their idol, Calvin, others to their great master, Bucer; some also murmur in an undertone against this article, wishing that it may be quietly removed altogether from the Creed, that it may give no more trouble. Nay, this was actually tried in a meeting at London, as I remember being told by one who was present, Richard Cheyne, a miserable old man, who was badly mauled by robbers outside, and, for all that, never entered his father’s house.[2]

OF THE MAN. – And thus far of Christ. What of Man? The image of God is utterly blotted out in man, not the slightest spark of good is left: his whole nature in all the parts of his soul is so thoroughly overturned that, even after he is born again and sanctified in baptism, there is nothing whatever within him but mere corruption and contagion. What does this lead up to? That they who mean to seize glory by faith alone may wallow in the filth of every turpitude, may accuse nature, despair of virtue, and discharge themselves of the commandments (Calvin, “Instit.” ii. 3).

OF SIN. – To this, Illyricus, the standard-bearer of the Magdeburg company, has added his own monstrous teaching about original sin, which he makes out to be the innermost substance of souls, whom, since Adam’s fall, the devil himself engenders and transforms into himself. This also is a received maxim in this scum of evil doctrine, that all sins are equal, yet with this qualification (not to revive the Stoics), “if sins are weighed in the judgment of God.” As if God, the most equitable judge, were to add to our burden rather than lighten it; and, for all His justice, were to exaggerate and make it what it is not in itself. By this estimation, as heavy an offence would be committed against God, judging in all severity, by the innkeeper who has killed a barn-door cock, when he should not have done, as by that infamous assassin who, his head full of Beza, stealthily slew by the shot of a musket the French hero, the Duke of Guise, a Prince of admirable virtue, than which crime our world has seen in our age nothing more deadly, nothing more lamentable.

OF GRACE. – But perchance they who are so severe in the matter of sin philosophise magnificently on divine grace, as able to bring succour and remedy to this evil. Fine indeed is the function which they assign to grace, which their ranting preachers say is neither infused into our hearts, nor strong enough to resist sin, but lies wholly outside of us, and consists in the mere favour of God, – a favour which does not amend the wicked, nor cleanse, nor illuminate, nor enrich them, but, leaving still the old stinking ordure of their sin, dissembles it by God’s connivance, that it be not counted unsightly and hateful. And with this their invention they are so delighted that, with them, even Christ is not otherwise called “full of grace and truth” than inasmuch as God the Father has borne wonderful favour to Him (Bucer on John i: Brent hom. 12 on John).

OF RIGHTEOUSNESS. – What sort of thing then is righteousness? A relation. It is not made up of faith, hope and charity, vesting the soul in their splendour; it is only a hiding away of guilt, such that, whoever has seized upon this righteousness by faith alone, he is as sure of salvation as though he were already enjoying the unending joy of heaven. Well, let this dream pass: but how can one be sure of future perseverance, in the absence of which a man’s exit would be most miserable, though for a time he had observed righteousness purely and piously? Nay, says Calvin (“Instit.” iii. 2), unless this your faith foretells you your perseverance assuredly, without possibility of hallucination, it must be cast aside as vain and feeble. I recognise the disciple of Luther. A Christian, said Luther (“De captivitate Babylonis”), cannot lose his salvation, even if he wanted, except by refusing to believe.

OF THE SACRAMENTS. – I hasten to pass on to the Sacraments. None, none, not two, not one, O holy Christ, have they left. Their bread is poison; and as for their baptism, though it is still true baptism, nevertheless in their judgment it is nothing, it is not a wave of salvation, it is not a channel of grace, it does not apply to us the merits of Christ, it is a mere token of salvation (Calvin, “Instit.” iv. 15). Thus they have made no more of the baptism of Christ, so far as the nature of the thing goes, than of the ceremony of John. If you have it, it is well; if you go without it, there is no loss suffered; believe, you are saved, before you are washed. What then of infants, who, unless they are aided by the virtue of the Sacrament, poor little things, gain nothing by any faith of their own? Rather than allow anything to the Sacrament of baptism, say the Magdeburg Centuriators (Cent. v. 4.), let us grant that there is faith in the infants themselves, enough to save them; and that the said babies are aware of certain secret stirrings of this faith, albeit they are not yet aware whether they are alive or not. A hard nut to crack! If this is so very hard, listen to Luther’s remedy. It is better, he says (“Advers. Cochl.”), to omit the baptism; since, unless the infant believes, to no purpose is it washed. This is what they say, doubtful in mind what absolutely to affirm. Therefore let Balthasar Pacimontanus step in to sort the votes. This father of the Anabaptists, unable to assign to infants any stirring of faith, approved Luther’s suggestion; and, casting infant baptism out of the churches, resolved to wash at the sacred font none who was not grown up. For the rest of the Sacraments, though that many headed beast utters many insults, yet, seeing that they are now of daily occurrence, and our ears have grown callous to them, I here pass them over.

OF MORALITY. – There remain the sayings of the heretics concerning life and morals, the noxious goblets which Luther has vomited on his pages, that out of the filthy hovel of his one breast he might breathe pestilence upon his readers. Listen patiently, and blush, and pardon me the recital. If the wife will not, or cannot, let the handmaid come (“Serm. de matrimon.”); seeing that commerce with a wife is as necessary to every man as food, drink, and sleep. Matrimony is much more excellent than virginity. Christ and Paul dissuaded men from virginity (“Liber de vot. evangel.”). But perhaps these doctrines are peculiar to Luther. They are not. They have been lately defended by my friend Chark but miserably and timidly. Do you wish to hear any more? Certainly. The more wicked you, are, he says, the nearer you are to grace (“Serm. de. pisc. Petri”). All good actions are sins, in God’s judgment, mortal sins; in God’s mercy, venial. No one thinks evil of his own will. The Ten Commandments are nothing to Christians. God cares nought at all about our works. They alone rightly partake of the Lord’s Supper, who bury consciences sad, afflicted, troubled, confused, erring. Sins are to be confessed, but to anyone you like; and if he absolves you even in joke, provided you believe, you are absolved. To read the Hours of the Divine Office is not the function of priests, but of laymen. Christians are free from the enactments of men (Luther, “De servo arbitrio, De captivilate Babylon”).

I think I have stirred up this puddle sufficiently. I now finish. Nor must you think me unfair for having turned my argument against Lutherans and Zwinglians indiscriminately. For, remembering their common parentage, they wish to be brothers and friends to one another; and they take it as a grave affront, whenever any distinction is drawn between them in any point but one. I am not of consequence enough to claim for myself so much as an undistinguished place among the select theologians who at this day have declared war on heresies: but this I know, that, puny as I am, I run no risk while, supported by the grace of Christ, I shall do battle, with the aid of heaven and earth, against such fabrications as these, so odious, so tasteless, so stupid.

NINTH REASON

SOPHISM

It is a shrewd saying that a one-eyed man may be king among the blind. With uneducated people a mock-proof has force which a school of philosophers dismisses with scorn. Many are the offences of the adversary under this head; but his case is made out by four fallacies chiefly, fallacies which I would rather unravel in the University than in a popular audience.

The first vice is [Greek: skiamachia], with mighty effort hammering at breezes and shadows. In this way: against such as have sworn to celibacy and vowed chastity, because, while marriage is good, virginity is better (1 Cor. vii.), Scripture texts are brought up speaking honourably of marriage. Whom do they hit? Against the merit of a Christian man, a merit dyed in the Blood of Christ, otherwise null, testimonies are alleged whereby we are bidden to put our trust neither in nature nor in the law, but in the Blood of Christ. Whom do they refute? Against those who worship Saints, as Christ’s servants, especially acceptable to Him, whole pages are quoted, forbidding the worship of many gods? Where are these many gods? By such arguments, which I find in endless quantity in the writings of heretics, they cannot hurt us, they may bore you.

Another vice is [Greek: logomachia], which leaves the sense, and wrangles loquaciously over the word. “Find me Mass or Purgatory in the Scriptures,” they say. What then? Trinity, Consubstantial, Person, are they nowhere in the Bible, because these words are not found? Allied to this fault is the catching at letters, when, to the neglect of usage and the mind of the speakers, war is waged on the letters of the alphabet. For instance, thus they say: “Presbyter to the Greeks means nothing else than elder; Sacrament, any mystery”. On this, as on all other points, St. Thomas shrewdly observes: “In words, we must look not whence they are derived, but to what meaning they are put.”

The third vice is [Greek: homonumia], which has a very wide range. For example: “What is the meaning of an Order of Priests, when John has called us all priests?” (Apoc. v. 10). He has also added this: “we shall reign upon the earth”. What then is the use of Kings? Again: “the Prophet” (Isaias lviii.) “cries up a spiritual fast, that is, abstinence from inveterate crimes. Farewell then to any discernment of meats and prescription of days.” Indeed? Mad therefore were Moses, David, Elias, the Baptist, the Apostles, who terminated their fasts in two days, three days, or in so many weeks, which fasting, being from sin, ought to have been perpetual. You have already seen what manner of argument this is. I hasten on.

Added to the above is a fourth vice, “Vicious Circle,” in this way. Give me the notes, I say, of the Church. “The word of God and undefiled Sacraments”. Are these with you? “Who can doubt it?” I do, I deny it utterly. “Consult the word of God.” I have consulted it, and I favour you less than before. “Ah, but it is plain.” Prove it to me. “Because we do not depart a nail’s breadth from the word of God.” Where is your persecution? Will you always go on taking for an argument the very point that is called in question? How often have I insisted on this already? Do wake up: do you want torches applied to you? I say that your exposition of the word of God is perverse and mistaken: I have fifteen centuries to bear me witness stand by an opinion, not mine, nor yours, but that of all these ages. “I will stand by the sentence of the word of God: the Spirit breatheth where it will” (John iii. 8). There he is at it again; what circumvolutions, what wheels he is making! This trifler, this arch-contriver of words and sophisms, I know not to whom he can be formidable: tiresome he possibly will be. His tiresomeness will find its corrective in your sagacity: all that was formidable about him facts have taken away.

TENTH REASON

ALL MANNER OF WITNESS

“This shall be to you a straight way, so that fools shall not go astray in it” (Isaias xxxv. 8).

Who is there, however small and lost in the crowd of illiterates, that, with a desire of salvation and some little attention, cannot see, cannot keep to the path of the Church, so admirably smoothed out, eschewing brambles and rocks and pathless wastes! For, as Isaias prophesies, this path shall be plain even to the uneducated; most plain therefore, if you choose, to you.

COELITES. – Let us put before our eyes the theatre of the universe: let us wander everywhere: all things supply us with an argument. Let us go to heaven: let us contemplate roses and lilies, Saints empurpled with martyrdom or white with innocence: Roman Pontiffs, I say, three and thirty in a continuous line put to death: Pastors all the world over, who have pledged their blood for the name of Christ: Flocks of faithful, who have followed in the footsteps of their Pastors: all the Saints of heaven, who as shining lights in purity and holiness have gone before the crowd of mankind. You will find that these were ours when they lived on earth, ours when they passed away from this world. To cull a few instances, ours was that Ignatius, who in church matters put no one not even the Emperor, on a level with the Bishop; who committed to writing, that they might not be lost, certain Apostolic traditions of which he himself had been witness. Ours was that anchoret Telesphorus, who ordered the more strict observance of the fast of Lent established by the Apostles. Ours was Irenaeus, who declared the Apostolic faith by the Roman succession and chair (lib. iii. cap. 3). Ours was Pope Victor, who by an edict brought to order the whole of Asia; and though this proceeding seemed to some minds, and even to that holy man Irenaeus, somewhat harsh, yet no one made light of it as coming from a foreign power. Ours was Polycarp, who went to Rome on the question of Easter, whose burnt relics Smyrna gathered, and honoured her Bishop with an anniversary feast and appointed ceremony. Ours were Cornelius and Cyprian, a golden pair of Martyrs, both great Bishops, but greater he, the Roman, who had rescinded the African error; while the latter was ennobled by the obedience which he paid to the elder, his very dear friend. Ours was Sixtus, to whom, as he offered solemn sacrifice at the altar, seven men of the clergy ministered. Ours was his Archdeacon Lawrence, whom the adversaries cast out of their calendar, to whom, twelve hundred years ago, the Consular man Prudentius thus prayed:

What is the power entrusted thee,

And how great function is given thee,

The joyful thanks of Roman citizens prove,

To whom thou grantest their petitions.

Among them, O glory of Christ,

Hear also a rustic poet,

Confessing the crimes of his heart

And publishing his doings.

Hear bountifully the supplication

Of Christ’s culprit Prudentius.

Ours are those highly-blest maids, Cecily, Agatha, Anastasia, Barbara, Agnes, Lucy, Dorothy, Catherine, who held fast against the violent assault of men and devils the virginity they had resolved upon. Ours was Helen, celebrated for the finding of the Lord’s Cross. Ours was Monica, who in death most piously begged prayers and sacrifices to be offered for her at the altar of Christ. Ours was Paula, who, leaving her City palace and her rich estates, hastened on a long journey a pilgrim to the cave at Bethlehem, to hide herself by the cradle of the Infant Christ. Ours were Paul, Hilarion, Antony, those dear ancient solitaries. Ours was Satyrus, own brother to Ambrose, who, when shipwrecked, jumped into the ocean, carrying about his neck in a napkin the Sacred Host, and full of faith swam to shore (Ambrose, “Orat. fun. de Satyro”).

Ours are the Bishops Martin and Nicholas, exercised in watchings, clad in the military garb of hair cloths, fed with fasts. Ours is Benedict, father of so many monks. I should not run through their thousands in ten years. But neither do I set down those whom I mentioned before among the Doctors of the Church. I am mindful of the brevity imposed upon me. Whoever wills, may seek these further details, not only from the copious histories of the ancients, but even much more from the grave authors who have bequeathed to memory almost one man one Saint. Let the reader report to me his judgment concerning those ancient blessed Christians, to what doctrine they adhered, the Catholic or the Lutheran. I call to witness the throne of God, and that Tribunal at which I shall stand to render reason for these Reasons, of everything I have said and done, that either there is no heaven at all, or heaven belongs to our people. The former position we abhor, we fix therefore upon the latter.

DAMNATI. – Now contrariwise, if you please, let us look into hell. There are burnt with everlasting fire, who? The Jews. On what Church have they turned their backs? On ours. Who again? The heathen. What Church have they most cruelly persecuted? Ours. Who again? The Turks. What temples have they destroyed? Ours. Who once more? Heretics. Against what Church are they in rebellion? Against ours. What Church but ours has opposed itself against all the gates of hell?

IUDAEI. – When, after the driving away of the Hebrews, Christian inhabitants began to multiply at Jerusalem, what a concourse of men there was to the Holy Places, what veneration attached to the City, to the Sepulchre, to the Manger, to the Cross, to all the memorials in which the Church delights as a wife in what has been worn by her husband. Hence arose against us the hatred of the Jews, cruel and implacable. Even now they complain that our ancestors were the ruin of their ancestors. From Simon Magus and the Lutherans they have received no wound.

ETHNICI. – Among the heathen, they were the most violent who, throughout the Roman Empire, for three hundred years, at intervals of time, contrived most painful punishments for Christians. What Christians? The fathers and children of our faith. Learn the language of the tyrant who roasted St. Lawrence on the gridiron:

That this is of your rites

The custom and practice, it has been handed down to memory:

This the discipline of the institution,

That priests pour libations from golden cups.

In silver goblets they say

That the sacred blood smokes;

And that in golden candlestick, at the nightly sacrifices,

There stand fixed waxen candles.

Then is it the chief care of the brethren,

As many-tongued report does testify,

To offer from the sale of estates,

Thousands of pence.

Ancestral property made over

To dishonest auctions,

The disinherited successor groans,

Needy child of holy parents.

These treasures are concealed in secret,

In corners of the churches;

And it is believed the height of piety

To strip your sweet children.

Bring out your treasures,

Which by evil arts of persuasion

You have heaped up and hold,

Which you shut up in darkling cave.

Public utility demands this,

The privy purse demands it, the treasury demands it,

That the soldiers may be paid for their services,

And the commander may benefit thereby.

This is your dogma, then:

Give every man his own.

Now Caesar recognises his own

Image, stamped on the coin.

What you know to be Caesar’s, to Caesar

Give; surely what I ask is just.

If I am not mistaken, your Deity

Coins no money,

Nor when he came did he bring

Golden Jacobuses[3] with him;

But he gave his precepts in words,

Empty in point of pocket.

Fulfil the promise of the words

Which you sell the round world over.

Give up your hard cash willingly,

Be rich in words.

(Prudentius, “Hymn on St. Lawrence”).

Whom does this speaker resemble. Against whom does he rage? What Church is it whose sacred vessels, lamps, and ornaments he is pillaging, whose ritual he overthrows? Whose golden patens and silver chalices, sumptuous votive offerings and rich treasure, does he envy? Why, the man is a Lutheran all over. With what other cloak did our Nimrods[4] cover their brigandage, when they embezzled the money of their Churches and wasted the patrimony of Christ? Take on the contrary Constantine the Great, that scourge of the persecutors of Christ, to what Church did he restore tranquillity? To that Church over which Pope Silvester presided, whom he summoned from his hiding-place on Mount Soracte that by his ministry he might receive our baptism. Under what auspices was he victorious? Under the sign of the cross. Of what mother was he the glorious son? Of Helen. To what Fathers did he attach himself? To the Fathers of Nice. What manner of men were they? Such men as Silvester, Mark, Julius, Athanasius, Nicholas. What seat did he ask for in the Synod? The last. Oh how much more kingly was he on that seat than the Kings who have ambitioned a title not due to them! It would be tedious to go into further details. But from these two [Emperors, Decius and Constantine], the one our deadly enemy, the other our warm friend, it may be left to the reader’s conjecture to fix on points of closest resemblance to the one and to the other in the history of our own times. For as it was our cause that went through its agony under Decius, so our cause it was that came out triumphant under Constantine.[5]

TURCAE. – Let us look at the doings of the Turks. Mahomet and the apostate monk Sergius lie in the deep abyss, howling, laden with their own crimes and with those of their posterity. This portentous and savage monster, the power of the Saracens and the Turks, had it not been clipped and checked by our Military Orders, our Princes and Peoples, so far as Luther was concerned (to whom Solyman the Turk is said to have written a letter of thanks on this account), and so far as the Lutheran Princes were concerned (by whom the progress of the Turks is reckoned matter of joy), – this frantic and man-destroying Fury, I say, by this time would be depopulating and devastating all Europe, overturning altars and signs of the cross as zealously as Calvin himself. Ours therefore they are, our proper foes, seeing that by the industry of our champions it was that their fangs were unfastened from the throats of Christians.

HAERETICI. – Let us look down on heretics, the filth and fans and fuel of hell[6] the first that meets our gaze is Simon Magus. What did he do? He endeavoured to snatch away free will from man: he prated of faith alone (Clen. lib. i. recog.; Iren. l. 1, c. 2). After him, Novatian. Who was he? An Anti-pope, rival to the Roman Pontiff Cornelius, an enemy of the Sacraments, of Penance and Chrism. Then Manes the Persian. He taught that baptism did not confer salvation. After him the Arian Aerius. He condemned prayers for the dead: he confounded priests with bishops, and was surnamed “the atheist” no less than Lucian. There follows Vigilantius, who would not have the Saints prayed to; and Jovinian, who put marriage on a level with virginity; finally, a whole mess of nastiness, Macedonius, Pelagius, Nestorius, Eutyches, the Monothelites, the Iconoclasts, to whom posterity will aggregate Luther and Calvin. What of them? All black crows,[7] born of the same egg, they revolted from the Prelates of our Church, and by, them were rejected and made void.

Let us leave the lower regions and return to earth. Wherever I cast my eyes and turn my thoughts, whether I regard the Patriarchates and the Apostolic Sees, or the Bishops of other lands, or meritorious Princes, Kings, and Emperors, or the origin of Christianity in any nation, or any evidence of antiquity, or light of reason, or beauty of virtue, all things serve and support our faith.

SEDES APOSTOLICA. – I call to witness the Roman Succession, “in which Church,” to speak with Augustine (Epist. 162: “Doctr. Christ”. ii. 8), “the Primacy of the Apostolic Chair has ever flourished”. I call to witness those other Apostolic Sees, to which this name eminently belongs, because they were erected by the Apostles themselves, or by their immediate disciples.