I DO. As someone who suffers from MDD – Major Depressive Disorder, diagnosed in 1994, having had three major episodes, only medication and therapy having prevented more, and told I should expect at least six in my life, and takes daily meds and weekly therapy, I can relate. The experience is of excruciating emotional pain, laying on the couch not wanting to breathe, feeling the ground fall away from underneath your feet, moaning and writhing in a recliner at your in-laws. You just want the pain to stop. You don’t care how. You lose all perspective on how any decision you make will affect others. You just want the pain to stop. You don’t care how.

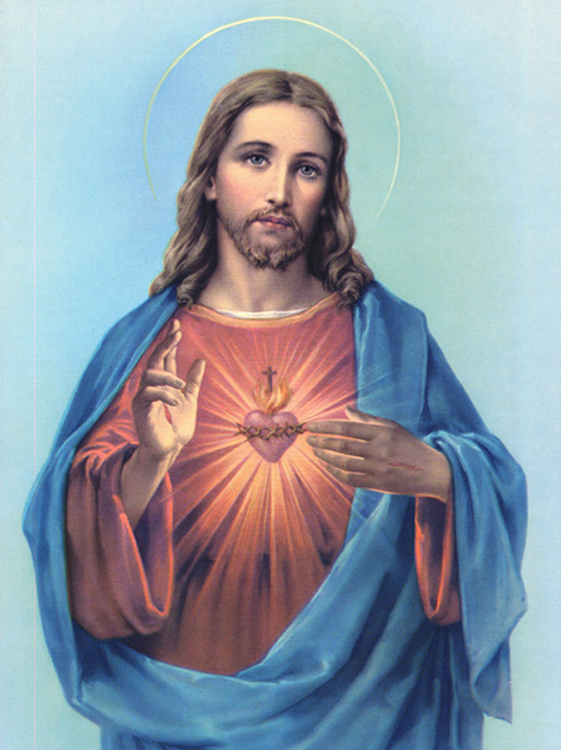

“The LORD is my strength and my shield; my heart trusts in Him, and He helps me. (He does.) My heart leaps for joy, and with my song I praise Him.” -Ps 28:7

Don’t take symptoms lightly. Get help. 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

“The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently found that suicide rates in the U.S. spiked between 1994 and 2014. While women are less likely to kill themselves than men, their rate of suicide jumped by 80 percent over this period. But not all women are at risk.

A study released this week by JAMA Psychiatry, an American Medical Association journal, reported that “Frequent religious service attendance was associated with substantially lower suicide risk among U.S. women compared with women who never attended religious services.” To be exact, the researchers studied approximately 90,000 nurses, mostly women, and found that Catholic and Protestant women had a suicide rate that was half that for women as a whole.

Of the nearly 7,000 Catholic women who went to Mass more than once a week, NONE committed suicide. Overall, practicing Protestant women were seven times more likely to commit suicide than their Catholic counterparts, suggesting there really is a Catholic advantage. Indeed, the 2015 book, The Catholic Advantage, substantiates this finding.

Today, those without a religious affiliation have the highest suicide rates, illustrated most dramatically in San Francisco: someone jumps off the Golden Gate Bridge to his death every two weeks. It is not the faithful who are waiting in line to jump—it’s the non-believing free spirits.

On a related note, Gallup released a survey yesterday (6/29/16) that shows approximately 9 in 10 Americans believe in God. But as we learned from the JAMA Psychiatry study, only those who regularly attend religious services are less likely to commit suicide.

In other words, mere belief, and amorphous expressions of spirituality, aren’t enough to ward off the demons that trigger suicide. And no group is more at risk than atheists.”

Freakonomics – Suicide

Internet Broadcast

-by Stephen J. Dubner

“Suicide rates in the U.S., they’re the highest they’ve been in 30 years.

Our latest Freakonomics Radio episode is called “The Suicide Paradox (Rebroadcast).” (You can subscribe to the podcast at iTunes or elsewhere, get the RSS feed, or listen via the media player above.)

There are more than twice as many suicides as murders in the U.S., but suicide attracts far less scrutiny. Freakonomics Radio digs through the numbers and finds all kinds of surprises.

Below is a transcript of the episode, modified for your reading pleasure. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post. And you’ll find credits for the music in the episode noted within the transcript.

* * *

Today we are playing an episode from our archives — an important episode, called “The Suicide Paradox.” We first put this out in 2011. Now, five years later, suicide rates in the U.S. have risen to their highest in 30 years, with suicide a particularly pressing problem in the military. We’ll be back next week with a new episode.

* * *

DAN EVERETT: There won’t be a word for college or professor, but I can say, “Tíi kasaagá Paóxaisi. Ti kapiiga kagakaibaaí.” And that just means, “my name is Paoxaisi, and I make a lot of marks on paper.”

Dan Everett is a college professor — a linguist. Off and on for the past 30 years, he’s lived with a tribe in the Amazon called the Piraha.

EVERETT: I originally went to the Piraha as a missionary to translate the Bible into their language, but over the course of many years, they wound up converting me, and I became a scientist instead and studied their culture and its effects on their language.

The Piraha live in huts, sleep on the ground, hunt with bows and arrows. But what really caught Everett’s attention is that they are relentlessly happy. Really happy.

EVERETT: This happiness and this contentment really had a lot to do with me abandoning my religious goals, and my religion altogether, because they seemed to have it a lot more together than most religious people I knew.

But this isn’t just another story about some faraway tribe that’s really happy even though they don’t have all the stuff that we have. It’s a story about something that happened during Everett’s early days with the tribe. He and his wife and their three young kids had just finished dinner. Everett gathered about 30 Piraha in his hut to preach to them:

EVERETT: I was still a very fervent Christian missionary, and I wanted to tell them how God had changed my life. So, I told them a story about my stepmother and how she had committed suicide because she was so depressed and so lost. (For the word “depressed” I used the word “sad”.) So she was very sad. She was crying. She felt lost. And she shot herself in the head, and she died. And this had a large spiritual impact on me, and I later became a missionary and came to the Piraha because of all of this experience triggered by her suicide. And I told this story as tenderly as I could and tried to communicate that it had a huge impact on me. And when I was finished everyone burst out laughing.

* * *

EVERETT: When I asked them, “why are you laughing?,” they said: “She killed herself. That’s really funny to us. We don’t kill ourselves. You mean, you people, you white people shoot yourselves in the head? We kill animals, we don’t kill ourselves.” They just found it absolutely inexplicable, and without precedent in their own experience that someone would kill themselves.

In the 30 years that Everett has been studying the Piraha, there have been zero suicides. Now, it’s not that suicide doesn’t happen in the Amazon – for other tribes, it’s a problem.

EVERETT: And as I’ve told this story, some people have suggested that, well it’s because they don’t have the stresses of modern life. But that’s just not true. There is almost 100 percent endemic malaria among the people. They’re sick a lot. Their children die at about 75 percent. Seventy-five percent of the children die before they reach the age of five or six. These are astounding pressures.

MUSIC: Matthew Reid, “Quietus” (from Courtyards and Fairgrounds)

A group of people that laughs at suicide? Doesn’t sound much like the U.S., does it? Suicide’s not a laughing matter here; and it’s not so rare, either. Now, compared to the rest of the world, our suicide rate puts us right about in the middle. But here’s what’s interesting. The U.S. is famous for a relatively high murder rate – it’s double, triple, even five times higher than most other developed countries. So if I said to you: what’s more common in the U.S., homicide or suicide, what would you say?

Listen to Steve Levitt, my Freakonomics friend and co-author, an economist at the University of Chicago. He’s been studying crime for years.

STEVE LEVITT: Homicides, per one hundred thousand, have fallen from something like ten to something like five over the 15 years I’ve studied crime. So essentially, homicide has fallen in half.

STEPHEN J. DUBNER: Wow, so let’s say it’s roughly five per hundred thousand people now, do you have any idea what the suicide rate is?

LEVITT: That’s about twice as high. It’s surprising because it doesn’t usually make the newspaper when someone commits suicide, but it always makes the newspaper when someone commits a homicide, but twice as many suicides as homicides.

It is surprising, isn’t it? The preliminary numbers for 2009, the most recent year for which we have data, show there were roughly 36,500 suicides in the U.S. and roughly 16,500 homicides. That’s well over twice as many suicides. So why don’t we hear more about it? Partly because, as Levitt says, most suicides don’t make the news, whereas murders do. But also: they’re different types of tragedy. Murder represents a fractured promise within our social contract, and it’s got an obvious villain. Suicide represents – well, what does it represent? It’s hard to say. It carries such a strong taboo that most of us just don’t discuss it much. The result is that there are far more questions about suicide than answers. Like: do we do enough to prevent it? How do you prevent it? And the biggest question of all: why do people commit suicide? Steve Levitt has one more question:

LEVITT: I always think to myself: why don’t more people commit suicide? If you think about the poorest people in the world surviving on less than a dollar a day, having to walk three miles to get water and carry 70-pound packs of water back just to survive, and those people do everything they can to stay alive. Whereas I think if I were in that situation, wouldn’t I just kill myself?

DUBNER: And what does that say to you about human nature that people in situations way, way, way, way, way worse off than you don’t kill themselves in large number?

LEVITT: My guess is that evolution has built in to us an unbelievable desire to stay alive, which when looked at from a modern perspective doesn’t actually make that much sense.

So how should we make sense of suicide? If you, personally, have been affected by suicide, if you’ve lost a friend or family member, it may be hard to even think about “making sense” of it. But, at the risk of shining a light into a darkness that’s usually left undisturbed, let’s give it a try. The first thing we need is a Virgil of some sort to guide us —someone who’s been thinking about suicide, and death, for a long, long time.

DAVID LESTER: I was born in 1942. I lived in London for 22 years of my life. And for the first three years of my life, my mother told me we slept in an air raid shelter every night.

David Lester is a professor of psychology at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, about 20 minutes from Atlantic City.

LESTER: The classic bomb that came over was called a buzz bomb because it was buzzing and that meant that the engine was going. Once it stopped buzzing it meant it would drop and maybe hit your house. My mother says that even as a toddler, I was very concerned about them. And actually she said that I would hear them before the air raid warnings went off, and I would warn everybody about a buzz bomb, and I would rush into the air raid shelter. Then 10 years ago, I remembered this picture of this little toddler who’s very worried about buzz bombs and hiding from them probably without a material concept of death, but obviously perhaps, laying the seeds of some interest that manifested itself later in life. I’ve become a thanatologist in general, and a suicidologist in particular.

Lester is president-elect of the American Association of Suicidology, and the eminence grise of suicide studies. He’s also alarmingly prolific — he’s written more than 2,500 papers, notes, and books, about half of which are on suicide. So people expect him to know things that he says are not yet known.

MUSIC: Abstract Aprils, “Parallels” (from Translucence)

LESTER: First of all, I’m expected to know the answers to questions such as why people kill themselves. And myself and my friends, we often, when we’re relaxing admit that we really don’t have a good idea of why people kill themselves.

So what do we know about suicide? As you drill down into the numbers, one thing that strikes you are the massive disparities — the difference in suicide rates by gender, by race and age, by location, by method and many other variables. In the U.S., for instance, men are about four times as likely to kill themselves as women.

LESTER: Yes, about three to four, yes.

About 56 percent of men use a gun, compared to just 30 percent of women.

LESTER: Yes, men tend to use what we would call more active methods.

That helps explain the gender gap, since suicide by gun is usually successful. The primary method for women is technically called “poisoning” – usually some kind of overdose.

LESTER: The easy access to medications these days makes medications an important method.

For men and women, being unmarried, widowed or divorced increases the risk. The most typical American suicide is a man 75 or older. But in that age bracket, where a lot of people are dying from a lot of things, suicide isn’t even a top 10 cause of death. For people from ages 25 to 34, suicide is the second leading cause of death. And it’s in the top five for all Americans from ages 15 to 54. In terms of timing, suicide peaks on Mondays:

LESTER: There is a blue Monday effect.

But not, as many people suspect, around Christmas and New Year’s.

LESTER: People do not kill themselves more on national holidays.

There is a seasonal spike, but it’s not in the long, dark days of winter.

LESTER: In fact, suicide rates peak in the spring in most countries. It’s as if you expect things are going to be better, and when they turn out not to be better, you’re more likely to be depressed in a suicidal way.

David Lester is willing to entertain any theory, to examine any pattern. Interestingly, he’s found that suicide and homicide are often perfectly out of synch with each other. Homicide spikes not on Mondays but on the weekends and on national holidays and during the summer and winter. Homicide is also much more common in cities than in rural areas; for suicide, it’s the opposite.

MATT WRAY: The American suicide belt is comprised of about 10 western states, this sort of wide longitudinal swath running from Idaho and Montana down to Arizona and New Mexico.

That’s Matt Wray, a sociologist at Temple.

WRAY: To sum up what I do in a word would be to say that I study losers. And I am interested in those who lose out on societal gains and opportunities. It’s another way of saying I’m interested in inequalities and stratification.

Wray found what he has taken to calling the “Suicide Belt.”

WRAY: So, yes, the inner mountain west is a place that is disproportionately populated by middle-aged and aging white men, single, unattached, often unemployed with access to guns. This may turn out to be a very powerful explanation and explain a lot of the variance that we observe. It’s backed up by the fact that the one state that has rates that is on par with what we see in the suicide belt is Alaska.

Alright, so now you can get a picture of the American who’s most likely to kill himself: an older, white male who owns a gun, probably unmarried and maybe unemployed, living somewhere out west, probably in a rural area. Now, don’t you want to know: where aren’t people killing themselves?

VERALYN WILLIAMS: OK, so I’m standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

Washington, D.C., our nation’s capital. It’s got the lowest suicide rate of any American city: just six per 100,000 people. We sent Veralyn Williams there to ask strangers a couple of strange questions.

WILLIAMS: Do you know anyone that committed suicide?

TYRONE: Personally no.

AMINA: No.

WILLIAMS: Do you know anyone that’s died of homicide?

AMINA: Yes.

SAMIAR: Yes, I do.

BARNES: I got a son that’s been murdered. I’ve got cousins that’s been murdered. I’ve probably been to 100 wakes in the past year. But I can’t tell you one person that I know that’s committed suicide.

Now, as we told you earlier, there are more than twice as many suicides each year in the U.S. as there are homicides. There are just three places where the homicide rate is higher than the suicide rate: Louisiana, Maryland, and the District of Columbia. It’s not a coincidence that these are also places with large African-American populations. African-Americans are only about half as likely to kill themselves as whites. When it comes to murder, meanwhile, African-Americans are nearly six times more likely than whites to die.

DONNA BARNES: In our community, it’s different. We have low rates of suicide and high rates of homicide.

WILLIAMS: Why do you think that is?

BARNES: I think a lot of those homicides are probably suicides.

Donna Barnes works at the suicide prevention center at Howard University.

BARNES: It’s very easy when you are stressed and you don’t want to live anymore and put yourself in harm’s way and somebody will take you out. And many times, we will externalize our frustration, meaning that we’re going to take it out on other people. And then you might have more folks, maybe from the dominant culture, who internalize their frustration and take it out on themselves. We have been socialized to believe that a lot of our disadvantages are based on our surroundings — racism, discrimination and all of that. So it’s really easy, for us, when we become frustrated and we look at what’s going on around us, to take it out on the environment and other people rather than ourselves.

I asked David Lester if he had an explanation for the black-white suicide gap.

LESTER: If you’re white and in psychological pain, what can you blame it on? Other people are doing well, why aren’t you doing well? Other people are happy why aren’t you happy? So maybe that, in part, accounts for the higher suicide rate in whites as compared to African-Americans is because whites have fewer external causes to blame their misery for.

MUSIC: Morrison 78s, “Goodbye Little Girl Goodbye”

I find this idea fascinating. As Lester is quick to point out, it is little more than an idea – it’s pretty much impossible to prove. The fact is, we usually don’t know much about what’s going through a person’s mind as they consider suicide. But when your life is miserable, when it seems beyond redemption or repair, where do you put the blame? You can blame other people. You can blame yourself. What if you could blame … a song?

* * *

As we said earlier, there are about 36,500 suicides a year in the U.S. That’s an average of 100 a day. The vast, vast majority of them, you never hear about. They don’t make the news. That’s not an accident. For decades, sociologists have been studying the media’s impact on suicide rates. And some say they’ve proven that a widely publicized suicide – when described in a certain way – can lead to copycat suicides. A suicide contagion.

SEAN COLE: All right so we’re gonna have to go all the way back to 1774… when this novel came out.

READER: The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. May 4. How happy I am that I am gone! My dear friend, what a thing…

COLE: For those of you who have never read it – I had never read it – “The Sorrows of Young Werther” is written mostly as a series of fictional letters by a young, dilettante artist named Werther. He travels to the countryside, falls in love with a girl who’s already engaged, despairs, and then borrows two pistols from her fiancé.

READER: “They are loaded. The clock strikes twelve. I say Amen! Charlotte! Charlotte! Farewell! Farwell!”

COLE: Sorry to spoil the ending. Now, this book was really popular when it came out. Scholars talk about legions of men in Europe dressing like the character, in blue swallowtail coats and canary yellow pants. And while this next part is probably apocryphal, the story goes that…

DAVID PHILLIPS: Many people who read the book killed themselves by the same method and sometimes they even killed themselves with the book open to the page where he was described as killing himself.

COLE: David Phillips is a sociology professor at U.C. San Diego and the father of imitative suicide research in America. In 1974, exactly 200 years after Werther was published, he released a seminal paper called, “The Influence of Suggestion on Suicide: Substantive and Theoretical Implications of the Werther Effect.”

PHILLIPS: My students and I were the first to provide modern large scale evidence that there is, in fact, such a thing as copycat suicide. And we called this, I called it, the Werther Effect.

COLE: Now, Werther is a work of fiction. But the Werther Effect focuses more on true stories about suicide. The theory goes that whenever the media runs with a big sensational suicide story, especially if the victim is famous, you can expect a bump in suicide rates. Phillips and company gathered 20 years of suicide data, 1948 to 1967, from The National Center for Health Statistics. Then they combed through back issues of three major newspapers and honed in on front-page suicide reports: the actress Carole Landis; Dan Burros who ran the KKK in New York; one of the most famous stars in Hollywood history.

NEWS REPORT: One of the most famous stars in Hollywood history is dead at 36. Marilyn Monroe was found dead in bed.

COLE: Of course, this was back before all of the conspiracy theories about how she died. Anyway, in 27 out of 33 cases like this: suicide rates were higher than expected for about two months following the story. So for example, Marilyn Monroe died on August 5, 1962. For the rest of that August, U.S. suicide rates were 10 percent higher than normal.

PHILLIPS: How do we know that there’s a 10 percent increase in August of ’62. We’re comparing the number of suicides in August of ’62 with the number of suicides in August of 1961 and the number of suicides in August of 1963.

COLE: So those other Augusts are the controls.

PHILLIPS: That’s right.

COLE: In some cases, the bump was a lot smaller. But it’s not so much the size, says Phillips, as the consistency. And it wasn’t just suicides that went up after these media reports.

PHILLIPS: You also get a spike in single-car crashes after suicide stories. And you see that the driver in the single car crash is unusually similar to the person described in the suicide story. So if the person described in the suicide story is unusually young, then the spike in single-car crashes just afterwards has drivers who are unusually young.

COLE: So to close that loop — they’re not accidents. They’re people who are committing suicide.

PHILLIPS: Right. So all of these things together make it very difficult to think of an alternative explanation.

COLE: But this is not to say people kill themselves because they read a big, splashy suicide story in the paper.

THOMAS NIEDERKROTENTHALER: It’s not really about the causes of suicide. It’s about the trigger of suicides.

COLE: This is Thomas Niederkrotenthaler, an assistant professor at The Medical University of Vienna in Austria. About 10 years after that original study, the Werther Effect hit Vienna in a big way.

NIEDERKROTENTHALER: There was a tremendous increase of subway suicides and suicide attempts on the Viennese subway in the early 1980’s.

COLE: In 1983 there was just one jumper in the Viennese subway and that person lived. The next year there were seven suicides by subway in Vienna. And the big Austrian newspapers ran graphic stories about them. 1985, 13 jumpers, 10 deaths, more splashy articles. At the peak, in 1987, there were 11 successful suicide attempts in the Viennese subway and 11 unsuccessful. Though granted, three of those were the same guy. Finally, the Austrian Association of Suicide Prevention told the press to tone it down. They issued a whole series of recommendations: don’t include the word “suicide” in the headline. Don’t print pictures of grieving relatives.

NIEDERKROTENTHALER: But you should also mention help-lines. Helping opportunities for people in crisis.

COLE: Amazingly, the Austrian media listened. The stories were less graphic, and they stopped running so many of them.

NIEDERKROTENTHALER: And at the same time the number of suicides and suicide attempts on the Viennese subway decreased by nearly 80 percent. And this is really stunning— the numbers remained relatively low in all the years up until today.

PHILLIPS: Yeah, I thought that was a pretty study.

COLE: This is David Phillips again. He says he’s actually not so comfortable telling the media what to do. He thinks freedom of the press should be inviolate. But both the World Health Organization and the AP Managing Editors Association asked for his advice. So he basically told them, ‘Think of a suicide story as a kind of commercial. If you make the product attractive, people will want it.’ But if you say…

PHILLIPS: “By the way, when a person kills himself, let’s say by shooting, he looks terrible afterwards.” Or, “When a person poisons himself, he often fouls the bed sheets.” And things like this. If you talk about the pain and the disfigurement, then I thought that would make it less likely that people would be copying the suicide.

COLE: And there may even be a trend growing in the other direction. Thomas Niederkrotenthaler and his team in Austria did their own study looking at nearly 500 newspaper articles from the first half of 2005. He says not only did they find more evidence for the Werther Effect, but they saw suicide rates go down when the media wrote about someone who found an alternative solution to his or her problems.

NIEDERKROTENTHALER: So this may be exactly the opposite side of the same thing. And we called this effect: the Papageno Effect.

COLE: Papageno is another fictional character, from Mozart’s opera “The Magic Flute.” Like Werther, he’s in suicidal crisis over a girl, his beloved Papagena. But just as he’s about to hang himself, three young boys rush the stage and tell him not to do it. They say…

NIEDERKROTENTHALER: “Papageno use your magic bells and Papagena will come back.” And psychologically speaking, we can say this is what we believe that those newspaper or press articles do. They remind people what they can do other than commit suicide.

WRAY: Now I should say that I’m pretty agnostic about this. My sense is that what this literature misses are all of the times that high profile suicides occur that don’t spark contagion. The one that comes to mind is Kurt Cobain. So everyone was expecting a rash of shotgun-induced, blow-your-head-off suicides in the wake of Cobain’s death. They did not materialize. And so the question is…

NIEDERKROTENTHALER: Why was it so? There was some specifics about Kurt Cobain’s suicide. In particular, Cobain’s spouse…

COLE: Courtney Love. Yeah.

NIEDERKROTENTHALER: Yeah, Courtney Love. She was broadcast in the media immediately after his suicide.

COURTNEY LOVE: I’m really sorry you guys. I don’t know what I could have done.

NIEDERKROTENTHALER: And she told to the audience this was really the wrong thing to do. And there is one study, actually from the U.S., which showed that reports that use negative definitions of suicide — so such as suicide is something that is stupid that you should not do— that those reports are 99 percent less likely to identify a copycat phenomenon than other reports.

COLE: So, listen, suicide is something is stupid, that you should not do. After all, I am the media. And this whole show is basically one big suicide article. And as I said to Matt Wray, I’ve been wondering which type of article it is.

WRAY: Are you guys trying to figure out how to report on this story without, like, sparking suicides?

COLE: Well, it is an odd little meta problem isn’t it. I mean, I’m doing a story about whether what I’m doing a story about could possibly cause a suicide contagion.

WRAY: Yes, I’m well acquainted with that dilemma.

* * *

But what about a song? David Lester, the psychology professor, tells us about the time…

LESTER: In the 1930s, two Hungarians wrote a song called “Gloomy Sunday” that was thought to precipitate a wave of suicides across Europe.

Freakonomics Radio producer Suzie Lechtenberg went to Hungary.

SUZIE LECHTENBERG: Rezso Seress’ piano still sits, rather benignly, in the restaurant in Budapest where he used to play his most famous song. The person in the song is thinking about suicide. He, or she, wants to be reunited with a lover who has just died. Today, it sounds a bit melodramatic, but as many as 200 people might have killed themselves after listening to this song.

ZOLTAN RIHMER: Yes, yes, yes, yes.

LECHTENBERG: Because they heard the song?

RIHMER: Yeah. But it was just the trigger.

LECHTENBERG: It was just the trigger, Hungarian psychiatrist Zoltan Rihmer says. But it had to be stopped. The Budapest police enforced a Gloomy Sunday ban. And the BBC…

LESTER: The BBC banned that song until 2002.

LECHTENBERG: These days, the owner of the restaurant where Seress used to play, still gets requests. He’s not afraid to play it. But he feels certain that this was a suicidal song. It should come as no surprise then…

RIHMER: Rezo Seress completed suicide. He was around 70.

LECHTENBERG: In 1968, Rezo Seress — Gloomy Sunday’s composer — jumped to his death from the window of his small apartment in Budapest. Unfortunately, this Hungarian suicide story isn’t unique to this one man, or this one song. Suicide has been epidemic in this country. For most of the last century, Hungary has had the highest suicide rate in the world. Right now, it’s more than double the suicide rate in the United States. So what is it about this place? Why are so many people killing themselves here?

SZILVIA LADONMERSZKY: Oh, my husband. My husband was very handsome. Great looking. Very intelligent.

LECHTENBERG: Szilvia and Levente Ladomerszky met at a concert. He was a neurologist, she worked in finance. He was cool, she says. They fell in love. Married. Had a daughter. But they didn’t have a fairy tale ending. Levente’s family had a history of mental illness. It was something he was afraid was in his blood.

LADONMERSZKY: Before we married, were sitting at the kitchen table, and he told me that, if it ever happens to him, that he gets ill, and he will need treatment with drugs, then he will refuse the drugs. And he will never take drugs, he prefers dying because drugs, psychiatric drugs, will change personality and he wants to remain himself all the time.

LECHTENBERG: Levente’s mental state deteriorated. He was hospitalized.

LADONMERSZKY: And a few years after, it happened to him exactly what he described.

LECHTENBERG: When he had a few moments alone, when the doctors and nurses left his room, Levente Ladomerszky hanged himself.

LADONMERSZKY: My own suicide I was able to completely ignore, but my husband’s is somehow still with us.

LECHTENBERG: “My own suicide was something I was able to completely ignore.” Szilvia tried to kill herself years before she and Levente met. But she says, she didn’t want to die. It was a cry for help more than anything else.

LADONMERSZKY: I took a bunch of pills, but made sure that it won’t kill me.

LECHTENBERG: Everyone in Hungary knows someone like Szilvia, like Levente. The World Health Organization says in 2008, about 2,400 people committed suicide here. To put that number in context, around the same time in Greece, a country that’s roughly the same size, there were 394 suicides.

RIHMER: Yes, my name is Zoltan Rihmer.

LECHTENBERG: I met Dr. Zoltan Rihmer in his smoke-filled office in Budapest. He’s a professor of psychiatry at Semmelweis University, and he says, there are two main reasons the suicide rate is so high.

RIHMER: The prevalence of bipolar disorder. We have found the lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder in Hungary is five percent.

LECHTENBERG: The worldwide rate of bipolar disorder is about half that.

RIHMER: The risk of suicide is much higher among patients with bipolar disorder. It can be one factor. But it is just one factor. Alcohol. Alcohol plays a very important role in suicide.

LECHTENBERG: And Hungary has the third highest alcohol consumption rate in the world. This country is about the size of Indiana. From the window of a train, the Hungarian Great Plains look like it too. In the southwest, there’s a small town called Kiskunhalas.

KATALIN SZANTO: It’s a nice little town.

LECHTENBERG: That’s psychiatrist Katalin Szanto.

SZANTO: So, there is a little lace museum there, and there are these women making beautiful laces. On the other hand, if you walk around, you see drunken people outside the pubs. If you visit the local hospital in the psychiatric ward, there the circumstances were very, very poor.

ÁGNES RACZ NAGY SPEAKING IN HUNGARIAN through TRANSLATOR: My name is Dr. Ágnes Rácz Nagy, and I’m the leader of this psychiatric department of the Kiskunhalas hospital.

LECHTENBERG: Until 2005, Kiskunhalas was the epicenter of suicide in Hungary. Suicide in this town was double the national rate. As one cultural critic put it, living here, was like living on psychic death row.

NAGY: I’ve seen a family — it was a big family — and there were more than 10 suicides in the family.

LECHTENBERG: In 2001, Dr. Agnes Rácz Nagy and a colleague began 100 “psychological autopsies,” meaning, they interviewed families, in depth, after a loved one committed suicide.

NAGY: In 67 there was mood disorder, and 60 alcohol. And of course there were overlaps as well. But this number is huge.

LECHTENBERG: This was part of a study that ran for five years in Kiskunhalas. Dr. Katalin Szanto and colleagues trained 28 of the town’s 30 general practitioners in suicide prevention. They set up a suicide hotline, and made low-cost anti-depressants available to residents. Then they compared their results to a neighboring town — a control group. And it worked.

SZANTO: Yeah, there were, like, 34 less suicides during these five years than in the previous five years.

LECHTENBERG: Overall, the suicide rate in the region decreased sixteen percent. The suicide rate for women decreased 34 percent. This shouldn’t be that surprising. Research by academics in the United States, like Jens Ludwig, has shown that anti-depressants do lower the suicide rate. But here’s the thing: even though the suicide prevention program in Kishkunhals was a success, this model just hasn’t caught on elsewhere in Hungary. The country still has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. So, why?

BELA BUDA: Well, we can see a part of the bridge, the Margaret Bridge.

LECHTENBERG: Back in Budapest, everywhere you walk, there are musicians playing classical music in the streets. The Margaret Bridge stretches over the Danube, which is the lifeblood of this city. It’s stunning, but it’s also the place where many Hungarians have jumped to their death. I met psychiatrist Bela Buda on the banks of the river.

BUDA: I am 73. I was born and lived in Budapest in all my life.

LECHTENBERG: He looks exactly how you want someone named Buda to look: graying, rotund. I’ve been told he speaks 17 languages. He says it’s just 12. Buda has tried to solve the problem of suicide his entire career. He started the first suicide hotline in the country; he worked in psychiatric wards when the suicide rate was soaring. But, he says, this problem is hard to solve, because a lot of people here don’t see anything wrong with suicide.

BUDA: The Hungarian general opinion is very favorable towards suicide. If somebody commits suicide, then it is commented as a brave act. That somebody had the courage to end suffering. For instance, these old men who hang themselves are praised in the community that he was brave enough to free the family from the burden of his existence.

* * *

Next year, the Golden Gate Bridge will celebrate its 75th anniversary. You’ll hear all kinds of tributes to it, all kinds of facts and figures. One number you probably won’t hear, at least in the official proclamations, is the suicide toll: since the Golden Gate Bridge opened, more than 1,400 people have killed themselves by jumping off it.

There is another place that now attracts more suicides each year — the Aokigahara Forest in Japan – but, historically, the Golden Gate is still the world’s No. 1 suicide spot. Last year alone, 32 people jumped and died. Now, it should be said that every weekday, about 5,000 people walk across the bridge and don’t jump. And 100,000 cars cross it every day.

TAXI DRIVER: My name is (name in Thai). That’s 17 letters all together.

He moved here from Thailand in 1968, and he drove a cab in San Francisco for 15 years.

TAXI DRIVER: One night I picked up a guy, I think down nearby Tenderloin, and he want to go Golden Gate bridge. Must be 11 o’clock at night. And I said “OK,” so I drove on Franklin Street. He said, “You want to ask me why I go to Golden Gate Bridge this late?” I said, “No, but if you want to tell me, I guess I will listen to it.” And he said “I’m going to go and jump off the Golden Gate Bridge.” And I said, “OK.” “You’re not going to stop me?” I said, “Why should I?” So I get out to the Golden Gate Bridge, I think the fare was like $7 or something at that time. And he looked in his wallet and found $10, so he give it to me, the $10. So I told him, “I don’t think you need any change.” He said “I guess you’re right, I don’t need any change.” So, I let him off at the side of the bridge, and once he get off, I turned around the cab and called my dispatcher. I told him, “Why don’t you call the harbor patrol there?” And he did. Maybe, I don’t know, maybe I was too cool to him. I don’t know what happened— if he was really going to jump.

Now, we don’t know if this man did, in fact, jump off the Golden Gate Bridge that night. If he did, he almost certainly died, since only two percent of jumpers survive. We also have no idea what was going through his head that night. Did he have a fight with someone? Did he lose his job? Did he maybe just have one drink too many?

LESTER: I’m expected to know the answers to questions such as why people kill themselves.

If you unpack that “why” in “why people kill themselves,” there are all kinds of other things we don’t know about suicide either. For instance: the percentage of people who seek help, or get help, before committing suicide. We don’t know. Or even how many people who commit suicide are mentally ill. Lester says there is so much disagreement on this question that estimates range from five percent to 94 percent. And then there’s the mystery of the suicidal impulse.

LESTER: And I just found a case, which I’m using in an article that I’m writing, where the time between the impulse and the act was something like five seconds.

Think about that: five seconds.

LESTER: The man was walking over a bridge, and suddenly the thought came to him.

One.

LESTER: He was in some, I think, financial distress,

Two.

LESTER: But he hadn’t thought about suicide before.

Three.

LESTER: And he said, I ought to kill myself.

Four.

LESTER: And he immediately jumped off the bridge.

Five.

LESTER: And he was saved. And that’s the shortest interval I’ve come across.

One academic study looked at attempted suicides in Houston among 15-to-34-year-olds. It found that in 70 percent of the cases, the time between deciding to commit suicide and taking action was under an hour. Seventy percent of the cases. For about one-quarter of the people involved, the time gap was five minutes or less. That’s pretty stunning. People are making a permanent decision to end their lives, on the spur of the moment. How are you supposed to stop that? Remember this guy?

TAXI DRIVER: My name is (name in Thai).

He didn’t try to stop his taxi passenger from jumping.

TAXI DRIVER: “You’re not going to stop me?” I said, “Why should I?”

“Why should I?” Sounds cold-hearted, doesn’t it. Or does it? Your life belongs to you. It’s a crime to take someone else’s life. But not yours, at least not a crime in practice. So: should we consider the suicidal impulse a rational choice? I know what you’re thinking: only an economist would say something like that, an economist like Dan Hamermesh, at the University of Texas. He once wrote a paper called “An Economic Theory of Suicide.”

DAN HAMERMESH: Well, I think there’s an epigraph to the paper, which I cannot quote exactly, it’s by Arthur Schopenhauer: “When the value of a man’s life is less…” You can read it there, I don’t have it with me, now. Why don’t you read it.

DUBNER: “As soon as the terrors of life reach the point at which they outweigh the terrors of death, a man will put an end to him life.”

HAMERMESH: Exactly. Well, that’s just an economic statement. You’re weighing the benefits on one side of the equation, the costs of the other. If the costs exceed the benefits, you chop off the investment.

Back in the spring of 1972, Dan Hamermesh was hunting around for a research topic. And he thought of a poem he’d read back in high school.

HAMERMESH: The poem is “Richard Cory” by Edwin Arlington Robinson, written in the last decade of the nineteenth century. “Whenever Richard Cory went downtown, we people on the pavement looked at him…

There was something about the poem that nagged him.

HAMERMESH: …and he was rich, yes richer than the king, and admirably schooled in every grace. In fine, we thought that he was everything to make us wish that we were in his place. So, on we worked and waited for the light, and went without the meat, and cursed the bread. And Richard Cory, one calm summer night went home and put a bullet in his head.”

That’s it, the last part. It didn’t make sense to him.

HAMERMESH: I was always very bothered by the notion that suicide’s a problem of rich people. And that always struck me, as an economist, as being really stupid since rich people are generally going to be happier, utility is higher, income goes up, you should be less likely to kill yourself. So those were the thoughts running through my mind that spring afternoon of 1972.

So Dan Hamermesh did what economists do. He wrote a model to determine the conditions under which suicide might be considered a rational choice. He came up with three predictions. Suicide, one, rises with age; two, falls as income increases; and three, falls if your “desire to live” is high. Nothing so radical, but at the time, no one had tried anything like this.

Then, Hamermesh plugged some suicide data from the World Health Organization into his model. His predictions were right. He also calculated the opportunity cost of a suicide. A 50-year-old person and a 70-year-old person have different expectations of future happiness, income, and so on. So the price of suicide is higher for the 50-year-old. But whether it makes economic sense for either person to commit suicide depends on what economists call the utility function – how much you value your life.

So it all goes back to the Schopenhauer quote at the beginning of Hamermesh’s paper: “as soon as the terrors of life reach the point at which they outweigh the terrors of death, a man will put an end to his life.” Hamermesh may have been the first economist to wrestle with suicide in this way, but he was hardly the first to intellectualize it:

MARGARET BATTIN: Plato, Aristotle, the Greek and Roman Stoics, the early Church Fathers on up to Durkheim and Freud.

Margaret Battin…

BATTIN: Sometimes called Peggy.

… is a professor of philosophy at the University of Utah. Plato, she says, argued that suicide was wrong in some cases, not wrong in others. Aristotle thought it was cowardly, an offense to society.

BATTIN: The Stoics, on the other hand, thought that suicide was the act of the wise man. This is not done in desperation or agitation or depression or any of the things that we ordinarily associate with that term, but it’s the reflective responsible act of the genuinely wise man.

For the Stoics, suicide was a procedure. People who wanted to commit suicide would plead their case before magistrates to get permission; the magistrates kept a supply of hemlock on hand.

READER: “Whoever no longer wishes to live shall state his reasons to the Senate, and after having received permission shall abandon life. If your existence is hateful to you, die; if you are overwhelmed by fate, drink the hemlock. If you are bowed with grief, abandon life. Let the unhappy man recount his misfortune, let the magistrate supply him with the remedy, and his wretchedness will come to an end.”

But going forward in history, this was hardly the mainstream view. Christianity held that suicide is a sin; Dante set aside one ring of his Inferno for suicides. Fast forward about 700 years, and we’re still firm in our moral stance. We can’t really consider suicide a rational choice, can we?

MARGARET HEILBRUN: We would wake up to the sound of her typing at an astonishing speed on her Smith Corona typewriter.

Margaret Heilbrun is talking about her mom. Carolyn Heilbrun was a Virginia Woolf scholar at Columbia; she wrote mystery novels on the side. She was famous for making grand pronouncements, for saying outlandish things.

MARGARET HEILBRUN: A partner of mine enjoyed drinking Stolichnaya vodka, so she took to having it on hand, but she insisted on calling it “Solzhenitsyn” vodka. And she knew it wasn’t, but she just, you know— “I’ll go get the Solzhenitsyn.” So, it was the same with her once she started saying that she would kill herself when she reached a certain age. But it was another one of those sort of pronouncements. And one thought, “oh well, Mommy’s prone to pronouncements.”

Carolyn Heilbrun had decided that, by the time she turned 70, she would have accomplished what she could accomplish; she would have had enough of life, and she’d end it. Her family – her husband and three grown kids – they weren’t quite sure what to make of this. It was a relief when her 70th birthday came and went without a suicide. Apparently she had changed her mind. She even wrote a book called The Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty. Her daughter says she took a lot of pleasure in life, even the small things.

HEILBRUN: She loved to get gifts. And it was quite easy to please her with a gift. And she’d made some sort of remark about she wanted to start listening to sextets, I think she said. No longer string quartets, no longer string quartets, I want quintets and sextets. And I was at Borders bookstore and found, could it have been a sextet by Elgar? And this was on Tuesday, the 7th of October. And I pulled out my cell phone to call her, and her voicemail came on, and I thought, “well I don’t really feel like talking to her right now.” I was going to call and say, “oh you don’t really want Elgar do you? You really want me to buy you Elgar?” And I hung up before she picked up, and I never spoke to her again.

Carolyn Heilbrun waited until she was 77, and then she did kill herself on October 9, 2003. She wasn’t sick; she wasn’t depressed. But she did feel she’d come to the end of her writing life. And that was that.

HEILBRUN: She left a note out in the foyer that said, “The journey is over, love to all. Carolyn.”

DUBNER: Did anyone know that she was planning to kill herself now? Did you father know, for instance?

HEILBRUN: Oh no, he didn’t know.

DUBNER: Your father — he was an economist, yes?

HEILBRUN: Yes.

DUBNER: So, economists are practiced in the art, or science, or whatever it is, of what’s known as rational thinking. Here is the wife of an economist, your mother, who seems to have approached suicide, at least life and the end of life, as a rational decision. Did you see it that way, or no?

HEILBRUN: No, I think it’s: if you’re mortally ill and in great pain, I can see seeking to end your life. But no, I think it was unreasonable, irrational of her. But, I think she felt it entirely reasoned out and rational.

DUBNER: Well, Margaret, I’m sorry for your loss and again, I very much appreciate your willingness to come speak to us.

HEILBRUN: Well, thank you.

For David Lester, the dean of suicide studies, 40-plus years of research has yielded some answers about the “what” of suicide – who’s most likely to do it, and when, and how. But the “why” remains elusive. The people who do it aren’t necessarily the ones you might expect.

Remember the point Steve Levitt made earlier in show – how puzzling it is that people whose lives look so hard don’t kill themselves in huge numbers? Remember the Piraha, the Amazonian tribe with their outrageous rates of infant mortality and malaria – but no suicide? Or African Americans, who trail white Americans on just about every meaningful socioeconomic dimension – but commit suicide half as often? Here’s what David Lester has been thinking about:

LESTER: Actually, I’ve done studies on the quality of life in nations and the quality of life in the different states in America. And regions with a higher quality of life have a higher suicide rate. Now, quality of life is more than wealth. The people who try and rate the quality of life use a variety of indices: health, education, culture, geography, all kinds of things. So they put more into it than just median family income, or individual per capita income. And what I’ve argued, therefore, is it seems to be an inevitable consequence of improving the quality of life. If your quality of life if poor— and it may be you’re unemployed, you’re an oppressed minority, whatever it might be, there’s a civil war going on, you know why you’re miserable — you know, as the quality of life in a nation gets better and you are still depressed – well, why? Everybody else is enjoying themselves, getting good jobs, getting promotions, you know, buying fancy cars. Why are you still miserable? So, there’s no external cause to blame your misery upon, which means it’s more likely that you see it as some defect or stable trait in yourself. And therefore you’re going to be depressed and unhappy for the rest of your life.

DUBNER: It’s so interesting. There are just so many pieces of this puzzle, as you put it, that are fascinating, but confounding. I mean, what you’re talking about now, when there’s a higher quality of life, suicide tends to rise. Your wife, who’s an economist, I wonder if she would consider then calling suicide to some degree a luxury good?

LESTER: Yes, now, there’s an anthropologist in the past, Raoul Naroll, who considers suicide an indication of a sick society. And so, in my writings I’ve argued that no, it’s an indication of a healthy society. So, it is a puzzle. There’s a paradox, perhaps we should say.”

Love,

Matthew