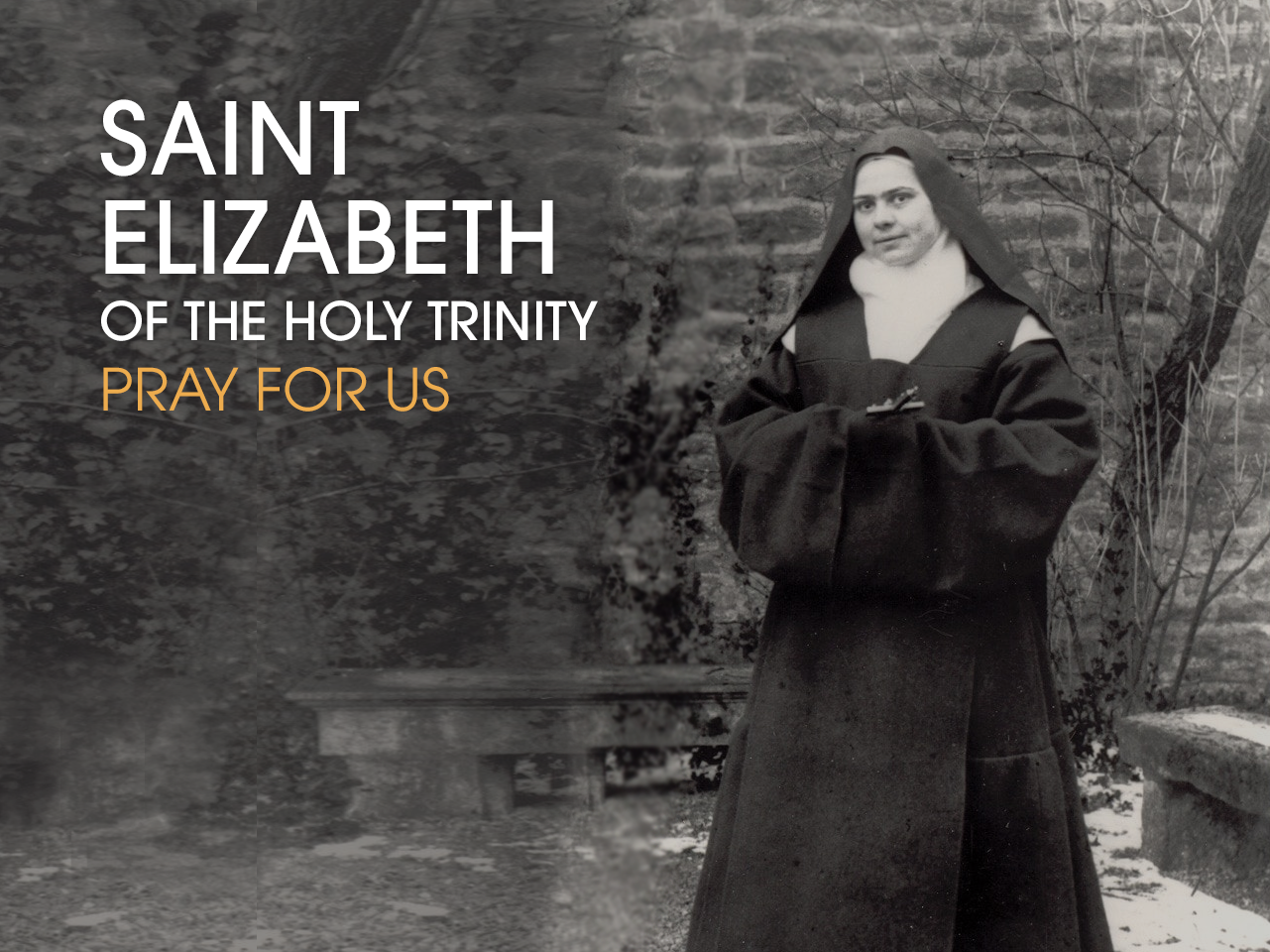

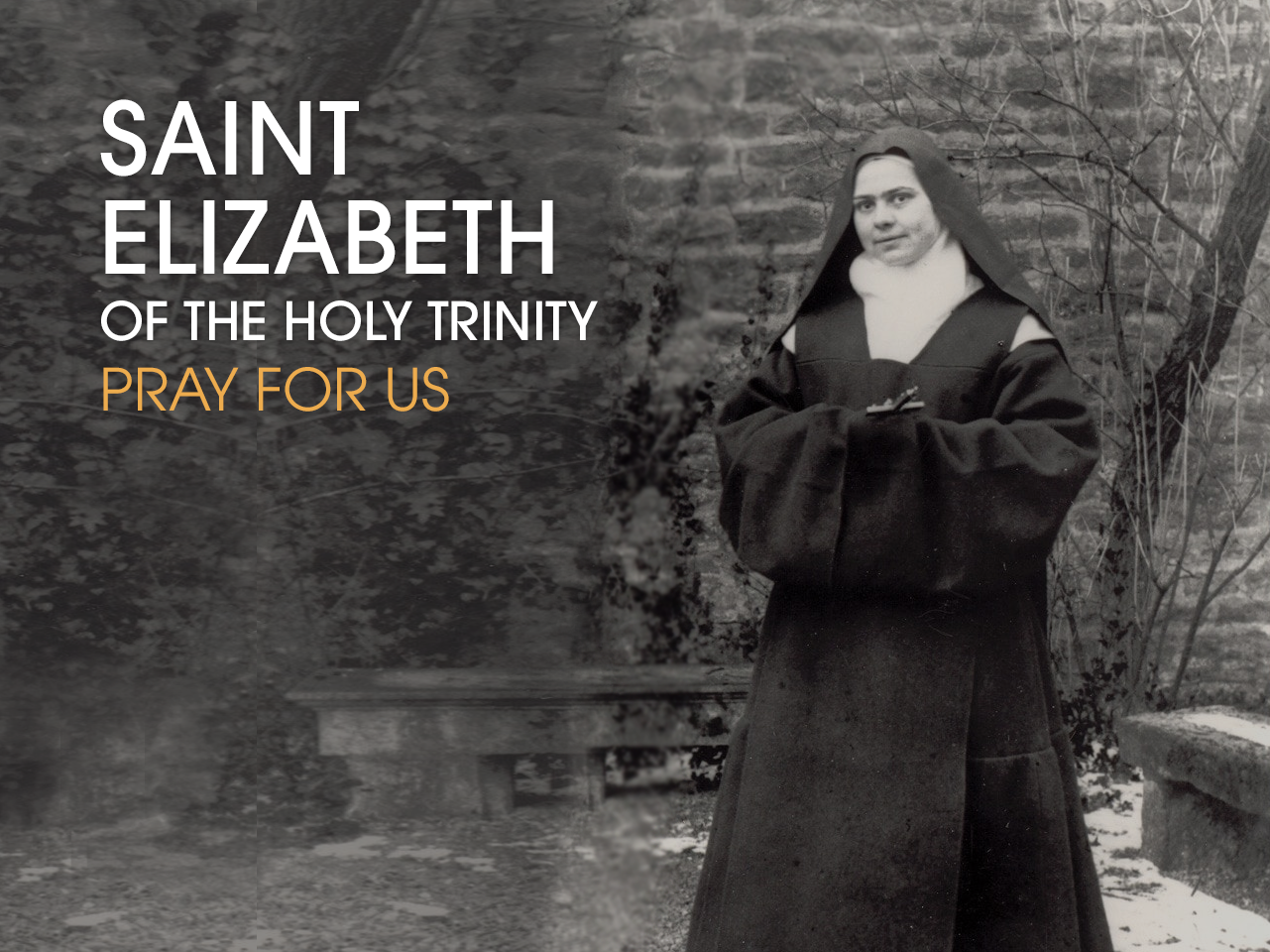

The Church celebrates St. Elizabeth of the Trinity — canonized Oct. 16, 2016 — on her feast day of Nov. 8, often election day in the US. Her spiritual mission is to help us pass through the difficulties of our time with a certain greatness of soul. Feel me?

In her own words, “We must be mindful of how God is in us in the most intimate way and go about everything with Him. Then life is never banal. Even in ordinary tasks, because you do not live for these things, you will go beyond them.”

On Nov. 9, 1906, at the age of 26, she succumbed to the final stages of Addison’s disease, an adrenal disorder which, at the time, was incurable. Her death came amid great social uncertainty for the Church and her Carmelite community in Dijon, France. Earlier that spring, the French government turned against the Church, by advancing a more aggressive secularism. The local Church was already racked with scandal, the local bishop having been removed from office by the Holy See. The state was taking legal action to confiscate Church property and put the Carmelites in exile. Anxiety over social concerns affected daily life for many — except for, perhaps, St. Elizabeth, her Carmel and those to whom she wrote.

When everything seemed to be falling down around her, St. Elizabeth of the Trinity witnessed to the power of the presence of God to establish deep peace in souls. In every lucid moment before her death, even if it was just for a moment, she did everything she could to encourage those she loved. Whether in whispered conversations or responding to letters she received, her messages were tender and filled with compassion. She managed to write a retreat for her sister, a young mother, a second retreat for her Carmelite community and numerous letters.

In the midst of their own questions and concerns, Elizabeth helped her friends discover the mysterious and transforming ways God discloses himself even surrounded by distress. As she explained, “Everything is a sacrament that gives us God.”

St. Elizabeth of the Trinity first discovered the transforming power of God’s presence through her parents and first holy Communion. Hailing from a military family and the elder of two sisters, she was born and baptized at a military camp in 1880. Afterward, the family moved to Dijon, where she grew up and entered a Carmelite monastery.

Joseph Catez, her father, a self-made decorated officer and former POW, died in 1887, when Elizabeth was still a child, but left her with a desire for heaven. Her mother, Marie Rolland, had a profound conversion before her marriage and deeply influenced her husband’s piety.

As a widow with two young girls, Marie moved to an affordable part of town, a few blocks from the parish church of Saint-Michel and across the street from the Carmel that Elizabeth would someday join. Together with her sister, Marguerite, piano, prayer and pilgrimages were important parts of Elizabeth’s upbringing. Also important were vacations with friends and family.

Young Elizabeth had a fiery temper. In a special way, her parent’s faith helped her gain a degree of self-mastery, and this was especially true at her first Communion. Witnesses testified to a profound change after Mass. The mystery of Christ’s presence drew her to prayer. In St. Elizabeth’s own words, she was no longer hungry because “God has fed me.”

Her deep prayerfulness impressed the nuns of her community even before she entered. As a teenager, she self-identified with Teresa of Avila’s descriptions of the prayer of union. She was also among the first to read an early version of Therese of Lisieux’s Story of a Soul. After reading this work, she resolved to be a Carmelite nun even over the objections of her mother. She had come to see herself as a bride of Christ.

This devotion to Christ moved her to be very involved with her parish before she entered Carmel. She catechized troubled children, first by befriending them and then by teaching them how to draw close to God in prayer. In Dijon, she is honored as much for this work as she is for her spiritual writings.

According to one of the former pastors of Saint-Michel, some of the descendants of the young people that she instructed helped to build a private school now named after her.

In her final days, Addison’s disease had emaciated Elizabeth, rendering her unable to eat or drink except for a few drops of water. Difficult thoughts sometimes tormented her as her whole body burned with pain. Yet, throughout everything, she remained devoted to Christ crucified and was completely focused on others. She promised that it would increase her joy in heaven if her friends asked for her help. She was convinced that her mission would be to help souls get out of self-occupation and enter into deep silence in order to encounter the Lord in a transformative way. To this end, she advocated faith in “the all-loving God dwelling in our souls.”

Elizabeth regarded the Trinity as the furnace of an excessive love. When her prayer evokes “My God, My Three,” she invites us to take personal possession of the Trinity. The Trinity is, for her, an interpersonal and dynamic mystery: the Father beholding the Son in the fire of the Holy Spirit. She insisted that, in silent stillness before God, the loving gaze of the Father shines within our hearts until God contemplates the likeness of His Son in the soul. Through the creative action of the Holy Spirit, the more the soul accepts the Father’s gaze of love, the more it is transformed into the likeness of the Word made flesh.

Tradition calls this loving awareness and silent surrender to the gaze of the Father mental prayer or contemplation. Elizabeth roots this in adoration and recollection and advocates its fruitfulness. Through this prayer, we gain access to our true home, the dwelling place of love for which we are created — and this is not in some future moment, but already in the present moment of time, which Elizabeth calls “eternity begun and still in progress.”

Such prayer not only sets the soul apart and makes it holy, but it glorifies the Father and even extends the saving work of Christ in the world. She called this “the praise of Glory” and understood this to be her great vocation.

By canonizing Elizabeth of the Trinity, the Church has not only validated her mission, but re-proposed the importance of silent prayer for our time. While she was not engaged in politics, St. Elizabeth was certainly concerned for her friends who were immersed in it. There is power in her prayer. Her community was never evicted or exiled, but moved years later only because it outgrew its original location. The Carmel remains a place of spiritual refreshment to this day.

Through the witness of St. Elizabeth, the Carmelites and her friends chose to allow God to establish them “immovable” in His presence. No political or cultural power deserves an absolute claim over our existence. If we call on St. Elizabeth, the Church affirms that the “Mystic of Dijon” can also help us become “the Praise of Glory,” a sign of hope for others even in the midst of social rancor.

PRAYER FOR SELF-FORGETFULNESS

“O my God, Trinity whom I adore, let me entirely forget myself, that I may abide in you, still and peaceful as if my soul were already in eternity. Let nothing disturb my peace nor separate me from you, O my unchanging God, but that each moment may take me further into the depths of your mystery! Pacify my soul! Make it your heaven, your beloved home and place of your repose. Let me never leave you there alone, but may I be ever attentive, ever alert in my faith, ever adoring and all given up to your creative action. O my beloved Christ, crucified for love, would that I might be for you a spouse of your heart! I would anoint you with glory, I would love you—even unto death! Yet I sense my frailty and ask you to adorn me with yourself. Identify my soul with all the movements of your soul, submerge me, overwhelm me, substitute yourself in me, that my life may become but a reflection of your life. Come into me as Adorer, Redeemer, and Savior. O Eternal Word, Word of my God, would that I might spend my life listening to you, would that I might be fully receptive to learn all from you. In all darkness, all loneliness, all weakness, may I ever keep my eyes fixed on you and abide under your great light. O my Beloved Star, fascinate me so that I may never be able to leave your radiance. O Consuming Fire, Spirit of Love, descend into my soul and make all in me as an incarnation of the Word, that I may be to him a super-added humanity wherein he renews his mystery. And you, O Father, bestow yourself and bend down to your little creature, seeing in her only your beloved Son in whom you are well pleased. O my “Three”, my All, my Beatitude, infinite Solitude, Immensity in whom I lose myself, I give myself to you as a prey to be consumed. Enclose yourself in me that I may be absorbed in you so as to contemplate in your light the abyss of your greatness!”

-St Elizabeth of the Trinity

“O my God, Trinity whom I adore, help me to forget myself entirely that I may be established in you as still and as peaceful as if my soul were already in eternity.

May nothing trouble my peace or make me leave You, O my Unchanging One, but may each minute carry me further into the depths of Your Mystery.

Give peace to my soul; make it Your Heaven, Your beloved dwelling and Your resting place. May I never leave You there alone but be wholly present, my faith wholly vigilant, wholly adoring, and wholly surrendered to Your creative Action.

O my beloved Christ, crucified by love, I wish to be a bride for Your Heart; I wish to cover You with glory; I wish to love You… even unto death!

But I feel my weakness, and I ask You to clothe me with Yourself, to identify my soul with all the movements of Your Soul, to overwhelm me, to possess me, to substitute Yourself for me that my life may be but a radiance of Your Life. Come into me as Adorer, as Restorer, as Savior.

O Eternal Word, Word of my God, I want to spend my life in listening to You, to become wholly teachable that I may learn all from You. Then, through all nights, all voids, all helplessness, I want to gaze on You always and remain in Your great light. O my beloved Star, so fascinate me that I may not withdraw from Your radiance.

O consuming Fire, Spirit of Love, come upon me, and create in my soul a kind of incarnation of the Word: that I may be another humanity for Him in which He can renew His whole Mystery.

And You, O Father, bend lovingly over Your poor little creature; cover her with Your shadow seeing in her only the “Beloved in whom You are well pleased.” (Mt. 17:5)

O my Three, my All, my Beatitude, infinite Solitude, Immensity in which I lose myself, I surrender myself to You as Your prey. Bury Yourself in me that I may bury myself in You until I depart to contemplate in Your light the abyss of Your greatness.

(-Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity, Prayer to the Holy Trinity).”

“May the God who is all love be your unchanging dwelling place, your cell, and your cloister in the midst of the world.” -St Elizabeth of the Trinity

“You do not possess the Sacred Humanity as you do when you receive Communion; but the Divinity, that essence the Blessed adore in Heaven, is in your soul; there is a wholly adorable intimacy when you realize that; you are never alone again!”

— Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity, around May 27, 1906 (After assuring her mother that her doctrine on the presence of God within us is not something she came up with, but rather what Scripture tells us.)

“I have found heaven on earth, since heaven is God, and God is in my soul. My mission in heaven will be to draw souls, helping them to go out of themselves to cling to God, with a spontaneous, love-filled action, and to keep them in that great interior silence which enables God to make His mark on them, to transform them into Himself.”

— Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity (Letter 122)

Love,

Matthew