-by Ken Hensley

“To wrap up this short series, I hope to describe as simply and clearly as I can the essential line thought that led me, as a Baptist minister, to embrace the Catholic teaching of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

Step One: The Witness of the Fathers

As I explained in Part I, the first step was reading the early Church Fathers and finding myself faced with descriptions of the Eucharist that were totally different than I was familiar with and that I would have ever thought to use.

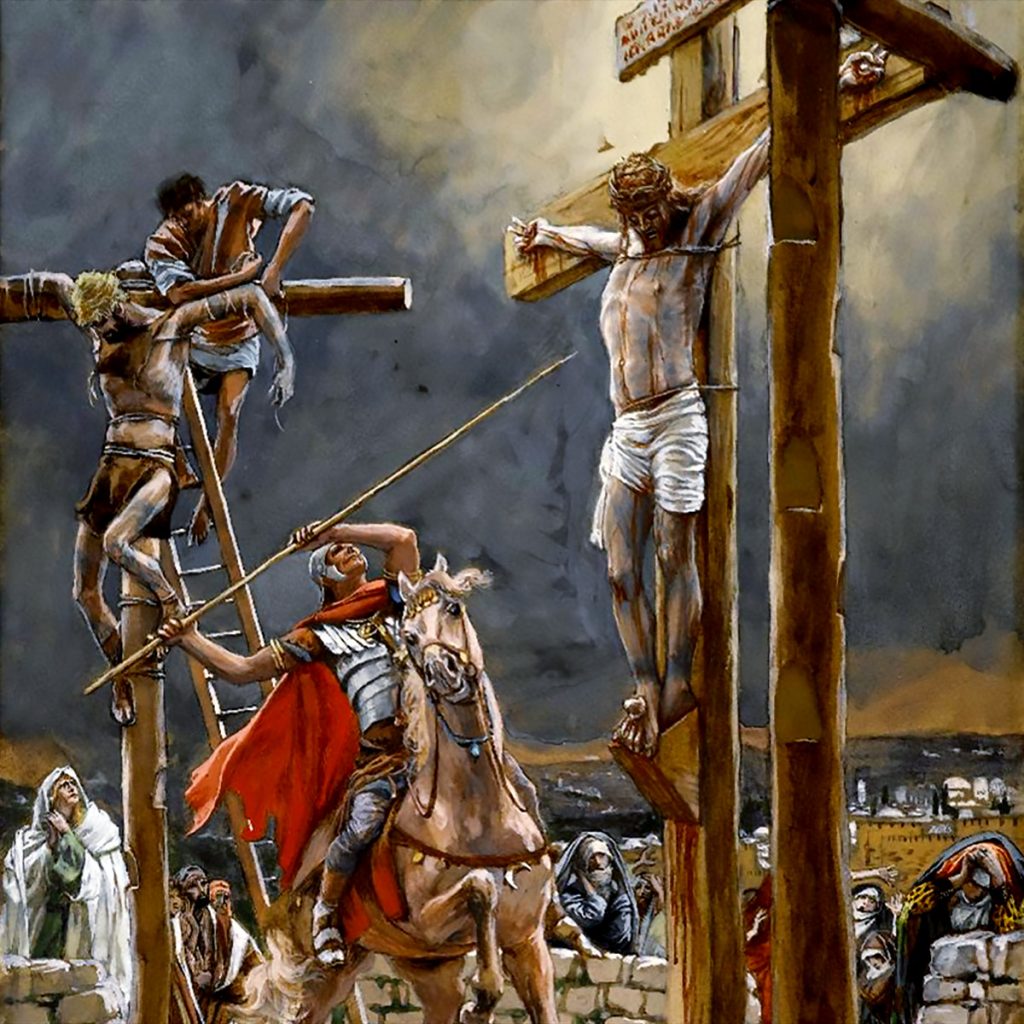

Jesus had said, “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life” (John 6:54) and the early Church seemed to take this literally.

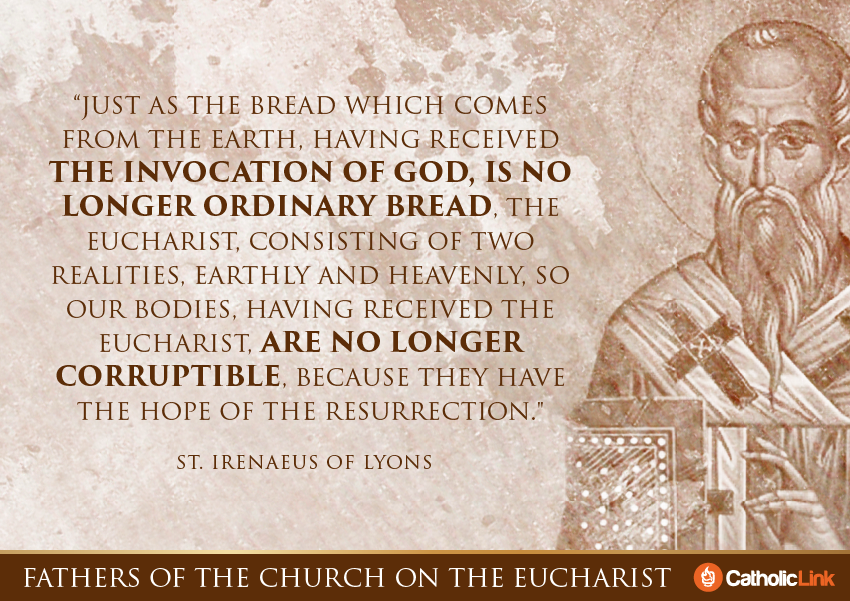

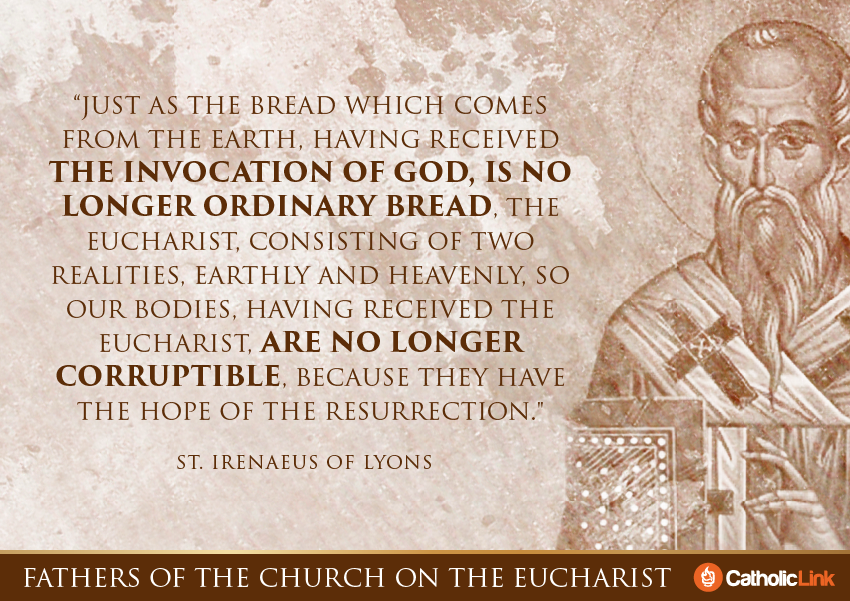

For Christians living in the earliest centuries of Christian history, the Eucharist was a meal of remembrance of Christ’s death, as I would have said as a Baptist, but it was more than that. It was supernatural food, a miraculous meal in which simple bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Christ. It was, to quote St. Ignatius of Antioch, an early bishop and disciple of St. John, the “medicine of immortality.”

The following quotation from St. Justin Martyr is fairly typical of what one finds in the writings of the early Church Fathers.

For not as common bread or common drink do we receive these; but since Jesus Christ our Savior was made incarnate by the word of God and had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so too, as we have been taught, the food that has been made into the Eucharist by the Eucharistic prayer set down by him, and by the change of which our blood and flesh is nurtured, is both the flesh and blood of that incarnated Jesus (First Apology 66).

During the past week, I’ve pulled four of five important historians of Christian doctrine off the shelf and looked again at what they have to say on this subject, only to have my own impressions confirmed.

According to one of the most prominent, J.N.D. Kelly:

Eucharistic teaching, it should be said at the outset, was in general unquestioningly realist, i.e. the consecrated bread and wine were taken to be, and were treated and designated as, the Savior’s body and blood (Early Christian Doctrines, p. 440).

Even those historians who personally reject the doctrine of Christ’s Real Presence in the Eucharist tend to admit that this indeed was the view of the Church from as far back as we can tell. Of course they take this as an illustration of how quickly the Church departed from what they perceive to be the “clear teaching” of the New Testament.

Step Two: The Examination of Scripture

The next step for me was to leave the writings of the early Church to re-examine the writings of the Apostles themselves. After all, the writings of the Fathers are not inspired. Only Scripture is inspired.

Now, I’d read the New Testament passages that touch on the Lord’s Supper many times. What I was eager to do now was read them again in the light of what I had seen in the early Church.

I wondered, would the Apostles contradict the early Church’s view of the Eucharist? Would the things they say about the Lord’s Supper support the teaching of the early Church, and possibly even be illuminated by it? Would I see things in Scripture I hadn’t noticed before?

What I found was that this was indeed the case.

First, there was nothing whatsoever in the New Testament that was not entirely consistent with the faith and teaching of the early Church, nothing that excluded or contradicted it.

But beyond this, there certain Old and New Testament biblical themes and passages that seemed positively illuminated when read in the light of the early Church’s faith and teaching (see Parts II, III and IV of this series).

I did not come away thinking I could, from the New Testament alone, somehow “prove” the doctrine of the Real Presence, or demonstrate its truth “beyond a shadow of doubt.” There simply is no passage where a “doctrine” of the Eucharist is spelled out in so many words.

But this only served to confirm something I had been coming to think for some time: that the New Testament was not written to function alone.

After all, Christian doctrine was something the Apostles taught the churches they founded, over a period of time, by word of mouth and face-to-face. St. Paul speaks, for instance, of having spent a year and six months in Corinth and three years in Ephesus teaching the believers there “the whole counsel of God” (Acts 18:11 and 20:27).

When the Apostles later wrote letters to those churches, the letters that comprise a good part of our New Testaments, with rare exceptions they were writing to those who already knew the doctrines of the faith and needed specific encouragement or correction or some issue resolved. When the churches read those letters, they read them, and understood them, in the light of what they had already been taught and already knew.

It wasn’t entirely surprising to me, then, to find that the passages in the New Testament that talk about the Lord’s Supper might need to be read and understood in the light of the early Church’s teaching.

Step Three: Relating Scripture and Tradition

All of this led to me thinking more deeply about the relationship of Scripture (the teaching of the Apostles as it was written down) to what Catholics refer to as “Tradition” (the teaching of the Apostles as it was known and preserved in the churches they founded).

As a general principle, it seemed reasonable to me to think that the teaching of the Apostles would be reflected in the faith and practice of the early Church, more than reasonable to think that when one found unanimous consent among the early Church Fathers on a particular issue, what the early Church believed would be a very good indicator of what the Apostles had taught. This made sense to me.

Given that we know all about the debates that took place in the early Church over issues both great and small (e.g. the correct day for celebrating Easter), it did not seem reasonable to me to imagine that when it came to the Eucharist, the very center of Christian worship, the Apostles would teach one thing and Church turn around and immediately teach another and there be no record of a debate on the issue.

This did not make sense.

And yet, here I was staring at quotations spread over the first three centuries of Christian history, quotations from the most prominent bishops, apologists and theologians of the Church at that time. I’m looking at quotations from every corner of the Roman Empire: from Syria (Ignatius), from Rome (Justin Martyr), from the south of France (Irenaeus), from Egypt (Clement and Origin), from Carthage and Hippo in North Africa (Tertullian and Augustine), from Milan (Ambrose).

Three centuries of witness from every corner of the Christian world supporting the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and no record of any dispute? Not even one priest or bishop rising up to say, “this is not what we received from the Apostles!”?

Having been an evangelical Protestant for many years, there was the ingrained tendency in me to think:

Listen, Ken, everything God wants us to know is recorded in the New Testament and laid out clearly enough to be understood. You need to look again at the passages, examine the exegetical arguments and decide on the basis of Scripture alone which view you think best reflects the data. That’s how these things are determined. It doesn’t really matter what the early Church thought.

At the same time, thoughts that were new to this evangelical Protestant were beginning to insinuate themselves:

But Ken, Luther examined the data and came out in one place, Calvin examined the data and came out in another. And then there were the Baptists who examined the data and hold a view of the Lord’s Supper that differs from both Luther and Calvin. What if the New Testament wasn’t meant to function “alone”?

What if the very reason sincere and prayerful students of Scripture can “examine the data” for years, decades and centuries and not agree on the nature of the Eucharist is that the writings of the Apostles need to be read and understood in the light of that teaching preserved and handed down within the Church?

Step Four: Tradition in the Early Church

The final step for me was coming to see that this is exactly the view the early Church had of the correct relationship between the inspired Scripture and the faith and teaching of the Church.

In his book Against Heresies, the first serious work of biblical theology that we possess, St. Irenaeus describes the Apostles as having deposited their teaching in the Church as a rich man deposits his money in a bank. Because of this, when there are disputes about the correct teaching, Christians, he says, can come to the Church to draw from her the truth.

As I said before, the Church, having received this preaching and this faith [from the apostles], although she is disseminated throughout the whole world, yet guarded it, as if she occupied but one house. She likewise believes these things just as if she had but one soul and one and the same heart; and harmoniously she proclaims them and teaches them and hands them down, as if she possessed but one mouth…. When, therefore, we have such proofs, it is not necessary to seek among others the truth, which is easily obtained from the Church. For the Apostles, like a rich man in a bank, deposited with her most copiously everything which pertains to the truth; and everyone whoever wishes draws from her the drink of life (Against Heresies I:10:2 and 3:4:1, c. 189 A.D.)

What can I say but that this was a way of looking at things that was beginning to make more and more sense to this Evangelical.

I had treated the New Testament as though it were a stand-alone manual of Christian doctrine. The early Christians did not think of the New Testament in this way.

I had treated the faith and practice of the early Church as though it were essentially worthless when it comes to deciding what to believe as a Christian or how to understand the New Testament. None of the early Church Fathers thought in this way. None of them.

I was beginning now to think that my understanding of the nature of both the New Testament and Tradition, and how the two should be related to one another, was simply incorrect. I was beginning to think that the Catholic Church’s view of these matters was not only more historical, but more biblical.

Sacred Scripture is the speech of God as it is put down in writing under the breath of the Holy Spirit. And sacred Tradition transmits in its entirety the Word of God, which has been entrusted to the apostles by Christ the Lord and the Holy Spirit. It transmits it to the successors of the apostles so that, enlightened by the Spirit of truth, they may faithfully preserve, expound, and spread it abroad by their preaching.

Although this sounds like another quotation from the early Church Fathers, it’s actually from Vatican Council II, Dei Verbum, the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation.”

Love & truth,

Matthew