The Spanish Civil War began in 1936. It has been described as a struggle between atheism and belief in God. One particular object of persecution was the Catholic Church. In three years, twelve bishops, 4,184 priests, 2,365 monks, and 300 nuns died for the faith. Today we celebrate eleven of those martyrs: two bishops, a diocesan priest, seven brothers of the Christian Schools, and a young laywoman. The bishops were from Almeria and Gaudix, Spain. The seven brothers of the Christian Schools were teachers at St. Joseph College in Almeria. Father Pedro Castroverde was a well-known scholar and founder of the Teresian Association. Victoria Diez Molina belonged to the Teresians. She had found a spiritual treasure in the way this group prayed and lived their Christian lives. Victoria was a teacher in a country school and was very active in her parish.

All eleven martyrs chose to die for Jesus rather than give up their Catholic faith. Brother Aurelio Maria, the director of St. Joseph College, said: “What happiness for us if we could shed our blood for the lofty ideal of Christian education. Let us double our fervor so as to become worthy of such an honor.”

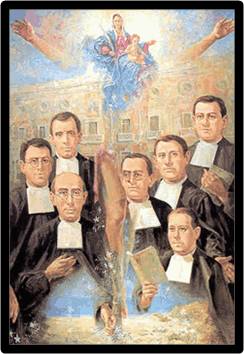

Their names are: Bishop DIEGO VENTAJA MILAN of Almeria, Bishop MANUEL MEDINA OLMOS of Guadix, Bro. AURELIO MARIA from Zafra de Zancara, Bro. JOSE CECILIO from Molina de Ubierna, Bro. EDMIGIO from Adalia, Bro. AMALIO from Salinas de Oro, Bro. VALERIO BERNARDO from Porquera de los Infantes, Bro. TEODOMIRO JOAQUIN from Puntedey and Bro. EVENCIO RICARDO from Viloria de Rioja.

The two Bishops and seven Christian Brothers died for the faith in 1936, a few weeks after the outbreak of the Civil War that ravaged Spain for almost three years. The Revolutionary Committee of Almeria decided to imprison anyone suspected of not supporting the revolution, particularly priests and religious.

On 22 July 1936, several persons came to St Joseph College and took the brothers they found there into custody. During their imprisonment they were a model for the other prisoners, encouraging them to have continual recourse to God.

On the night of 30-31 August, Brothers Edmigio, Amalio and Valerio Bernardo were executed; Brothers Teodomiro Joaquin and Evencio Ricardo on 8 September; and on the night of 12-13 September, Brothers Aurelio Maria, the director of the college, and Bro. Jose Cecilio.

The last days of Bishop Diego Ventaja Milan of Almeria and Bishop Manuel Medina of Guadix were intertwined with those of the Christian Brothers imprisoned with them. On the night of 29-30 August 1936, they were taken out to the place of execution with 15 other prisoners. Bishop Medina asked permission to speak and, according to an eyewitness, said: “We have done nothing to deserve death, but I forgive you so that the Lord will also forgive us. May our blood be the last shed in Almeria”.

These exemplary Bishops always showed pastoral concern for all their people and tirelessly traveled throughout their Dioceses to strengthen and deepen their brothers’ and sisters’ faith at a truly difficult time.

Blessed Pedro’s life was marked by simplicity and constant devotion to study. Several times he expressed a desire to live his faith to the point of sacrificing his own life. He lived the spirituality of a martyr, which served as a preparation for that fateful day when he did give his life on the morning of 28 July 1936.

Born December 3rd, 1874 at Linares, Spain and raised in a pious family, Fr Pedro felt an early call to the priesthood. He entered the seminary in Jaen in 1889, then the seminary of Guadix, Grenada. Ordained on April 17th, 1897, taught at the seminary, continued his studies, and received his licentiate in theology in Seville in 1900. He ministered in Guadix to a group of people so poor they lived in caves. He built a school for the children, and provided vocation training to the adults.

He was transferred to Madrid, and was named a canon of the Basilica of Covadonga, Asturius in 1906. His time in Guadix had impressed Pedro with the need for education for the poor. He prayed on the topic, and wrote on the need for professional training for teachers. In 1911 Pedro founded the Saint Teresa of Avila Academy, the foundation of Institución Teresiana. He joined the Apostolic Union of Secular Priests in 1912, wrote on the need for more teachers, and opened teacher training centers. He returned to teaching at the seminary at Jaen, served as spiritual director of Los Operarios Catechetical Centre, and taught religion at the Teachers Training School. In 1914 he opened Spain’s first university residence for women in Madrid. In 1921 he was transferred to Madrid and was appointed a chaplain of the Royal Palace. In 1922 he was appointed to the Central Board Against Illiteracy, and he continued to work with the Teresian Association; it received papal approval in 1924, and later spread to Chile and Italy.

In the early morning hours of the day of his execution, Bl Pedro was asked to identify himself by his captors. He cried out, “I am a priest of Christ!” He was shot by firing squad on July 28th, 1936 at Madrid, Spain.

Bishop Ventaja of Almeria had many opportunities to flee the country. He chose instead to remain with his suffering people, his suffering Church. Father Castroverde, the Teresian founder, wrote in his diary: “Lord, may I think what you want me to think. May I desire what you want me to desire. May I speak as you want me to speak. May I work as you want me to work.”

Victoria Molina was jailed on August 11, 1936. She and seventeen others were led to an abandoned mineshaft and to their death. Victoria comforted the others and said: “Come on, our reward is waiting for us.” Her last words were: “Long live Christ the King!”

Love,

Matthew