-by Nicene Guy

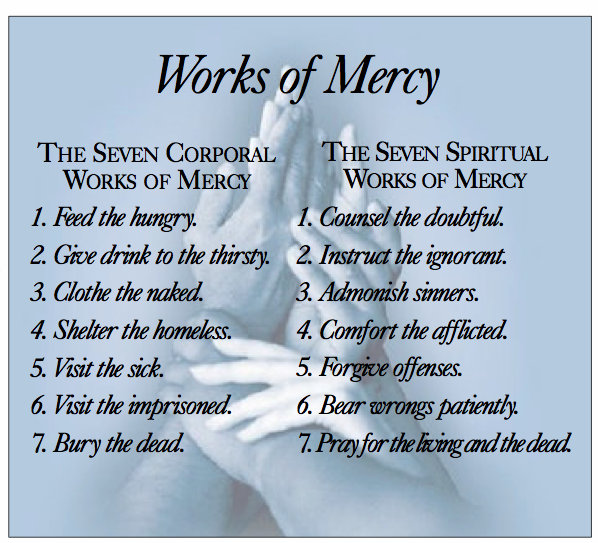

“Hunger may be among the worst forms of physical suffering by sheer magnitude, for many people go hungry. On the other hand, thirst is perhaps nearly so common, for many lack access to water. The homeless unemployed perhaps wants for food, water, shelters and at times, clothes. Nor was thirst unknown in ancient times. Much of what I said about hunger applies here, too.

Giving drink to the thirsty is an act which often is even more appreciated than feeding the hungry, in particular during the hot summer months. Those that have the space in their car (or truck, minivan, etc) could consider buying one of those 24- or 36-count packages of water bottles and stowing them on the floor of the vehicle to hand out to the homeless. These folks generally appreciate it, and it is fulfilling one (or, if you add a small snack, two) works of mercy which can literally be done as a part of a normal commute by handing out the bottles while waiting at stoplights.

In the Psalms we read that “From Thy lofty abode Thou waterest the mountains; the earth is satisfied with the fruit of Thy work” (Psalm 104:13, or Psalm 103:13 depending on numbering). Water too is a gift from God, and one which is meant for the benefit of us all. On the other hand, this verse became the subject of Saint Thomas Aquinas’ inaugural address when he became master of the sacred page (theologian) at the University of Paris. In that address, he stated that God’s watering the mountains (or hilltops) was an allegory for His pouring forth knowledge and understanding on the wise [1]. God waters the mountains, which in turn fertilized the plains and fields—God gives His knowledge and understanding and wisdom to some, who in turn share it with others who are ignorant.

“Soaking” up knowledge like a sponge, or “thirsting for knowledge,” or “drinking” in knowledge: all of these are rather natural expressions. If our spiritual hunger is for righteousness—which is opposed to sin—we might be said also to have a spiritual thirst is for knowledge and understanding and wisdom. In fact, the Beatitude actually says, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,” but righteousness means both right acts and right desires: so that we must know what to believe and what to desire and how to live to be truly righteous. Unfortunately, we are born in a “double darkness,” as Saint Thomas Aquinas notes, “of sin and ignorance.”

Thus, to instruct the ignorant is to help lift this darkness. As with counsel, a part of this instruction may take the form of discussing what is good and what is evil; what is of God and what is of the world. Good spiritual instruction therefore pertains to one (or more) of three things: what we ought to believe (creed, faith), what we ought to desire (worship, hope), and how we ought to live (morality, charity).

In my own experience, there are three things pertaining to our faith about which people are ignorant and thus in need of instruction:

There is a lot of ignorance (or confusion) about what the Church really teaches in a given doctrine or dogma, and by extension what the Church does not teach as doctrine or dogma. As Venerable Fulton Sheen once said, most people do not hate the Church (or her teachings), but rather hate what they misunderstand the Church to be (or to teach).

There is much ignorance (or, again, confusion) about what the Bible really says (and really means), in particular what Christ says an means whenever He speaks in the Gospels. We are all at times in the place of the Ethiopian eunuch of Acts, asking “How can I [understand the Scriptures], unless someone guides me?” (Acts 8:30).

There is widespread ignorance about the relationship between morality and love, between worship and hope, and between faith and the creeds. Morality is frequently treated as only “a list of do’s and don’t” rather than the demands of love. Communal worship and the liturgy are often equated with rote rituals and dead motions and empty words rather than right reverence and the nearest we get to heaven on earth. And the creed and its associated dogmas become extra distraction to hinder us from forming a relationship with Christ (like so many barnacles on a ship, as one person put it) rather than clarifications about Who God has revealed Himself to be.

Some of these things are nuanced and some contain many layers of meaning and levels of complexity. Others are more straightforward, but have been given nuances which they are not meant to contain [2]. Moreover, one cannot effectively teach what he does not know, so to instruct the ignorant requires the sacrifice of time spent in studying as well as that in teaching. And on the other hand, because knowledge of Truth comes from God, prayer is an active part of this particular work of mercy.” Amen. Amen. Amen. Prayer & Study. Study & Prayer. Holy study and prayer are work, to the glory of God.

Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of Your faithful and kindle in them the fire of Your love. Send forth Your Spirit and they shall be created. And You shall renew the face of the earth.

O, God, Who by the light of the Holy Spirit, did instruct the hearts of the faithful, grant that by the same Holy Spirit we may be truly wise and ever enjoy His consolations, Through Christ Our Lord, Amen.

—Footnotes—

[1] Knowledge, understanding, and wisdom are three gifts of the Holy Spirit. Thus, between the first two spiritual works of mercy we have also encountered four gifts of the Holy Spirit.

[2] This is common with any verse containing moral teachings, and historically also has happened to verses with theological meanings. Both still happen today, though the former is more common than the latter. More often still, they contain the straightforward literal meaning and the nuanced (metaphorical, allegorical, etc) meaning, but the latter is called upon to make the former disappear. Thus a clear and consistent proscription against sodomy becomes merely a teaching about “hospitality.” And, to be fair, attempting to sodomize a person is certainly less-than-hospitable.”

Love, and always in need of His mercy,

Matthew