(n.b. Catholics are NOT to seek martyrdom!! Marcionite heretics did this. Catholics are to embrace martyrdom if inescapable or requires apostasy to avoid.)

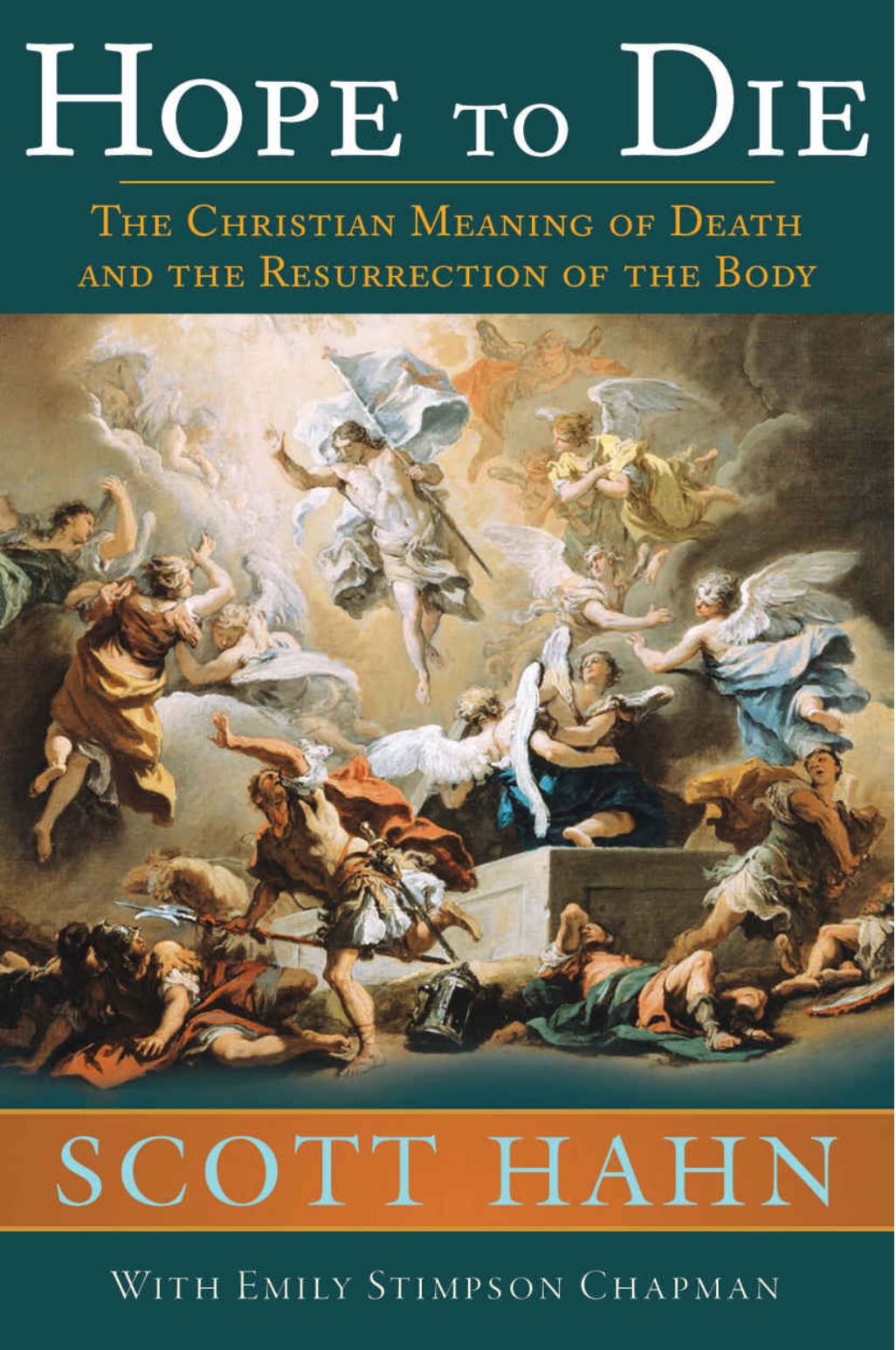

“Christianity was first preached in a world where the Greco-Roman understanding of death and the afterlife shaped much of the Western world. Across the Roman Empire, most people professed their faith in the various pagan gods, including Pluto (or Hades), who they believed ruled the Underworld. At the Underworld’s entrance, the ferryman Charon moved spirits across the River Styx from the land of the living to the land of the dead. Once they made it to the other side, all the dead faced judgment, with the good going to Elysium, the bad being thrown into the pit of Tartarus, and the mediocre rest (the majority of humanity) aimlessly drifting about in the City of Pluto (or what the Greeks called the Asphodel Meadows). Some Romans also believed those who’d been judged worthy could choose to be reincarnated.

This vision of the afterlife offered some consolation to those who actually believed it, but not enough. Most Romans, like most of humanity, still feared what awaited them in the dark room of death. And that fear manifested itself in how they treated their dead.

The pagan Romans thought that if dead bodies weren’t treated a certain way and certain conditions weren’t met, the person’s soul would be denied admittance to the Underworld. Rather than receiving its eternal reward, the soul would instead endure an almost purgatory-like existence, waiting perpetually on the wrong side of the River Styx. The Romans also believed that if they failed to provide their departed loved ones with a proper burial, those waiting ghosts would return to haunt them.

For the rich, preventing this two-headed fate was a simple matter. They paid for elaborate funerals and lengthy funeral processions, which included professional mourners and friends wearing masks designed to look like the ancestors of the deceased. They also made sure to place a coin on or in the dead person’s mouth so that the soul could pay Charon to ferry them across the River Styx.

After the funeral procession concluded, a eulogy was often given. Next, the body was placed on a pyre and burned. The remaining ashes and bones were then placed in an urn, which was interred in some kind of sepulcher—usually highly decorated, with monuments to the deceased and even lifelike pictures of them. Those sepulchers were located outside the city gates, as the Romans liked to keep their dead far from them, at a “safe” distance. They did visit the sepulcher on various days throughout the year, though, believing that by making periodic offerings to their dearly departed, what remained of the person—their “shade”—would temporarily remember who they once were and earn a brief reprieve from aimlessly wandering about the Underworld.

For the poor, funerals were less impressive, with the funerary societies they frequently joined (for a small fee) providing shorter processions (just a musician or two), no eulogy, and interment of the ashes in a humbler resting site—often catacombs carved into clay and rock outside the city.

The poorest of the poor didn’t even have that. Those with no family or friends to fear a haunting and no money to join a funerary society were simply thrown into large pits or dumped into sewers.

In the late third and fourth centuries, many of these practices among the pagan Romans began to change, with inhumation (burial) gradually replacing cremation. Although some Romans had buried their dead in previous centuries, inhumation was considered a foreign (more specifically, Jewish) practice. The growing presence of Christians in their midst, however, along with other social shifts, changed that.

For the Christians, like the Romans, how they treated the dead was bound up with what they believed about life after death. But unlike their pagan counterparts, the Christians didn’t fear death. They welcomed it. Writing in the early fourth century, St. Athanasius remarked: “Everyone is by nature afraid of death and of bodily dissolution; the marvel of marvels, is that he who is enfolded in the faith of the cross despises this natural fear and for the sake of the cross is no longer cowardly in the face of it.”1

When Jesus Christ rose from the dead, He didn’t switch a bright overhead light on in heaven, completely destroying the darkness that shrouded what awaits us after death. He gave us more of a night-light, making some things clear while leaving other things a mystery. But to Athanasius and other early Christians, that didn’t matter. The nightlight was sufficient because Jesus was there. Much like the presence of a mother or father can completely chase away a child’s fears of the dark, Jesus’s presence chased away the early Christians’ fear of death. They knew He would be there to greet them, and that was enough. Athanasius explains:

‘Before the divine sojourn of the Savior, even the holiest of men were afraid of death, and mourned the dead as those who perish. But now that the Savior has raised His body, death is no longer terrible, but all those who believe in Christ tread it underfoot as nothing, and prefer to die rather than to deny their faith in Christ, knowing full well that when they die they do not perish, but live indeed and become incorruptible through the resurrection … Even children hasten to die, and not men only, but women train themselves by bodily discipline to meet it. So weak has death become that even women, who used to be taken in by it, mock at it now as a dead thing robbed of all its strength.2‘

To those Christian men, women, and children who “hasten[ed] to die,” death wasn’t the ultimate evil or the great unknown. It was the doorway to spending eternity with their beloved: Jesus Christ. We see this conviction in the firsthand accounts of martyrs, such as Sts. Perpetua and Felicity, who faced death in Carthage’s arena in AD 203.

Both women were young wives and mothers: Felicity was pregnant at the time of their arrest, and Perpetua was still nursing her infant son. As the day of their death approached, the women didn’t want to run from it. Rather, Felicity prayed she would deliver her child soon so that she could face martyrdom with her fellow prisoners (even the Romans thought it beyond the pale to kill a pregnant women), and Perpetua gave thanks when her son finally weaned.

Felicity’s prayers were answered, and on the day of the scheduled execution, she accompanied Perpetua and their fellow Christians into the arena, “joyous and of brilliant countenances.” Perpetua sang psalms as she walked, and when the crowds demanded that the Christians be scourged before they faced the beasts, the women “rejoiced that they should have incurred any one of their Lord’s passions.” Finally, the women, like Jesus, freely gave their lives; they were not taken from them. We’re told: “when the swordsman’s hand wandered still (for he was a novice), [Perpetua] set it upon her own neck. Perchance so great a woman could not else have been slain … had she not herself so willed it.”3

In the centuries that followed, holy men and women faced death with the same eagerness that Perpetua, Felicity, and other earlier martyrs, such as St. Ignatius of Antioch, did. They wanted nothing more than to be in heaven with Christ. As Ignatius, on his way to martyrdom in AD 108, explained:

‘No earthly pleasures, no kingdoms of this world can benefit me in any way. I prefer death in Christ Jesus to power over the farthest limits of the earth. He Who died in place of us is the one object of my quest. He Who rose for our sakes is my one desire.4

One thousand years later, that same desire to be with Christ led St. Bernard of Clairvaux to describe the death of a just man not as “terrifying,” but as “consoling”:

‘His death is good, because it ends his miseries; it is better still, because he begins a new life; it is excellent, because it places him in sweet security. From this bed of mourning, whereon he leaves a precious load of virtues, he goes to take possession of the true land of the living, Jesus acknowledges him as His brother and as His friend, for he has died to the world before closing his eyes from its dazzling light. Such is the death of the saints, a death very precious in the sight of God.5‘

From the thirteenth century—when St. Rose of Viterbo advised, “Live so as not to fear death. For those who live well in the world, death is not frightening but sweet and precious”—to the nineteenth century, when St. Thérèse of Lisieux wrote: “It is not Death that will come to fetch me, it is the good God”—saint after saint encouraged Christians to welcome death. And many listened.

In Phillipe Ariès’s landmark survey of depictions of death in the literature of Western Civilization, he classifies pre-modern deaths as “tame deaths,” noting how the protagonists almost universally faced death with calm, peace, and ease. It was death, he explains, that brought people back to their senses, focused their attention, and was welcomed, almost as an old friend.6

Christians weren’t going to imitate the pagans and, as Tertullian put it, “burn up their dead with harshest inhumanity.”8 As Tertullian explained elsewhere, those who followed Christ were to “avert a cruel custom with regard to the body since, being human, it does not deserve what is inflicted upon criminals.”9 And so, from the very first, Christians buried their dead as Christ had been buried, and they did so with no fear of being made “unclean” or “polluted” by contact with the dead body. For the Christians, the dead body wasn’t “unclean” (as the Jews saw it), nor did those who handled it fear being haunted by some remnant of the person’s soul (as the pagans did). Writing in the fourth and fifth centuries, St. Augustine discussed the reverence Christians believed was due to the dead body, noting: The bodies of the dead, and especially of the just and faithful are not to be despised or cast aside. The soul has used them as organs and vessels of all good work in a holy manner. … Bodies are not ornament or for aid, as something that is applied externally, but pertain to the very nature of the man.10

Importantly, Christians understood the injunction to care for and bury the dead as universal; it applied to all bodies—the bodies of the poor, the stranger, the diseased, even the pagan. Accounts about early Christian communities are filled with stories of them seeking out the forgotten poor and burying them with the same care they showed to family members. Tertullian also tells us that in his native Carthage and other cities, the Church’s common resources were used to pay for the burying of the dead. There was no throwing the bodies of the poor into a pit or the sewers among the Christians.

Their pagan neighbors took note of that. In his essay “To Bury or Burn?,” the Protestant ethicist David W. Jones tells us:

‘The last of the non-Christian emperors, Julian the Apostate (AD 332–363), identified “care of the dead” as one of the factors that contributed to the spread of Christianity throughout the Roman world. The church historian Philip Schaff, too, identified Christians’ display of “decency to the human body” in showing care for the dead as one of the main reasons for the church’s rapid conquest of the ancient world.11‘

In time, burying the dead would become known as one of the seven corporal works of mercy, considered as much an act of charity as feeding the hungry or tending to the sick. Religious associations, such as the Archconfraternity of the Beheaded John the Baptist in Florence and the Archconfraternity of St. Mary of the Oration and Death in Rome, also were formed to offer Christian funerals and burials to those who would otherwise have none.

No bodies, though, not rich nor poor, received as much attention as those of the martyrs.”

Love & Resurrection,

Matthew

1 Athanasius, On the Incarnation, 58.

2 Athanasius, On the Incarnation, 57.

3 Tertullian, The Passion of the Holy Martyrs Perpetua and Felicity, 6.

4 Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Romans, 6.

5 Bernard of Clairvaux, quoted in Charles Kenny, Half Hours with the Saints and Servants of God (London: Burns and Oats, 1882), 450.

6 See Phillipe Ariès, Western Attitudes Toward Death, trans. Patricia Ranum (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975), 1–25.

8 Tertullian, On the Resurrection of the Flesh, 1.

9 Tertullian, A Treatise on the Soul, 51.

10 Augustine, On the Care of the Dead, 5.

11 Jones, “To Bury or Burn?,” 337.