-Saint Catherine of Genoa adoring the Crucified Christ, by Giovanni Agostino Ratti

I LOVE MARRIED SAINTS!!!!! DID I MENTION I LOVE MARRIED SAINTS????!!!! It is NOT any oxymoron, but rather our Christian duty and our obligation due to Almighty God & our spouse.

Born an aristocrat in Genoa in 1447 in the Vico del Filo and baptized as Caterina Fieschi, the youngest of five children, Catherine’s parents were Jacopo Fieschi and Francesca di Negro. Catherine’s family had papal connections. She was related to Pope Innocent V and Pope Adrian V, and Jacopo became Viceroy of Naples. When Catherine was born, many Italian nobles were supporting Renaissance artists and writers. The needs of the poor and the sick were often overshadowed by a hunger for luxury and self-indulgence.

She was known to be pious and prayerful even as a young girl. “Taller than most women, her head well proportioned, her face rather long but singularly beautiful and well shaped, her complexion fair and in the flower of her youth rubicund, her nose long rather than short, her eyes dark and her forehead high and broad; every part of her body was well formed”, Catherine wished to enter a convent when about thirteen, perhaps inspired by her sister, Limbania, who was an Augustinian nun, but the nuns to whom her confessor applied refused her on account of her youth, after which she appears to have put the idea aside without any further attempt.

Her father, Jacopo, passed away shortly after this. Her eldest brother, Giacomo inherited everything. He wishing to resolve differences with the Adorno family, another noble family with whom the Fieschi’s were at odds, and so concocted the idea of marrying Catherine to the Adorno boy, Giuliano, who had returned to Genoa to marry after various military and trading experiences in the Middle East.

Giacomo obtained his mother’s support and found Giuliano more than willing to accept the beautiful, noble and rich bride proposed to him; as for Catherine herself, she would not refuse this cross laid on her at the command of her mother and eldest brother. On 13 January, 1463, at sixteen, Catherine was married to the young Genoese nobleman, Giuliano Adorno. Giuliano was described by a witness of the time to be possessed of a “strange and recalcitrant nature” who wasted his substance on disorderly living including gambling.

The childless marriage turned out wretchedly; Giuliano proved faithless, violent-tempered, and a spendthrift, who made the life of his wife a misery. He was careless and unsuccessful as a husband and provider, often cruel, violent and unfaithful, and reduced them to bankruptcy. Catherine became indifferent to her faith, and fell into a depression.

Details are scanty, but it seems at least clear that Catherine spent the first five years of her marriage in silent, melancholy submission to her husband; and that she then, for another five, turned a little to the world for consolation in her troubles. She tried to find serenity in the distractions of the world. As always, it didn’t work.

Catherine, living with Giacomo in his fine house in the Piazza Sant’ Agnete, at first entirely refused to adopt his worldly ways, and lived “like a hermit”, never going out except to hear Mass. But when she had thus spent five years, she yielded to the remonstrances of her family, and for the next five years practiced a certain commerce with the world, partaking of the pleasures customary among the women of her class but never falling into sin. Increasingly she was irked and wearied by her husband’s lack of spiritual sympathy with her, and by the distractions which kept her from God. Then, ten years after her marriage, she prayed “that for three months He (God) may keep me (Catherine) sick in bed” so that she might escape her marriage, but her prayer went unanswered.

Catherine became so despondent with a profound sense of emptiness and bitterness, she went to talk to her sister, Limbania, at the convent to unload her woes. After listening, Limbania insisted Catherine return the following day and make her confession to the confessor of the nuns at the convent. On 22 March 1473, while making this confession, Catherine was struck down by a vision, the revelation of God’s love and her own sinfulness, and fell into a religious ecstasy; her interior state, and her contact with the Truth she had received in the vision, stayed with her the rest of her life.Suddenly, as she was kneeling down at the confessional, Catherine explained “my heart was wounded by a dart of God’s immense love, and I had a clear vision of my own wretchedness and faults and the Most High Goodness of God. She fell to the ground, all but swooning/fainting”, of this experience she later wrote her heart cried out, “no longer the world, no longer sin”. The confessor was at this moment called away, and when he came back she could speak again, and asked and obtained his leave to postpone her confession. After this revelation occurred she abruptly left the church, without finishing her confession. This marked the beginning of her life of close union with God in prayer.

She hurried home, to shut herself up in the most secluded room in the house, weeping, and for several days she stayed there absorbed by consciousness of her own wretchedness and of God’s mercy in warning her. She had a vision of Our Lord, weighed down by His Cross and covered with blood, and she cried aloud, “O Lord, I will never sin again; if need be, I will make public confession of my sins.” It was an experience she found difficult/nearly impossible to describe. “Oh, Love! Can it be that You have called me with so much love, and revealed to me at one view, what no tongue can describe?…I have no longer either soul or heart; but my soul and my heart are those of my Beloved…”.

She now entered on a life of prayer and penance. She obtained from her husband a promise, which he kept, to live with her as a brother. She made strict rules for herself–to avert her eyes from sights of the world, to speak no useless words, to eat only what was necessary for life, to sleep as little as possible and on a bed in which she put briars and thistles, to wear a rough hair shirt. Every day she spent six hours in prayer. She rigorously mortified her affections and will.

Soon, guided by the Ladies of Mercy, she was devoting herself to the care of the sick poor. In her plain dress she would go through the streets and byways of Genoa, looking for poor people who were ill, and when she found them she tended them and washed and mended their filthy rags. Often she visited the hospital of St. Lazarus, which harbored incurables so diseased as to be horrible to the sight and smell, many of them embittered. In Catherine they aroused not disgust but charity and love; she met their insults with unfailing gentleness.

From the time of her conversion she hungered insatiably for the Holy Eucharist, and the priests admitted her to the privilege, very rare in that period, of daily communion. Once upon receiving Communion, Catherine gazed towards her Lord and said, “O Lord, perhaps Thou wouldst draw me to Thee by this fragrance? I do not desire it; I desire nothing but Thee, and Thee wholly; Thou knowest, that from the beginning, I have asked of Thee the grace that I might never see visions, nor receive external consolations, for so clearly do I perceive Thy goodness, that I do not seem to walk by faith but by a true and heartfelt experience.”

For twenty-three years, beginning in the third year after her conversion, she fasted completely throughout Lent and Advent, except that at long intervals she drank a glass of water mixed with salt and vinegar to remind herself of the drink offered to Our Lord on the cross, and during these fasts she enjoyed exceptional health and vigor. For twenty-five years after her conversion she had no spiritual director except Our Lord Himself. Then, when she had fallen into the illness which afflicted the last ten years of her life, she felt the need for human help, and a priest named Fr. Cattaneo Marabotto, who had a position of authority in the hospital in which she was then working, became her confessor. To him she explained her states, past and present, and he compiled the “Memoirs”.

The time came when the directors of the great hospital in Genoa asked Catherine to superintend the care of the sick in this institution. She accepted, and hired near the hospital a poor house in which she and her husband lived out the rest of their days. Her prayers were still long and regular and her raptures frequent, but she so arranged that neither her devotions nor her ecstasies interfered with her care of the sick. Although she was humbly submissive even to the hospital servants, the directors saw the value of her work and appointed her rector of the hospital with unlimited powers.In 1497 she nursed her husband through his last illness. In his will he extolled her virtues and left her all his possessions. After Giuliano’s death, her life was devoted to her relationship with God, through “interior inspiration” alone. She used no other and needed no other forms of prayer.

When Catherine was fifty-three, she fell ill. Worn out by her life of ecstasies, her burning love for God, labor for her fellow creatures and her privations; during her last ten years on earth she suffered much. She died in 1510, worn out with labors of body and soul. Her death had been slow with many days of pain and suffering as she experienced visions and wavered between life and death.

In 1551, 41 years after her death, a book about her life and teaching was published, entitled “Libro de la vita mirabile et dottrina santa de la Beata Caterinetta de Genoa”. This is the source of her “Dialogues on the Soul and the Body” and her “Treatise on Purgatory”. It is her writings that have continued her fame today; during her canonization inquiry, the Holy Office announced that her writings alone were enough to prove her sanctity. Her writings also became sources of inspiration for other religious leaders such as Saints Robert Bellarmine and Francis de Sales and Cardinal Henry Edward Manning.

Catherine wrote about purgatory which, she said, begins on earth for souls open to God. Life with God in heaven is a continuation and perfection of the life with God begun on earth. For Catherine, purgatory was not another physical place to go to atone for one’s sins, but rather, an interior cleansing. She speaks of the soul’s purification onto complete union with God. “The soul”, Catherine says, “presents itself to God still bound to the desires and suffering that derive from sin and this makes it impossible for it to enjoy the beatific vision of God”. Catherine asserts that God is so pure and holy that a soul stained by sin cannot behold/be in the beatific vision, the presence of the Divine Majesty. The soul is aware of the immense love and perfect justice of God and consequently suffers for having failed to respond in a correct and perfect way to this love; and love for God itself becomes a flame, love itself cleanses the soul from the residue of sin. In writing about purgatory, Catherine reminds us of a fundamental truth of faith that becomes for us an invitation to pray for the deceased so that they may attain the beatific vision of God in the Communion of Saints (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 1032).

St Catherine of Genoa is patroness of Brides, Childless People, Difficult Marriages, People Ridiculed For Their Piety, Victims Of Adultery, and Widows, among other causes.

“We should not wish for anything but what comes to us from moment to moment, exercising ourselves none the less for good. For he who would not thus exercise himself, and await what God sends, would tempt God. When we have done what good we can, let us accept all that happens to us by Our Lord’s ordinance, and let us unite ourselves to it by our will. Who tastes what it is to rest in union with God will seem to himself to have won to Paradise even in this life.” -St Catherine of Genoa

“It remains for us to pray the Lord, of His great goodness and by the intercession of this glorious Seraphim, to give us His love abundantly, that we may not cease to grow in virtue, and may at last win to eternal beatitude with God who lives and reigns for ever and ever.” –St Catherine of Genoa

“Since I began to love, love has never forsaken me. It has ever grown to its own fullness within my innermost heart.” –St Catherine of Genoa

“If it were possible for me to suffer as much as all the martyrs have suffered, and even Hell itself, for the love of God, and in order to make satisfaction to Him, it would be after all only a sort of injury to God, in comparison with the love and goodness with which He has created, and redeemed, and, in a special manner, called me. For man, unassisted by God’s grace, is even worse than the devil, because the devil is a spirit without a body, while man, without the grace of God, is a devil incarnate. Man has a free will, which, according to the ordination of God, is in nowise bound, so that he can do all the evil that he wills; to the devil, this is impossible, since he can act only by the divine permission; and when man surrenders to him his evil will, the devil employs it, as the instrument of his temptation.”-St Catherine of Genoa

“The souls in Purgatory see all things, not in themselves, nor by themselves, but as they are in God, on whom they are more intent than on their own sufferings. . . . For the least vision they have of God overbalances all woes and all joys that can be conceived. Yet their joy in God does by no means abate their pain. . . . This process of purification to which I see the souls in Purgatory, subjected, I feel within myself.” -St Catherine of Genoa“I see that whatever is good in myself, in any other creature, or in the saints, is truly from God; if, on the other hand, I do any thing evil, it is I alone who do it, nor can I charge the blame of it upon the devil or upon any other creature; it is purely the work of my own will, inclination, pride, selfishness, sensuality, and other evil dispositions, without the help of God I should never do any good thing. So sure am I of this, that if all the angels of heaven were to tell me I have something good in me, I should not believe them. So long as any one can speak of divine things, enjoy and understand them, remember and desire them, he has not yet arrived in port; yet there are ways and means to guide him thither. But the creature can know nothing but what God gives him to know from day to day, nor can he comprehend beyond this, and at each instant remains satisfied with what he receives. If the creature knew the height to which God is prepared to raise him in this life, he would never rest, but on the contrary would feel a certain craving, a vehement desire to reach quickly that ultimate perfection, and would think himself in Hell until he had obtained it.”-St Catherine of Genoa

“If it were given to a man to see virtue’s reward in the next world, he would occupy his intellect, memory and will in nothing but good works, careless of danger or fatigue.” – St Catherine of Genoa

“We must not wish anything other than what happens from moment to moment, all the while, however, exercising ourselves in goodness. And to refuse to exercise oneself in goodness, and to insist upon simply awaiting what God might send, would be simply to tempt God.”

–St. Catherine of Genoa

“I see clearly with the interior eye, that the sweet God loves with a pure love the creature that He has created, and has a hatred for nothing but sin, which is more opposed to Him than can be thought or imagined.”

–St. Catherine of Genoa

“The fullness of joy is to behold God in everything.” -St. Catherine of Genoa

“The greatest suffering of the souls in purgatory, it seems to me, is the awareness that something in them displeases God, that they have deliberately gone against His great goodness. I can also see that the divine essence is so pure and light-filled—much more than we can imagine—that the soul that has but the slightest imperfection would rather throw itself into a thousand hells than appear thus before the divine presence.”

—St. Catherine of Genoa

Shortly before her death Catherine told her goddaughter: “Tomasina! Jesus in your heart! Eternity in your mind! The will of God in all your actions! But above all, love, God’s love, entire love!”

“Through the words of this great Saint and the Gift that God had Graced her, we have gained a better understanding of the graphic damage that sin can do to a soul and also how the soul can be restored back to God’s Loving embrace through participation of the Sacraments. We also understand how God can transform a soul to be a divine reflection of Himself when the soul surrenders itself to the Triune Spirit. And through the works of Saint Catherine we also understand Purgatory and the Holy Souls who wait to be released into Heaven by our prayers and penances and when we offer up a Mass for the repose of their soul as these Holy souls endure the purgation of Purgatory, as they thirst to be re-united with God in Heaven. May we reflect deeply on the messages of Saint Catherine of Genoa and how God illuminated her soul so as to instruct the faithful.” – a commentator on St Catherine of Genoa

“The purifying fires draw them ever upward and closer to God.”

—Catherine of Genoa

Love,

Matthew

Sep 18 – St Joseph of Cupertino, (1603-1663), The Flying Friar

The Flying Nun you’ve probably heard of. (Sally Field/Sister Bertrille, ora pro nobis!) And, school has begun. And, school is hard these days. There is more to learn than ever and more than ever riding on success. Even adults have to go back to school these days to remain competitive.

That is not intended to pressure students any more than they already pressure themselves, the successful ones and even the ones that try as hard as they can but are not as successful. Students lack adult perspective, by definition. Unless successful at or preferably beyond their and their guardians’ expectations, they do not understand yet/have the maturity to embrace failure as a means of personal growth and realize its value, and even be thankful for it/rejoice in it for the new perspectives it brings and the death of the old way of seeing and thinking. It brings in life sweet revelations and humility. I, obviously, require MUCH more! 🙂 Deo gratias!

The young need our support and encouragement always. It’s tough out there for the young. They are not permitted the joy and luxury, to which all young persons should be, of being young very long these days. What a shame for them and for us. The young refresh us. Take us back to happier days of simpler moments in our lives/redeem us; most of us. (cf Mt 18:3)

Although, not regular supplicants, the most unspiritual student, even non-Catholics, have been known to offer the occasional prayer during examination or other stressful scholarly moment to St Thomas Aquinas, or in this case, St Joseph of Cupertino. Couldn’t hurt, right? 🙂

Joseph, as a child, was noticed to be remarkably unclever, dull, dimwitted. We might consider him today mentally disabled. But, God writes straight with crooked lines (~ancient Portugese proverb).

Born Giuseppe Maria Desa in Cupertino, Apulia, June 17, 1603, Joseph’s father, Felice Desa, was a poor carpenter in the fortified town of Cupertino, located in the heel of the boot of Italy, on the Apulian peninsula within the then Kingdom of Naples. He died before the boy was born.

Known locally as a charitable man, Felice often guaranteed the debts of his poorer neighbors, often driving himself into debt as a result. Felice died prior to Joseph’s birth, leaving his wife Francesca Panara destitute and pregnant with the future saint.

Creditors drove his mother, Francesca, from her home, sold to pay Felice’s debts. Because of this, Joseph was born in the stable behind their home. (Sound familiar? Now WHERE have I heard that before? Think. Think. Think. Nope. Nothing.)

Starting at age eight, he became prone to ecstatic visions that left him gaping and staring into space. His childhood detractors gave him the pejorative nickname, “the Gaper.” He had a hot temper, which his strict mother worked to overcome. Francesca became hardened by her circumstances, and everything became Joseph’s fault.

Joseph knew he was not as quick as the others, or athletic, or comely. Other children were praised. Joseph was not. Other children were given presents or nice clothes. Joseph was not. Absent-minded, awkward, nervous, sudden noises such as the ringing of a church bell would cause Joseph to drop all his books on the floor. He even had trouble making friends. He couldn’t carry on a conversation or tell a story. His very sentences would stop in the middle because he could not find the right words, no matter how he tried. Joseph was something of a trial, to even those who tried to love him. Nobody wanted Joseph. He learned this early on. He began to think of himself as a dumb mule, a jackass. When called to account, his only response would be, “I forgot.”

Apprenticed to a shoemaker, Joseph made a very poor cobbler, but he kept trying. At age 17 Joseph applied for admittance to the Friars Minor Conventuals, but was refused due to his lack of education. He applied to the Capuchins, was accepted as a lay-brother in 1620, but his ecstasies made him unsuitable for work. Often he was taken in ecstasy and, oblivious of what he was doing, he would drop the food or break the dishes and trays. As a penance, bits of broken plates were fastened to his habit as a humiliation and reminder not to do the same again. Eventually, he was dismissed. His habit taken from him, he was told to go. It was the hardest day of his life. When they took his habit, it was like their taking his skin from him, he said. Now what was he going to do? Could he do? Joseph was despondent.

That was not the end of his troubles. When he had recovered from his stupor on the road outside the friary, he found he had lost some of his lay clothes. He was without a hat; he had no boots or stockings, his coat was moth-eaten and worn. Such a sorry sight did he appear, that as he passed a stable down the lane some dogs rushed out on him, and tore what remained of his rags to still worse tatters.

Having escaped from the dogs, poor Joseph trudged along, wondering what next would happen. He passed some shepherds tending sheep. They took him for a dangerous character. When questioned he could give no account of himself and they were about to give him a beating; fortunately one of them had a little pity, and persuaded them to let him go free. But it was only to pass from one trouble into another. Scarcely had he gone a little further down the road when a nobleman on horseback met him. The latter could see in Joseph nothing but a suspicious tramp who had no business in those parts, and thought to hand him over to the police; only when, after examining him, he had come to the conclusion that Joseph was too stupid to be harmful did he let him go.

At last, torn and battered and hungry, Joseph came to a village where one of his uncles lived. He was a prosperous tradesman there, with a thriving little shop of his own; and Joseph hoped he would find with him some kind of comfort, perhaps another start in life. But he was sadly disappointed.

Nephews of Joseph’s type, even at their best, are not always welcome to prosperous uncles, much less when they turn up unexpectedly, with scarcely a rag on their backs. Joseph’s uncle was no better and no worse than others. He looked at the poor lad who stood before him, soiling his clean shop floor with his dirty, bare feet, disgracing himself and his house with his rags, and he was just a little ashamed to own him as a nephew.

Evidently, he said to himself, the boy had inherited his father’s improvident ways, and would come to nothing good. He was already well on the road to ruin; to help him would only make him worse. Besides, Joseph’s father already owed him money; how, then, could he be expected to do anything for the son?

So instead of offering him assistance, Joseph’s uncle turned upon him; blamed him for his sorry plight, which, he said, he must have brought upon himself; railed at him because of his father’s debts, which such a son could only increase; finally pushed him into the street, without a coin to help him on his way. There was nothing to be done; he must move on; nobody wanted Joseph.

At last he reached his native town, and made for his mother’s cottage. During Joseph’s absence, things had gone no better than before. He came to the door in fear and trembling, remembering well how his mother had long since tired of his presence. Still he would venture; it was the only place left where he might hope for a shelter and he must try. He opened the door and looked in; inside he found his mother, busy about her little hovel. Weary and footsore, hungry and miserable, no longer able to stand, he fell on the floor at his mother’s feet; he could not speak a word, though his glistening eyes as he looked up at her were eloquent.

But they failed to soften his mother. She had gone through hard times enough and was unprepared for more. What? Had he come back to burden them, now when things were worse than ever? And further disgraced, besides, for had he not been expelled from a monastery? How the neighbors would talk, and scorn the mother for having such a son; an unfrocked friar, a ne’er-do- well, a common tramp, and that at an age when other youths were earning an honest livelihood! She could restrain herself no longer. As he lay at her feet she rounded on him.

“You have been expelled from a house of religious,” she cried. “You have brought shame upon us all. You are good for nothing. We have nothing for you here. Go away; go to prison, go to sea, go anywhere; if you stay here there is nothing for you but to starve.”

But she was not content with only words. She had a brother who was a Franciscan, holding some sort of office. In high dudgeon, she went off to him, and gave him a piece of her mind about the way his Order had dismissed her son, and put him again on her hands. She appealed to him to have him taken back, in any capacity they liked; so long as she was rid of him, they could do with him what they chose. But as for readmission, the good Franciscans were immovable. Joseph had been examined before, and had been declared unsuitable; he had been tried, and had been found wanting; the most they could do was to give him the habit of the Third Order, and employ him somewhere as a servant. He was appointed to the stable; there he could do little harm. Joseph was made the keeper of the monastery mule.

And then a change came. Joseph set about his task since it was now clear that he could never be a Franciscan, at least he could be their servant. He said not a word in complaint; what had he to complain of? He told himself that all this was only what he might have expected; being what he was, he might consider himself fortunate to find any job at all entrusted to him. He asked for no relief; he took the clothes and the food they chose to give him; he slept on a plank in the stable, it was good enough for him. What was more, in spite of his dullness, perhaps because of it, Joseph had by nature a merry heart. However great his troubles, the moment a gleam of sunshine shone upon him he would be merry and laugh. The troubles were only his desert and were to be expected; when brighter times came he enjoyed them as one who had received a consolation wholly unlooked for, and wholly undeserved.

Gradually this became noticed. Friars would go down to the stable for one reason or another, and always Joseph was there to welcome them, apparently as happy as a lord. It was seen how little he thought of himself, how glad he was to serve; since he could not be a begging friar, sometimes in his free moments he went out and begged for them on his own account. His lightheartedness was contagious; his kindly tongue made men trust him; it was noticed how he was welcomed among the poorest of the poor, who saw better than others the man behind all his oddities. He might make a Franciscan after all. The matter was discussed in the community chapter; his case was sent up to a provincial council for favorable consideration; it was decided, not without some qualms, to give him yet another trial.

In this way Joseph was once more admitted to the Order, but what was to be done with him then? His superiors set him to his studies, in the hope that he might learn enough to be ordained, but the effort seemed hopeless. With all his good intentions he learnt to read with the greatest difficulty, and, says his biographer, his writing was worse. He could never expound a Sunday Gospel in a way to satisfy his professors; one only text seemed to take hold of him, and on that he could always be eloquent; speaking from knowledge which was not found in books. It was a text of St. Luke (xi, 27): “Beatus venter qui Te portavit.”

Minor Orders in those days were easily conferred, and even the subdiaconate; but for the diaconate and the priesthood a special examination had to be passed, in presence of the bishop himself. As a matter of form, but with no hope of success, Joseph was sent up to meet his fate. The bishop opened the New Testament at haphazard; his eye fell upon the text “Beatus venter qui Te portavit,” and he asked Joseph to discourse upon it. To the surprise of everyone present Joseph began, and it seemed as if he would never end; he might have been a Master in Theology lost in a favorite theme. There could be no question about his being given the diaconate.

When it was a question of the priesthood, the first candidates did so well that the remainder of the candidates, Joseph among them, were passed without examination and Joseph was ordained a priest in 1628. Deo gratias!

His virtues were such that he became a cleric at 22, a priest at 25, on March 4, 1628. Joseph still had little education, could barely read or write, but received such a gift of spiritual knowledge and discernment that he could solve intricate questions. During this period of his life, the spiritual consolations he had enjoyed since his childhood abandoned him. Later he wrote to a friend about that difficult time: “I complained a lot to God about God. I had left everything for Him, and He, instead of consoling me, delivered me to mortal anguish.”

He continued: “One day, when I was weeping and wailing in my cell, a religious knocked on my door. I did not answer, but he entered my room and said: ‘Friar Joseph, how are you?’

“‘I am here to serve you,’ I answered.

“‘I thought you did not have a habit,’ he continued.

“‘Yes, I have one, but it is falling apart,’ I responded.

“Then, the unknown religious gave me a habit, and when I put it on, all my despair disappeared immediately. No one ever knew who that religious was.”

There were many, by this time, besides the very poor who had come to realize the wonderful simplicity and selflessness of Joseph, hidden beneath his dullness and odd ways; a few had discovered the secret of his abstractedness, when he would lose himself in the labyrinth of God.

Nevertheless he remained a trial, especially to the practical-minded; to the end of his life he had to endure from them many a scolding. Often enough he would go out begging for the brethren, and would come home with his sack full, but without a sandal, or his girdle, or his rosary, or sometimes parts of his habit. His friends among the poor had taken them for keepsakes, and Joseph had been utterly unaware that they had gone. He was told that the convent could not afford to give him new clothes every day. “Oh! Father,” was his answer, “then don’t let me go out any more; never let me go out any more. Leave me alone in my cell to vegetate; it is all I can do.”

For indeed, as we have seen, Joseph had no delusions about himself; and his ordination did not make him think differently. True he was a priest, but everybody knew how he had received the priesthood. He could assume no airs on that account.

On the contrary, knowing what he was, he could only act accordingly. In spite of his priestly office, Joseph could only live the life he had lived before. He would slip down to the kitchen and wash up the dishes; he would sweep the corridors and dormitories; he would look out for the dirtiest work that others shirked, and would do it; when building was going on in the convent he would carry up the stones and mortar; if anyone protested, declaring that such work did not become a priest, Joseph would only reply to them: “What else can Brother Ass do?”, a name given him by his brothers in religion.

But now began that wonderful experience the like of which is scarcely to be paralleled in the life of any other saint. It was first in his prayer. Joseph’s absent-mindedness, from his childhood upwards, had not been only a natural weakness, it was due, in great part, to a wonderful gift of seeing God and the supernatural in everything about him, and he would become lost in the wonder of it all. Now when he was a friar, and a priest besides, the vision grew stronger; it seemed easier for him to see God indwelling in His creation than the material creation in which he dwelt. The realization became to him so vivid, so engrossing, that he would spend whole days lost in its fascination, and only an order from his superiors could bring him back to earth.

Joseph’s visions and ecstasies would come suddenly upon him anywhere; as it were from out of space the eyes of God would look at him, or on the face of nature the hand of God would be seen at work, disposing all things.

Joseph would stand still, exactly as the vision caught him, fixed as a statue, insensible as a stone, and nothing could move him. The brethren would use pins and burning embers to recall him to his senses, but nothing could he feel. When he did revive and saw what had happened, he would call these visitations fits of giddiness, and ask them not to burn him again. Once a prelate, who had come to see him on some business, noticed that his hands were covered with sores. Joseph could not hide them, nor could he hide the truth, but he had an explanation ready.

“See, Father, what the brethren have to do to me when the fits of giddiness come on. They have to burn my hands, they have to cut my fingers, that is what they have to do.” And Joseph laughed, as he so often laughed; but we suspect that it was laughter keeping back tears.

His life became a series of visions and ecstasies, which could be triggered any time or place by the sound of a church bell, church music, the mention of the name of God or of the Blessed Virgin or of a saint, any event in the life of Christ, the sacred Passion, a holy picture, the thought of the glory in heaven, etc. Yelling, beating, pinching, burning, piercing with needles – none of this would bring him from his trances, but he would return to the world on hearing the voice of his superior in the order.

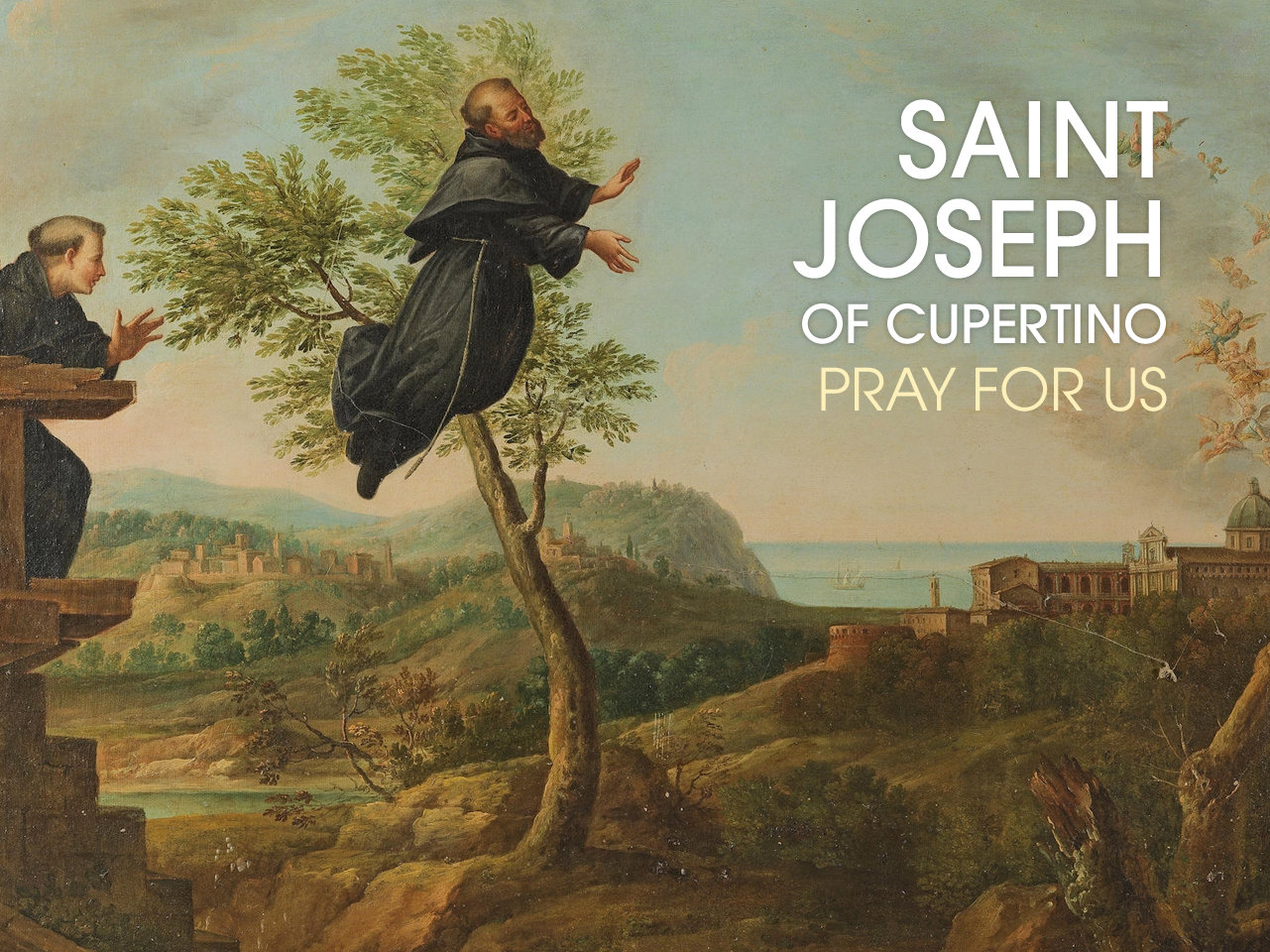

On October 4, 1630, the town of Cupertino held a procession on the feast day of Saint Francis of Assisi. Joseph was assisting in the procession when he suddenly soared into the sky, where he remained hovering over the crowd.

When he descended and realized what had happened, he became so embarrassed that he fled to his mother’s house and hid. This was the first of many flights, which soon earned him the nickname “The Flying Saint”.

Joseph’s life changed dramatically after this incident. His flights continued and came with increasing frequency. His superiors, alarmed at his lack of control, forbade him from community exercises, believing he would cause too great a distraction for the friary. For the fact was, Joseph could not contain himself. On hearing the names of Jesus or Mary, the singing of hymns during the feast of St. Francis, or while praying at Mass, he would go into a dazed state and soar into the air, remaining there until a superior commanded him under obedience to revive.

In the refectory, during a meal, Joseph would suddenly rise from the ground with a dish of food in his hands, much to the alarm of the brethren at table. When he was out in the country begging, suddenly he would fly into a tree. Once when some workmen were laboring to plant a huge stone cross in its socket, Joseph rose above them, took up the cross and placed it in the socket for them.

So concerned were Joseph’s brethren, they ordered him to be examined by the General of the Order. The Minister General could find no fault in Joseph. He took Joseph to see the Pope.

Joseph’s most famous flight allegedly occurred during the papal audience before Pope Urban VIII. When he bent down to kiss the Pope’s feet, he was suddenly filled with reverence for Christ’s Vicar on earth, and was lifted up into the air. Only when the Minister General of the Order, who was part of the audience, ordered him down was Joseph able to return to the floor.

Among other paranormal events associated with Joseph, he is said to have possessed the gift of healing. It is reported he once cured a girl who was suffering from a severe case of measles. Another story holds that an entire community suffering from a drought asked Joseph to pray for rain, which he did with success. He also dedicated himself to improving the spiritual lives of his fellow friars.

Not all of the friars whom Joseph lived with were well disposed towards him. Some superiors would scold Joseph for not accepting money and gifts offered to him for curing people, especially when they were members of the nobility. He would also find himself in trouble for returning home with a torn habit as a result of the people seeking relics who regarded him as a prophet and a saint.

Perhaps the most difficult time came when Joseph was the subject of an investigation by the Inquisition at Naples. Msgr. Joseph Palamolla accused Joseph of attracting undue attention with his “flights”, and claiming to perform miracles. On October 21, 1638, Joseph was summoned to appear before the Inquisition and, when he arrived, he was detained for several weeks. Joseph was eventually released when the judges found no fault with him.

Nervous and concerned about letting Joseph wander about at liberty with such powers and how that might upset ordered society, wanting to keep all of this hush-hush, Joseph’s superiors ordered him into seclusion. “Have I to go to prison?” he asked, as if he had been condemned. But in an instant he recovered. He knelt down and kissed the Inquisitor’s feet; then got into the carriage, smiling as usual as if nothing had happened.

After being cleared by the Inquisition, Joseph was sent to the Sacro Convento in Assisi. Though Joseph was happy to be close to the tomb of St Francis, he experienced a certain spiritual dryness. His flights came to a halt during this period.

Two years after his arrival at the Sacro Convento, Joseph was made an honorary citizen of Assisi and a full member of the Franciscan community. He lived in Assisi for another nine years. During this period Joseph was sought after by people (including ministers general, provincials, bishops, cardinals, knights and secular princes) who wanted to experience his divine consolation. He was happy to oblige, but the isolation of exile left him repressed. Believers were able to seek him out, but he was not allowed to preach or hear confessions, nor to join in the processions and festivities of feast days.

Over time, Joseph attracted a huge following. To stop this, Pope Innocent X decided to move Joseph from Assisi and place him in a secret location under the jurisdiction of the Capuchin friars in Pietrarubbia. Joseph was placed under strict orders to avoid writing letters, but he continued to attract throngs of people. This soon forced him to be moved to another location, this time to Fossombrone, which had little more success.

The ordeal finally ended when Pope Innocent X died, and the Conventual friars asked the newly elected Pope Alexander VIII to release Joseph from his exile and return him to Assisi. Alexander declined, and instead released Joseph to the friary in Osimo, where the Pope’s nephew was the local bishop. There, Joseph was ordered to live in seclusion and not speak to anyone except the Bishop, the Vicar General of the Order, his fellow friars, and, in case of a health crisis, a doctor. Joseph endured his ordeal with great patience. It is reported he did not even complain when a brother-cook neglected to bring him any food to his room for two days; this dull man whom no one could teach, and no one wanted, almost continually wrapt up in the vision of that which no man can express in words.

On August 10, 1663, Joseph became ill with a fever, but the experience filled him with joy. When asked to pray for his own healing he said, “No, God forbid!” He experienced ecstasies and flights during his last Mass which was on the Feast of the Assumption.

In early September, Joseph could sense that the end was near, so he could be heard mumbling, “The jackass has now begun to climb the mountain!” The ‘jackass’ was his own body.

Bedridden, there came constantly to Joseph’s lips the words of St. Paul: “Cupio dissolvi et esse cum Christo.” (Ph 1:23) Someone at the bedside spoke to him of the love of God; he cried out: “Say that again, say that again!” He pronounced the Holy Name of Jesus. He added: “Praised be God! Blessed be God! May the holy will of God be done!” The old laughter seemed to come back to his face; those around could scarcely resist the contagion. After receiving the last sacraments, a papal blessing, and reciting the Litany of Our Lady, Joseph Desa of Cupertino died on the evening of September 18, 1663.

He was buried two days later in the chapel of the Immaculate Conception before great crowds of people. Joseph was canonized on July 16, 1767, by Pope Clement XIII. In 1781, a large marble altar in the Church of St. Francis in Osimo was erected so that St. Joseph’s body might be placed beneath it; it has remained there ever since.

Even in the 17th century, there was interest in the unusual, and Joseph’s ecstasies in public caused both admiration and disturbance in the community. For 35 years he was not allowed to attend choir, go to the common refectory, walk in procession, or say Mass in church.

To prevent making a spectacle, he was ordered to remain in his room with a private chapel. He was brought before the Inquisition, and sent from one Capuchin or Franciscan house to another. But Joseph retained his joyous spirit, submitting to Divine Providence, keeping seven Lents of 40 days each year, never letting his faith be shaken. St Joseph of Cupertino, pray for us!

St. Joseph is the patron saint of those traveling by air, astronauts, and is the patron saint of pilots who fly for the NATO Alliance. He is the patron of paratroopers and those serving in the Air Force. He is also the patron of students taking exams. Cupertino, California, ranked as one of the most educated towns and world headquarters of Apple, Inc., is named after him. Cupertino boasts some of the highest ranked schools in the State of California, and has THE highest ranked highest ranked grammar school, Faria.

St. Joseph of Cupertino Church, stjoscup.org, is the Catholic parish in Cupertino, California. A life-sized bronze statue of St. Joseph in mid-flight was installed in the church prayer garden in 2006. The area where the city of Cupertino, California is today was first named in honor of St. Joseph of Cupertino on March 25, 1776, when Spanish explorers under Captain Juan Bautista de Anza camped in the area and named a small river for the Italian saint. The river is today known as Stevens Creek.

A 1962 film, “The Reluctant Saint”, starring Maximilian Schell and Ricardo Montalban was made about the life of St Joseph of Cupertino.

St. Joseph of Cupertino’s story was made into a children’s book called “The Little Friar Who Flew,” written by Patricia Lee Gauch, pictures by Tomie de Paola. It was published in 1980 by Peppercorn Publishers (soft cover) and G. P. Putnam’s Sons (hard cover), New York. ISBN (hardcover): 0-399-20714-7. ISBN (soft cover, large format): 0-399-20741-4.

A comic book, entitled The Flying Friar, was published by Speakeasy Comics in 2006, written by Rich Johnston, drawn by Thomas Nachlik, and edited by Tom Mauer. It is a fictionalization of the life of St Joseph, influenced heavily by the plotlines and characters of the Smallville TV series – St. Joseph is presented as a Clark Kent allegory, with his best friend turned worst enemy being the fictitious “Lux Luthor,” a supposed descendant of Martin Luther. (Mea culpa to the Lutherans on this distribution.)

Read the blog entries on this site reflecting prayers to and prayers answered through the intercession of St Joseph of Cupertino: http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=72. In the investigation preceding his canonization, 70 incidents of levitation were recorded.

Straight lines, see! 🙂 God is Great!!!!! Amen! Amen!

Prayer to St Joseph Cupertino

O Great St. Joseph of Cupertino, who while on earth did obtain from God the grace to be asked at your examination only the questions you knew, obtain for me a like favor in the examinations for which I am now preparing. In return I promise to make you known and cause you to be invoked.

Through Christ our Lord.

St. Joseph of Cupertino, pray for me.

O Holy Ghost, enlighten me

Our Lady of Good Studies, pray for me

Sacred Head of Jesus, Seat of divine wisdom, enlighten me.

Amen.

“Clearly, what God wants above all is our will which we received as a free gift from God in creation and possess as though our own. When a man trains himself to acts of virtue, it is with the help of grace from God from whom all good things come that he does this. The will is what man has as his unique possession.” – Saint Joseph of Cupertino, from the reading for his feast in the Franciscan breviary

-tomb of St Joseph of Cupertino, Osimo, Italy. Notice, please, how the angels hold aloft his sarcophagus.

Love,

Matthew

Sep 26 – St Marie-Victoire Therese Couderc, r.c., (1805-1885), Foundress of the Congregation of Our Lady of the Retreat of the Cenacle

“God always gives more than we ask.” -Saint Marie-Victoire Therese Couderc

I have been on retreat more than once at The Cenacle in Lincoln Park in Chicago, www.cenaclesisters.org/chicago/. Of course my first question, as would almost anyone’s would be, “What’s a cenacle?”

The Cenacle, from Latin “cenaculum”, also known as the “Upper Room”, is the site of The Last Supper. The word is a derivative of the Latin word “cena”, which means “dinner”. In Christian tradition, based on Acts 1:13(& 14), “When they arrived, they went upstairs to the room where they were staying. Those present were Peter, John, James and Andrew; Philip and Thomas, Bartholomew and Matthew; James son of Alphaeus and Simon the Zealot, and Judas son of James. They all joined together constantly in prayer, along with the women and Mary the mother of Jesus, and with his brothers.”

The “Upper Room” was not only the site of the Last Supper (i.e. the

Cenacle), but also the usual place where the Apostles stayed in Jerusalem, sometimes thought of as the first Christian church. Thus the Cenacle is considered the site where many other events described in the New Testament took place, such as:

- the Washing of the Feet by the Lord of the Apostles

- some Resurrection appearances of Jesus

- the gathering of the disciples after the Ascension of Jesus

- the election of Saint Matthias as apostle

- the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the disciples on the day of Pentecost

Not a bad place for a retreat? Huh? 🙂

Marie-Victoire Couderc was born in 1805 in Le Mas (Ardèche),

France. She made her novitiate with the Sisters of St. Regis in Lalouvesc (Ardèche) in 1825, taking the religious name Therese.

Concerned with welfare of female pilgrims visiting the shrine of St. John Francis Regis, SJ, in town, she co-founded the Sisters of the Cenacle with Father Jean-Pierre Etienne Terme in 1826. It was a response to the disruption and reawakening of the practice of the Faith in France due to the Revolution

St Therese became the Congregation’s founder Superior in 1828, and when the Mother House was established, its Superior General until 1838. The retreats increased rapidly and plans were made to build a new chapel and a new convent. But, after completion, the promised funding evaporated. The bishop of Viviers too quickly lost his trust in Therese, reinforcing Mother Therese’s own humble but mistaken conviction that she was to blame for the debacle. At last, she resigned her office of superior. She was thirty-three years old, having guided her sisters for the first ten years of the congregation’s existence.

Her successor, chosen by the Jesuit provincial, was Mademoiselle Gallet, a wealthy widow only 20 years old, who had been a novice for only 15 days, having entered on September 24, 1838, who hardly knew the first thing about being a nun, put the convent through a terrible trial. She made the rules more lax, Mother Therese had always insisted on silence and evangelical poverty, and borrowed money to buy beautiful things for the convent. Many nuns and outsiders were shocked at this new turn of events, but Our Lady was watching out for the little community.

When mademoiselle died later that year, she left her fortune to the

congregation. However, her relatives contested her will, and the

Cenacle’s financial situation was once more thrown into disarray. The Bishop of Viviers named Countess de la Villeurnoy the new Superior general. Soon, she even began to call herself “mother founder.”

The community of nuns as well as outside friends blamed Mother Thérèse for the whole affair. Rumors began to circulate. “They say that Therese is incompetent and has no business ability whatsoever. How can we count on her to raise funds for the congregation if she is going to fail like this? And her health is reported to be failing badly; perhaps she is no longer capable of governing. It is possible that she has mental problems.”

“It seems that no one can govern this congregation,” he began. “You

yourself resigned your office in disgrace, and this Countess has led you all to the brink of disaster. Now it falls to me to pick up the pieces.

Tell me: should I assign a new superior? Would it help this congregation function better?”

Mother Therese remained silent for a moment. “Fr Renault,” she said

carefully, “You know that I am a professed religious, and that I have taken a vow of obedience to my superiors for life. To me, that obedience means that I must respect every action of my superiors, whether it appeals to me or not. God has placed Mother de la Villeurnoy in a position of authority over me; you seek testimony which I cannot give nor do I wish to give.”

The provincial was dumbfounded. “But this woman calls herself the founder! She has stolen the respect that is rightfully yours!” he burst out.

“Perhaps,” Mother Therese said quietly. “But more important than any title is the vow which I have made to my Creator and Redeemer.”

Nevertheless, the provincial did not need her testimony; there was more than enough evidence against the Countess. After causing eleven months of havoc, the Countess was removed from office.

Mother Contenet, her replacement, eager to attract members of the higher social classes for the congregation, expelled ten of the original twelve members of the congregation. Convinced of the ineptitude of the true founder, she did everything in her power to keep Mother Therese away from the other sisters. Therese was exiled from her chosen work of giving retreats to spend thirteen years at the most difficult manual labor in the congregation, working in the gardens and the cellar. Conditions were so poor that her eyesight was permanently impaired. Her food was only the worst of the vegetables and the unwanted remnants of black bread which the gardener threw alongside the convent wall.

Mother Therese dropped into increasing obscurity. “After all,” she

reflected, “the religious life is a sufficiently great grace even though one purchase it at the price of the most difficult of sacrifices.” Despite the great mortification of her state, she told the young religious that “We should never allow even one thought of sadness to enter the soul. Have we not within us Him who is the joy of Heaven!”

Mother Therese’s exile ended with the death of Mother Contenet in 1852, but dissension and instability once more returned to the Cenacle. Mother Anaïs was elected the new superior general, but left the congregation three years later. Not until 1856 did Therese return to an active role in the congregation.

During a time of crisis, Mother Therese was sent briefly to serve as temporary superior of the convent in Paris and then at Tournon, where her governance was remembered for its firmness but genuine goodness. Again, however, she disappeared into the background.

One day, while visiting one of the convents of the Religious of the

Cenacle, Cardinal Lavigerie noticed Mother Therese praying in the chapel. He turned to the superior of the house and asked, “Anyone can see how holy the face of this sister is. What is her name?”

“Sister Therese Couderc,” was the reply.

“She seems such a saint,” he mused. “What is her place in the history of the congregation?”

The superior was embarrassed. “Well, she was in charge of the gardens for many years, and she was sent to be a temporary superior at two houses in the 1850’s. Now she just mostly prays in the chapel, and we let her alone.”

Cardinal Lavigerie looked at her sharply. “She has been left out, hasn’t she?” The superior said nothing.

Her reputation had been by now so thoroughly maligned by her superiors that even her status as founder had been completely forgotten. Her work as founder had been, above all, her prayers, penances, and humiliation. It was only towards the end of her life, when the bishop of Viviers launched an inquiry into the circumstances of the foundation, that Mother Therese Couderc was finally recognized as the founder of the Sisters of the Cenacle. Fra Angelico’s “The Mocking of Christ” comes to mind.

Mother Thérèse spent many years at the convent in Fourvière, being in charge of the manual labour. She describes some of these trying times…..“We gathered up pieces of black bread which a man used to throw beside the convent wall. At night and early morning we had only one lamp in the hall to give us light to dress by and we had very poor light to work by at recreation.”

Therese told the younger nuns, “Great trials make great souls

and fit them for the great things which God wishes to do through them…Let us say bravely and confidently: God is sufficient for me!…We should never allow even one thought of sadness to enter the soul, because we have within us, Jesus, the Joy of Heaven!”

In 1864, God made Therese understand that souls would not do enough prayer and penance. She wanted to save souls and she firmly believed in self-surrender. Mother Thérèse said, “There is sweetness and peace when one gives himself totally to God, and by doing this, the soul finds Heaven on earth!”

Mother Thérèse spent the last ten years of her life in much suffering of body and soul. In 1875, she offered herself to Our Lord as a victim soul. Day after day, but especially on Thursdays and Fridays, she shared Our Lord’s Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane. She would stay in the chapel near the altar and weep for hours on end, saying over and over, “Have pity on me Dear Lord, have pity on me!”

Her sufferings increased and by 1885, Mother Thérèse had to stay in her. In her pains she suffered patiently and suffered with great peace of. It is reported by a contemporary biographer, Mother Therese stated that the Poor Souls in Purgatory would often come to visit her and they would sing with great love and humility, the “Te Deum.” On September 26, 1885, Mother Thérèse died, closing her eyes to this world. Like a number of founders and foundresses, she later was honored for her sanctity. She died in Lyon at age 80 and is buried in Lalouvesc.

———————-

The modern day sisters of the the Cenacle, 1500 members in sixteen countries, possess a compelling love for Jesus Christ and try to find the best means of making Him better known and loved through their ministry of spiritual direction, personal, private, Ignatian, and directed retreats, particularly in the retreat centers they administer. By membership in their Congregation they give their word to God and each other to continue their search to live the Gospel in the society of today. Not a bad promise to make, IMHO.

During your retreat, you may request a Cenacle sister as a spiritual companion. The Irish have the expression Kelly and I have inscribed on the inside of our wedding rings, “Anam Cara”=”soul friend”. A Cenacle sister, if requested, may, as a trained and experienced spiritual companion, support you in:

- Exploring the “desires of your heart” by talking about your life and your relationship with God.

- Encouraging you in your prayer.

Becoming aware of God’s action in the events of your life and your inner journey. - Reverencing and savoring your experience of God.

- Listening to the deepest desires of your heart.

- Trusting in the Holy Spirit to help you find within yourself the answers to your deep questions.

- Discerning a direction for your life that is in harmony with God’s dream for you.

For me, prayer is like breathing. I absolutely need it. I depend on upon it. Nothing works without it. It must be first. It has become more intense with time and graces received. To rest, completely. To be refreshed, wonderfully. Relationships are very important, we all realize, especially that One. Why should its deepening be any different than our deepening with others, in time spent together, speaking tenderly, lovingly with one another? With Him?

———————-

“I have just one desire, that God be glorified.”

-Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc

“My heart embraces the whole world.”

-Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc

“Let me live by love, let me die of love, and let my last heartbeat be an act of the most perfect love.”

-Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc

“All places are alike to me, because everywhere I expect to find God, who is the only object of all my desires.”

-Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc

“What does it matter if my feet, bare and torn, fill my wooden shoes with blood? I would willingly begin the journey all over again, for I have indeed found the good God!”

-Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc

“I abandon myself with my whole heart to God’s will, and to God’s good pleasure — and when I have in all sincerity made this act of

self-surrender, I experience great tranquility and perfect peace.” –Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc

“I could say, with you, that my heart doesn’t age in this matter of loving others…. We know well we have the same heart we had earlier; it always knows how to love God first and then others in [God]….” –Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc

“I saw written as in letters of gold this word Goodness, which I repeated for a long while with an indescribable sweetness. I saw it, I say, written on all creatures, animate and inanimate, rational or not, all bore this name of goodness. I saw it even on the chair I was using as a kneeler. I understood then that all that these creatures have of good and all the services and helps that we receive from each of them is a blessing that we owe to the goodness of our God, who has communicated to them something of his infinite goodness, so that we may meet it in every thing and everywhere.” -Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc

“I was preparing to begin my meditation, when I heard the pealing of the church bells calling the faithful to attend the divine Mysteries. At that moment the desire came over me to unite myself with all the Masses which were being said, and to that end I directed my intention so that I might participate in them.

Then I had an overall view of the whole Catholic world and a multitude of altars upon which at one and the same time the adorable Victim was being immolated. The blood of the Lamb without stain was flowing abundantly over every one of these altars, which seemed to be surrounded by a light cloud of smoke ascending toward heaven. My soul was seized and penetrated with a feeling of love and gratitude on beholding this most abundant satisfaction that Our Lord was offering for us.

But I was also greatly astonished that the whole world was not sanctified by it. I asked how it could be that the sacrifice of the Cross having been offered only once was sufficient to redeem all souls, while now being renewed so often it was not sufficient to sanctify them all.

This is the answer I thought I heard: The sacrifice is without any doubt sufficient by itself, and the Blood of Jesus Christ more than sufficient for the sanctification of a million worlds, but souls fail to correspond, they are not generous enough. Now the great means by which one may enter into the path of perfection and of holiness is to SURRENDER ONESELF to our good God.

But what does it mean to SURRENDER ONESELF?

I understand the full extent of the expression TO SURRENDER ONESELF, but I cannot explain it. I only know that it is very vast, that it embraces both the present and the future.

TO SURRENDER ONESELF is more than to devote oneself, more than to give oneself, it is even something more than to abandon oneself to God. In a word, to SURRENDER ONESELF is to die to everything and to self, to be no longer concerned with self except to keep it continually turned toward God.

TO SURRENDER ONESELF is, moreover, no longer to seek oneself in anything, either for the spiritual or the physical, that is to say, no longer to seek one’s own satisfaction, but solely the divine good pleasure.

It should be added that to SURRENDER ONESELF is also to follow that spirit of detachment which clings to nothing, neither to persons nor to things, neither to time nor to place. It means to adhere to everything, to accept everything, to submit to everything.

But perhaps you will think that this is very difficult to do. Do not let yourself be deceived. There is nothing so easy to do, nothing so sweet to put into practice. The whole thing consists in making a generous act once and for all, saying with all the sincerity of your soul: “My God, I wish to be entirely thine; deign to accept my offering.” And all is said. But from then on, you must take care to keep yourself in this disposition of soul and not to shrink from any of the little sacrifices which can help you advance in virtue. You must always remember that you have SURRENDERED yourself.

I pray to our Lord to give an understanding of this word to all souls desirous of pleasing him and to inspire them to take advantage of so easy a means of sanctification. Oh! If people could just understand ahead of time the sweetness and peace that are savored when nothing is held back from the good God! How he communicates himself to the one who seeks him sincerely and has known how to SURRENDER herself. Let them experience it and they will see that here is found the true happiness they are vainly seeking elsewhere.

The SURRENDERED soul has found paradise on earth, since she enjoys that sweet peace which is part of the happiness of the elect.” –To Surrender Oneself, by Saint Marie Victoire Therese Couderc, 26 June 1864

“Not my will be done, but God’s. That is my favorite prayer which I mean to pray every day as long as there is breath left in me, because it is the one which gives me and leaves me with the greatest peace of soul.”

-letter to Mother Marie Aimee Lautier, 16 Oct 1881

“Surrender myself, that is all I did during this retreat – the good God did all rest.”

-letter to Mother de Larochenegly, 13 Feb 1864

“I abandon myself sincerely to God’s will and good pleasure, and when I have sincerely made this act of abandonment, I am calm and I experience a great peace.”

-letter to Mother de Larochnegly, 25 Nov 1875

I learned the necessary interchangeability of the words “Christian faith” and “surrender to Him” many years ago, in prayer. Not easy, just necessary, required. There is no other way to peace.

Prayer for the intercession of St Therese Couderc

O Good God

We rejoice with St Therese Couderc

To find your goodness all around us

And to know that you desire only good for us.

In your great love,

Grant us the favor we ask

And the grace to receive

With your servant Therese

The gift of Christ-like surrender to God.

Amen.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTRFUFpV6J4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G-V-rqnyZxI

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ieluPY8H6oY

-the Cenacle in Jerusalem

Love,

Matthew

Sep 17- St Hildegard von Bingen, OSB, (1098-1179), Doctor of the Church

-please click on the image for greater detail

Saint Hildegard of Bingen, O.S.B. (German: Hildegard von Bingen; Latin: Hildegardis Bingensis) (1098 – 17 September 1179), also known as Saint Hildegard, and “Sibyl of the Rhine”, was a German writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, Benedictine abbess, visionary, and polymath. Elected a magistra by her fellow nuns in 1136, she founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg in 1150 and Eibingen in 1165. One of her works as a composer, the Ordo Virtutum, is an early example of liturgical drama and arguably the oldest surviving morality play. She wrote theological, botanical and medicinal texts, as well as letters, liturgical songs, and poems, while supervising brilliant miniature Illuminations.

On 10 May 2012, Pope Benedict XVI extended the liturgical cult of St. Hildegard to the universal Church, in a process known as “equivalent canonization”. On 27 May 2012, the Pope announced that, on 7 October 2012, he will declare St. Hildegard to be the 35th Doctor of the Church.

Hildegard’s date of birth is uncertain. It has been concluded that she may have been born in the year 1098. Hildegard was raised in a family of free nobles. She was her parents’ tenth child, sickly from birth. In her “Vita”, or brief biography often written for saints, Hildegard explains that from a very young age she had experienced visions.

Perhaps due to Hildegard’s visions, or as a method of political positioning, Hildegard’s parents, Hildebert and Mechthilde, offered her as an oblate to the church; their “tithe” to the Church. The date of Hildegard’s enclosure in the church is contentious. Her Vita tells us she was enclosed with an older nun, Jutta, at the age of eight. However, Jutta’s enclosure date is known to be in 1112, at which time Hildegard would have been fourteen. Some scholars speculate that Hildegard was placed in the care of Jutta, the daughter of Count Stephan II of Sponheim, at the age of eight, before the two women were enclosed together six years later. There is no written record of the twenty-four years of Hildegard’s life that she was in the convent together with Jutta. It is possible that Hildegard could have been a chantress and a worker in the herbarium and infirmary.

In any case, Hildegard and Jutta were enclosed at Disibodenberg in the Palatinate Forest in what is now Germany. Jutta was also a visionary and thus attracted many followers who came to visit her at the enclosure. Hildegard also tells us that Jutta taught her to read and write, but that she was unlearned and therefore incapable of teaching Hildegard Biblical interpretation. Hildegard and Jutta most likely prayed, meditated, read scriptures such as the psalter, and did some sort of handwork during the hours of the Divine Office. This also might have been a time when Hildegard learned how to play the ten-stringed psaltery. Volmar, a frequent visitor, may have taught Hildegard simple psalm notation. The time she studied music could also have been the beginning of the compositions she would later create. Upon Jutta’s death in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously elected as “magistra” of the community by her fellow nuns.

With regard to her visions, Hildegard says that she first saw “The Shade of the Living Light” at the age of three, and by the age of five she began to understand that she was experiencing visions. She used the term ‘visio’ to this feature of her experience, and recognized that it was a gift that she could not explain to others. Hildegard explained that she saw all things in the light of God through the five senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Hildegard was hesitant to share her visions, confiding only to Jutta, who in turn told Volmar, Hildegard’s tutor and, later, secretary.

Throughout her life, she continued to have many visions, and in 1141, at the age of 42, Hildegard received a vision she believed to be an instruction from God, to “write down that which you see and hear.” Still hesitant to record her visions, Hildegard became physically ill. The illustrations recorded in the book of “Scivias” were visions that Hildegard experienced, causing her great suffering and tribulations. In her first theological text, “Scivias” (“Know the Ways”), Hildegard describes her struggle within:

“But I, though I saw and heard these things, refused to write for a long time through doubt and bad opinion and the diversity of human words, not with stubbornness but in the exercise of humility, until, laid low by the scourge of God, I fell upon a bed of sickness; then, compelled at last by many illnesses, and by the witness of a certain noble maiden of good conduct [the nun Richardis von Stade] and of that man whom I had secretly sought and found, as mentioned above, I set my hand to the writing. While I was doing it, I sensed, as I mentioned before, the deep profundity of scriptural exposition; and, raising myself from illness by the strength I received, I brought this work to a close – though just barely – in ten years…And I spoke and wrote these things not by the invention of my heart or that of any other person, but as by the secret mysteries of God I heard and received them in the heavenly places. And again I heard a voice from Heaven saying to me, ‘Cry out therefore, and write thus’

Hildegard’s Vita was begun by Godfrey of Disibodenberg under Hildegard’s supervision. It was between November 1147 and February 1148 at the synod in Trier that Pope Eugenus heard about Hildegard’s writings. It was from this that she received Papal approval to document her visions as revelations from the Holy Spirit giving her instant credence.

Before Hildegard’s death, a problem arose with the clergy of Mainz. A man buried at the convent in Rupertsburg had died after excommunication from the Church. Hildegard saw to it the man had received the last rites. But, the clergy wanted to remove his body from the sacred ground. Hildegard did not accept this idea, replying that it was a sin and that the man had been reconciled to the Church at the time of his death. She claimed she’d received word from God allowing the burial. But her ecclesiastical superiors intervened, and ordered the body exhumed. Hildegard defied the authorities by hiding the grave, and the authorities excommunicated the entire convent community. Most insultingly to Hildegard, the interdict prohibited the community from singing. She complied with the interdict, avoiding singing and communion, but did not comply with the command to exhume the corpse. Hildegard appealed the decision to yet higher Church authorities, and finally had the interdict lifted.

On 17 September 1179, when Hildegard died, her sisters claimed they saw two streams of light appear in the skies and cross over the room where she was dying.

Hildegard’s musical, literary, and scientific writings are housed primarily in two manuscripts: the Dendermonde manuscript and the Riesenkodex. The Dendermonde manuscript was copied under Hildegard’s supervision at Rupertsberg, while the Riesencodex was copied in the century after Hildegard’s death.

Attention in recent decades to women of the medieval Church has led to a great deal of popular interest in Hildegard, particularly her music. In addition to the Ordo Virtutum, sixty-nine musical compositions, each with its own original poetic text, survive, and at least four other texts are known, though their musical notation has been lost. This is one of the largest repertoires among medieval composers. Hildegard also wrote nearly 400 letters to correspondents ranging from Popes to Emperors to abbots and abbesses; two volumes of material on natural medicine and cures; an invented language called the Lingua ignota; various minor works, including a gospel commentary and two works of hagiography; and three great volumes of visionary theology: Scivias, Liber vitae meritorum (“Book of Life’s Merits” or “Book of the Rewards of Life”), and Liber divinorum operum (“Book of Divine Works”).

In December 2010, BXVI quoted a long passage from one of Hildegard’s visions to assess the damage done to the church by the sex abuse scandal, and to invite the Vatican hierarchy to accept this “humiliation” as an “an exhortation to truth and a call to renewal”.

“In the vision of St. Hildegard, the face of the church is stained with dust. … Her garment is torn — by the sins of priests. The way she saw and expressed it is the way we have experienced it this year,” the Pope said.

A few months earlier, he had referred to Hildegard to address calls for reform inside the Church, sparked by the “abuses of the clergy.” Benedict recalled how the saint had “harshly reprimanded” those who in her lifetime wanted “radical reform,” reminding them that “true renewal” comes from “repentance” and “conversion, rather than with a change of structures.”

In Hildegard’s lifetime, Pope Eugenius III, who needed help fending off the Cathar heresy that rejected the Church’s worldly power, recognized the authenticity of her visions and authorized her to preach in public — something that Church doctrine had officially forbidden until that time and that nonetheless remains controversial in Catholicism. Hildegard used her unprecedented role to publicly rebuke the emperor and to call on the Pope and bishops to reform the Church’s ills.

In 2006, Benedict XVI himself drew on Hildegard to expound his thinking on women’s role in the Church: not as priests but as bearers of a “spiritual power” that enables them to, yes, even “criticize the bishops.”

In space, she is commemorated by the asteroid 898 Hildegard.

“Listen: there was once a king sitting on his throne. Around him stood great and wonderfully beautiful columns ornamented with ivory, bearing the banners of the king with great honor. Then it pleased the king to raise a small feather from the ground, and he commanded it to fly. The feather flew, not because of anything in itself but because the air bore it along. Thus am I, a feather on the breath of God.” – St Hildegard of Bingen

O leafy branch,

standing in your nobility

as the dawn breaks forth:

now rejoice and be glad

and deign to set us frail ones

free from evil habits

and stretch forth your hand

and lift us up.

-St Hildegard von Bingen

O ruby blood

which flowed from on high

where divinity touched.

You are a flower

that the winter

of the serpent’s breath

can never injure.

-St Hildegard von Bingen

O Shepherd of souls

and o first voice

through whom all creation was summoned,

now to you,

to you may it give pleasure and dignity

to liberate us

from our miseries and languishing.

-St Hildegard von Bingen

O eternal Lord,

it is pleasing to you

to burn in that same fire of love,

like that from which our bodies are born,

and from which you begot your Son

in the first dawn before all of Creation.

So consider this need which falls upon us,

and relieve us of it for the sake of your Son

and lead us in joyous prosperity

-St Hildegard von Bingen

O Great Father we are in great need;

Now therefore we implore, we implore you

Through your Word, by which you have

Filled us with [those things] we need;

Now it may please you Father for it befits you

To consider us with your help,

So that we might not fail and lest your name

Might be blackened in us

And through your name, deign to help us.

-St Hildegard von Bingen

“You are encircled by the arms of the mystery of God.” -St. Hildegard of Bingen

“May the Holy Spirit enkindle you with the fire of His Love so that you may persevere, unfailingly, in the love of His service. Thus you may merit to become, at last, a living stone in the celestial Jerusalem.”

–St. Hildegard von Bingen

Prayer for the intercession of St Hildegard von Bingen:

O God, by Whose grace Thy servant Hildegard, enkindled with the fire of Thy love, became a burning and shining light in Thy Church: Grant that we also may be aflame with the spirit of love and discipline, and may ever walk before Thee as children of light; through Jesus Christ our Lord, Who with Thee, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, liveth and reigneth, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8gK0_PgIgY

In 2009, Zeigeist Films released “Vision”, a film on the life of St Hildegard von Bingen: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0995850/

Love,

Matthew

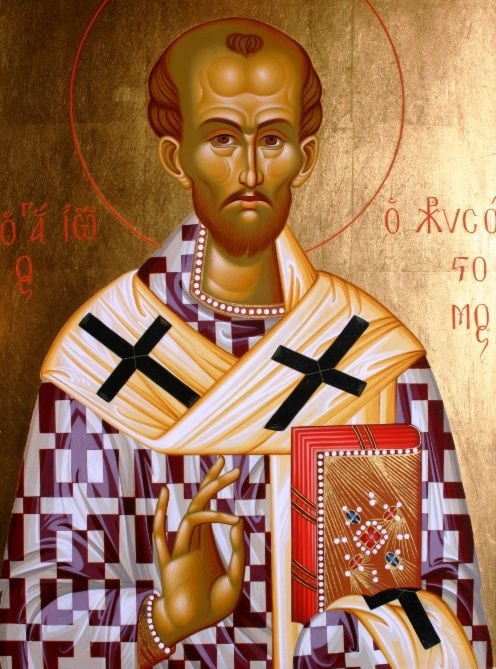

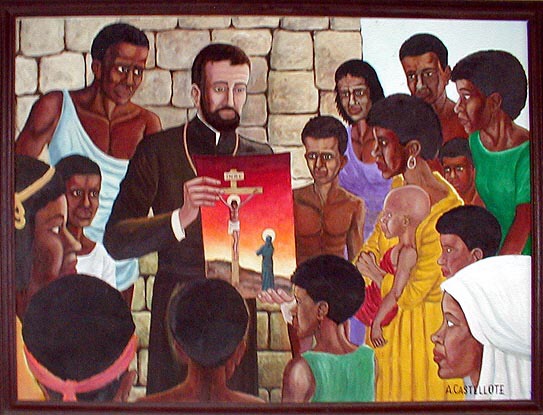

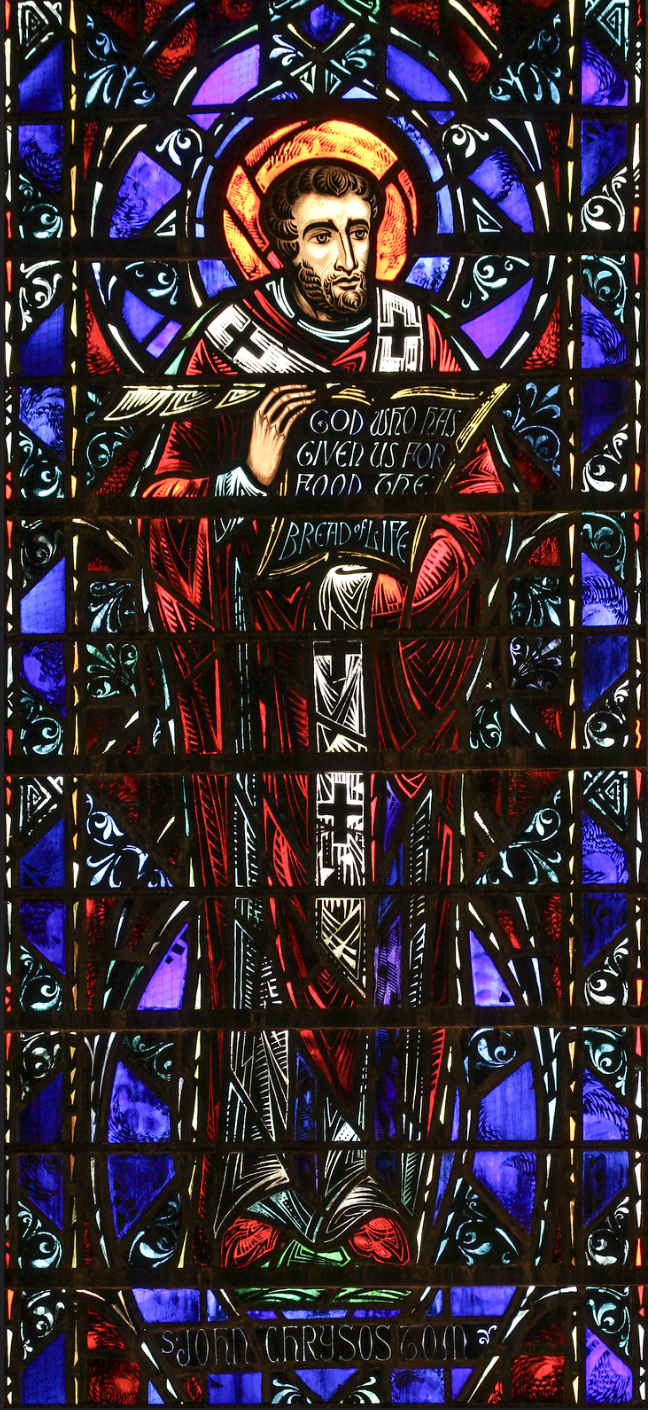

Sep 13 – St John Chrysostom, (347-407 AD), Archbishop of Constantinople, Doctor of the Church, Doctor of Preachers, The Real Presence

-please click on the image for greater detail

Quick! Name your favorite top ten living great Catholic preachers! Five? One? I trust I make my point. St John Chrysostom was one. Called “Golden-mouthed=Chrysostom”.