-St Marie-Marguerite d’Youville, SGM

I LOVE MARRIED SAINTS!!!!! And, Kelly, don’t be nervous, I know you’re not the nervous type. I used to be desperately in love with a girl from Charlotte, NC, named Marguerite. One of my many broken hearts. (Ahhhhhhhhh) 🙂 Thank God things work out God’s way and not ours! Thank GOD for unanswered prayers I say the older I get. His will is perfect. I LOVE YOU SOOOO MUCH Kelly Marie! 🙂 XOXOXO!!!!

Marguerite d’Youville, the first native Canadian to be elevated to sainthood, was born October 15, 1701 at Varennes, Quebec. Marguerite was baptized the next day at St. Anne’s parish church. After her baptism, her father placed her on the knees of her maternal great-grandfather, Pierre Boucher, for the traditional blessing: “May God bless you, my little one, as I bless you!”

Marguerite was the eldest of six children born to Lieutenant Christophe Dufrost de Lajemmerais and Marie-Renée Gaultier. Lieutenant Lajemmerais was promoted to the rank of Captain, in June 1705. This was the highest rank that a soldier of the French colonial troops could attain. He was promoted because of his fidelity to his duty, his spirit of self-sacrifice, his prompt willingness to take any assignment.

On June 1, 1708, Marguerite’s childhood was tragically disrupted by the death of her father. This was a time of insecurity. The salary of Captain de Lajemmerais had been large enough to keep his growing family but not sufficient to provide savings for the future. Marguerite learned very early how to think of others as she helped her mother provide for her destitute family. Marie Renée now had to depend on the charity of others for the needs of her children. And worse still – it would be another six years before she would receive a widow’s pension. This was due to complex formalities and slow communication between France and her colony of Canada.

Because she was extremely intelligent, Marguerite was greatly admired by her great-aunt, Mother St. Pierre, an Ursuline nun, and several other persons. So in 1712, in order to pursue her studies, Marguerite was taken in a little rowboat to the boarding school at the Ursuline Convent, in Quebec City; some hundred and fifty miles away.

There she received a good education from the nuns and also a good spiritual training. At the convent school, Marguerite was a strong young girl with an attractive personality and she was admired for a goodness and a maturity, well beyond her age. She acquired the habit of meditating daily on some page of a little book dealing with the “Holy Ways of the Cross”.

In 1714, at the age of almost 13, after two years at the boarding school, Marguerite received her First Holy Communion. But the girl could not stay in the convent for a lengthy time. Mme. Lajemmerais could not afford to leave Marguerite in Quebec any longer, even with the help of relatives and friends. There were still five other children to be educated. So our friend was obliged to go back to Varennes that same year, to help at home and to teach her brothers and sisters. Marguerite was an invaluable help to her mother. By her handiwork, she contributed skillfully to the support of the family and often, as she was making fine lace, she would tell wonderful stories to her brothers and sisters.

As a young woman, Marguerite became very popular in the social life of Varennes. At 18, she got engaged to a young man whom she deeply loved. But the promise of a happy marriage ended abruptly when her mother remarried beneath her social class one Timothy Sullivan, an Irish doctor who was seen by the townspeople as a disreputable foreigner, an act that was unacceptable to the family of Marguerite’s fiancé. We can imagine the heartbreak of the frustrated betrothed. Marguerite’s family fell out of favor with people in their home town and so two years later moved to Montreal.

In Montreal, Marguerite became associated with the aristocracy of old Montreal who in time noticed that she was graceful, well mannered, serious and reserved. Before long, Marguerite met François d’Youville and once again, fell in love.

-François d’Youville (1700-1730)

Marguerite married François d’Youville 12 August 1722 and the young couple made their home with Francois’ mother, an avaricious and domineering woman who made life miserable for Marguerite. During the frequent absences of her husband, Marguerite’s mother-in-law was most unsympathetic towards her.

Marguerite soon came to realize that her husband had no interest in making a home life. François was indifferent, selfish and covetous; he was interested only in making money! His frequent absences, bootlegging, and illegal liquor trading with the Indians for furs caused her great suffering, making her endure the slurs and taunts of her neighbors. He was even absent at the birth of their first child.

But in spite of all these sorrows, Marguerite remained faithful to the her duties of state, always treating François with respect, and favoring him with all kind of delicate attentions. It was during these sorrowful times, in 1727, that the holy woman received a special grace from God. She came to a deep realization that God is a Father who has every human being in His providential care and that all are brothers and sisters. Through her whole life Marguerite kept this thought in her mind: “I leave all to Divine Providence, my confidence is in it; all will happen which is pleasing to God.”

She was pregnant with her sixth child when François became seriously ill. She faithfully cared for him until his death in 4 July 1730, leaving her with his enormous debts. By age 29, she had experienced desperate poverty and suffered the loss of her father and husband. Four of her six children had died in infancy. In 1734, she started to suffer from a mysterious ailment in her knees. It would only get worse through the years, and would make her suffer greatly, but would not stop her from doing her charitable work.

In all these sufferings Marguerite grew in her belief of God’s presence in her life and of His tender love for every human person. She, in turn, wanted to make known His compassionate love to all. She undertook many charitable works with complete trust in God, Who she loved as a Father.

She provided for the education of her two sons, who later became priests, by opening a small dry-goods storefront on the first floor of her home where she sold her own handiwork and household goods. She paid off all her inherited debts. On November 21, 1737 Marguerite welcomed a blind woman into her home. She spent much of her profits helping those even poorer than herself. She begged for money to bury criminals who had been hung in the market place.

One day, Marguerite’s spiritual director, Fr. Dulescoat, told her, “Be comforted my child, God destines for you a great work and you will raise up a house from its ruins!” God would make His plans fully known to her at a later time. Providence. The trust in Providence.

Seeing Marguerite selflessly caring for the poor, inspired three women to join her. On December 31, 1737, Catherine Cusson, Louise Thaumur la Source, and Catherine Demers joined Marguerite. They consecrated themselves to God, promising secretly to serve Jesus in His poor.

Completely dedicated to her mission of charity, Madame d’Youville rented a larger house to receive the poor. She and her three companions entered this house on October 30, 1738. As they stepped into their new place, their first act was to kneel before the statue of Our Lady of Providence. They placed their work of helping the poor under the protection of Our Lady, and consecrated themselves to God, to serve the poor and most destitute members of her Divine Son, till the end of their lives. Marguerite was 37 years old. They received the help of Father Louis Normant du Faradon. Marguerite, without even realizing it, had become the foundress of the Sisters of Charity of the General Hospital of Montreal, “Grey Nuns”.

Like other saints, the members of the little society were persecuted and contradicted. People were even more disturbed over the opening of this house. Two days after its opening, on All Saints day, they threw stones at Madame d’Youville and her companions on their way to church! Their maliciousness went even further when they heard rumors that Fr. Louis Normant, the Superior of the Sulpicians – and Marguerite’s new spiritual director, wanted her and her companions to take over Montreal’s General Hospital for the poor, established in 1693 by the Charon Brothers! The people had other plans for the dilapidated hospital.

Even Marguerite’s own relatives and friends were shocked by what she was doing and questioned her motives – her two brothers-in-law even signed a petition addressed to the Secretary of State, opposing such a move. Class-consciousness was strong in her culture, in those days, and Marguerite had started something that was just not done by persons of her standing.

Even the local parish priest believed in the calumnies made against the little community, and refused to give its members Holy Communion! But despite these persecutions, Mother d’Youville and her companions remained peaceful, and continued working devotedly and courageously, finding their best support through prayer. It was when things looked the most desperate that Marguerite was most trusting in God’s help, and felt most His closeness to her.

Marguerite always fought for the rights of the poor and broke with the social conventions of her day. It was a daring move that made her the object of ridicule and taunts by her own relatives and neighbors. Even though her husband had passed away, the society Marguerite lived in still judged her by the illegal actions of her deceased husband. Some called Marguerite and her companions “Les Soeurs Grises”, which can mean “the grey women/nuns”, but which also means “the drunken women/the tipsy nuns”. “Grises”, in French, can mean “grey” or “drunk”. This was in reference to d’Youville’s late husband. The neighbors suspected the small community of manufacturing alcohol in their home. Love thy neighbor? How about the neighbors let the dead bury their dead and let the dead past die?

But, as is so often the case with God, the slur of ridicule, with His grace, is transformed into the adulation of praise, respect, and reverence. Later, when the work of these women became well respected, Mother Marguerite chose grey as the color of their habit to remind those who slandered them of their verbal abuse.

Marguerite persevered in caring for the poor despite many obstacles. On February 20, 1741, Sr. Catherine Cusson died of tuberculosis at the age of 32. During the three short years of her religious life, she was distinguished by her charity to the poor and by her exact observance of the rule.

To Marguerite, the loss of this spiritual daughter was as painful as that of her natural children had been. And even while the weight of Sr. Catherine’s death weighed in the hearts of the nuns, another threatened loss of far greater weight sent the Sisters to their knees in urgent prayer. Fr. Normant, their Superior, had become so dangerously ill that any hope of his recovery was almost abandoned.

Pounding on the doors of Heaven, Marguerite solemnly promised that if Fr. Normant were restored to health, she would have a votive light burned before the Blessed Sacrament every year on the Feast of the of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary – a feast of deep significance to the Sulpicians. Moreover she promised to have a special painting made of the Eternal Father by an artist in France. This was a promise that would be quite costly for the struggling community, but no sacrifice was too great for the life of their beloved director. Fr. Normant recovered his health – and since then, a beautiful painting of the Eternal Father, painted by Challe in 1741, hangs in the vast community room in the Motherhouse in Montreal. For some time our friend was also praying for the healing of her knees, not because of the suffering, but rather of the impossibility she had to continue to work. Here again, she was miraculously healed one day.

Marguerite and her companions were now sharing their home with three boarders and ten destitute persons. All were living happily in their cramped quarters but suddenly their joy turned to sorrow when during the night of January 31, 1745, a fire completely destroyed their home. It was devastating to the residents, but Marguerite promised them that she would not abandon them. With unwavering trust in Divine Providence, she resolved to start over. While the fire was raging, a group of bystanders were heard to shout: “Look at those purple flames! … Those women are drunk!” By humility, and to show her nuns should be inebriated by the love of God and neighbor, Marguerite kept that nickname for her community. This tragedy only served to deepen her commitment to the poor. Marguerite asked herself, “What can we learn from this? … Perhaps we have been too well off. Now we will have to live more poorly!”

Two days later, on February 2, 1745, she and her two early companions pledged themselves to put everything in common in order to help a greater number of persons in need. At age 44, Marguerite and the other Sisters, signed the “Original Commitment”. Part of this founding document reads: … “for the greater glory of God … for the relief of the poor … we are united in pure charity to live and die together … to consecrate without reserve our time, our days, indeed our entire life, to labor … to receive, feed and support as many poor as we can take care of …” And since that day, every Grey Nun has signed her name to this commitment!

Two years later, this “mother of the poor” as she was called, was asked to become director of the Charon Brothers Hospital in Montreal which was falling into ruin and deeply in debt. On October 7, 1747, a small procession made its way toward the General Hospital of Montreal. Marguerite had been appointed temporary director of the General Hospital, which was falling into ruins. It was a last resort; as nobody could be found to administer this neglected institution. Marguerite, who was too weak to walk, was seated on an old mattress in a cart. She had to travel this way as she was exhausted after the stress of the recent fire and the frequent moves that followed. Her companions, some aged people and an orphan followed her on foot. And at the same time poor Marguerite had to endure the laughing of the people they passed by. Arriving at the hospital, Marguerite found that four elderly men and two aged Brothers were living there under deplorable conditions. After attending to their urgent needs, Marguerite’s creative ingenuity and the energetic activity of her sisters made the hospital livable. After only three years as Director of the General Hospital, Marguerite had completely renovated it. Marguerite would live in this hospital for the rest of her life. It became a beacon for outcasts.

A new difficulty for the foundress would soon make its appearance; the work still had enemies, and in 1750 plans were made, without consulting her, to merge it with another of similar nature, staffed by the nursing nuns of Quebec City. Marguerite was therefore sadly surprised when she was in the market place one day, and heard by a public announcement that the General Hospital was to be merged with the one in Quebec, where its poor people were to be transferred!

The authorities had decided that there was need for only one hospital of this kind. But Marguerite is convinced: The General Hospital belongs to those who need it badly: the poor! She therefore tried all she humanly can to have the decision changed.

-Bishop Henri de Pontbriand (1708-1760)

But the opposition of Intendant François Bigot, representative of the King of France, and the disapproval of Bishop de Pontbriand of Quebec, was a heavy blow to Marguerite. She tried to soften the impact of this news on her sisters and their charges: “If God calls us to govern this house, His plan will succeed; the impediments and opposition of men should not trouble us.” She will also write: “Divine Providence is truly admirable. God has a way of comforting those who depend on Him, no matter what happens. I place all my trust in Him!”

And Marguerite’s hope was not in vain… prominent citizens joined her in filing objections to the Ordinance. Among them were many who had put their names to the earlier document repudiating “Les Soeurs Grises.” The Sulpicians who had always supported Marguerite’s work, asked their members in France to appeal to the Royal Court and on May 12, 1752, the Ordinance of October 1750 was retracted. And in 1753, King Louis XV of France, signed the “Letters Patent” which sanctioned the appointment of Marguerite d’Youville as Directress of the General Hospital of Montreal. More importantly, the document also established, for the civil part, the new institute of the Sisters of Charity, known as the Grey Nuns. Another great joy was soon to follow these…

Indeed, Bishop de Pontbriand, although for some time an admirer of the nuns, hesitated to approve officially their Constitutions and costume: he thought the sisters were so fervent they would never need such rigid rules. But two years later, in 1755, he went along with their wishes and gave his canonical approval. That same year on August 25th, Fr. Louis Normant, co-founder of the Institute, bestowed on Mother d’Youville, who was now 54, and her companions, the religious habit – a simple grey dress and black head covering, similar to a widow’s bonnet. They also wore a silver cross with a heart in relief, at the centre. A fleur-de-lis at each corner of the cross commemorated their French origin. Because of their grey habit, the Sisters were now affectionately called: the Grey Nuns.

They were now respected by the people and were regarded as Mothers and Sisters to the poor, the elderly, orphans, and prostitutes, the mentally ill, physically handicapped, chronically ill and abandoned infants. Their work was now recognized for what it was: a mission of charity and love. In this same year, Mother d’Youville and her companions began their work as nurses during an epidemic of chicken pox. The disease also spread to the Indian missions around Montreal. Since they were not cloistered nuns, Marguerite and her companions would go into homes and take care of the sick that could not be hospitalized.

The hospital was nearly closed several times due to financial problems and armed conflict between the English and French for the region; Mother Marguerite and her sisters made clothes which were sold to traders in order to raise money, and her care for sick English soldiers caused them to avoid damage to the building. The hospital became known as the Hotel Dieu (House of God). In time, a proverb grew among the poor of Montreal and Church officials, “Go to the Grey Nuns, they never refuse to serve.” Their hospital set a standard for medical care and Christian compassion.

In 1765 a fire destroyed the hospital but nothing could destroy Marguerite’s faith and courage. She asked her sisters and the poor who lived at the hospital, to recognize the hand of God in this disaster and to offer Him praise. Marguerite knelt in the ashes of the hospital and led all there gathered in the Te Deum, a hymn to God’s Providence in all things.

At the age of 64 Marguerite undertook the reconstruction of this shelter for those in need. She fought with government officials seeking to restrain her charity. Totally exhausted from a lifetime of self-giving, Marguerite died on December 23, 1771, around 8:30pm, aged 70 years, and will always be remembered as a loving mother who served Jesus Christ in the poor.

During the autumn of 1771, Marguerite’s health began to fail, and in early December she suffered a stroke. When later she had another stroke and became paralyzed, she knew that her service to the poor would soon come to an end. She also knew that her last words would make a permanent impression on those whose lives were intertwined with her own. To her spiritual daughters, she bequeathed her great spirit of charity, recommending that they should “remain faithful to the duties of the life they have embraced… and always follow the paths of regularity, obedience, mortification, but most of all, the most perfect union should always reign among them.”

Marguerite was one woman, but this daughter of the Church had a vision of caring for the poor that has spread far and wide. Her sisters have built schools, hospitals, and orphanages and have served on almost every continent. Today, her mission is courageously carried on in a spirit of hope by the Sisters of Charity of Montreal, “Grey Nuns” and their sister communities: the Sisters of Charity of St. Hyacinthe, the Sisters of Charity at Ottawa, the Sisters of Charity of Quebec, the Grey Nuns of the Sacred Heart (Philadelphia) and the Grey Sisters of the Immaculate Conception (Pembroke). They are especially known for their work among the Eskimos.

Pope John XXIII beatified Marguerite on May 3, 1959 and called her “Mother of Universal Charity” – a well-merited title for one who continues to this day to reach out to all with love and compassion. Marguerite d’Youville can sympathize with the unfortunate and painful situation of so many orphans, with adolescents worried about the future, with disillusioned girls who live without hope, with married woman suffering from unrequited love and with single parents. But most especially, Marguerite is a kindred spirit with all who have given their lives to helping others. The power of Marguerite’s intercession before God was clearly evidenced when a young woman stricken with acute myelobastic leukemia in 1978 was miraculously cured. This great favor opened for Marguerite the door to the official proclamation of sainthood.

St Marguerite d’Youville is patroness against the death of children, for difficult marriages, for in-law problems, for loss of parents, of those opposed by Church authorities, of people ridiculed for their piety, for victims of adultery, for victims of unfaithfulness, and for widows, among other causes.

-The mortal remains of Saint Marguerite d’Youville were transferred to St. Anne de Varennes Basilica on December 9

-by Sr. Diane Beaudoin, SGM

Maison Généralice, Saint-Hyacinthe, Québec

“On December 7 – 9, 2010 we lived an extraordinary event; the transfer of the remains of St. Marguerite d’Youville from the Grey Nuns of Montreal motherhouse to St. Anne Basilica in Varennes, her place of birth.

The journey began with a Mass at the Grey Nuns’ motherhouse chapel, where the remains of St. Marguerite were ceremoniously removed from the altar and placed on a portable altar prepared for its reception. The remains were then brought to the infirmary, so that the elderly and infirmed sisters could say farewell and venerate their beloved mother and foundress. The remains were then returned to the chapel for an official sending off by Sr. Jacqueline St.-Ives, General Superior of the Grey Nuns of Montreal. With a great sense of loss, but with much gratitude and joy, the journey of transfer began. The remains were taken to a waiting hearse and with a cortege of about a dozen limousines and with police escort, St. Marguerite’s remains travelled the short distance from the motherhouse to Maison Mère d’Youville.

Here at Maison Mère d’Youville, the original General Hospital of Montréal, where St. Marguerite cared for the poor, her remains were brought to the very room where she lived and died and for the next 24 hours, we could pray, venerate her holy remains, and just be with her. It was a powerful experience.

The second day of the journey found us in procession again from Maison Mère d’Youville to Notre-Dame Basilica, for a Mass celebrated by Cardinal Jean-Claude Turcotte of Montreal. It was heart warming to see so many people who came to offer their tribute to St. Marguerite. For the people of Montreal, this was an opportunity to remember Marguerite’s life and mission and give recognition to the Grey Nuns for their continuing mission toward those most in need today.

Upon leaving the Basilica, our cortege, again with police escort, travelled to Boucherville, a city founded by Marguerite’s great-grandfather Pierre Boucher, and where her son Charles was pastor. Following an inspiring celebration where we listened to the story of Marguerite’s life, we left for our final destination, St. Anne’s Basilica in Varennes. As we entered the city we noticed a large billboard, with St. Marguerite’s picture and the words “Welcome Home.” The journey was now complete!

On the third and final day of this journey, we again celebrated a magnificent liturgy in the Basilica of St. Anne, with standing room only, presided over by the Bishop of the Diocese. At the end of the celebration, St. Marguerite’s remains were brought to their final resting place, to a tomb especially made to receive her and where for years to come we will be able to come, venerate, and pray to this Mother of Universal Charity.

Sr. Jacqueline St. Yves beautifully expressed the significance of these 3 days. “We have brought you our most prized possession, that which we hold closest to our hearts, and we trust you will take good care of her! St. Marguerite now belongs to the people, to the whole Church. There in Varennes, she awaits all who will come to her!”

http://www.hebdosregionaux.ca/monteregie/2010/12/17/sainte-marguerite-dyouville-revient-au-bercail

“St. Marguerite d’Youville has come a long way before returning to Varennes, the city where she was born there 309 years. The mortal remains of the first person to be canonized in Canada have indeed left the mother house of the Sisters of Charity of Montreal, the Grey Nuns, to be transferred to the Basilica of Sainte-Anne de Varennes on December 9, the day even the 20 th anniversary of his canonization. A Eucharistic celebration presided by Jacques Berthelet, Bishop Emeritus of the Diocese of Saint-Jean-Longueuil, highlighted the event.

The basilica filled to overflowing with the faithful here and elsewhere, the ceremony was attended by many dignitaries, including the Lieutenant Governor of Quebec, Pierre Duchesne, the bishop of the diocese elected Saint-Jean-Longueuil Lionel Gendron, bishops colleagues from Canada and abroad and representatives of the Grey Nuns. “You know Varennes is rich with the legacy of its history and its religious heritage. We owe much of our development to the builders that were clergymen and all the parish staff, “said Mayor of Varennes, Martin Damphousse, at a cocktail reception prior to the celebration.

A choir of forty people, accompanied by a violin and an organ, scored Mass grandiose songs and a procession opened and closed the ceremony. Bouquets of daisies were placed here and there. Like Marguerite d’Youville, the remains were contained in a simple wooden box, placed in the middle of the aisle.

Claude Lafortune, former host of The Gospel of paper , and a member of sacred art committee of the diocese, described the chapel, located in the transept of the basilica, which was to house the tomb of the holy woman.The tomb granite is decorated with a bouquet of daisies in bronze. A processional cross similar to that worn by Marguerite d’Youville, with lily flowers at the ends and the Sacred Heart, was forged. The statue of the saint, already in the basilica, was placed beside the grave.

The mass was of an international character occurring in French and English. A prayer inspired by the life of the one we called Mother of Universal Charity has even been made in several languages, including French, English, Spanish and Portuguese. “The mission of the church is to shine here and elsewhere. The deeper meaning of this passage of the mortal remains of St. Marguerite d’Youville of the parent company Grey Nuns at the Basilica is the return to God’s people. We must go to the people in whom Christ is present, “said Bishop Berthelet.

At the end of the celebration, the Sisters Grey handed the key to the tomb of “this flower a heart of gold,” as it is called Sister Jacqueline St-Yves, superior general of the Grey Nuns of Montreal, Raymond Fish, pastor the Sainte-Anne Basilica in Varennes. Then, the documents authenticating the translation of the remains were signed and deposited in the tomb with the remains of Saint Marguerite d’Youville. This is the first time in North America that a saint is buried in a place of worship.

“The first result of this translation is that the life and work of Marguerite d’Youville does not lapse with the Congregation of the Sisters of Charity. Her memory will live on in a more vibrant place thanks to the prayers, “says Fish. Visitors will get to Sainte-Anne Basilica in Varennes throughout the year to pray at the tomb of the holy woman.

http://www.hannasheartsofhope.org/media/SaintMargueriteDYouville.pdf

“All the wealth in the world cannot be compared with the happiness of living together happily united.” -St Margaret d’Youville

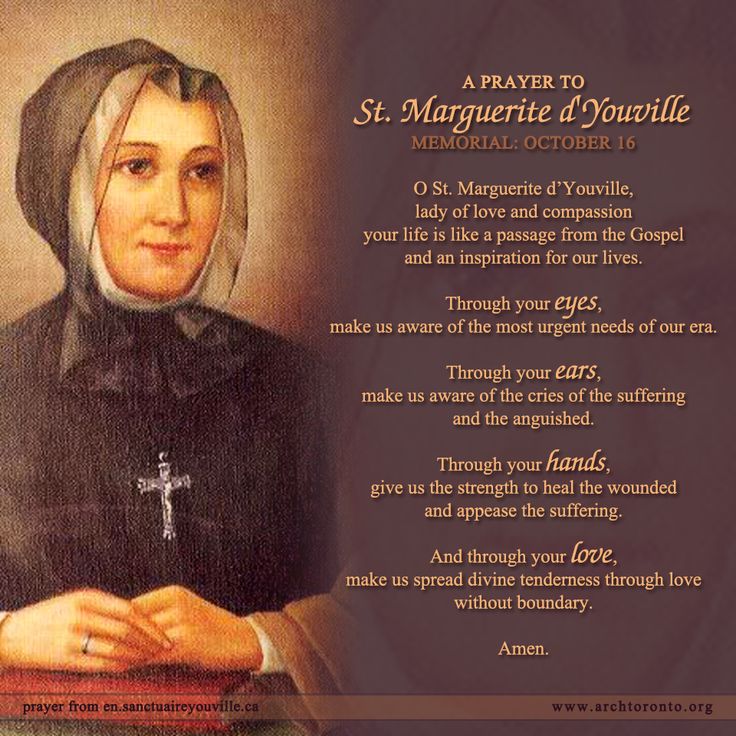

Prayer to St Marguerite d’Youville

St. Marguerite d’Youville,

During your lifetime, you opened your heart and home

to every type of human misery.

Listen now to my prayer of petition.

I count on you to plead with the God of Love

to grant the favor I seek with confidence and trust.

Gift us as you were gifted; with ever deepening faith,

with firm hope and trust.

Let my life be for all a service of love.

Mother of Universal Charity,

your love for the poor made the impossible possible.

Please make haste to help me.

Amen.

Love,

Matthew