Anna Ivanovna Abrikosova (Russian: Анна Ивановна Абрикосова; 23 January 1882 – 23 July 1936), later known as Mother Catherine of Siena, O.P. (Russian: Екатери́на Сие́нская or Ekaterina Sienskaya), was a Russian Greek-Catholic religious sister, literary translator, and victim of Joseph Stalin’s concentration camps. She was also the foundress of a Byzantine Catholic community of the Third Order of St. Dominic. She has gained wide attention, even among secular historians of Soviet repression. In an anthology of women’s memoirs from the GULAG, historian Veronica Shapovalova describes Anna Abrikosova as, “a woman of remarkable erudition and strength of will”, who, “managed to organize the sisters in such a way that even after their arrest they continued their work.” She is also mentioned by name in the first volume of The Gulag Archipelago by Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

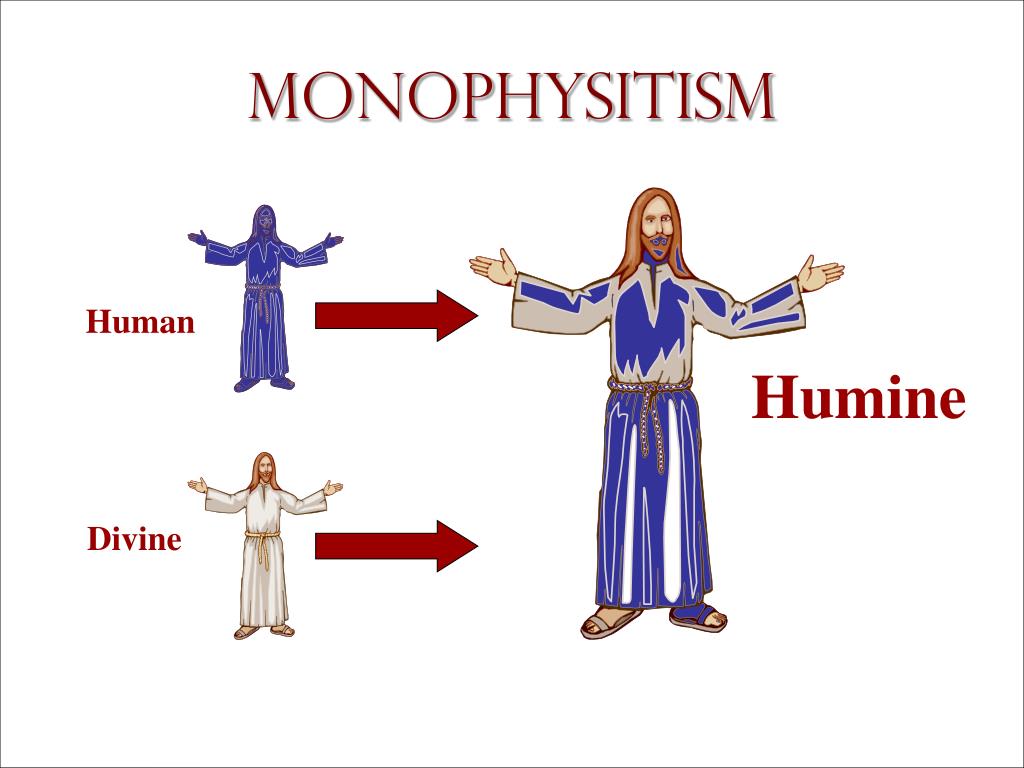

The Russian Greek Catholic Church (Russian: Российская греко-католическая церковь, Rossiyskaya greko-katolicheskaya tserkov; Latin: Ecclesiae Graecae Catholico Russica), Russian Byzantine Catholic Church or simply Russian Catholic Church, is a sui iuris Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic jurisdiction of the worldwide Catholic Church. Historically, it represents the first reunion of members of the Russian Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church. It is now in full communion with and subject to the authority of the Pope of Rome as defined by Eastern canon law.

Russian Catholics historically had their own episcopal hierarchy in the Russian Catholic Apostolic Exarchate of Russia and the Russian Catholic Apostolic Exarchate of Harbin, China. However, these offices are currently vacant. Their few parishes are served by priests ordained in other the Eastern Catholic Churches, former Eastern Orthodox priests, and Roman Catholic priests with bi-ritual faculties. The Russian Greek Catholic Church is currently led by Bishop Joseph Werth as Ordinary.

Early life

Anna Ivanovna Abrikosova was born on 23 January 1882 in Kitaigorod, Moscow, Russian Empire, into a wealthy family of factory owners and philanthropists, who were the official suppliers of chocolate confections to the Russian Imperial Court. Her grandfather was the industrialist Aleksei Ivanovich Abrikosov. Her father, Ivan Alekseievich Abrikosov, was expected to take over the family firm until his premature death from tuberculosis. Her brothers included Tsarist diplomat Dmitrii Abrikosov and Alexei Ivanovich Abrikosov, the doctor who embalmed Vladimir Lenin.

Although the younger members of the family rarely attended Divine Liturgy, the Abrikosovs regarded themselves as pillars of the Russian Orthodox Church. Anna’s parents died early: her mother while giving birth to her, and her father ten days later, of tuberculosis. Anna and her four brothers were raised in the house and provincial estate of her uncle, Nikolai Alekseevich Abrikosov.

The memoirs of her brother Dmitrii “describes their childhood as carefree and joyous” and writes that their British governess “was quite shocked at the close relationship between parents and children.” She used to say that in England, “children were seen and not heard.”

Desiring to be a teacher, Anna graduated with Gold Medal Grade from the First Women’s Lyceum in Moscow in 1899. She then entered a teacher’s college, where the student body ostracized and bullied her for being from a wealthy family.

She later recalled, “Every day as I went into the room the girls would divide up the passage and stand aside not to brush me as I passed because they hated me as one of the privileged class.”

After graduating, she briefly taught at a Russian Orthodox parochial school but was forced to leave after the priest threatened to denounce her to the Okhrana for teaching the students that Hell does not exist. Although heartbroken Anna then decided to pursue an old dream of attending Girton College, the all-girls adjunct to Cambridge University. While studying history from 1901-1903, Anna befriended Lady Dorothy Georgiana Howard, the daughter of the 9th Earl and “Radical Countess” of Carlisle. Lady Dorothy’s letters to her mother remain the best source for Anna’s college days. She ultimately returned to Russia without a degree and married her first cousin, Vladimir Abrikosov.

Catholicism

The Abrikosovs spent the next decade traveling in the Kingdom of Italy, Switzerland and France.

According to Father Cyril Korolevsky:

“While traveling, she studied a great deal. She… read a number of Catholic books. She particularly liked the Dialogue of Saint Catherine of Siena and began to doubt official Orthodoxy more and more. Finally, she approached the parish priest of the large, aristocratic Church of the Madeleine in Paris, Abbé Maurice Rivière, who later became Bishop of Périgueux. He instructed and received her into the Catholic Church on 20 December 1908. Amazingly, especially at that time, he informed her that even though she had been received with the Latin Ritual, she would always canonically belong to the Greek-Catholic Church. She went on reading and came to prefer the Dominican spirituality and to enjoy Lacordaire’s biography of Saint Dominic… She never stopped thinking of Russia, but like many other people, she thought that only the Roman Catholic priests were able to work with Russian souls. Little by little, she won her husband over to her religious convictions. On 21 December 1909, Vladimir was also received into the Catholic Church. They both thought they would stay abroad, where they had full freedom of religion and… a vague plan to join some monastery or semi-monastic community. Since they knew that according to the canons they were Greek-Catholics, they petitioned Pius X through a Roman prelate for permission to become Roman Catholics — they considered this a mere formality. To their great surprise the Pope refused outright… and reminded them of the provisions of Orientalium dignitas. They had just received this answer when a telegram summoned them to Moscow for family reasons.”

The couple returned to Russia in 1910. Upon their return, the Abrikosovs found a group of Dominican tertiaries which had been established earlier by one Natalia Rozanova. They were received into the Third Order of St. Dominic by Friar Albert Libercier, O.P., of the Roman Catholic Church of St. Louis in Moscow. On 19 May 1917, Vladimir was ordained to the priesthood by Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. With her husband now a priest, according to Catholic custom, Anna was free to take monastic vows. She took vows as a Dominican Sister, assuming her religious name at that time, and founded a Greek-Catholic religious congregation of the Order there in Moscow. Several of the women among the secular tertiaries joined her in this commitment. Thus was a community of the Dominican Third Order Regular established in Soviet Russia.

Persecution

During the aftermath of the October Revolution, the convent was put under surveillance by the Soviet secret police.

In 1922, Father Vladimir Abrikosov was exiled to the West aboard the Philosopher’s Ship. Soon after, Mother Catherine wrote him a letter from Moscow, “I am, in the fullest sense of the word, alone with half naked children, with sisters who are wearing themselves out, with a youthful, wonderful, saintly but terribly young priest, Father Nikolai Alexandrov, who himself needs support, and with parishioners dismayed and bewildered, while I myself am waiting to be arrested, because when they searched here, they took away our Constitution and our rules.”

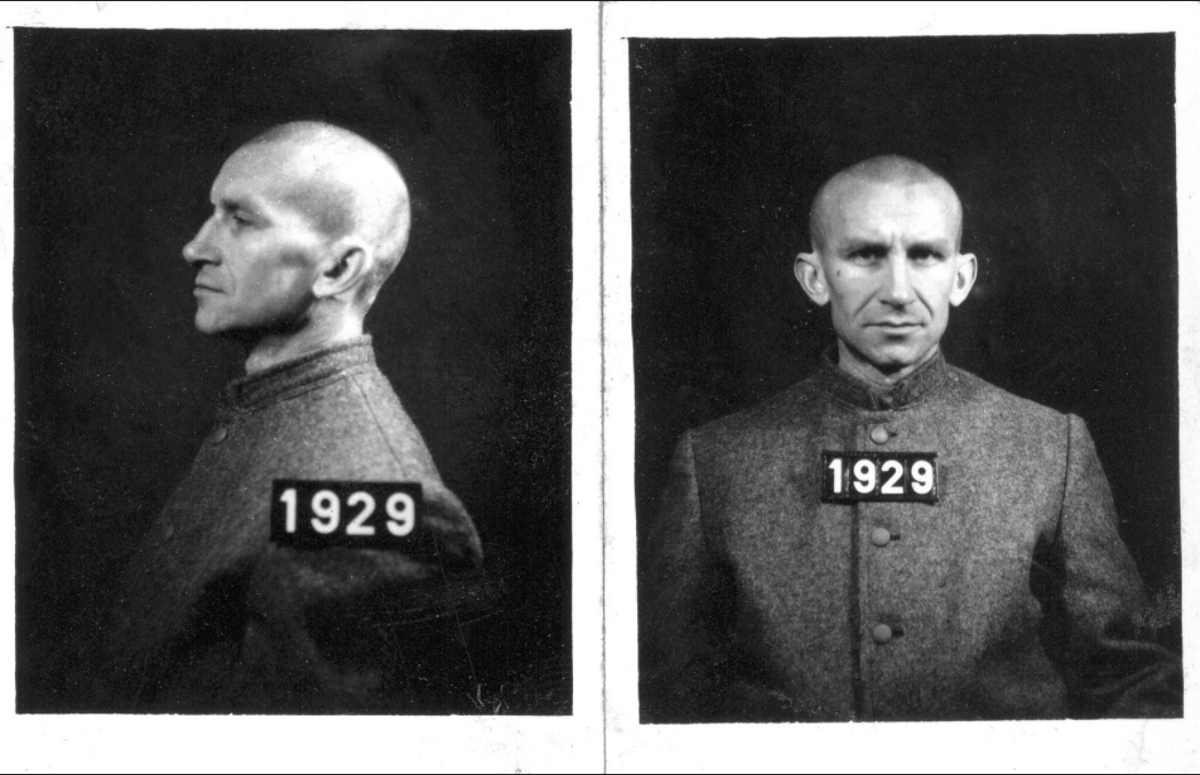

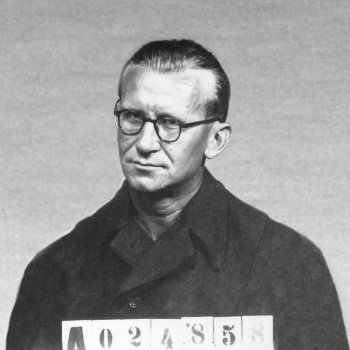

Imprisonment

Due to her work with the Papal Aid Mission to Russia, Mother Catherine was arrested by the OGPU. Shortly before the Supreme Collegium of the OGPU handed down sentences, Mother Catherine told the sisters of her community, “Probably every one of you, having given your love to God and following in His way, has in your heart more than once asked Christ to grant you the opportunity to share in His sufferings. And so it is; the moment has now arrived. Your desire to suffer for His sake is now being fulfilled.”[13]

Mother Catherine was sentenced to ten years of solitary confinement and imprisoned at Yaroslavl from 1924 to 1932. After being was diagnosed with breast cancer, she was transferred to Butyrka Prison infirmary for an operation in May 1932. The operation removed her left breast, part of the muscles on her back and side. She was left unable to use her left arm, but was deemed cancer free.[14]

Release

Meanwhile, Ekaterina Peshkova, the wife of author Maxim Gorky and head of the Political Red Cross, had interceded with Stalin to secure her release and grounds of her illness and that her sentence was almost complete.

On August 13, 1932, Mother Catherine petitioned to be returned to Yaroslavl. Instead, she was told that she could leave any time she wanted. On August 14, she walked free from Butyrka and went directly to the Church of St. Louis des Français.[15]

Bishop Pie Neveu, who had been secretly consecrated as an underground Bishop in 1926,[16] wrote to Rome after meeting her, “This woman is a genuine preacher of the Faith and very courageous. One feels insignificant beside someone of this moral stature. She still cannot see well, and she can only use her right hand, since the left is paralyzed.”[17]

Despite warnings that it could lead to another arrest, Mother Catherine also reestablished ties to the surviving Sisters. She later told interrogators, “After my release from the isolator and happening to be in Moscow, I renewed my links with a group of people whom an OGPU Collegium had condemned in 1923. In reestablishing contact with them, my purpose was to assess their political and spiritual condition after their arrest, administrative exile and the expiration of their residence restriction. Following my meetings with them, I became convinced that they retained their earlier world outlook.”[18]

Rearrest

After immediately entering communication with the surviving Sisters of the congregation, Mother Catherine was arrested, along with 24 other Catholics, in August 1933. In what the NKVD called “The Case of the Counterrevolutionary Terrorist-Monarchist Organization”, Mother Catherine stood accused of plotting to assassinate Joseph Stalin, overthrow the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and restore the House of Romanov as a constitutional monarchy in concert with “international fascism” and “Papal theocracy”. It was further alleged that the organization planned for the restoration of Capitalism and for collective farms to be broken up and returned to their former owners among the Russian nobility and the kulaks. The NKVD alleged that the organization was directed by Pope Pius XI, Bishop Pie Neveu, and the Vatican’s Congregation for Eastern Churches.[19] After being declared guilty as charged, Mother Catherine was returned to the Political Isolator Prison at Yaroslavl.

Death

Abrikosova died of bone cancer at Butyrka Prison infirmary on July 23, 1936, at the age of 54 years. After being autopsied, her body was secretly cremated at the Donskoy Cemetery and her ashes were buried in a mass grave at the same location.

“I wish to lead a uniquely supernatural life and to accomplish to the end my vow of immolation for the priests and for Russia.”

“Soviet youth cannot talk about its world outlook; it is blinkered. It is developing too one-sidedly, because it knows only the jargon of Marxist-Leninism.”

“A political and spiritual outlook should develop only on the basis of a free critical exploration of all the facets of philosophical and political thought.”

Prayer for the beatification of the Servant of God Mother Catherine (Abrikosova)

O God Almighty, Your Son suffered on the Cross and died for the salvation of people.

Imitating Him, Your Servant Mother Catherine (Abrikosova) loved You from the bottom of her heart, served You faithfully during the persecutions and devoted her life to the Church. Make her famous in the assembly of Your blessed, so that the example of her faithfulness and love would shine before the whole world. I pray to You through her intercession, hear my request………………………………..through Christ our Lord. Amen.

The prayer has to be used in private, as well as in public, out of the Holy Mass.

+ Archbishop Thaddeus Kondrusiewich, St. Petersburg 05.04.2004

Postulator asks to inform about the graces received through the mediation of the Servant of God.

Address: Fr. Bronislav Chaplicki, 1st Krasnoarmyskaya, D. 11, 198005, St. Petersburg, Russia

Love, pray for me,

Matthew