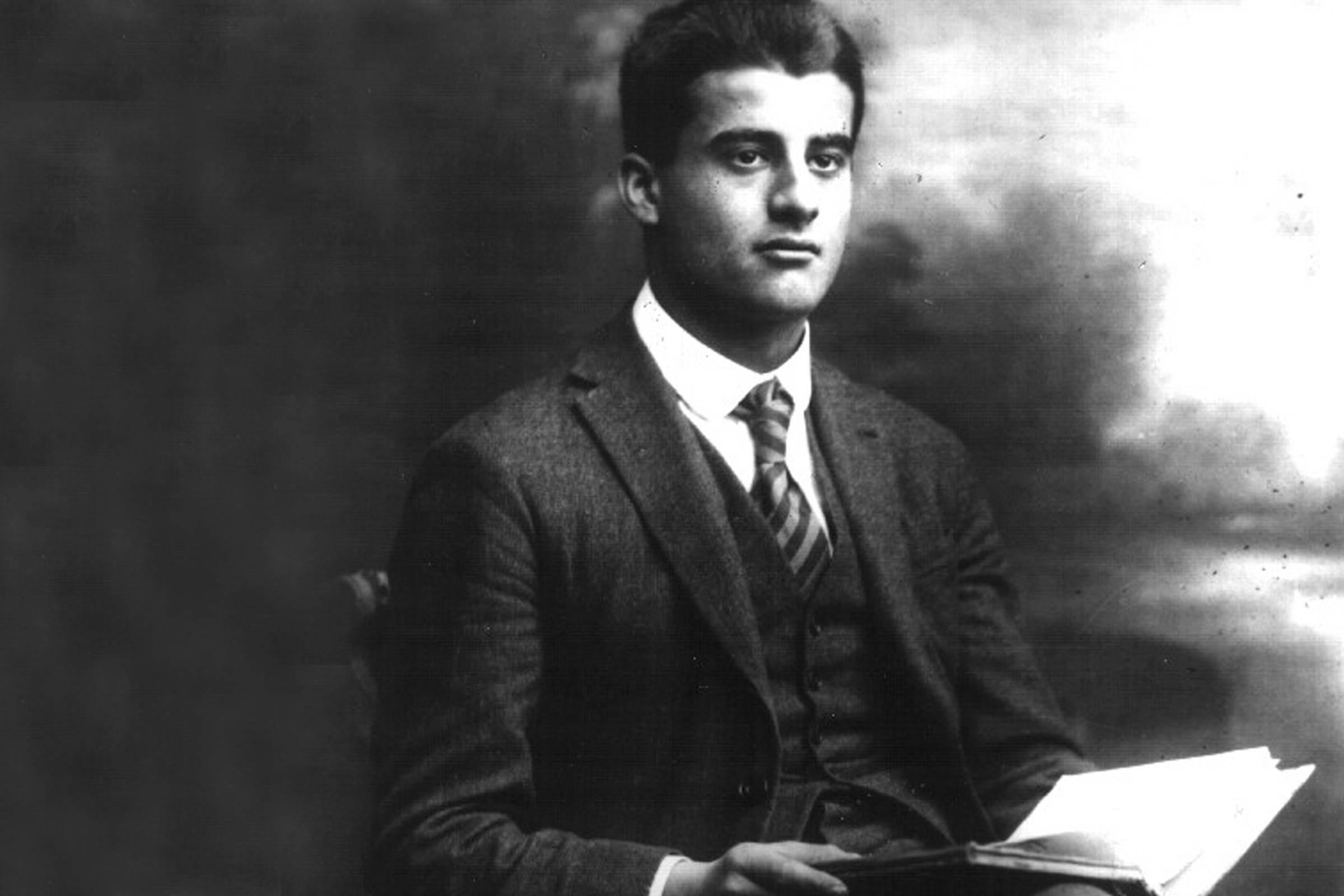

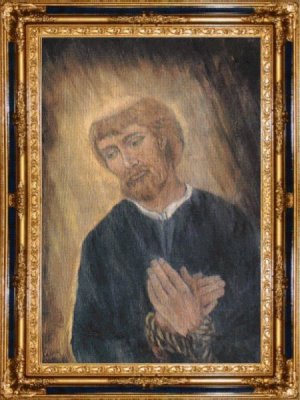

-by St Andrew by Artus Wolffort, first half of the 17th century, oil on canvas, private collection.

Andrew the Apostle (Greek: Ἀνδρέας, Andreas; from the early 1st century – mid to late 1st century AD), also known as Saint Andrew and called in the Orthodox tradition Prōtoklētos (Πρωτόκλητος) or the First-called, was a Christian Apostle and the brother of Saint Peter.

The name “Andrew” (Greek: manly, brave, from ἀνδρεία, Andreia, “manhood, valour”), like other Greek names, appears to have been common among the Jews, Christians, and other Hellenized people of Judea. No Hebrew or Aramaic name is recorded for him. According to Orthodox tradition, the apostolic successor to Saint Andrew is the Patriarch of Constantinople.

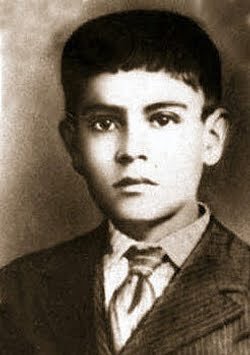

The New Testament states that Andrew was the younger brother of Simon Peter, and likewise a son of John, or Jonah. He was born in the village of Bethsaida on the Sea of Galilee. Both he and his brother Peter were fishermen by trade, hence the tradition that Jesus called them to be His disciples by saying that he will make them “fishers of men” (Greek: ἁλιεῖς ἀνθρώπων, halieis anthrōpōn). At the beginning of Jesus’ public life, they were said to have occupied the same house at Capernaum.

Acts/gospel of Andrew

The apocryphal Acts of Andrew, mentioned by Eusebius, Epiphanius and others, is among a disparate group of Acts of the Apostles that were traditionally attributed to Leucius Charinus. “These Acts (…) belong to the third century: ca. A.D. 260,”, and are therefore apocryphal, in the opinion of M. R. James, who edited them in 1924. The Acts, as well as a Gospel of St Andrew, appear among rejected books in the Decretum Gelasianum connected with the name of Pope Gelasius I (d. 496 AD).

After the Resurrection

After Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, St. Andrew the Apostle preached the gospel in Asia Minor and in Scythia as far as Kiev, all around the Black Sea, including Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus, where my paternal grandmother was born.

Saint Andrew was martyred by crucifixion at Patras in Achaea in Greece. Because St. Andrew deemed himself unworthy to be crucified on the same type of cross on which Christ had been crucified, he was tied, instead of nailed, to a Crux decussata, as saltire, or X shaped cross, ostensibly so that he would suffer longer. The Apostle Andrew did not die right away but instead he was left to suffer for two days while he continued to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ until he finally expired.

Relics

-St Andrew’s Cathedral in Patras

Originally, the saint’s remains were preserved in Patras. Through the centuries of Christianity, and many wars and conquests, what remains of the saint’s relics are a small finger, the top of his cranium and pieces of the cross on which he was crucified. These are kept in a shrine at the Church of St. Andrew in Patras. Shortly after St Andrew’s death, most of his relics were translated from Patras to Constantinople by order of the Roman Emperor Constantius II around 357 AD and deposited in the Church of the Holy Apostles.

There are legends about how other relics of St Andrew reached the British isles, including a kneecap, an upper arm bone, three fingers and a tooth. Most likely, the relics were probably brought to Britain in 597 AD as part of the Augustine Mission, and then in 732 to Fife, Scotland by Bishop Acca of Hexham, a well-known collector of religious relics.

The skull of St. Andrew, which had been taken to Constantinople, was returned to Patras by Emperor Basil I, who ruled from 867 to 886.

In 1208, following the sack of Constantinople, those relics of St. Andrew and St. Peter which remained in the imperial city were taken to Amalfi, Italy, by Cardinal Peter of Capua, a native of Amalfi. A cathedral (Duomo), was built, dedicated to St. Andrew (as is the town itself), to house a tomb in its crypt where it is maintained that most of the relics of the apostle, including an occipital bone, remain.

Thomas Palaeologus was the youngest surviving son of Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos. Thomas ruled the province of Morea, the medieval name for the Peloponnese. In 1461, when the Ottomans crossed the Strait of Corinth, Palaeologus fled Patras for exile in Italy, bringing with him what was purported to be the skull of St. Andrew. He gave the head to Pope Pius II, who had it enshrined in one of the four central piers of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

In September 1964, Pope Paul VI, as a gesture of goodwill toward the Greek Orthodox Church, ordered that all of the relics of St. Andrew that were in Vatican City be sent back to Patras. Cardinal Augustin Bea along with many other cardinals presented the skull to Bishop Constantine of Patras on 24 September 1964.

The cross of St. Andrew was taken from Greece during the Crusades by the Duke of Burgundy. It was kept in the church of St. Victor in Marseilles until it returned to Patras on 19 January 1980. The cross of the apostle was presented to the Bishop of Patras Nicodemus by a Catholic delegation led by Cardinal Roger Etchegaray. All the relics, which consist of the small finger, the skull (part of the top of the cranium of Saint Andrew), and the cross on which he was martyred, have been kept in the Church of St. Andrew at Patras in a special shrine and are revered in a special ceremony every 30 November, his feast day.

In 2006, the Catholic Church, again through Cardinal Etchegaray, gave the Greek Orthodox Church another relic of St. Andrew.

Scotland?

-Crucifixion of St. Andrew, by Juan Correa de Vivar (1540 – 1545), University of St Andrew’s Special Collection

In Scottish Gaelic, St Andrew’s name is rendered ‘Là Naomh Anndrais’. St Andrew’s links with Scotland come from the Pictish King Oengus I, who built a monastery in what is now the town of St Andrews – where the Scottish university now stands – after the relics of the saint were brought to the town in the eighth century.

But he was made the patron saint of Scotland after the king’s descendant, Oengus II, prayed to St. Andrew on the eve of a crucial battle against English warriors from Northumberland, around 20 miles east of Edinburgh.

Legend has it that, heavily outnumbered, Oengus II told St. Andrew that he would become the patron saint of Scotland if he were granted victory. On the day of the battle, clouds are said to have formed a saltire in the sky, and Oengus’s army of Picts and Scots were victorious.

St Andrew’s was a popular medieval pilgrimage site up until the 16th century – where the supposed remains of the saint including a tooth, kneecap, arm and finger bone were kept.

In 1870, the Archbishop of Amalfi sent an apparent piece of the saint’s shoulder blade to Scotland, where it has since been stored in St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh. The other relics were destroyed in the Scottish Reformation.

The Saltire flag – a white cross on a blue background – is said to have come from this divine intervention and has been used to represent Scotland since 1385.

-statue of Andrew in the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran, Rome, by Camillo Rusconi.

“In the face of gender theory and feminist ideologies which challenge the notion of manhood, the Church needs real men. We need to respond to the Biblical command viriliter agite found frequently in the Vulgate. The phrase translates as “act like a man” in one form or another in Scripture (1 Cor 16:13, Dt 31:6, Ps 30(31):25, 2 Chr 32:7, 1 Mac 2:64). One man who obeyed was St. Andrew, and his very name suggests it. St. Thomas Aquinas explains, “Andrew is interpreted ‘manly’; for as in Latin, ‘virilis‘ [“manly”] is derived from ‘vir’ [man], so in Greek, Andrew is derived from ανηρ [anēr: man]. Rightly is he called manly, who left all and followed Christ, and manfully persevered in His commands.”

Commenting on St. Andrew, St. Thomas gives us 5 tips on how to viriliter agite.

Obey Promptly: “Aristotle states, ‘Those who are moved by God do not need to be counselled; for they have a principle surpassing counsel and understanding.’ St. Chrysostom pronounces the following eulogium of them: ‘They were in the midst of their business; but, at His bidding, they made no delay, they did not return home saying: let us consult our friends, but, leaving all things, they followed, Him, as Elisha followed Elijah.’ Christ requires of us a similar unhesitating and instant obedience.”

Build Up: “And so Andrew, being now perfectly converted, does not keep the treasure he found to himself, but hurries and quickly runs to his brother to share with him the good things he has received. And so, the first thing Andrew did was to look for his brother Simon, so that they might be related in both blood and faith: “A brother that is helped by his brother is like a strong city” (Prv 18:19); ‘Let him who hears say, ‘Come’ (Rv 22:17).”

Hunt Souls: “This gives us the situation of the disciples he called: for they were from Bethsaida. And this is appropriate to this mystery. For ‘Bethsaida’ means ‘house of hunters,’ to show the attitude of Philip, Peter and Andrew at that time, and because it was fitting to call, from the house of hunters, hunters who were to capture souls for life: ‘I will send my hunters’ (Jer 16:16).”

Preach with Courage: “Every preacher should have those names, ‘Peter’ and ‘Andrew.’ For ‘Simon’ means obedient, ‘Peter’ means comprehending, and ‘Andrew’ means courage. For a preacher should be obedient, that he might invite others to it: ‘The obedient man shall speak of victories’ (Pr 21:28). He should comprehend, that he may know how to instruct others: ‘I had rather speak five words with my mind, in order to instruct others’ (1 Cor 14:19). He should be courageous in order to face threats: ‘I make you this day a fortified city, an iron pillar, and a bronze wall’ (Jer 1:18); ‘I have made your face hard against their faces, and your forehead hard against their foreheads. Like adamant harder than flint I have made your face’ (Ez 3:8).”

Commit: “Our Lord declared that it belongs to the perfection of life that a man follow Him, not anyhow, but in such a way as not to turn back. Wherefore He says again (Lk. 9:62): ‘No man putting his hand to the plough, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God.’ And though some of His disciples went back, yet when our Lord asked (Jn. 6:68, 69), ‘Will you also go away?’ Peter answered for the others: ‘Lord, to whom shall we go?’ Hence Augustine says (De Consensu Ev. ii, 17) that ‘as Matthew and Mark relate, Peter and Andrew followed Him after drawing their boats on to the beach, not as though they purposed to return, but as following Him at His command.’ Now this unwavering following of Christ is made fast by a vow: wherefore a vow is requisite for religious perfection.”

Glorious St. Andrew, you were the first to recognize and follow the Son of God. With your friend, St. John, you remained with Jesus, for your entire life, and now throughout eternity. Just as you led your brother, St Peter, to Christ and many others after him, draw us also to Him. Teach us how to lead them, solely out of love for Jesus and dedication to His service. Help us to learn the lesson of the Cross and carry our daily crosses without complaint, so that they may carry us to God the Almighty Father. Amen.

Love & courage,

Matthew