Mortal, you are living in the midst of a rebellious

house, who have eyes to see but do not see, who have

ears to hear but do not hear.

—Ezek. 12:2

Jesus said to [the disciples] . . . “Do you have eyes, and

fail to see? Do you have ears, and fail to hear?”

—Mk 8:17–18

“Both Jesus and Ezekiel recognized the parallel between having ears to hear and eyes to see, but in the Protestant tradition of my childhood, the emphasis was always on having ears to hear (the words of the Bible) to the loss of eyes to see. My earliest spiritual formation focused on the hearing part and omitted what became apparent later as effective avenues for engaging the seeing part. Symbolic images within worship began to inform my spirituality only when I chose the Episcopal Church as a teenager. I do not know if an increasing awareness of symbolism was due to natural maturation or to the richness of symbolic images so available in Episcopal liturgy. However, I vividly remember saying at age seventeen that my reason for converting was, in part, because my previous church was just “so plain.” As with many other seekers, I had a hunger for something more tangible. There was the longing to see God and live…

…icons provide a vehicle for our participation in God’s redemptive work. Icons are no less than the “dynamic manifestations of man’s spiritual power to redeem creation through beauty and art.”

If this were a book about icons simply as religious art, it would not be worth writing, let alone publishing. If Orthodox Christianity did not claim icons are essential for seeing the holy, I would not be motivated to try to inform non-Orthodox Christians about icons. God embodied, in the human and historical reality of Jesus of Nazareth—who is, for all Christians, also the Christ—the mystery and doctrine on which salvation depends. But finding Jesus incarnate in today’s world is the struggle of faith for many, me included. The words and images I encounter every day need to be countered, challenged, and balanced against words and images whose purposes are edifying, redemptive, and healing. ”

-Green, Mary E., (2014), Introduction, Eyes to See: The Redemptive Purpose of Icons, Morehouse Publishing, New York

Icons, to the believer, and properly understood, are incarnational, just like Christmas. Acheiropoieta, are icons not made by human hands.

In cinema involving Russian characters, you will see the Russian, typically, but it could be Greek, someone of Eastern Orthodox sentiment, cover any icon with a cloth just before performing some heinous act such as suicide. There is a reason for this.

Jesus Christ is the first eikon (alternative spelling, Greek for image) of God. Icons are a symbolic and allegorical composition of: “Behold, the eyes of the Lord are on those who fear Him, on those who hope in His mercy.” (Ps 32:18). Christian tradition dating from the 8th century identifies Luke the Evangelist as the first icon painter. There is a Christian legend that Pilate made an image of Christ.

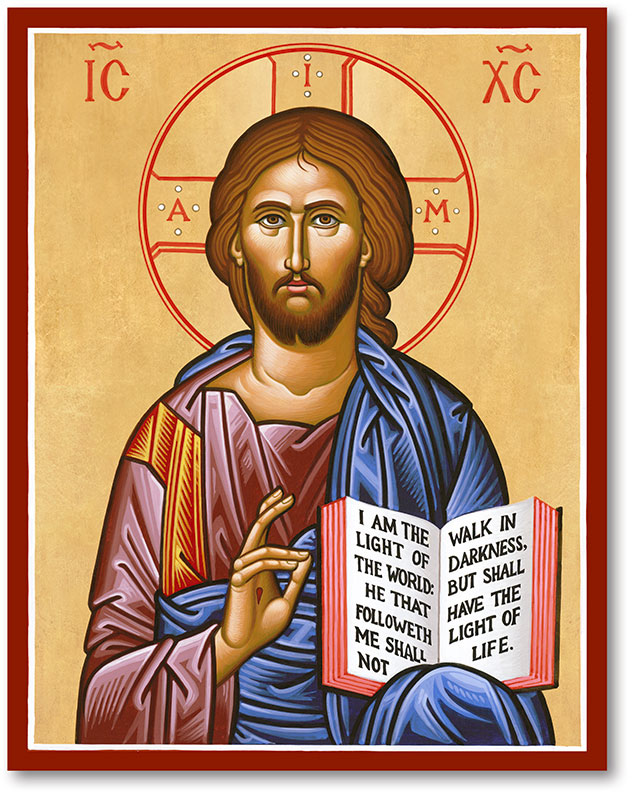

In the icons of Eastern Orthodoxy, and of the Early Medieval West, very little room is made for artistic license. Almost everything within the image has a symbolic aspect. Christ, the saints, and the angels all have halos. Angels (and often John the Baptist) have wings because they are messengers. Figures have consistent facial appearances, hold attributes personal to them, and use a few conventional poses.

Color plays an important role as well. Gold represents the radiance of Heaven; red, divine life. Blue is the color of human life, white is the Uncreated Light of God, only used for resurrection and transfiguration of Christ. If you look at icons of Jesus and Mary: Jesus wears red undergarment with a blue outer garment (God become Human) and Mary wears a blue undergarment with a red overgarment (human was granted gifts by God), thus the doctrine of deification is conveyed by icons. Letters are symbols too. Most icons incorporate some calligraphic text naming the person or event depicted. Even this is often presented in a stylized manner.

In the Eastern Orthodoxy, there are reports of particular, Wonderworking icons that exude myrrh (fragrant, healing oil), or perform miracles upon petition by believers. When such reports are verified by the Orthodox hierarchy, they are understood as miracles performed by God through the prayers of the saint, rather than being magical properties of the painted wood itself. Theologically, all icons are considered to be sacred, and are miraculous by nature, being a means of spiritual communion between the heavenly and earthly realms. However, it is not uncommon for specific icons to be characterized as “miracle-working”, meaning that God has chosen to glorify them by working miracles through them. Such icons are often given particular names (especially those of the Virgin Mary), and even taken from city to city where believers gather to venerate them and pray before them.

In the Book of Numbers it is written that God told Moses to make a bronze serpent, Nehushtan, and hold it up, so that anyone looking at the snake would be healed of their snakebites. In John 3, Jesus refers to the same serpent, saying that He must be lifted up in the same way that the serpent was. John of Damascus also regarded the brazen serpent as an icon. Further, Jesus Christ himself is called the “image of the invisible God” in Colossians 1:15, and is therefore in one sense an icon. As people are also made in God’s images, people are also considered to be living icons, and are therefore “censed” along with painted icons during Orthodox prayer services.

According to John of Damascus, anyone who tries to destroy icons “is the enemy of Christ, the Holy Mother of God and the saints, and is the defender of the Devil and his demons.” This is because the theology behind icons is closely tied to the Incarnational theology of the humanity and divinity of Jesus, so that attacks on icons typically have the effect of undermining or attacking the Incarnation of Jesus himself as elucidated in the Ecumenical Councils.

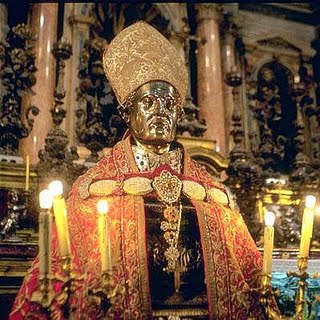

Thus to kiss an icon of Christ, in the Eastern Orthodox view, is to show love towards Christ Jesus Himself, not mere wood and paint making up the physical substance of the icon. Worship of the icon as somehow entirely separate from its prototype is expressly forbidden by the Seventh Ecumenical Council. Catholics traditionally have also favored images in the form of three-dimensional statuary, whereas in the East, statuary is much less widely employed.

Icons are often illuminated with a candle or jar of oil with a wick. (Beeswax for candles and olive oil for oil lamps are preferred because they burn very cleanly, although other materials are sometimes used.) The illumination of religious images with lamps or candles is an ancient practice pre-dating Christianity.

Windows to Heaven

Icons look different to us because they are meant to be heaven looking at us, not us at heaven, hence the Eastern Orthodox covering the icon before some unholy act, which the character does not want Heaven to see.

The eyes of an icon are meant to look into the viewer — with what has been called inverse perspective. Most Western artwork has a vanishing perspective point that draws the viewer into the painting. With an icon, the icon seems to move toward the viewer, bringing Heaven close. If you pray with an icon properly, it will seem as if heaven were drawing into you. As Franciscan Fr. Michael Scanlon wrote, “For Eastern Christians, the icon is a representation of the living God, and by coming into its presence it becomes a personal encounter with the sacred, through the grace of the Holy Spirit.”

An icon, which we would most likely refer to as a painting, the correct verb for creation is “writing an icon”. An iconographer must be prepared for this work and receive permission from the bishop or abbot to begin an icon. He or she must spiritually prepare to write an icon with prayer and fasting. As the great modern Byzantine iconographer Photios Kontoglou wrote, “The art of the icon painter is above all a sacred activity…Its style is entirely different from that of all the schools of secular painting. It does not have its aim to reproduce a saint or an incident from the Gospels, but to express them mystically, to impart to them a spiritual character…to represent the saint as he is in the heavenly kingdom, as he is in eternity.”

-by Br Cornelius Avaritt, OP

“Icons are a gift of the Church. They are beautiful images that represent Christ and the mysteries of his life. The Catechism of the Catholic Church says the following regarding icons:

The sacred image, the liturgical icon, principally represents Christ. It cannot represent the invisible and incomprehensible God, but the incarnation of the son of God has ushered in a new “economy” of images. Christian iconography expresses in images the same Gospel message that Scripture communicates by words. Image and word illuminate each other. All the signs in the liturgical celebrations are related to Christ: as are sacred images of the holy Mother of God and of the saints as well. They truly signify Christ, who is glorified in them. (CCC 1159-1161)

Praying with icons allows us to behold the face of Christ, and to catch a glimpse of his love for the world while meditating on his humanity. The representation of Christ’s humanity through an image allows us to understand more fully the gospel message and to grow in knowledge of him. Just as the sacred words of Scripture signify the events of Christ’s life, so do the images reveal a glimpse of God’s plan of salvation for the world through depictions of the life of Christ. Because the Son of God was made incarnate, he became depictable. Icons depict his humanity, and we can pray with icons to deepen our love for Christ.

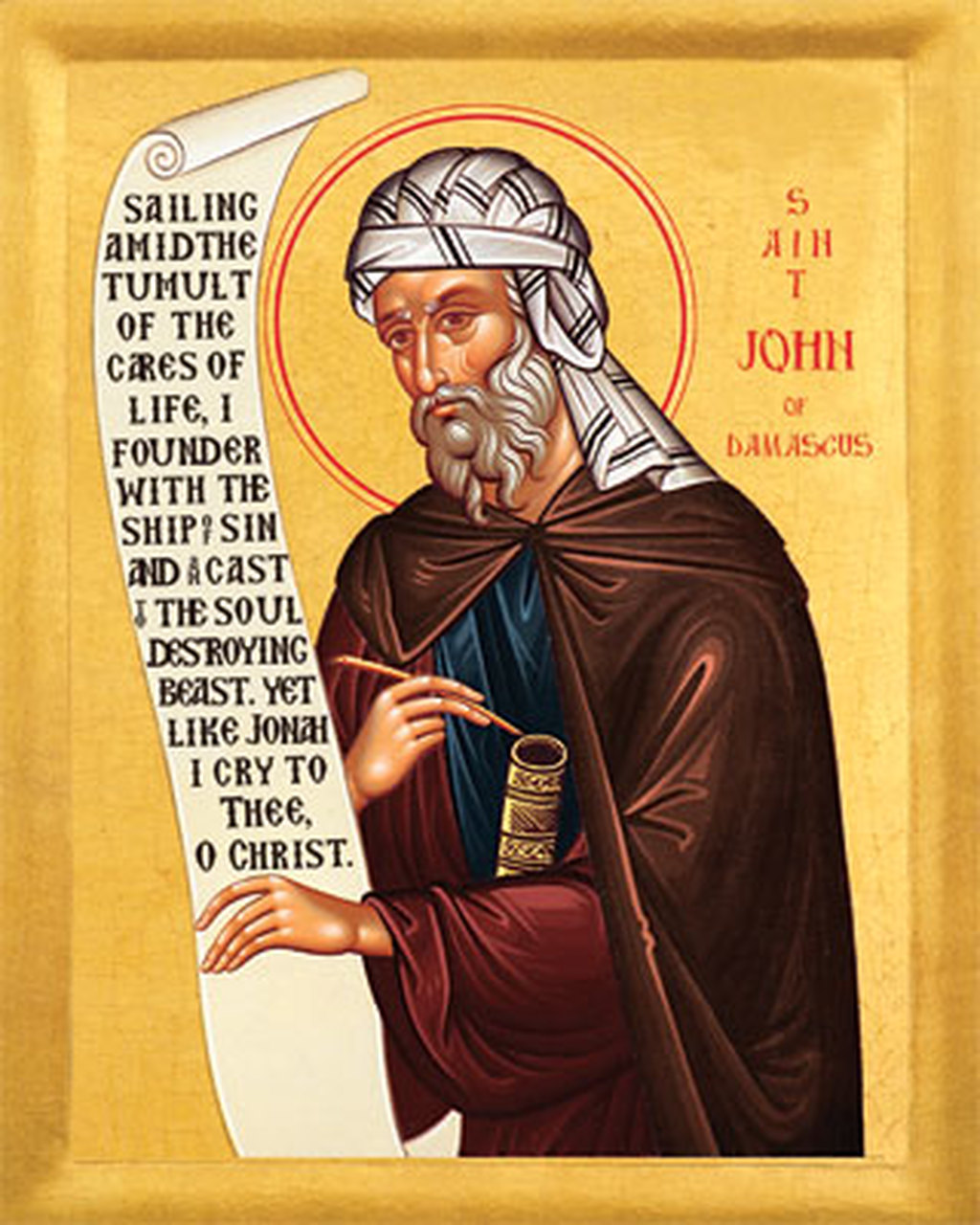

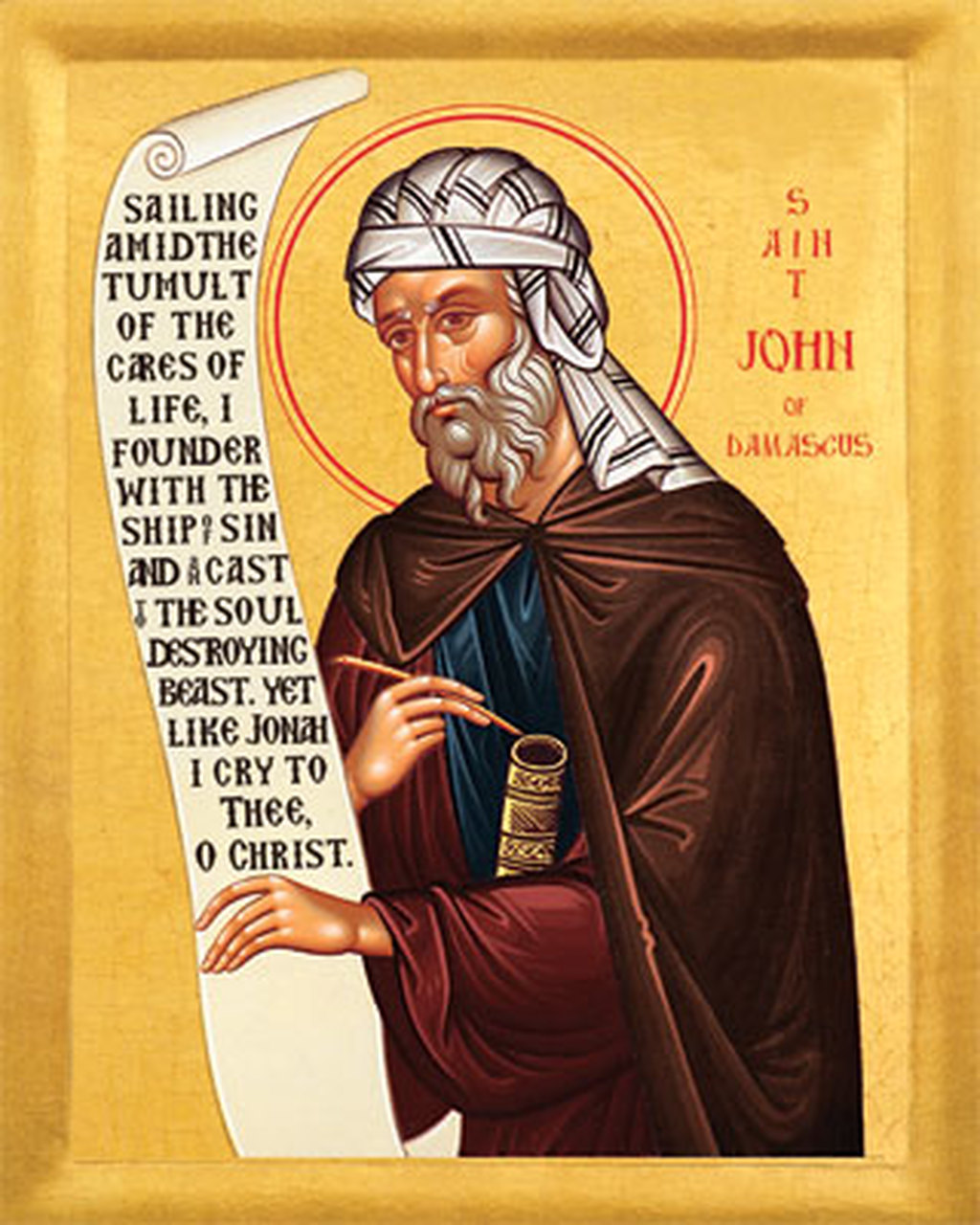

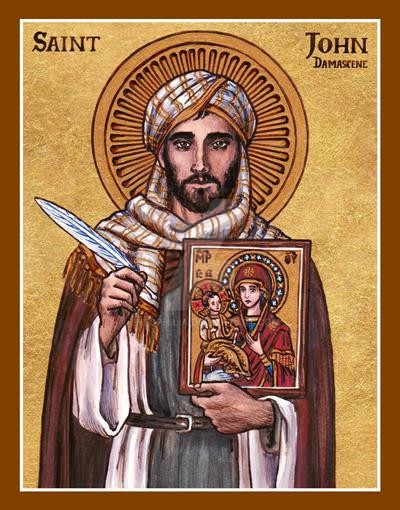

Today, the Church celebrates the feast of St. John of Damascus, a monk and Doctor of the Church, who was a strong proponent for the use of icons. He says the following in favor of the practice of venerating icons:

“We use all our senses to produce worthy images of Him, and we sanctify the noblest of the senses, which is that of sight. For just as words edify the ear, so also the image stimulates the eye. What the book is to the literate, the image is to the illiterate. Just as the words speak to the ear, so the image speaks to the sight; it brings us understanding.” (On the Divine Images,1, 17)

Icons captivate the eye, but they are not merely pieces of art that hang on walls. They bring “understanding.” The image “written” on an icon is meant to draw us into the mystery of Christ’s humanity, to engage our senses in prayer, to help us catch a glimpse of Christ’s face and through that prayer come to know him more. One feature of sacred images that helps bring such understanding is their rich symbolism depicted in the choice of colors of the scene. Gold often represents Christ. White represents purity and divinity. Red represents the humanity of Christ, while green represents earth and temporality. Purple is used to represent nobility. The different colors engage the eye, as to draw one into a meditation of the mystery that is depicted. Because of this, our prayer is made more fruitful and we come to recognize more fully the love Christ has for us.

Advent is a great time to grow in knowledge and understanding of our Lord. The use of icons for prayer during Advent is one way to grow in this knowledge and understanding. Icons helps us to catch a glimpse of salvation, and aid our belief in Jesus Christ. So, during this Advent season, as you are awaiting the arrival of our Lord, consider spending time in prayer with an icon, meditate on the mystery depicted in the scene, and may you come to know Christ’s love for you.”

Love,

Matthew