-by Joel Peters

“It is very interesting to note that in I Timothy 3:15 we see, not the Bible, but the Church – that is, the living community of believers founded upon St. Peter and the Apostles and headed by their successors – called “the pillar and ground of the truth.”

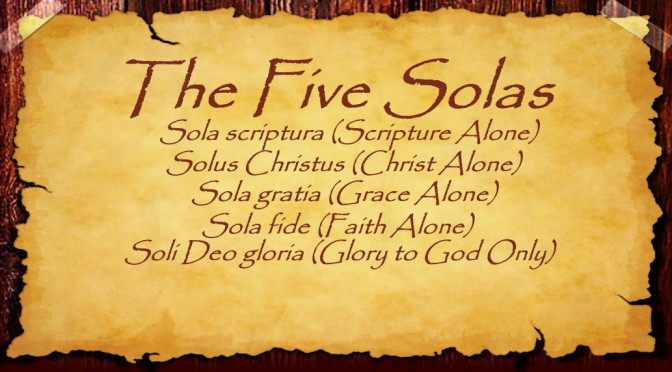

Of course, this passage is not meant in any way to diminish the importance of the Bible, but it is intending to show that Jesus Christ did establish an authoritative and teaching Church which was commissioned to teach “all nations.” (Matt. 28:19). Elsewhere this same Church received Christ’s promise that the gates of hell would not prevail against it (Matt. 16:18), that He would always be with it (Matt. 28:20), and that He would give it the Holy Spirit to teach it all truth. (John 16:13).

To the visible head of His Church, St. Peter, Our Lord said: “And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatsoever thou shalt bind upon earth, it shall be bound also in heaven: and, whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth, it shall be loosed also in heaven.” (Matt. 16:19). It is plainly evident from these passages that Our Lord emphasized the authority of His Church and the role it would have in safeguarding and defining the Deposit of Faith.

It is also evident from these passages that this same Church would be infallible, for if at any time in its history it would definitively teach error to the Church as a whole in matters of faith or morals – even temporarily – it would cease being this “pillar and ground of the truth.” Since a “ground” or foundation by its very nature is meant to be a permanent support, and since the above-mentioned passages do not allow for the possibility of the Church ever definitively teaching doctrinal or moral error, the only plausible conclusion is that Our Lord was very deliberate in establishing His Church and that He was referring to its infallibility when He called it the “pillar and ground of the truth.”

The Protestant, however, has a dilemma here by asserting the Bible to be the sole rule of faith for believers. In what capacity, then, is the Church the “pillar and ground of the truth” if it is not to serve as an infallible authority established by Christ? How can the Church be this “pillar and ground” if it has no tangible, practical ability to serve as an authority in the life of a Christian? The Protestant would effectively deny that the Church is the “pillar and ground of the truth” by denying that the Church has the authority to teach.

Also, Protestants understand the term “church” to mean something different from what the Catholic Church understands it to mean. Protestants see “the church” as an invisible entity, and for them it refers collectively to all Christian believers around the world who are united by faith in Christ, despite major variations in doctrine and denominational allegiance. Catholics, on the other hand, understand it to mean not only those true believers who are united as Christ’s Mystical Body, but we simultaneously understand it to refer to a visible, historical entity as well, namely, that one – and only that one – organization which can trace its lineage in an unbroken line back to the Apostles themselves: the Catholic Church. It is this Church and this Church alone which was established by Christ and which has maintained an absolute consistency in doctrine throughout its existence, and it is therefore this Church alone which can claim to be that very “pillar and ground of the truth.”

Protestantism, by comparison, has known a history of doctrinal vacillations and changes, and no two denominations completely agree – even on major doctrinal issues. Such shifting and changing could not possibly be considered a foundation or “ground of the truth.” When the foundation of a structure shifts or is improperly set, that structure’s very support is unreliable (cf. Matt. 7:26-27). Since in practice the beliefs of Protestantism have undergone change both within denominations and through the continued appearance of new denominations, these beliefs are like a foundation which shifts and moves. Such beliefs therefore cease to provide the support necessary to maintain the structure they uphold, and the integrity of that structure becomes compromised, Our Lord clearly did not intend for His followers to build their spiritual houses on such an unreliable foundation.”

Love,

Matthew

(Editor’s note: a dear friend who converted to Catholicism, and holds an MA in Catholic theology posed the following question to me after I sent this post to him:

“From: your dear friend

Date: Thursday, May 5, 2016 at 7:23 AM

To: “Matthew P. McCormick” <matthew.mccormick11@yahoo.com>

Subject: Re: Sola Scriptura?: Bible calls Church “Pillar & Ground of Truth” & not itself

Matthew, see below:

in·fal·li·ble

inˈfaləb(ə)l/

adjective

-incapable of making mistakes or being wrong.

I believe Catholicism to be the true faith.

But how can he assert the Catholic Church is incapable of being wrong?

What about the 19th century when it denounced evolution? What about when the church held the earth was flat?

More recently, the Church has changed its teaching on a variety of things such as who gets to heaven, and on and on.

Finally, I though that Catholic doctrine held that Christians make up one universal church with Protestants and Eastern Orthodox believers simply not in communion with us. He seems to say that is not the case.

Do you agree?

Thanks,

Your dear friend”

“From: “Matthew P. McCormick” <matthew.mccormick11@yahoo.com>

Date: Thursday, May 5, 2016 at 7:50 AM

To: my dear friend

Subject: Re: Sola Scriptura?: Bible calls Church “Pillar & Ground of Truth” & not itself

My dear friend, this is an amateur layman’s interpretation, my opinion, take it for what it’s worth. You could ask the author yourself, too. If you click on his name in the post it will take you to his Linkedin page. He should be easy to reach. You MAs in theology can hash it out from there. I’m only working on mine. “I just work here!” 🙂

This word is misinterpreted by everyone. I think there are two uses. One narrow and VERY specific, papal infallibility, and then the other MUCH broader and general. The first use is for doctrine which is forbidden to be contested. What almost everyone fails, and few Catholics care to distinguish, is what level of teaching authority of the Church is the Church teaching this in question teaching? Priestly celibacy is a discipline not doctrine. It could be easily changed. There are cultures that would tremble globally and others that wouldn’t even have a pulse about such a change. The last teaching, and ONLY one, I can think of right now, that exercised papal infallibility, is the Immaculate Conception, but as Joel points out, this has been an oral tradition from the beginning, and I believe him.

The second is the general infallibility guaranteed by the Holy Spirit. You can’t exactly have THE TRUE CHURCH which only has a variable probability of getting it right, now can you? Either, as I understand both Joel and the doctrine, you believe in the power of the Holy Spirit to help God’s instrument on earth “get it right”, or you don’t, which distinctly and directly implies doubt and a lack of faith in the promises of Christ? And, the Holy Spirit? This is how I understand what he is saying. You should check with Joel, too. Let me know what he says, please. Thank you for reading the stuff I send and your thoughtful question. It is how we reach that infallible Truth!! Always has been.

I hear what you are saying, but I would also recommend to you, even though highly impractical, to do scholarly research, or find someone who has on each of the positions below you claim the Catholic Church has held and qualify, precisely, in detail, what the Church’s position exactly was, and whether it declared each, even if as you describe, to the level of infallibility? I doubt, based on experience, you will find the convicting evidence you suggest? I doubt it. You must give the Curia credit for being universal and eternal masters of language and taking the charge of infallibility through the Holy Spirit most seriously. Any teaching, if there is any doubt, can’t hope to reach the level of doctrine, in my experience. The Curia really are superstars of language and thought, and would NEVER be careless with regard to doctrine, let alone any lesser degree of authoritative teaching, which is why I suggest scholarly research on your understandable, but albeit gross, albeit imprecise, albeit general myths you assert?

If you can find the citation where the Church says “whatevs”, let me know. I am not aware. The Church’s long standing doctrine of “extra ecclesiam nulla salus” has NEVER CHANGED!!!! The big news from Vatican II was the Church, formally, and in writing, said, and I quote, “it is possible”, NOT normative, NOT usual, NOT to be expected by the rational person, but merely, “possible”, and did not indicate a likelihood, and certainly NOT a healthy or reliable one, for salvation to occur outside the Church; AND, ONLY under very specific and defined categories, I.e. baptism by blood, desire, water, invincible ignorance, i.e. unaware the Catholic Church exists, try and BET YOUR SOUL on THAT ONE!!!!, etc. Good luck!!! Many people misread, Gaudium et Spes, and think it says “whatevs”. Nothing could be further from the truth!!!

Simply being a Catholic is absolutely NO GUARANTEE of salvation. We never know in this life. We trust in our Lord’s promises & His mercy; faith, not de facto salvation. Only of the saints do we have some surety of their salvation and being in Heaven with Jesus, hence the miracles. Finally & frankly, that is merely what canonization does and means is to confirm and promulgate the formal earthly understanding of the FAR GREATER, more momentous, and of greater import fact, that these souls, truly, “have been made worthy of the promises of Christ!!!! Praise Him, Church!!!! Praise Him!!!!

-humbly & in Christian love,

Matthew”)