Catholics believe we are justified by God’s grace. Christ has redeemed the whole world. We must freely choose, free will, to cooperate in that redemption. It’s that word “cooperate” that’s the rub here. Protestantism, I generalize, begins with Sola Fide, salvation through faith, alone, although none of the Five Solas are found in the Bible, aka Sola Scriptura. It’s that word “alone” that’s the rub here. Since belief in “faith alone” implies all one need do is declare “I believe!”, and one is “saved”, and grace is part of the package deal. One and done.

However, back to that word “cooperate”, Catholics feel that while that’s an awesome start, throw in Baptism, by necessity, and you’re rolling, but out of the pure joy of the prospect of salvation, you MUST, not optional, act. James 2:14-26. Catholics are never “assured” of salvation, and surely NEVER from anything we DO, that would be the heresy of Pelagianism. And, to say we were assured of salvation simply by saying “I believe!”, that would be presumption, a form of the sin of pride, by which Satan fell, presuming a declaration/decision belonging to God alone at the time of our particular judgment. We have reasonable confidence in the fact the saints are in Heaven, hence the ask for miracles in canonization as a sign of this fact.

To the Catholic mind you cannot just go on living your life as if nothing had happened or slip back into sin or immorality just because you said “I believe!”. You must, through His grace, ask for grace. ALL is grace!!!! ALL!!! It is free. It is granted to those who ask. Mt 7:7. Through grace, asked for & received, I cannot explain it, but try it, sincerely. (I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised. I know I am, over and over again. And, we’re not just taking natural phenomena and calling it “grace”. It’s subtle, but I do believe, from personal witness, it exists and is effective.) That through God’s unmerited favor, we will be able to live holy and holier lives as God commands. We are wounded by Original Sin, so this is NOT going to be easy!!! But, it is possible, Jesus commands it. Mt 5:20. Never through our own efforts, but by His unmerited favor, grace, which makes all of this possible. Praise Him!!!

-by Br John Paul Kern, OP

“Do Catholics and Protestants both believe that we are saved by God’s grace?

Yes! And today many Christians are realizing that this is an essential point of Christian unity.

In 1999, the Catholic Church and Lutheran leaders signed a Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, proclaiming together that “all persons depend completely on the saving grace of God for their salvation” (JDDF, 19).

In 2006, Methodist leaders affirmed that this statement “corresponds to Methodist doctrine.” This summer, on the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, leaders of the Reformed communities also accepted this common explanation of justification by grace.

What does this groundbreaking agreement between the Catholic Church and Protestant leaders mean?

After many years of harsh rhetoric and, often, misunderstandings, the Catholic Church and several large Protestant communities have been able to acknowledge together, publicly, that we both believe that Christians are saved by grace. Acknowledging such common ground is an important step toward a fuller Christian unity.

However, many Protestants remain skeptical that the Catholic Church affirms the priority of God’s grace in man’s justification, which Luther called the “first and chief article” of Christian faith (Smalcald Articles, II.1). Additionally, the Joint Declaration itself openly acknowledges and describes differences in the way that Catholics and Protestants understand how we are saved by grace.

Unfortunately, many Catholics and Protestants alike are unfamiliar with both the Catholic doctrine of justification by grace and the teachings of the Protestant Reformers. Therefore, let us explore what we share in common as well as where we differ regarding “the Gospel of the grace of God” (Acts 20:24), to better appreciate this beautiful, saving truth in its fullness.

Common Ground: The Primacy of God’s Grace in Man’s Salvation

God, Who is rich in mercy, out of the great love with which He loved us, even when we were dead through our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ (by grace you have been saved)… For by grace you have been saved through faith; and this is not your own doing, it is the gift of God—not because of works, lest any man should boast. (Eph 2:4–5, 8–9)

St. Paul knew from his own conversion that salvation in Jesus Christ comes through God’s gift of grace. Therefore, he strongly emphasized this central Gospel truth throughout his writings.

Having also undergone a radical conversion by God’s grace, St. Augustine of Hippo (354–430) famously rejected the error of Pelagius, who claimed man could save himself apart from grace.

The Catholic Church later employed St. Augustine’s teachings to refute “semi-Pelagianism”—the claim that man can earn the grace of justification by his own efforts—at the Second Council of Orange (529), and she continues to honor St. Augustine as the Doctor Gratiae (Teacher of Grace).

A thousand years later, Protestant theologians in the 16th century articulated their doctrine of justification sola gratia (by grace alone), which also emphasized the priority of grace.

When the Catholic Church promulgated her official response at the Ecumenical Council of Trent (1546–1563), she strongly reaffirmed the primacy of God’s grace. Once again, she explicitly rejected Pelagianism—the claim “that man may be justified before God by his own works… without the grace of God”—and Semi-Pelagianism.

Thus, the Catholic Church in the 16th century authoritatively agreed with the Protestant Reformers regarding the priority of grace in salvation. However, she was concerned that the Protestant doctrine of sola gratia greatly reduced the scope and power of the grace of justification by emphasizing God’s forgiveness apart from the effects of grace on man.

Therefore, the Catholic Church emphasized, and continues to emphasize, that God’s grace of justification cannot be understood in its fullness apart from:

- the role of grace in God’s entire plan for mankind;

- a radical transformation, renewal, and rebirth of the human person; and

- God’s elevation of man to partake of the divine nature and participate in divine life.

1. Grace is a Fundamental Part of God’s Entire Plan for Humanity

For Protestant Reformers, such as Luther, the central question was justification: how can a sinful person be justified before God? This is extremely important. However, a singular emphasis on this question often leads Protestants to view grace solely through the lens of “solving the problem” of justification.

Catholics, on the other hand, understand God’s grace not only as a merciful response to man’s miserable, fallen state after sin but also as a generous gift that God freely and lovingly chose to bestow upon Adam and Eve from the moment of their creation. The Catholic faith teaches that God created man in a state of grace, which allowed him to enjoy an intimate friendship with God, knowing and loving God in a way that would not have been possible without God’s grace.

After the sinful Fall, God’s grace restores man to a state of friendship with God and grants the forgiveness of sin. The Catholic Church teaches that God’s prevenient (prior) grace prepares, disposes, and moves man to freely receive the grace of justification, which communicates to man the righteousness of Christ. From beginning to end, it is grace that saves.

Starting at the moment of justification, Christian life is animated by sanctifying grace, which allows Christians to grow in holiness throughout their lives. Sanctifying grace includes the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity, the heart of the Christian life (1 Cor 13:13), and the gifts of the Holy Spirit (Isa 11:2). Christians who follow the Holy Spirit through the gifts enjoy the fruits of the Spirit (Gal 5:22–23), the highest of which are the Beatitudes (Matt 5:3–12).

Finally, the life of grace reaches its full fruition in the glory of heaven. It is not by man’s natural powers that he is capable of beholding the beatific vision of God but only by God’s gift of the light of glory, which is also a grace.

2. God’s Grace Has the Power to Actually Transform a Human Person

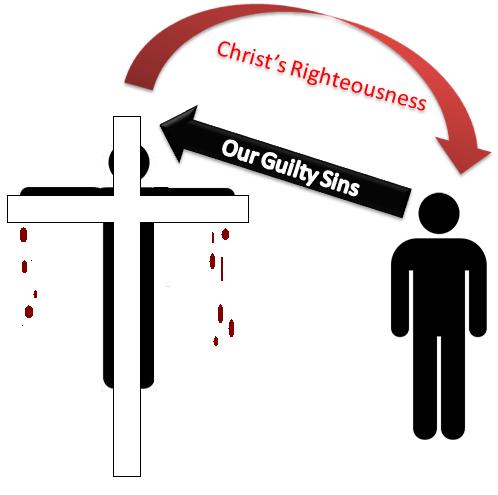

According to the Protestant Reformers, justification by grace is extrinsic to man. That is, justification describes man’s standing before God, in a sort of legal fashion, rather than the actual state of man himself. According to Luther, for example, man is justified when God graciously looks at Christ’s merit, which covers but does not destroy man’s sin, and imputes (credits) to us the “alien righteousness” of Christ, declaring us righteous by a judicial act though we remain sinners in reality. Thus, grace is simply the “undeserved favor” of God’s merciful judgment, which renders us “not guilty.”

In contrast, the Catholic faith teaches that while the wounds due to original sin still affect Christians, the grace of justification does not merely cover sin but destroys it, regenerates man to spiritual life (Jn 3:3; Titus 3:4-7), and restores his friendship with God.

Scripture recounts Jesus forgiving sins (Mk 2:1-12), casting out evil (Lk 11:14), healing (Mt 8:1-4), and raising people from the dead (Jn 11:40-44), all of which serve as powerful images for what God accomplishes in the human soul through the grace of justification.

God’s declarations match reality. God spoke the universe into being by saying, “let there be…” (Gen 1). Similarly, when God declares a person to be just and righteous, he simultaneously and actually makes that person just and righteous by the power of his grace, “so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor 5:21).

The grace of justification communicates the righteousness of Christ to man and has the power to actually transform man into the image of Christ (Rom 8:29). The Christian is reborn to a new life of grace infused by the Holy Spirit and is given a new heart (Ez 36:26–28), a new mind (1 Cor 2:16), and a new “nature” in Christ (Eph 4:22–24).

St. Paul explains, “if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old has passed away, behold, the new has come” (2 Cor 5:17). Thus, Christians transformed by grace have “put off the old nature with its practices and have put on the new nature, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its creator” (Col 3:9–10).

Therefore, “justification… is not only the remission of sins, but also the sanctification and renewal of the inward man [2 Cor 4:16] through the voluntary reception of the grace… whereby man who was unjust becomes just [Rom 3:23-24], and who was an enemy becomes a friend [Jn 15:15], so that he may be an heir according to hope of life everlasting” (Trent, Decree on Justification, Ch. 7).

God justifies a person by an infusion of grace, which brings about a transformation of the soul from a state of sin and injustice to a state of grace, justice, and righteousness. This conversion includes a movement of the intellect toward God in faith and a movement of the will to love God and to hate sin, and it simultaneously results in the forgiveness of sin (Summa Theologica I-II, q. 113, a. 6).

Thus, in his work of justification, God’s undeserved favor actively bestows upon us the gift of grace, which has the power to actually transform us and make us righteous with the righteousness of Jesus Christ.

3. By Grace We Partake of the Divine Nature and Participate in Divine Life

The Protestant Reformers also do not emphasize what is, perhaps, the most amazing thing about grace: that God’s grace elevates Christians to share in God’s Trinitarian life of love. Luther asserted that even “the just sin in every good work” (Denzinger, 771), and “every work of the just is worthy of damnation… if it be considered as it really is” (Möhler, “Symbolik,” 22). For Calvin, even Christian acts of charity “are always defiled by impurity” (Institutes, III, 18, 5).

In contrast, St. Peter wrote, “his divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness… that through these you may escape from the corruption that is in the world because of passion, and become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet 1:3–4).

From the very beginning, “God… freely created man to make him share in his own blessed life” (CCC 1). That is, God created us to partake, by grace, in his own divine nature and to share in the divine life of Trinitarian love (1 Jn 4:7-16)—a life that is far above and beyond what is possible by human nature alone.

Even after original sin, God’s grace restores us from spiritual death to new life in Christ (Rom 6:4). Grace allows us to share in God’s own Trinitarian life as “adopted sons” in the Son (Gal 4:4–6) and as “children of God” (Jn 1:12–13) so that through, with, and in Jesus Christ, by the indwelling and power of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor 6:19), we may call God “Our Father” (Mt 6:9).

By grace, we are truly united to Christ as his members (1 Cor 12:12–27), and the life of the divine vine runs through us as branches (Jn 15:1–11), so that with St. Paul we may proclaim that it is now “Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:20). As God’s children in Christ, we cooperate with God’s grace to bear the spiritual fruit of good works (Jn 15:16–17; Eph 2:10), which glorify God.

This supernatural life of grace, which begins on earth, blossoms into the life of glory in heaven. There, the gift of faith will be transformed into sight as we behold God face-to-face (1 Cor 13:12). Our hope will be fulfilled as we possess God, our eternal inheritance and reward, celebrating the wedding feast of the Lamb (Rev 19:6-9). Yet love, the core of the Christian life, will continue, perfected, in heaven as we experience the fullness of joy praising God for all eternity (1 Cor 13:8). Thus, the life of grace will be crowned and fulfilled in eternal life.

By grace, even now, we can share in God’s life of love and, in imitation of Jesus Christ, perform the works of our Father (Jn 4:34). Let us cry out “Abba! Father!” in praise of him whose merciful love offers us, by the saving work of his Son, through the Holy Spirit, this amazing gift of grace!”

Love, & always begging for His grace,

Matthew