“The Catholic ideal of married life is rigorous and difficult. Catholic spouses are to surrender their own selfish interests in service to a transcendent goal — to bring one’s spouse and one’s children to God. Sometimes that self-surrender calls for enormous and painful sacrifice, just as Jesus sacrificed Himself on the Cross for the sake of the Church. Most importantly, the Catholic Church recognizes Christian marriage as a sacrament, which means that God promises us the grace to meet those difficult demands.

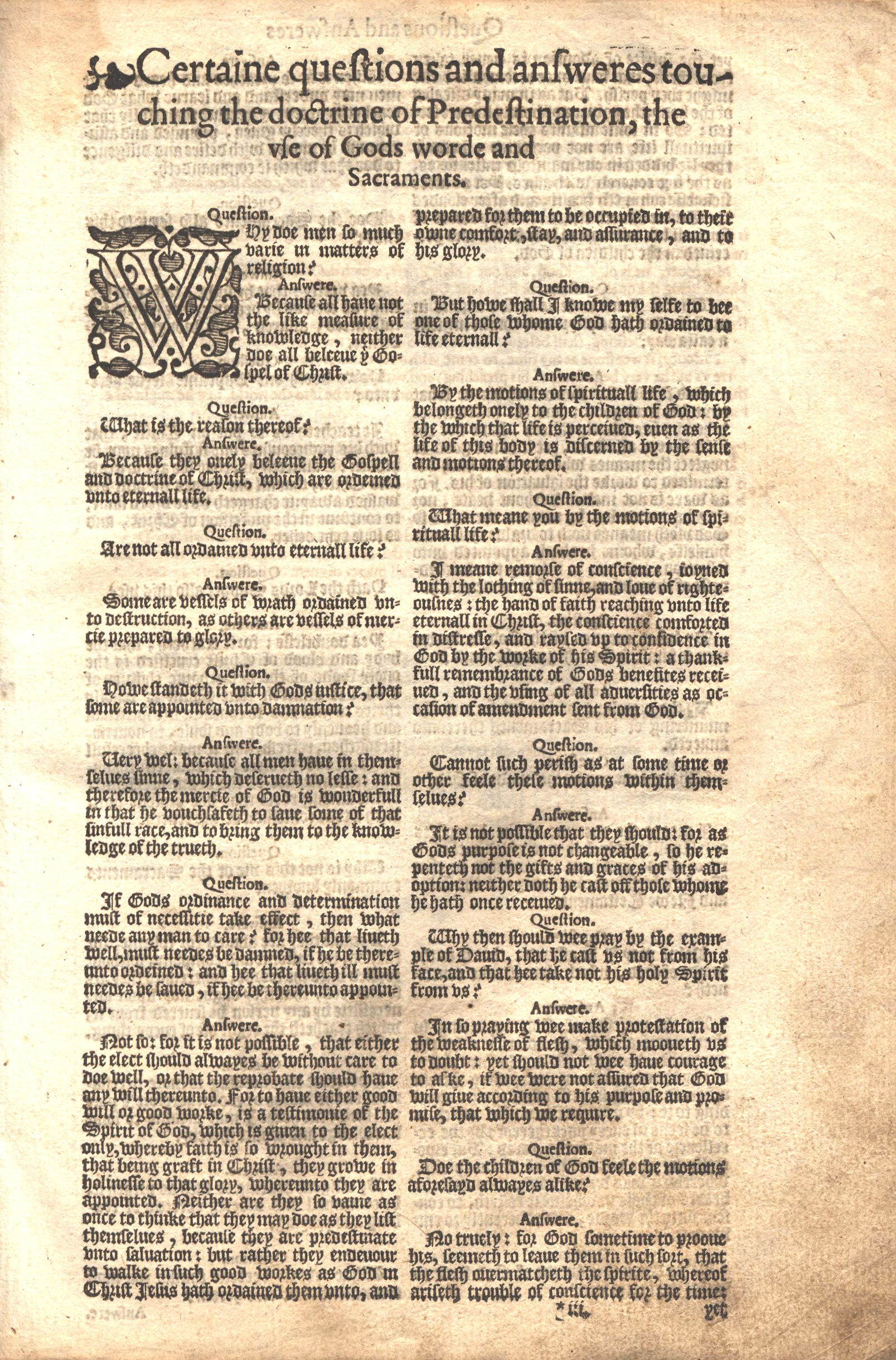

Early Protestants, on the other hand, simply denied that marriage is a sacrament. Instead, they threw up their hands and asserted that the demands of Catholic marriage were too difficult. Therefore, they called for a relaxation of those demands and an end to the Church’s control over marriage. Protestant thought went on to emphasize more strongly the sexual dimension of married life, and eventually the romantic element as well, while deemphasizing the role that suffering plays in union with God.

My Protestantism offered me little solace in the face of a hopeless marriage, but Catholicism seemed to offer me a way to reconceive my suffering. Suffering willingly embraced becomes sacrifice, and sacrifice can bring a deeper experience of God’s grace….

I started thinking about the differences between Protestant and Catholic notions of sex and marriage. I discerned four major differences between the two traditions:

1. The Catholic tradition opposes both contraception and sodomy in marriage. Most Protestants allow them.

2. The Catholic Church exalts virginity, celibacy, and perfect continence over marriage. The Protestant tradition has always rejected this.

3. The Catholic Church does not allow Christian divorce and remarriage. Although Protestantism values lifelong fidelity in a broad sense, Protestant tradition has always allowed divorce in at least a few circumstances, such as adultery.

4. The Catholic Church regards Christian marriage as a sacrament that conveys grace. As a sacrament, Christian marriage (not all marriage) ought to be governed by Church law.

Protestant tradition, rather, has always asserted that God ordains marriage, but not as a sacrament. For Protestants, marriage is a civil institution rightly governed by civil law. Protestants and Catholics have different views of marriage, I came to understand, because they have different views about the foundational concepts of morality, spirituality, salvation, and human happiness. Catholics believe that the ultimate end of human life is loving union with God and neighbor. Aided by grace, we ought to bend every fiber of our being toward that end. Catholic ideas about marriage and contemplative life reflect that lofty calling.

The Protestant tradition also extols loving union with God but has always been more skeptical about the Christian’s moral potential. Catholics take quite seriously Christ’s command to “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matt. 5:48). Relying on God’s grace through prayer and the sacraments, and through diligent cooperation with grace, Catholics believe that all God’s commands can be obeyed. By contrast, the Protestant tradition teaches that sin always remains and that perfect holiness in this life is impossible. Early Protestants argued, therefore, that we ought to relax the discipline of Christian life (including marriage) to accommodate human weakness…

Catholic marriage: “It is a love which is total — that very special form of personal friendship in which husband and wife generously share everything, allowing no unreasonable exceptions and not thinking solely of their own convenience. Whoever really loves his partner loves not only for what he receives, but loves that partner for the partner’s own sake, content to be able to enrich the other with the gift of himself.” –Pope Paul VI, encyclical letter Humanae Vitae (July 25, 1968), no. 9.

If you approach married life in that way, it becomes impossible to objectify your spouse for your own gratification. Instead, you beg for God’s grace and bend every fiber to order your life toward this transcendent goal. You would be willing to bear suffering, abstinence, and abnegation if they serve that great good. You would, in fact, learn to imitate Christ…

The ideal of celibacy reminds all Christians that the goal of life is spiritual friendship, not personal aggrandizement or pleasure seeking. A few Christians can take up that life in radical detachment from the world, but many more Christians live spiritual friendship through marriage.

The Christian ideal of marriage was very different from the ancient Roman practice. Pagan society expected chastity of women, but not of men. Roman men were allowed prostitutes and concubines, and then to avoid the unwanted consequences of such promiscuity they resorted to forced abortions, infanticide, and rudimentary and extremely harmful contraceptives. Women suffered disproportionately from these practices, which became one of the reasons Roman women were more likely than men to become Christian. The Catholic doctrine on chastity was liberating.

The Catholic Church advocated personal commitment to God over all other social commitments, even for women. This was a particularly radical idea in patriarchal Rome, where women were expected as a matter of course to acquiesce to the will of men. The Church, however, venerated virgin martyrs, such as St. Lucy, who went to their deaths for refusing to marry against their will. Unlike many other cultures of the era, canon law has refused from the very beginning to recognize the validity of forced marriage.

“How beautiful, then, the marriage of two Christians, two who are one in hope, one in desire, one in the way of life they follow, one in the religion they practice. They are as brother and sister, both servants of the same Master. Nothing divides them, either in flesh or in spirit. They are, in very truth, two in one flesh; and where there is but one flesh there is also but one spirit. They pray together, they worship together, they fast together; instructing one another, encouraging one another, strengthening one another. Side by side they visit God’s church and partake of God’s Banquet; side by side they face difficulties and persecution, share their consolations. They have no secrets from one another; they never shun each other’s company; they never bring sorrow to each other’s hearts. Unembarrassed they visit the sick and assist the needy. They give alms without anxiety; they attend the Sacrifice without difficulty; they perform their daily exercises of piety without hindrance. They need not be furtive about making the Sign of the Cross, nor timorous in greeting the brethren, nor silent in asking a blessing of God. Psalms and hymns they sing to one another, striving to see which one of them will chant more beautifully the praises of their Lord. Hearing and seeing this, Christ rejoices. To such as these He gives His peace. Where there are two together, there also He is present; and where He is, there evil is not.” –Tertullian, “To His Wife,” in Treatises on Marriage and Remarriage, Ancient Christian Writers Series, no. 13, trans. William P. LeSaint, S.J. (Westminster, MD: Newman Press, 1951), 35–36.

…The differences between Protestant and Catholic teaching on marriage have their roots in two fundamental issues. First, the Protestant Reformers thought that Catholic teaching on human sexuality was just too difficult. Second, the Reformers resented the authority that the Catholic Church exercised over Christian marriage. The way they tried to solve these “problems” theologically was to naturalize Christian marriage, removing it from the realm of the supernatural. A major part of the Reformation, therefore, was an attack on the sacramentality of Christian marriage.

The Reformers never denied that God instituted marriage at the creation of Adam and Eve. They simply denied that Christ elevated marriage to a sacrament. “Marriage is a good and holy ordinance of God,” Calvin wrote, “and farming, building, cobbling, and barbering are lawful ordinances of God, and yet are not sacraments.” –Institutes of the Christian Religion, 4.19.34.

…In 1 Corinthians 6, St. Paul teaches that Christians must not engage in sexually immoral behavior. That is not terribly surprising. What is surprising is the reason he gives. “Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ?” Paul writes, “Shall I therefore take the members of Christ and make them members of a prostitute? Never!” (1 Cor. 6:15).

In this text, Paul teaches that a Christian’s very body has been permanently changed in a way that identifies him with Christ and thereby affects his sexuality. The Christian literally carries the body of Christ with him into the marriage bed. While I found the idea to be somewhat arresting, I quickly saw that it had profound implications for the doctrine of marriage. If two baptized people got married, then Christ would necessarily be implicated in a very profound, very intimate way in their union.”

Anders, Dr. David. The Catholic Church Saved My Marriage: Discovering Hidden Grace in the Sacrament of Matrimony (pp. 53-56, 58-59, 63-64, 67-68). Sophia Institute Press. Kindle Edition.

Love,

Matthew