![Matt Talbot Icon [1600x1200]](https://soul-candy.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Matt-Talbot-Icon-1600x1200.jpg)

“Non nobis, Domine!!!” -Not to us, Lord, not to us, but to Your Name give the GLORY!!!” -Ps 115:1

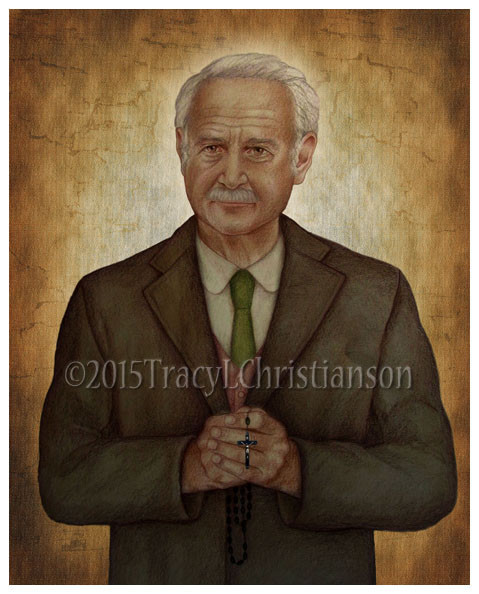

It is more rare to find someone who doubts the existence of Hell; Hell being so much easier to believe in. There are so many practical, real, and terrifying examples here on Earth. Matthew Talbot is an intercessor and exemplar for those who struggle with addiction: to drugs, alcohol, pornography, sex, pride, power, gossip/scandal, greed, vanity, envy, wrath, narcissism, doubt, willfulness, ego, cynicism, bad habits/sins, lust, gluttony, even god, in a dark way, where actually, god is ourselves, or far worse, but that’s pretty bad enough.

Jesus resurrects from the dead, from the corruption, darkness, and silence of the tomb; Himself and us, into endless light, freshness, and rejoicing. Seek Him, while He may be found. He invites you, passionately. He does.

Matthew Talbot, “the saint in overalls”, was born on May 2, 1856, the second of 12 siblings, in Dublin, Ireland. He had three sisters and nine brothers, three of whom died young. His father Charles was a dockworker and his mother, Elizabeth, was a housewife. From his early teens until age 28 Matt’s only aim in life was to be liquor. But from that point forward, his only aim was God.

Compulsory school attendance was not in force, and Matt never attended any school regularly. When Matthew was about 12 years old, he got his first job, at E & J Burke Wine Merchants, and started to drink alcohol. His father was a known alcoholic as well as all his brothers. Charles tried to dissuade Matthew with severe punishments but without success.

Matthew, a regular guy if ever there was one, then worked as a messenger boy and then transferred to another messenger job at the same place his father worked. After working there for three years, he became a bricklayer’s laborer. He was a hodman, which meant he fetched mortar and bricks for the bricklayers. He was considered “the best hodman in Dublin.”

As he grew into an adult, he continued to drink excessively, He continued to work but spent all his wages on heavy drinking. When he got drunk, he became very hot-tempered, got into fights, and swore. He became so desperate for more drinks that he would buy drinks on credit, sell his boots or possessions, or steal people’s possession so he could exchange it for more drinks. He refused to listen to his mother’s plea to stop drinking. He stole the violin from a blind fiddler and pawned it. He eventually lost his own self-respect. One day when he was broke, he loitered around a street corner waiting for his “friends”, who were leaving work after they were paid their wages. He had hoped that they would invite him for a drink but they ignored him. Dejected, humiliated, and devastated, he went home and publicly resolved to his mother, “I’m going to take the pledge.” His mother smiled and responded, “Go, in God’s name, but don’t take it unless you are going to keep it.” As Matthew was leaving, she continued, “May God give you strength to keep it.”

Matthew went straight to confession at Clonliffe College and took a pledge not to drink for three months. The next day he went back to Church and received communion for the first time in years. From that moment on, in 1884 when he was 28 years old, he became a new man. After he successfully fulfilled his pledge for three months, he made a life long pledge. He even made a pledge to give up his pipe and tobacco. He used to use about seven ounces of tobacco a week. He said to the late Sean T. O’Ceallaigh, former President of Ireland, that it cost him more to give up tobacco than to give up alcohol.

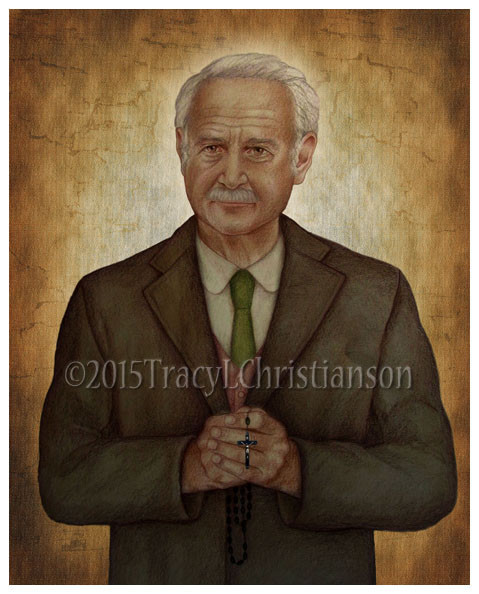

The newly converted Matthew never swore. A member of the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Matt made sure he never carried money with him to help himself avoid temptation. He was good humored and amicable to everyone. He continued to work as a hodman and then as a laborer for T&C Martins Lumberyard. He used his wages to pay back all his debts. He lived modestly and his home was very spartan. He developed into a very pious individual who prayed every chance he got. He attended Mass every morning and made devotions like the Stations of the Cross or devotions to the Blessed Mother in the evenings. He fasted, performed acts of mortification, and financially supported many religious organizations. He read biographies of St. Teresa of Avila, St. Therese of Lisieux, and St. Catherine of Siena. He later joined the Third Order of St. Francis on October 18, 1891 even though a young pious girl proposed to marry him. Physically, he suffered from kidney and heart ailments. During the two times he was hospitalized, he spent much time in Eucharistic adoration in the hospital chapel. Eventually, Matthew died suddenly of heart failure on June 7, 1925 while walking to Mass. He was 69 years old.

On his body, he was found wearing the cilice. While penitential practice has fallen out of fashion, even in Catholic circles, in our modern age, these practices are ancient. Though not popular or fun, penance is the cure for sin. It must always be reasonably moderated and consultation with a healthy spiritual director is always wise.

Penance changes us, allows us to reflect on our errant ways, and is a temporal preventative against a permanent disposition. Even as the athlete trains his body and undergoes physical discomfort for the sake of future performance, so the spiritual athlete does the same. We are creatures of body, mind, and spirit, and so the thinking goes, our engagement in spiritual reform cannot be purely intellectual. Physical discomforts, such as fasting or abstaining from certain foods, make us mindful. As humans, we are all too likely, it is our nature, not to pay attention. It is hard work.

Piety also has fallen out of fashion in our modern age. Matt knelt outside the doors of his church for hours every morning. Once inside, he would prostrate himself on the floor in the form of a cross before entering his pew. Every Sunday, he spent seven hours in Church without moving, “his arms crossed, his elbows not resting on anything, his body from the knees up as rigid and straight as the candles on the altar.” He did this every Sunday for 40 years. One of his favorite little prayers, which he sometimes kept written on his hand, was “O blessed Mother, obtain for me from Jesus that I may participate in His folly.”

-statue in Dublin honoring Venerable Matt Talbot, near Matt Talbot Bridge

“Three things I cannot escape: the eye of God, the voice of conscience, the stroke of death. In company, guard your tongue. In your family, guard your temper. When alone guard your thoughts.”

“Never look down on a man, who cannot give up the drink”, he told his sister, “it is easier to get out of hell!”.

“It is constancy that God seeks.”

-Venerable Matt Talbot

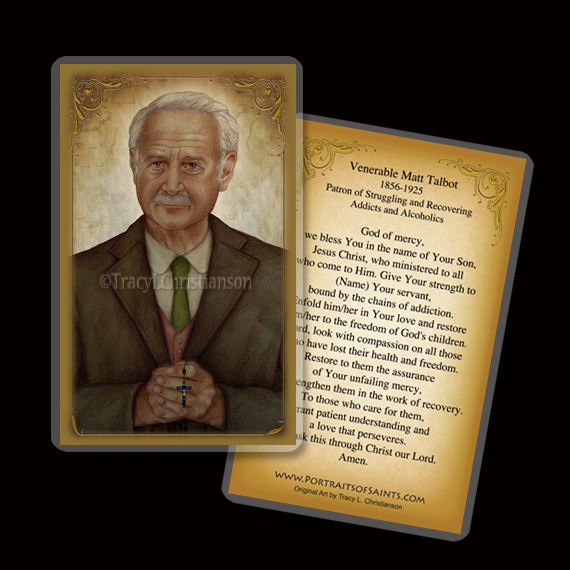

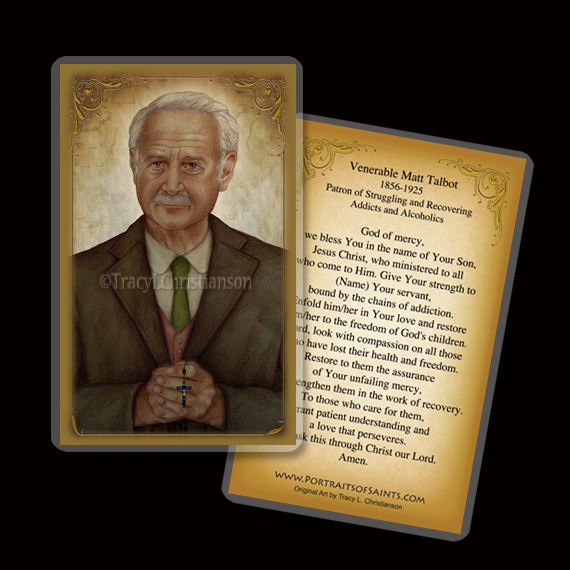

Prayer for the intercession of Matt Talbot:

“May Matt Talbot’s triumph over addiction, bring hope to our community and strength to our hearts, may he intercede for …name… who struggles with his/her addiction, through Christ Our Lord. Amen.”

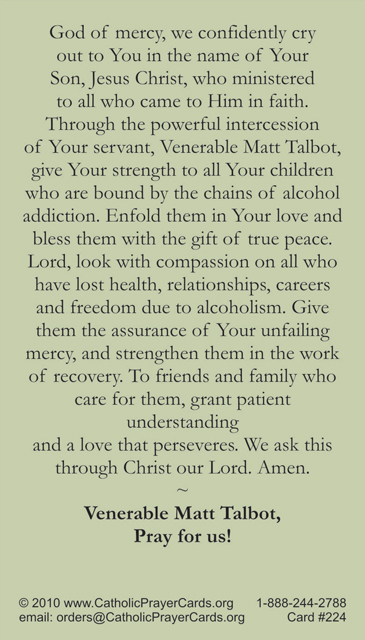

PRAYER FOR THE ADDICTED

God of mercy, we bless You in the name of Your Son, Jesus Christ, who ministers to all who come to Him. Give Your strength to N., Your servant, bound by the chains of addiction. Enfold himlher in Your love and restore himlher to the freedom of God’s children. Lord, look with compassion on all those who have lost their health and freedom. Restore to them the assurance of Your unfailing mercy, and strengthen them in the work of recovery. To those who care for them, grant patient understanding and a love that perseveres. We ask this through Christ our Lord. Amen.

Official Prayer for the Canonization of Blessed Matt Talbot

“Lord, in your servant, Matt Talbot you have given us a wonderful example of triumph over addiction, of devotion to duty, and of lifelong reverence of the Holy Sacrament. May his life of prayer and penance give us courage to take up our crosses and follow in the footsteps of Our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ. Father, if it be Your will that Your beloved servant should be glorified by Your Church, make known by Your heavenly favours the power he enjoys in Your sight. We ask this through the same Jesus Christ Our Lord. Amen.”

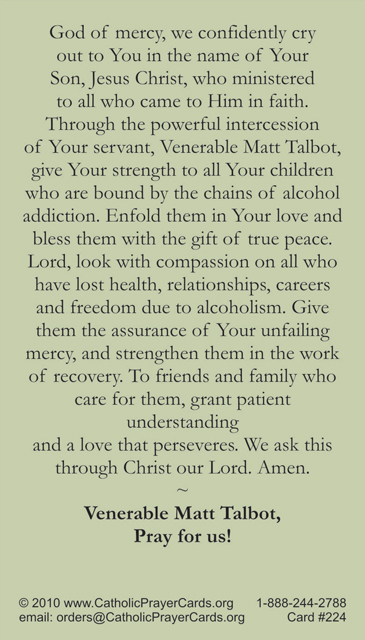

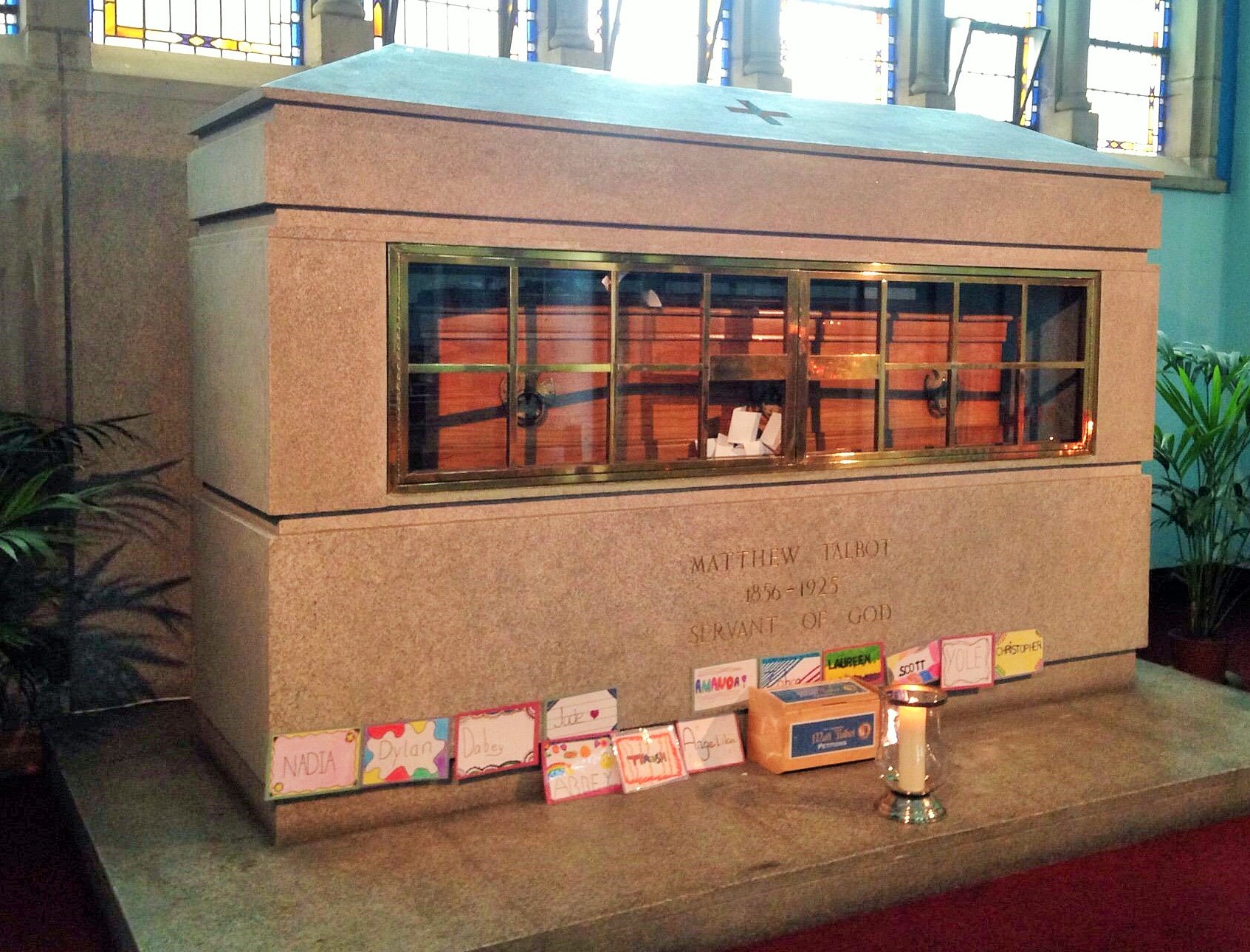

-Matt’s current resting place, the coffin was moved in 1972 and the remains now rest in Our Lady of Lourdes Church,

Sean MacDermott St., Dublin.

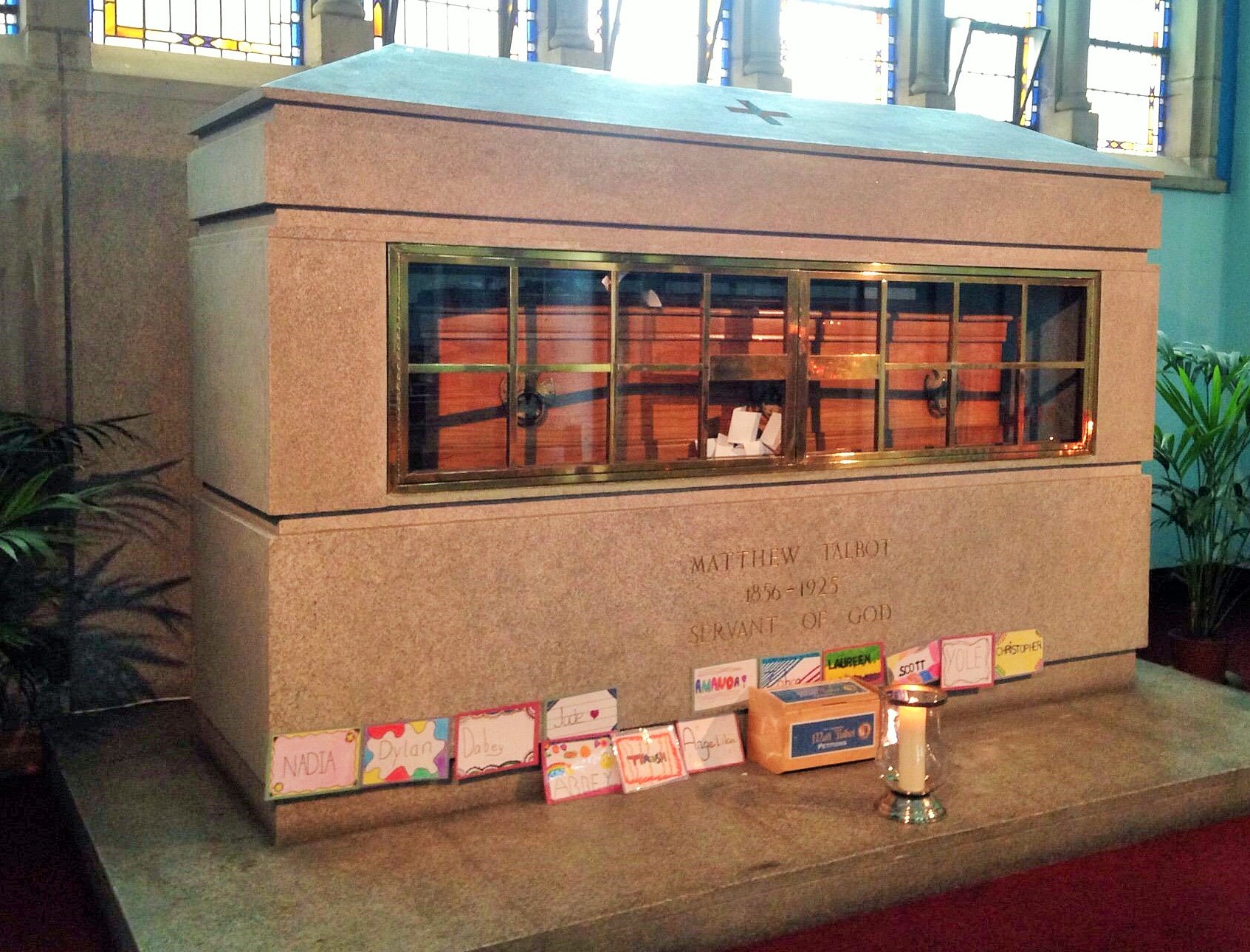

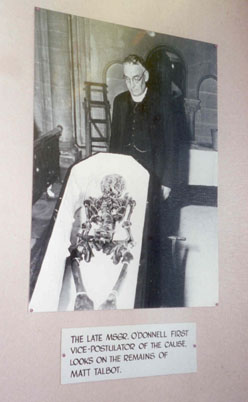

-exhumed

-formal inspection of the remains as official part of the beatification/canonization process

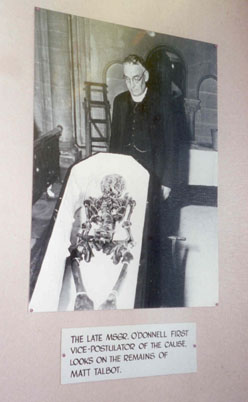

-Matt’s original marker. He was originally buried in a poorer part of Glasnevin Cemetery.

-inspection of Matt’s remains upon transfer

On 8 June 1925, the following news item appeared in the Irish Independent:

“Unknown Man’s Death:

An elderly man collapsed in Granby Lane [Dublin] yesterday, and being taken to Jervis Street Hospital he was found to be dead. He was wearing a tweed suit, but there was nothing to indicate who he was.

What was not reported was the unusual discovery when he was taken to hospital. He was wearing heavy chains: some wrapped around his legs, others on his body. Mortuary staff puzzled over not just who he was but, also, the meaning of the chains.

The newspaper report had appeared on a Monday morning. Later that night, police ushered a woman into the mortuary. She identified the body as that of her brother: Matt Talbot. A nursing nun present asked about the chains. The dead man’s sister replied simply that it was something he wore, and with that, they were placed in the coffin and the lid closed.

That was not the whole story though; the chains were part of the mystery of the man who had died. They were as symbolic as they were real. The man’s life having been a ‘crossing over’ from the servitude of vice to the freedom of those in chains for Christ.

Talbot was born in 1856 into a large Catholic family living in semi-poverty in Dublin. His schooling was slight. He was barely literate when he went to work full-time aged just 11 years old. For the rest of his life his occupation was as an unskilled labourer. He was exposed to harsh working conditions, at times harsh bosses and to a social environment that necessitated some form of release from this – this was found by many in the city’s public houses. Matt was no different, so much so that by his teenage years he was hopelessly addicted to alcohol.

Matt had the reputation of being a hard worker. Increasingly, however, that work ethic was simply the means to finance his ‘hard drinking’. As it grips, vice of whatever sort is hard to counter, especially when the will to oppose it diminishes, so it was with Matt Talbot – what had began as an escape soon became a prison of moral and spiritual degradation. And, the more time he spent there the more Matt needed alcohol to shield him from that reality. Those around watched and, shaking their heads, concluded that Talbot was a lost cause. But they were to be proved wrong and in a most unexpected way.

Fittingly, the second phase of Matt’s life began outside a pub. That day he had no money, and, therefore, hoped that some of his drinking fraternity would stand him a drink. As each acquaintance filed past, none offered to buy him anything. On that summer’s day in 1884, something occurred that was to change Matt Talbot forever. Humiliated by the indifference of his erstwhile friends, he turned and walked straight home. His mother was surprised to see him – at that early hour, and sober. He proceeded to clean himself up before announcing he was going to a nearby seminary to ‘take the pledge’ – a promise to abstain from all alcohol. His mother was mystified by this and fearful. She knew that pledges made to God were not something to be taken lightly. She counselled him against doing any such thing unless he was intent on persevering. He listened, and then left.

Matt did take the pledge that day. He also went to Confession. It was as dramatic as it was decisive. It had all the hallmarks of a genuine conversion, one as sincere as it was needed. Nevertheless, a conversion takes but a moment, the work of sanctity a lifetime: after years of drunkenness, still arraigned against Matt was a weakness of character and a world that revolved around alcohol. It looked as if the odds were stacked against him, but this was not solely a human undertaking. Into this ‘land of captivity’, from ‘across the Jordan’, there came invisible armies to fight alongside this now embattled soul, one embarked upon a war of liberation. This was not a new spiritual combat, but rather one that had commenced many years previously when this poor man’s parents brought a child to a parish church and asked for baptism in the name of the Father, and the Son and the Holy Spirit.

After his conversion, not much changed, outwardly at least: Matt continued with his employment in the docks. He continued to work hard, now respected more than ever by his fellow workers and employers who noticed that he had started to give his wages to his mother rather than straight to a publican. Nevertheless, work alone cannot satisfy the human heart. Previously, when not working his life had been many hours spent in public houses, but, now, he had turned his back on that. He had been ‘born anew’, but like a newborn was vulnerable to the world he inhabited. With no material substance to cling to he turned inward, to the Spirit that dwells within each baptised soul. And, as he did so, he commenced upon an adventure that few could have imagined possible.

From then on, along the Dublin streets, there moved a mystic soul. Each morning at 5AM, dressed in workman’s clothes a man knelt outside a city church waiting for the doors to open and the first Mass to begin. After the Holy Sacrifice, he would pray for a time before going to one of the timber yards near the docks. There, he laboured all day; but there were periods in the day when lulls and breaks would occur. Whilst his fellow workers gossiped or smoked, Matt chose to be alone, knelt in prayer in a hidden part of a workshop until the call came to return to his labors.

***

Each evening, when work was finished, Matt walked home with his fellow workers. They knew their companion’s free time was spent praying in some city church before the Blessed Sacrament. Often he asked them to join him in making a visit to Our Blessed Lord. Some did. After a short while, however, they would leave with Matt still knelt in the gathering twilight. Eventually, when at night he did return home it was to yet more prayer – and mortification. His bed was a plank of wood, a piece of that same material his pillow. Although respected by those he lived amongst and worked alongside, and not unfriendly, he had few visitors. Those who did encounter him felt he was not quite of this world; they were right; he was travelling ever inwards on a mystical journey to a freedom he could never have dreamt of when trapped in an alcoholic stupor.

When his belongings were found after his death, one of the surprises was the number of books he owned. Inquires soon revealed that he had slowly, but determinedly, taught himself to read and, as he did so, effectively began a course of study that included the spiritual classics, the lives of Saints, doctrinal books, and works of mystical and ascetical theology. When asked how he, a poor workman, could read the works of St. Augustine, Newman et al, his reply was as straightforward as it was telling. He said he asked the Holy Spirit to enlighten him. And so, he grew in an intellectual understanding of his faith, which in turn deepened the prayer and penance he undertook. Here was a 20th Century heir to the spiritual traditions of the ancient Irish monks, albeit one now living not on an island monastery but in the slums of Dublin, but, like those earlier contemplatives his life was work, study and prayer with eyes turned ever inward to the Holy Trinity.

Matt never married; held no position of note, was unknown outside his own small circle of family and friends – only one blurred photograph has survived him- and, yet, this was a rare man: one who had taken the Gospel at its word and lived it.

His lifetime ran alongside the then momentous events in Irish history. A time of cultural renaissance and nationalist fervour, of a Great Strike in 1913 and open revolution in 1916, of the Great War and a War for Independence, throughout it all his life remained largely unchanged. Matt knew all too well that kingdoms rise and kingdoms fall, but that he had set his face to serve a different Kingdom, one shown him in 1884 when he confessed all and cast himself into the hands of the Living God.

By 1925, Matt was 69. He had been in poor health for some time. Out of necessity he tried to continue working as there was only limited relief for the poor or elderly, but his strength was failing. Nevertheless, he persisted in his prayer and penance. On 7 June 1925, whilst struggling down a Dublin alleyway on his way to Mass, he fell. A small crowd gathered around him. A Dominican priest was called from the nearby church, the one where Matt had been hurrying. The priest came and knelt over the fallen man. Realising what had happened, he lifted his hand in a blessing for the final journey. Little did he realise the dead stranger lying in front of him had already been on that ‘journey’ for over 40 years.

Having lived in the intimacy of the Triune God, it was apt Matt died on Trinity Sunday. Having lived off the Eucharist daily for more than 40 years, it was equally fitting he was buried on the feast of Corpus Christi.

Decades later, a visiting Italian priest went privately to pray at the grave of the Dublin worker he had heard so much about. In 1975, and after the due process had been completed, that same cleric, now Pope Paul VI, bestowed a new title upon that Irish workman: Venerable Matt Talbot.

There is a large trunk in the safe keeping of the Archdiocese of Dublin. It contains the books owned by Venerable Matt Talbot. A veritable treasury of spiritual theology, one of the books contained therein is True Devotion to Mary by St. Louis de Montfort. In its pages it reflects on being a slave to this world or to the Blessed Virgin. For those that choose the latter path it recommends, after due recourse to a spiritual director and the suitable enrolment, that a chain be worn to symbolise that that soul no longer belongs to the powers of darkness but is now a child of the light. On that June day in 1925, when Matt Talbot fell upon a Dublin street, it was dressed as a slave to Mary and as an ambassador of Christ.”

Love,

Matthew