Like so many of us, Caesar de Bus struggled with the decision about what to do with his life. After completing his Jesuit education he had difficulty settling between a military and a literary career. He wrote some plays but ultimately settled for life in the army and at court.

One of the glories of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, who proved to be one of the greatest catechists in the history of the Church. The seventh of thirteen children, he experienced a conversion from a worldly and frivolous life to embrace a life of prayer, penance, and austerity reminiscent of a St. Ignatius Loyola or a Pere de Foucald. He had been known as a dandy prone to cajolery and being “the life of the party” among his fellows.

For a time life was going rather smoothly for the engaging, well-to-do young Frenchman. He was confident he had made the right choice. That was until he saw firsthand the realities of battle, including the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacres of French Protestants in 1572.

-Le massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy, François Dubois (1529–1584), oil on panel, 94 × 154 cm (37 × 60.6 in), Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne, France, please click on the image for greater detail.

(The massacre took place five days after the wedding of the king’s sister Margaret to the Protestant Henry III of Navarre (the future Henry IV of France). This marriage was an occasion for which many of the most wealthy and prominent Huguenots had gathered in largely Catholic Paris.

The massacre began in the night of 23-24 August 1572 (the eve of the feast of Bartholomew the Apostle), two days after the attempted assassination of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, the military and political leader of the Huguenots. The king ordered the killing of a group of Huguenot leaders, including Coligny, and the slaughter spread throughout Paris. Lasting several weeks, the massacre expanded outward to other urban centres and the countryside. Modern estimates for the number of dead across France vary widely, from 5,000 to 30,000.

The massacre also marked a turning point in the French Wars of Religion. The Huguenot political movement was crippled by the loss of many of its prominent aristocratic leaders, as well as many re-conversions by the rank and file, and those who remained were increasingly radicalized. Though by no means unique, it “was the worst of the century’s religious massacres.” Throughout Europe, it “printed on Protestant minds the indelible conviction that Catholicism was a bloody and treacherous religion”.)

de Bus’s conversion took place on the way to a masked ball while passing by a place where a small light was burning before an image of the Blessed Virgin. Suddenly, the prayer of a remarkable unlettered friend, the mystic Antoinette Reveillade, came to mind. She had begged God with tears for the salvation of his soul that death would not find him in mortal sin.

He thought, “How can I recommend myself to God while I am on the way to offend Him?” An extraordinary grace was victorious. In the words of one of his biographers, “One tempestuous night, the All-powerful God, the King of Glory, encountered the worldly chevalier Cesar de Bus, obstinate in sin, and conquered him.”

He fell seriously ill and found himself reviewing his priorities, including his spiritual life. By the time he had recovered, Caesar had resolved to become a priest. Following his ordination in 1582, he undertook special pastoral work: teaching the catechism to ordinary people living in neglected, rural, out-of-the-way places. His efforts were badly needed and well received.

Ordained a priest in 1582, de Bus was profoundly affected by his reading a life of St. Charles Borromeo shortly after the saint’s death. He was to take him as a model in everything that seemed to suit his own temperament and formation best, that is, the penitential life of the holy cardinal, his devotion to the Passion of Christ, his preaching, and especially his catechetical apostolate imbued with a deep love of the Church undergoing the terrible after-shocks of the Protestant Revolution.

It should be recalled that the Blessed’s future catechetical apostolate was part of a vast movement of religious revival which implemented the decrees of the Council of Trent (1545-1563). One has only to think of the founder of the Jesuits, St. Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556), who died during the Council; St. Philip Neri, founder of the Oratory (1515-1575); St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582); St. John of the Cross (1542-1591); St. Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621); St. Peter Canisius (1521-1591); and particularly St. Charles Borromeo (1538-1584), the indefatigable Archbishop of Milan whose work with the famous Roman Catechism, provincial councils initiating needed reforms, and holiness of life, were to greatly influence the Blessed Cesar de Bus.

The French priest was to expend his energies catechizing the people of Aix-in-Provence who manifested massive religious ignorance as a result of the social and cultural turmoil stemming from the Religious Wars begun by Luther’s and Calvin’s rebellion. Largely forgotten today, de Bus was an impressive figure among his contemporaries. St. Francis de Sales considered him to be a holy rival to St. Philip Neri and declared him “a star of the first magnitude in the firmament of Catechesis.” De Bus was venerated by no less than Cardinal Richelieu who could not fail to be impressed by his austere and holy life.

Working with his cousin, Caesar developed a program of family catechesis. The goal—to ward off heresy among the people—met the approval of local bishops. Out of these efforts grew a new religious congregation: the Fathers of Christian Doctrine/”Prêtres séculiers de la doctrine chrétienne”.

One of Caesar’s works, Instructions for the Family on the Four Parts of the Roman Catechism/”Instructions familières”, was published 60 years after his death.

“I was so beside myself and fired with such a longing to do something in imitation of him, that I would not give my eyes sleep or my days rest until I had given some beginning to this resolution of mine.” -Blessed Cesar de Bus, writing about Saint Charles Borromeo

“In the year of his birth at Cavaillon, the Christian world is in a crisis, one of the most serious crises in its history. A crisis that is not only a religious and doctrinal one, but also a crisis of civilization, with the afflux of new movements of thought, not all negative, but which confuse the mass of the faithful. Cesar de Bus came into the world in this troubled period when men are gradually opening up to culture, to the arts and to the reign of pleasure. He let himself be swept along, during adolescence and early manhood, to the life of ease for which his social status and his fortune marked him out, the superficial, careless life of a gifted being, brilliant in society, a poet when he liked, more sensitive to the appeal of pleasure in every form than to the demands of the Gospel.

…After his conversion, the spiritual progress of the Blessed was not without its upsets, moments of discouragement, darkness and uncertainty. We have been struck, however, by what was to be, almost from the beginning, a characteristic of his whole life. Perhaps that is the secret of his constancy, or in any case, what always enabled him to overcome his difficulties and start off again with increased energy; we are referring to his “spirit of repentance.” Repentance is not an empty word for him. He carries it to its extreme consequences, for he has come back from afar! He must master the passion of which he was the slave in the past, a violent and perpetual battle against carnal temptations. He learns in this way to seek and love sacrifice, for sacrifice configures one with Christ Suffering and Victorious. To offer himself as a libation, to leave everything in God’s hand at the cost of the greatest renunciations, this seems to have been the leitmotif, the perpetual aim of his efforts. And when, at the end of his life, suffering and afflicted with blindness for 14 years, he is at last able to prepare for the supreme gift, he will realize how useful asceticism has been to master the old Adam. He will be ready to meet the Lord. His joy will be perfect.

The aim of Father de Bus is to communicate Christian doctrine to the people. The idea is far from being new. From the beginning the first Christians were anxious to transmit, and transmit exactly, the essential part of what they had received. Collections gathering the most outstanding events and sayings in the midst of a pagan world and in view of the dangers of doctrinal deviation, to inculcate in catechumens and recall to disciples a “kerygma,” that is, a central core, a “summary of the faith” containing the essential elements, which can serve as a basis for developments adapted to circumstances and to the psychology of listeners. It is necessary to give a solid foundation to their faith, to support their affective and charitable attachment to the living God with a knowledge of the truths of faith that will correspond to this love.

This is a period in which the world is in crisis, as formerly, and in which most values, even the most sacred ones, are rashly questioned in the name of freedom, so that many people have no longer any point of reference, in a period in which danger comes certainly not from an excess of dogmatism but rather from the dissolution of doctrine and the nebulousness of thought. It seems to Us that an additional effort should be courageously undertaken to give the Christian people, who are waiting for it more than is thought, a solid, exact catechetical base, easy to remember. We well understand that it is difficult today to adhere to the Faith, particularly for the young, a prey to so many uncertainites. They have the right at least to know precisely the message of Revelation, which is not the fruit of research, and to be the witnesses of a Church that lives by it.” -Pope Paul VI during the beatification of Blessed Cesar, April 27, 1975, “Christ to the World”, #4

“Blessed César de Bus, you who left us the admirable example of a life completely dedicated to God, you who were on fire with the desire to communicate the life of God to your brothers, intercede for us with the Lord now, so that the same fire may consume us and the same charity urge us.” -Pope Paul VI during the beatification of Blessed Cesar

Love,

Matthew

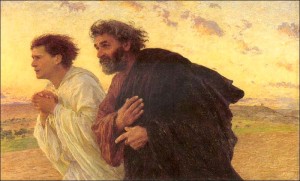

—“The Disciples Peter and John Running to the Sepulchre on the Morning of the Resurrection”, 1898, Eugène Burnand, please click on the image for greater detail

—“The Disciples Peter and John Running to the Sepulchre on the Morning of the Resurrection”, 1898, Eugène Burnand, please click on the image for greater detail![]()