Justification

-The Harrowing of Hell as depicted by Fra Angelico, 1441-1442, please click on the image for greater detail

-by Karlo Broussard

“One thing that divides Catholics and some Protestants is the understanding of justification, a theological term that’s generally used to signify a Christian being in a right relationship with God—meaning he is no longer subject to condemnation on account of sin.

The Council of Trent taught that “not only are we reputed [that is, considered “righteous” or “just” by God] but we are truly called and are just, receiving justice within us” (emphasis added). The late R.C. Sproul, however, denies the latter part of Trent’s teaching, stating, “It is not the change in our nature wrought by regeneration [Trent’s ‘justice within us’] or even the faith that flows from it that is the ground of our justification [being declared justified]. That remains solely the imputed righteousness of Christ.”

What Sproul is saying is that God considers Christ’s righteousness as our own (“the imputed righteousness of Christ”) and thereby declares us just, and that’s the only way we can consider ourselves just. Whatever interior change happens within us—a change from a state of ungodliness to a state of godliness—it plays no role in our justification. That interior change would be regeneration, which results in a state of sanctification, something that Protestants like Sproul see as essentially different from justification. No, we’re justified only on God’s say-so.

So how can we defend the Catholic Church’s teaching on justification as regeneration? In other words, how can we back up our insistence that the interior change that happens within us when we become Christians plays a role in us having a right relationship with God?

A full refutation of Sproul’s view would require us to do two things: 1) show that the Bible sees the interior change that is wrought by regeneration at least as grounds for our justification, even if not the only grounds, and 2) show that the grounds for our justification are not the imputed righteousness of Christ. This would suffice to refute Sproul’s claim. Further argumentation, however, would be needed to fully prove the Catholic position that the interior change wrought by regeneration (via sanctifying grace, given initially in baptism) is the sole ground for our justification, or what the Council of Trent called the “single formal cause.”

Due to the limited space that we have here, we’re going to focus only on the first of the two parts of our refutation of Sproul’s view. The passage to focus on is Romans 6:17-18:

But thanks be to God, that you who were once slaves of sin have become obedient from the heart to the standard of teaching to which you were committed, and, having been set free from sin, have become slaves of righteousness.

The first thing to note is that the Greek word for “righteousness” is dikaiosunē, which is related to the verb (dikaioō) that Paul uses throughout his letter to the Romans when he talks about Abraham “being justified [Greek, dikaioō] by faith” (Rom. 5:1; see also 4:2), a faith that God reckoned as “righteousness” (Greek, dikaiosunē—4:5). So, for Paul, the state of being “slaves of righteousness” is a state of being justified, like Abraham.

Now, according to Romans 5:1, the justification that we Christians have in Christ is another way of describing the “peace” that we have with God—again, a peace similar to what Abraham had with God. Paul writes, “Since we are justified by faith [like Abraham], we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

What does it mean to have “peace with God”? It means to be in a right relationship with him. It means we’re no longer subject to condemnation from him.

So the state of being “slaves of righteousness”—the state of justification—is a state of being at peace with God, or having a right relationship with him.

The next thing to note about the above passage is that Paul describes two states, both of which are preceded by and contrasted with the same state of slavery to sin. First, he speaks of becoming “obedient from the heart,” as opposed to being “slaves of sin.” Second, he speaks of “slaves of righteousness” who were “set free from sin”—which is to say his addressees went from being slaves of sin to being slaves of righteousness.

Given this “common denominator” of slavery to sin, it’s reasonable to conclude that Paul is describing in two different ways the same state that is opposite of being a slave to sin. This being the case, Paul doesn’t see a hard divide between the state of “obedience from the heart” and the state of being “slaves of righteousness.” In fact, he conceives of them as one and the same.

Here’s where the Catholic understanding of righteousness (the interior change wrought by regeneration) comes into play. Consider that obedience to God (“obedience from the heart”) entails the mind and the will being rightly ordered to God’s will—being disposed to believe as true what he says and to do what he commands. That’s an interior state, a state that’s constitutive of our character.

It’s this interior state of the heart and mind, a state that God brings about within us by grace, that Paul identifies as the state of being “slaves of righteousness,” which, as we saw above, is a state of justification, like that of Abraham. Therefore, interior righteousness at least is a ground for our justification.

This interpretation of associating the interior state of “obedience from the heart” with the state of being “slaves of righteousness” is further supported by verse 7 of this same chapter. Paul writes, “For he who has died [the death of baptism] is freed from sin.” The Greek verb for “freed” is dikaioō. So, the text can be literally translated as, “he who has died [the death of baptism] is justified from sin.”

Here, Paul explicitly ties this freedom from slavery to sin, which, as we saw above, is the interior state of “obedience from the heart,” to the state of being justified. It follows, therefore, that in Paul’s mind the state of being justified is not divorced from the interior state of “obedience from the heart,” a state where our hearts and minds are rightly ordered to God, or what the Council of Trent called the “justice within us.”

We can agree to some extent with those Protestants who, like Sproul, say that God declares us just. As Trent states, “not only are we reputed [righteous, or just] but we are truly called and are just”—the implication being that we can affirm that God reputes or declares us just. It’s just that, according to Paul, such a declaration corresponds to an objective reality: our interior state of righteousness that God brings about within us—what Paul calls “obedience from the heart.”

Again, as mentioned above, it takes further argumentation to establish that the interior state of righteousness constituted by sanctifying grace is the sole ground of our justification, or the “single formal cause.” But at least we can say that Paul doesn’t draw a hard divide between our state of being justified (being at peace with God and thus having a right relationship with him, whereby we are no longer subject to condemnation) and our interior state of being rightly ordered to God in obedience. In fact, he conceives of them as the same. And if that’s how Paul conceives of justification, then so should we.”

Love & His peace,

Matthew

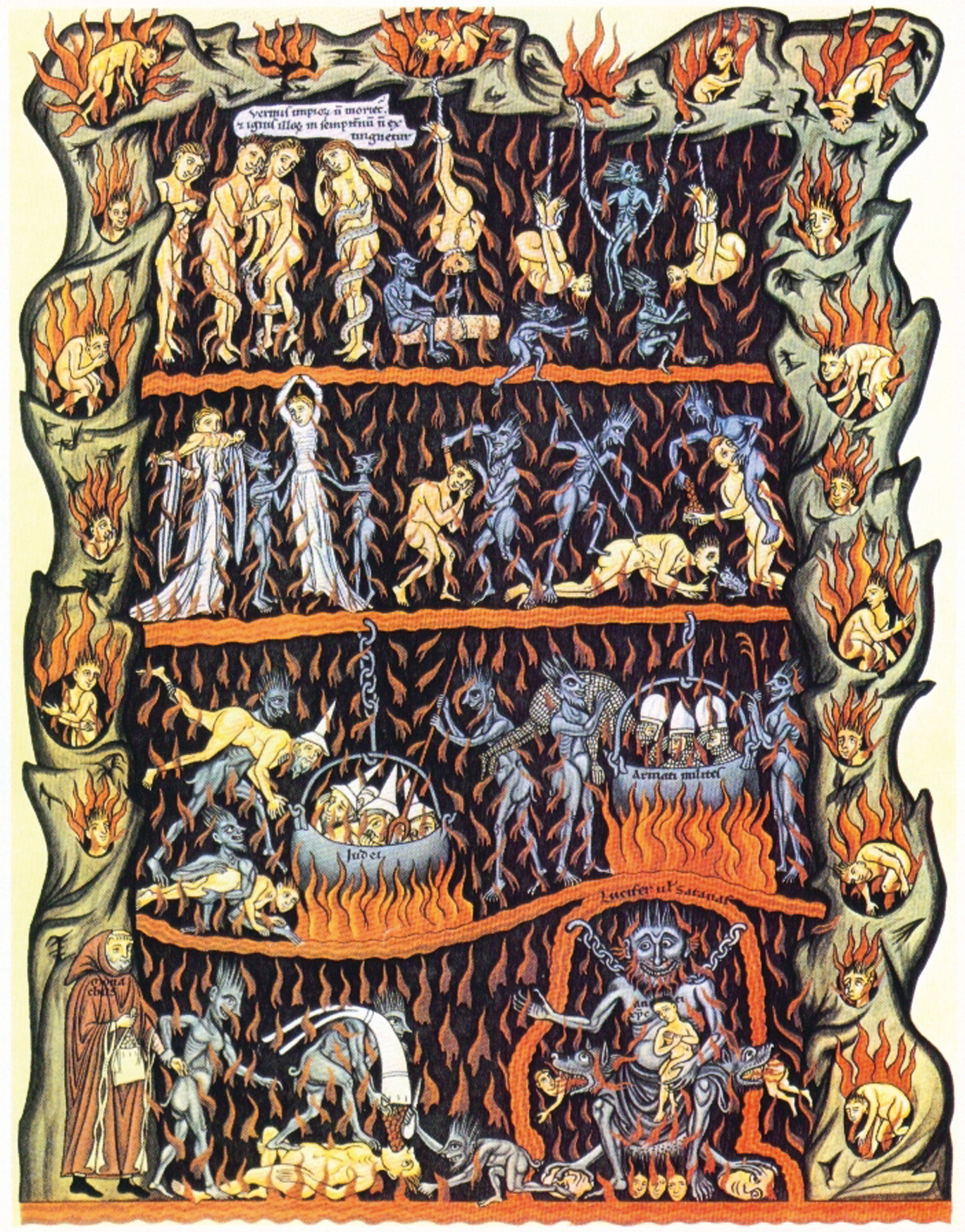

The Reality of Hell

-Medieval illustration of Hell in the Hortus deliciarum manuscript of Herrad of Landsberg (about 1180), please click on the image for greater detail

-by Pat Flynn

“The Catholic Church has condemned what is sometimes called strong or hard universalism, the idea that we know that everybody is saved. Perhaps weak or soft universalism may be true, which is to say, perhaps everybody, at the end of the day, just so happens to be saved, though it could have been otherwise. So far as I’m aware, Catholics can maintain the soft or weak (or hopeful) universalist view. Whether there are good reasons to is a debate I will not enter now.

On the other hand, there is “infernalism,” a pejorative term for the traditional doctrine of hell. But how can hell be compatible with an all-good God? Let’s see.

Some universalists suggest that hell is impossible because of infinite opportunities for people to repent. In other words, in some sort of war of attrition, God will inevitably win us over. But this ignores a classic position—namely, the postmortem fixity of the will. The idea is that we eternally separate from God and thus eternally will the consequences and punishments thereof. Thus, properly understood, hell is not an infinite consequence for a finite sin, but rather an eternal consequence for an eternal act (orientation) of the will.

In simple terms, the account of postmortem fixity is this: to change our minds, we must either come across new information or consider the information we have from a new perspective. But a traditional understanding of the human person maintains that neither of these conditions attains upon death, when the intellect is separated from the body. In effect, we “angelize” upon death, and the orientation of our will at that point remains thereafter. Nothing “new” or “different” is going to come along to get us to consider things afresh. Although God could perform a “spiritual lobotomy” on everybody who makes the faulty judgment of willing against Gain, God—in His perfectly wise governance—orders things toward their end in accord with their nature. And our nature is one of a fallible liberty—we are free, and we are free to make mistakes, which we do.

God is not going to constantly override our faulty (though culpable) judgments, as that would amount to the constant performance of something on the order of a miracle, which would make nonsense of generating nature (particularly human nature) to begin with. And God isn’t the business of nonsense.

In my experience of introducing the concept of postmortem fixity to universalists, several of them have not only seemed unaware of this traditional teaching, but responded by calling it “strange.” The teaching, however, is not strange; rather, it follows straightforwardly from a traditional metaphysical understanding of the human person, as Edward Feser explains in this lecture. It appears to be a highly probable, if not inevitable, consequence, of good philosophical analysis of the human person.

Now, I said that our nature is one of a fallible liberty, and this too is an important point. Only God (who is subsistent goodness itself) is his own rule; God alone is naturally impeccable, always perfect. Nothing else—neither man nor angel—is like this, and so every being of created liberty must be capable of failing to consider and subsequently apply the moral rule in every instance of judgment, and therefore be capable of sin. In other words, God could no more have created an infallible free creature than he could a square circle.

To appreciate this fact is to appreciate why God, if wanting to bring about creatures like us, necessarily brings about the possibility of our sinning and turning from him. In this sense, love—which requires the uniting of free independent wills—is inherently risky, especially when only one will (God’s) is incapable of sinning.

Now, if we apply the notions above—fallible liberty and postmortem fixity—to God’s mode of governance, we can see why God not only permits our moral failures in this life, but would continue to permit our moral failure to love him in the next life. God is under no obligation to override our moral miscalculation, even if he could. Nor is God any less perfect for not doing so, since it is a matter of Catholic dogma that everyone receives sufficient grace—that is, everything he needs to love God and reject sin. Nobody fails to love God because of what God doesn’t give him; people fail to love God because they indulge in voluntary and therefore culpable ignorance (that is, fail to consider what they habitually know, and really could consider), deciding instead to love some inferior good. If that is the final choice they make, God respects it.

Again, it is not enough for the universalist to dismiss these notions as seeming archaic or strange or what have you. The claim of many universalists, after all, is that universalism is necessarily true, but these notions show that that is not the case. If we have strong independent reason to think universalism is not true—say, from Scripture and Tradition—then all we need are possibilities (not certainties) for why God allows hell and its compatibility with God’s goodness. My suggestion is that a proper understanding of finite fallible liberty, God’s being a perfectly wise governor, and the possibility of the postmortem fixity of the will provide the necessary conceptual resources we need to show the compatibility between an all-good God and the doctrine of hell.

Let me address two other arguments. I’ve heard it said by universalists that God could not be perfectly joyful if anybody were in hell, but God is perfectly joyful; ergo, there can be no one in hell. But if this argument proves anything, it proves too much. After all, if God cannot be perfectly joyful if somebody is in hell, then how can God be perfectly joyful in light of any sin or evil? The answer, obviously, is that he cannot be, and so the position makes God dependent upon creation. If that’s the case, God is no longer really God , who should be in no way dependent upon creation for his perfection. So that argument is not a good one.

Finally, justice and punishment. Part of what motivates universalists are faulty (or at least non-traditional) notions of both. Traditionally, punishment, even eternal punishment, has been seen as itself a good, itself an act of mercy and justice. Boethius stressed this point strongly: it is objectively better for a perpetrator to be punished than to get away with his crime.

As put in The Consolation of Philosophy, “The wicked, therefore, at the time when they are punished, have some good added to them, that is, the penalty itself, which by reason of its justice is good; and in the same way, when they go without punishment, they have something further in them, the very impunity of their evil, which you have admitted is evil because of its injustice . . . Therefore the wicked granted unjust impunity are much less happy than those punished with just retribution.”

If Boethius is right, then hell could—perhaps even should—be seen as God extending the most love, mercy, goodness he can to someone in a self-imposed exile. Ultimately, what would be contrary to justice (giving one what he is due) would be for somebody to eternally reject God and get away with it.

PS: For an extended rebuttal of strong-form universalism, see my recent conversation with Fr. James Rooney.”

Love & His mercy,

Matthew

Invincible ignorance – Singulari Quadam

There is a “joke” that goes a missionary was evangelizing an indigenous native and the native asks ‘If I did not know about God and sin, would I go to hell?’ Priest: ‘No, not if you did not know.’ Native: ‘Then why did you tell me?’

Singulari Quadam

“2. Accordingly, We first of all declare that all Catholics have a sacred and inviolable duty, both in private and public life, to obey and firmly adhere to and fearlessly profess the principles of Christian truth enunciated by the teaching office of the Catholic Church…

3. These are fundamental principles: No matter what the Christian does, even in the realm of temporal goods, he cannot ignore the supernatural good. Rather, according to the dictates of Christian philosophy, he must order all things to the ultimate end, namely, the Highest Good. All his actions, insofar as they are morally either good or bad (that is to say, whether they agree or disagree with the natural and divine law), are subject to the judgment and judicial office of the Church.”

Summa Theologica Ia IIae q.76 a.2

“Extra ecclesiam nulla salus”

CCC 846 How are we to understand this affirmation, often repeated by the Church Fathers?335 Re-formulated positively, it means that all salvation comes from Christ the Head through the Church which is his Body:

Basing itself on Scripture and Tradition, the Council teaches that the Church, a pilgrim now on earth, is necessary for salvation: the one Christ is the mediator and the way of salvation; He is present to us in his body which is the Church.

He Himself explicitly asserted the necessity of faith and Baptism, and thereby affirmed at the same time the necessity of the Church which men enter through Baptism as through a door.

Hence they could not be saved who, knowing that the Catholic Church was founded as necessary by God through Christ, would refuse either to enter it or to remain in it.336

-by Joseph Heschmeyer, a former lawyer and seminarian, he blogs at Shameless Popery.

“In the beginning of the book of Isaiah, God declares, “Sons have I reared and brought up, but they have rebelled against me” (1:2). It’s a succinct description of the nature of sin: having seen the goodness of God, we have turned against Him in rebellion. But the person who does something wrong innocently and ignorantly isn’t a rebel; he’s just making a mistake. This idea—that for an evil to be a sin, it has to be chosen knowingly—is present from the first pages of Scripture. It’s not for nothing that the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden is from the “tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (Gen. 2:9). Prior to this kind of moral knowledge, you may act poorly, but it’s not sinful, just as it’s not sinful when a baby hits you and pulls your hair.

Of course, no one is totally ignorant. For instance, “no one is deemed to be ignorant of the principles of the moral law, which are written in the conscience of every man” (CCC 1860). You can’t murder your neighbor and pretend you had never heard that murder was wrong. But “ignorance of Christ and his gospel” (CCC 1792) certainly exists. How shall such people be judged? Jesus lays out the basic principle in Luke 12:48: “Every one to whom much is given, of him will much be required; and of him to whom men commit much they will demand the more.” Everyone has been given something (at least the principles of moral law), and we will be judged based on what we know or should have known, not on what we didn’t know.

Knowing the demands of the gospel means that you can’t claim “ignorance” of them on the Last Day. Of course, we can’t willfully stay ignorant of the gospel, since that’s the kind of “feigned ignorance” that actually makes our sin worse. But can’t we at least not preach the gospel so that other people can live and die in invincible ignorance?

Then-cardinal Joseph Ratzinger described his shock at hearing “a senior colleague” who “expressed the opinion that one should actually be grateful to God that he allows there to be so many unbelievers in good conscience. For if their eyes were opened and they became believers, they would not be capable, in this world of ours, of bearing the burden of faith with all its moral obligations. But as it is, since they can go another way in good conscience, they can still reach salvation.”

It’s not an exaggeration to say that this error is literally the anti-gospel. It treats the gospel (which literally means “good news”) as bad news from which we need to protect people, rather than good news that we need to share with the world. Logically, “faith would not make salvation easier but harder.” As the future Pope Benedict XVI observed, “in the last few decades, notions of this sort have discernibly crippled the disposition to evangelize. The one who sees the faith as a heavy burden or as a moral imposition is unable to invite others to believe.”

Where’s the actual error in reasoning in this anti-gospel? It’s in the assumption that those who have not heard of Jesus will live and die in invincible ignorance. Remember, “no one is deemed to be ignorant of the principles of the moral law, which are written in the conscience of every man” (CCC 1860). There are basic moral truths, including truths about the existence of God, that are knowable to everyone, even the desert islander who has never heard of Christianity or the Bible. And it would be dangerously naïve to assume that everyone has responded to even these limited glimpses of God’s revelation sufficiently to be saved. Contrast this naïve optimism with St. Paul’s description of paganism in Romans 1:18-21:

For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and wickedness of men who by their wickedness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. Ever since the creation of the world his invisible nature, namely, His eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse; for although they knew God they did not honor Him as God or give thanks to Him, but they became futile in their thinking and their senseless minds were darkened.

Paul knows that the pagans don’t know everything. They probably don’t know about the Torah or the moral law, or that there’s been a recent preacher in Galilee by the name of Jesus of Nazareth. But they do know (or at least should know) about certain truths about both morality and God’s “eternal power and deity.” And they responded to them, in large part, by “suppress[ing] the truth,” and choosing darkness over light. In short, the desert islanders who have never heard of Christ are in the same spot as the rest of us: God reveals truth to us, and we rebel and choose sin over him. It’s why Paul goes on to say that “all who have sinned without the Law will also perish without the Law, and all who have sinned under the Law will be judged by the Law” and that “there is no distinction; since all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom. 2:12, 3:22-23).

Everyone you meet—assuming he’s over the age of reason, and not counting serious mental disabilities and other extraordinary mitigating factors—is a sinner like you. Regardless of how much or how little God has revealed to him, he has chosen sin instead of God. If he has any self-awareness, he may even know this. To such people, the gospel isn’t a new burden. It’s the good news that their rebellion from God isn’t the end of the story and that a remedy exists, “through the redemption which is in Christ Jesus” (Rom. 3:24). The anti-gospel, rather than preserving people in a blissful state of innocent ignorance, rather damns them by leaving them with only their sin and not the cure.”

Love & truth,

Matthew

I look from afar – Aspiciens a longe

I look from afar:

and lo, I see the power of God coming,

and a cloud covering the whole earth.

Go ye out to meet Him and say:

Tell us, art Thou He that should come

to reign over Thy people Israel?

High and low, rich and poor, one with another.

Go ye out to meet Him and say:

Hear, O Thou shepherd of Israel, Thou that leadest Joseph like a sheep.

Tell us, art Thou He that should come?

Stir up Thy strength, O Lord, and come.

To reign over Thy people Israel.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost.

I look from afar:

and lo, I see the power of God coming,

and a cloud covering the whole earth.

Go ye out to meet Him and say:

Tell us, art Thou He that should come

to reign over Thy people Israel?

Save your soul: study the Trinity

-Most Holy & Undivided Trinity, detail from the altar of St Ignatius Loyola by Andrea Pozzo in the church of Il Gesù in Rome, please click on the image for greater detail

-by Br Bertrand Hebert, OP

“Augustine occupies a privileged place among the Western Church Fathers that Aquinas invokes. Despite their affinity, some have proposed a division between these great theologians. Augustine’s theology is often characterized as “affective” while Aquinas is labeled merely “rational.” This distinction is misleading in many ways, and it implies that Augustine’s theology lacks reason or that Aquinas’s theology is lifeless.

For both of these theological giants, affection and reason belong together. Theology is not just something nice to think about. It matters what you think, precisely because our salvation is mediated through the mysteries of the faith.

We can see this approach in both Augustine’s and Aquinas’s writings on the mystery of the Trinity. Bridging the “gap” between reason and affect, Trinitarian theology is both an intellectual and spiritual exercise. Augustine and Aquinas both modeled this, as Father Gilles Emery, O.P. explains in his essay “Trinitarian Theology as a Spiritual Exercise in Augustine and Aquinas.” Both Doctors show how understanding the complexity of man’s mind and heart reveals an intimate relationship between us who know and love and God who is the Knower and Lover. This theological investigation can be difficult; it “exercises” the soul in a real sense. But it also prepares the soul for communion with the Triune God whose very being is Truth and Love.

For Augustine, elucidating the mystery of the Trinity requires great mental effort, but it also demands devotion. Our efforts to understand God must be informed by love because “the more one loves God, the more one sees Him” (Emery, 7). Because we are seeking the most supreme truth in such an endeavor, our souls must be trained through a kind of “spiritual gymnastics.” This theological regimen strengthens us to rise to the heights to see God and is purified through prayer, penance, and a life of virtue. Moved by God’s grace, theological study prepares us to see God in a limited way in this life and propels us to behold Him in the beatific vision.

In his theology, Aquinas follows Augustine’s approach and builds on it. He delves into the mystery of the Trinity through speculative study, in order to enable believers to grasp the truth of God more deeply. Growing in knowledge of the Trinity both aids our contemplation and provides us with the means to defend the faith against error. Aquinas understands that by studying God, we come to recognize that our own knowing and loving is a mirroring of God Who is Knowing and Loving. This realization gives spiritual consolation to those who dwell in the darkness of this passing world, yearning for the light of the life to come.

As Augustine and Aquinas both demonstrate, true theology requires rational precision, but also an affective inclination to God. As the theologian—indeed any believer—rises to grasp the lofty mysteries of the Trinity he becomes ever more conformed to the God he seeks, and he receives already a foretaste of that vision he hopes to enjoy in glory.

Studying the Trinity stretches our minds. Theology that is both loving and rational lifts the soul in sacred study and puts one in contact with God. The shared theological approach of Augustine and Aquinas—integrating both reason and affection—is a model for teachers and students today. By seeking God through both wisdom and love, our deepest desire for God can be satisfied. God has made us for Himself, and both our hearts and minds are restless until they rest in Him (cf. St Augustine).”

Love,

Matthew

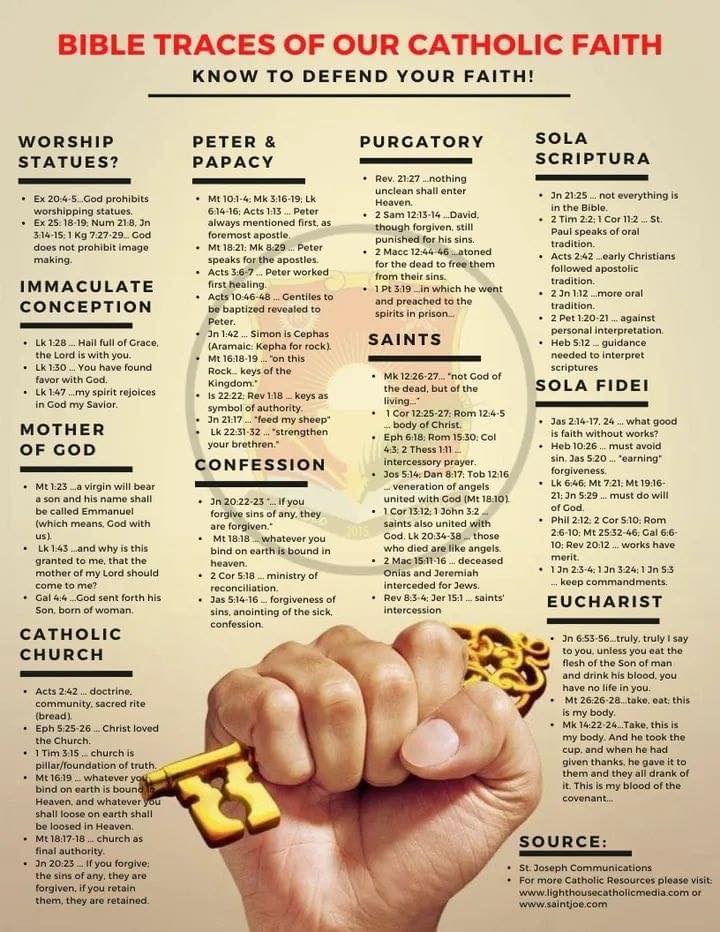

Catholics do not have to answer “Where is THAT in the Bible?”

-please click on the image for greater detail

-by Pat Flynn

“The other day, I tweeted something important: don’t forget to pray to your guardian angel. This received criticism from Protestants—for example, “Preferring to pray to an angel instead of to the one who commands them and is your Lord and Savior is cringeworthy.”Catholic users came in to clarify—Matthew 18:10, you know the drill. But here I want to say something different.

First, no Catholic thinks Scripture is the sole authoritative source to begin with, even if it is the highest authoritative source. Catholics also have Tradition and the Magisterium, and there we find the support we need for prayer to (that is, speaking to or asking for the intercession of) the angels. Catholics believe in a living, institutional, and hierarchical epistemic authority, which, according to the Faith, comes down to us by what is said: first, what is said by God eternally in His Son, the Logos, and from there what the Logos says to the apostles and then to the bishops, and right on down the line. This is the same authority that has given us the canon of Scripture, and having it is how we (as Catholics) can say, in a non-circular way, that this canon is the canon.

The Protestant position struggles seriously in this respect. After all, it seems as though sola scriptura—which is the operative rule for many Protestants—tells us we should not take as or make into doctrine anything that is not either explicitly taught in Scripture or clearly deducible from what is. The canon of Scripture itself must be a matter of doctrine for the Protestant, yet it is not something explicitly taught in Scripture or clearly deducible from what it is. It seems that the Protestant is committed to a contradiction in this matter. Nor does saying that sola scriptura is operative simply after the closing of the canon itself answer the pressing issue of how we reliably determine what the canon is or when it was closed, nor does Scripture indicate that such a paradigm shift is supposed to take place. Moreover, if the Church was able to reliably (that is, infallibly) guide us to the formation of the canon, it is contrived to then chop off that authoritative arm after the closing of the canon, especially since what counts as Scripture is only one of the epistemological issues facing sola scriptura—how to interpret Scripture and how to apply the lessons and consequences of Scripture in changing cultural contexts. Catholicism solves these issues with its expanded and more holistic notion of authority; Protestantism is refuted by them.

The other major point is this: the Protestant is frequently performing an illegitimate operation (i.e., often begging the question) by pushing the game onto his own turf when asking Catholics for this or that biblical proof text of his beliefs or practices—that is, by demanding that the Catholic play according to the rules of Protestantism. This is something Catholic convert Bryan Cross has pointed out various times: the question-begging assumption from Protestants that the Catholic magisterium’s understanding of faith and morals is no more authoritative than the understanding of any other Christian.

But the Catholic has every right to reject those “rules of engagement.” Why? Because the question is ultimately one of authority, not personal interpretation of biblical passages—which, we know, are often all over the place, not just between Catholics and Protestants, but among Protestants. If the Catholic view of authority is correct, and that authority substantiates prayer to the angels, then Catholics shouldn’t worry about proof-texting everything simply to cause the Protestant to think his beliefs and practices are less, as it were, cringeworthy. Whenever objections like these come up, the Catholic should highlight what the larger issue is; otherwise, the conversation runs the risk of being fruitless, since debates concerning biblical interpretation tend to go on endlessly with little to no productive resolution.

But maybe not entirely fruitless . . . as one can expose in such conversations many of the deeper issues inherent to the Protestant paradigm and sola scriptura in particular.

Apart from what has already been said, the Protestant position is frequently inconsistent, or at least conveniently lax in demanding the same standards of itself as it does Catholics. Returning to our example of prayer to angels, notice that the Protestant critic first demands biblical support for a position (asking angels for intercession), but then he gives a position that itself has no biblical support.

For example, our Protestant friend above tells us, “If Jesus’ instruction was a specific prayer and a model, then we would have ample reason to not veer off of that model unless we have equally comparable reason & authority to do so.” He continues, “The disagreement is that I’m stating that Jesus’ model does not allow for prayers to go to angelic beings, but rather should be directed to the Lord alone.”

But what is the biblical support for that? Specifically, what can we find in the Bible that tells us, either explicitly or through clear deduction, that if Jesus gives one model for prayer, then it is illegitimate to employ some other model unless we have equally comparable reason and authority to do so? (In asking what could constitute such an authority, this immediately puts the Catholic and Protestant right at the larger issue.) Or that Jesus’ model does not allow prayers to angelic beings just because it doesn’t include them? The answer is nothing—or at least nothing obvious.

Moreover, there is no teaching anywhere in Scripture that condemns speaking to angels. (Worshiping them is condemned, but that isn’t what Catholics are doing.) And just because Christ taught us to pray one way, there is no good biblical reason to say it is illegitimate to pray some other way. After all, Christ never prayed directly to the Holy Spirit. Ironically enough, I’ve heard Protestants claim that the apostles didn’t, either, and so (by extension) neither should we. But I know many Protestants who definitely do pray directly to the Holy Spirit. Either way, there is a claim being made that is not explicitly taught nor clearly deduced from Scripture, by somebody who demands that claims be substantiated by what is explicitly taught or clearly deduced from Scripture. What the Protestant is doing—if I dare say it—is putting out a tradition of man to reject what is the tradition of Christ’s Church.

And so the purpose of this article is not to defend, from a purely biblical perspective, prayers to angels. Various Catholics have already issued such defenses. (Joe Heschmeyer has a helpful article, and here’s Karlo Broussard on the intercession of saints in general.) Rather, the goal here is to point out the larger issues in these debates—issues that, I believe, expose several of the more fundamental incoherencies within the Protestant paradigm, while alerting Catholics to the fact they need not, and in fact should not, be pushed into debating according to the question-begging assumptions of the Protestant critic.”

Love,

Matthew

Self-defense

-by Karlo Broussard

“It’s immoral to kill an innocent human being. That’s because we all have a “right to life”—a moral claim on one another not to be killed.

But some might say that this approach creates a conflict with our general intuitions about justified lethal self-defense. Does the right to life extend even to an aggressor whose behavior will kill me (and I have no other means to effectively preserve my life)? It would seem so.

Think about it: if every human being has a right to life, and the aggressor is a human being, then the aggressor has a right to life. To deliberately kill him in self-defense, therefore, even if there is no other means of saving my life, would seem to be just as much a violation of justice as would be the deliberate killing of an innocent human person. And if that’s true, then it would be immoral to deliberately kill the aggressor.

For most of us, that doesn’t seem right. It runs contrary to our common intuitions. But long held intuitions are being washed away with the tides of modern thought—so we need to ground our intuition in something more stable. So why is it morally permissible to kill in self-defense?

We can start with an idea that we’ve looked at elsewhere: equality with other human beings in behavior that’s naturally consistent with the exercise of life, called the “equality of relations” (Summa Theologiae II-II:79:1), is naturally due to human beings. In other words, I owe it to you not to kill you—to be innocent in my behavior toward you. The same applies the other way around. St. Thomas Aquinas calls this the “equality of justice” (ibid).

Here’s where the rubber hits the road when it comes to self-defense. The obligation not to kill arises from an order of relationship that requires not only that we be innocent in will (what philosophers call “formal innocence”), but also that we be innocent in behavior (“material innocence”). When an aggressor attacks me with a behavior that by nature is going to kill me (even if the behavior is not voluntary, like in the case of a mentally crazed person), assuming that I didn’t attack him first, his behavior is no longer innocent. It has disrupted the equality in behavior that nature demands—in particular, the behavior that’s naturally consistent with the exercise of life. This being the case, the behavior is outside the order of the “equality of relations” that nature requires for the “equality of justice” and therefore is defective or disordered. How can I owe him anything then? The “equality of justice” rises or falls with the “equality of relations.”

Consider, for example, a father who tells his son, “Go into the store and steal me a beer!” Must the son obey? Absolutely not! Why? Because the father’s command is outside the proper order that nature requires for a father’s command—an order where the command directs his son to do good and avoid evil for his perfection as a human being.

And so, just as the son doesn’t owe obedience to the father’s disordered command, I don’t owe behavior that’s naturally consistent with the exercise of life as a response to the aggressor’s disordered act of aggression (an act of the kind that kills). In other words, it seems that I can defend myself by deliberately killing him without violating justice.

Not only does this seem so. It must be so. Why? To say otherwise would entail nature being defective with regard to necessary things. It would be self-defeating (Summa Contra Gentiles, 3.129).

Consider that if the aggressor’s right to life were so strong that I couldn’t kill him in the above scenario, nature would be practically safeguarding the aggressor’s behavior that thwarts the natural order for his life as a social animal. On this supposition, nature says that I can’t stop him. Remember: in this scenario there’s no other means for me to stop the behavior other than a lethal blow, and we’re assuming here that there’s no proper authority to turn to in the moment. And so there would be no one to stop the aggressor. That’s a self-defeating move: directing a human being to pursue his perfection as a social rational animal but also safeguarding him thwarting that perfection.

Also, the whole purpose of nature’s demand for another human being to refrain from killing me is to protect my life. If nature forbade me to kill the aggressor in the above scenario, then nature’s design would involve a space where there is no possibility for the protection of my life. That’s also self-defeating: setting out to protect my life while at the same time demanding that my life not be protected.

Someone might counter, “Well, there’s the possibility of proper authorities protecting your life.” But what if it’s those in authority who are trying to unjustly kill me? In this scenario, there would be literally no possible way to protect my life. My right to life would become a “duty to die.” And this would be due to nature’s design, which would be absurd.

Bottom line: it’s self-defeating for nature to give us a natural right we can’t protect. Philosopher Timothy Hsiao sums it up nicely: “If I possess the right to life, then I must also possess the corresponding right to secure or protect my life.”

Now, this doesn’t mean that I can kill an aggressor in any circumstance where his behavior violates the “equality of relations.” What I owe him (or don’t owe him) will depend on the degree of the inequality he creates with his attack.

For example, if the aggressor’s attack is such that it only limits my use of some good—e.g., he tries to steal my iPhone—I’m not thereby justified to kill him. The relation is unequal only with regard to the free use of personal goods—something that’s pretty far removed from the good of life. (Although it wouldn’t be just to kill him in order to get my iPhone back, it would be just to wrestle him to the ground [ST II-II:41:1].)

In other words, my defense must be proportionate to the inequality caused by the attack. As Aquinas puts it, “an act may be rendered unlawful, if it be out of proportion to the end” (ST II-II:64:7).

We started with the question, “Does the right to life extend even to an aggressor whose behavior lacks innocence to the degree that it’s not naturally consistent with the exercise of life?” As we’ve seen, human nature says no! The right to life extends only as far as nature allows it.

Nature sets boundaries that circumscribe a moral space in which another human being can rightly demand, in justice, that I not kill him—it’s a space of innocence, a space where there exists an equality of behavior that’s naturally consistent with the exercise of life. But those same boundaries reveal nature’s design for what I don’t owe the other person—namely, a duty to die.

So nature has given us a moral recipe for killing. Deliberately killing an innocent human being is an injustice, and therefore immoral. Deliberately killing an aggressor whose behavior will kill me, when there are no other means to preserve my life, is not an injustice—and, therefore, it’s morally permissible, and in some cases obligatory. Self-defense, therefore—even lethal self-defense—certainly can be compatible with the right to life.”

Love & truth,

Matthew

“Not My will…” -Mt 26:39b

-Martin Johann Schmidt (1718–1801), Christus am Ölberg, oil on canvas, 30.3 × 35.6 cm (11.9 × 14 in), private collection, Vienna, Austria, please click on the image for greater detail

My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from Me; yet, not as I will, but as You will. (Matt 26:39b)

“When Jesus prayed in the Garden of Gethsemane before His Passion, He renounced what He willed in obedience to the Father’s will. Yet this raises a question that the Church Fathers and Saint Thomas Aquinas attempted to resolve: How can Jesus, Who is God Himself and perfectly obedient to the Father, will anything as man that is opposed to the Father’s will? For if He did will anything of the sort, His human will would already be sinful for departing from God’s will. But if Christ did not have such a will, then it seems He could not renounce His will, as He clearly does.

To answer this question, Saint John Damascene, who adapted his thought from Saint Maximus the Confessor, distinguishes between thelesis and boulesis. He identifies thelesis as the natural power of willing that someone has. That power, to will something, has natural objects—such as, in the case of human beings, to live. Christ has a natural power of willing, and through that power he would ordinarily will to live.

According to Damascene, whereas thelesis describes the power to will something, boulesis describes what someone actually wills: that this person actually seeks to attain what he wills. Christ has a human power by which he naturally would will to live (thelesis), but instead he actually moves to obey the Father and submit himself to those who crucified him (boulesis).

The difficulty with this picture, however, is that Jesus would not be renouncing something he actually wills or desires. Rather, he’d merely be renouncing something that He could (and would normally) will. Thus, He in fact is renouncing no actual will at all.

For this reason, Aquinas reassigns the terms thelesis and boulesis. Neither of them refers to the power of willing this or that good. Rather, thelesis describes the act of willing an end—something that is good in itself. Yet, not everything that I wish for in this way moves me to do anything about it. That is, I do not intend every good end that I will. For instance, suppose I will to live for 175 years. Too bad. I might will that good in the sense that I wish for it, but I never intend it because there are no means that I can choose by which I can accomplish that end. Every act of thelesis is a wish, but not every such act is an intention accompanying a choice of means.

If thelesis describes the will for an end, boulesis describes the act of willing the means to an end. In order to bring about the end I will through thelesis, I will the means to that end through an act of boulesis—an act of choice. But, unlike thelesis, every act of boulesis involves the person moving himself to do something. Then, upon choosing the means, the prior act of thelesis for some good becomes not only a wish but also an intention.

Jesus in the garden actively wills (thelesis) to preserve his life because he naturally wishes for something that is good in itself. That is not against God’s will: God made us so that we would naturally wish for good things. But Christ also wills (thelesis) to be obedient to the Father and save the human race, which involves choosing (boulesis) to submit to suffering and death.

In this way, Christ’s will is in perfect conformity to the Father’s will, and he has a will that he renounces. Jesus wills (thelesis) to preserve his life. But he renounces it in the sense that he does not intend to preserve his life because that would involve choosing (boulesis) to reject the Father’s will—his will would move him against the Father. Instead, he intends to lovingly obey the Father (thelesis) by choosing (boulesis) to submit himself to the cross.

With this explanation, Aquinas gently adjusts the Fathers’ solution and opens up something of Jesus’ heart, making it a little easier for the rest of us to know Him and imitate His example of loving obedience to the Father.”

Love & truth,

Matthew

Preaching against sin

“We used to laugh at a famous story about President Calvin Coolidge, a man of few words. After returning from Sunday services, his wife asks him about the preacher’s sermon. “Sin,” Silent Cal replies. His wife pleads, “What did he say about it?” “He was against it.”

Alas, modern culture no longer allows us to oppose sin, except for those politically correct transgressions such as being “judgmental” and emitting too much carbon into the atmosphere. But do priests and others have a choice to remain faithful to Jesus?

There is an interesting correlation between our culture—including Catholic parishes—and our recognition of sin. It was easier to talk about the wages of evil in a stable culture imbued with Christianity. As secularism crowds out the influence of Christianity on culture, some Church authorities—in response to the hypersensitivities of many Catholics—place too many restrictions on preaching sin and conversion from the pulpit. Whiplash changes in the culture often challenge the prudence of thoughtful Catholic preachers.

A century ago, Church authorities, including moralists and seminary professors, were reticent in speaking—even reading—about sexual sin. The four-volume Moral and Pastoral Theology manual by Professor Henry Davis, S.J. (first edition, May 1935) illustrates pastoral prudence in questions of human sexuality. In an otherwise easy read (in English) on the natural law and the Ten Commandments, Davis writes the chapter dealing with various types of sexual sin in Latin. The readers must be priests or mature seminarians trained in the mother tongue of the Church for their preparation as confessors. But a good confessor, though he always avoids impure speech, must understand—and occasionally carefully discuss—lascivious behavior.

As the sexual revolution of the 1960s transformed popular culture, orthodox Catholic moralists relaxed the prudential censorship and discussed the details of many sexual sins to confront pervasive errors. Pope John Paul II’s “theology of the body” formed the foundation of John Paul II institutes on marriage and the family in Washington, D.C., and Rome. The institutes taught and wrote freely, providing the clergy and laity alike a firm foundation on the Church’s teaching on human sexuality.

Dissident moralists went farther. Human Sexuality, published by Anthony Kosnik in 1977 under the auspices of the Catholic Theological Society of America, justified sexual debauchery ranging from contraception and masturbation to sodomy and even bestiality. Today, senior prelates and friends of the pope openly speak about the likelihood of segments of the hierarchy approving “gay unions” soon. Several German bishops, including high-ranking ones, have declared their support of overhauling Catholic moral teaching to approve unions based on sodomy.

At the same time, many orthodox priests feel pressure to dodge these topics. They often avoid the issues not only from the pulpit, but also in church bulletins. Indeed, the culture and senior Catholic churchmen place us at a disadvantage. Irish bishop Ray Browne’s recent public apology for the sermons of Fr. Seán Sheehy on mortal sin is baffling, incomprehensible. Cross-dressed and occasionally mutilated males (so-called “transgender females”) conduct drag-show displays for children. As senior Catholic prelates call for gay unions, old-fashioned pastoral decorum prevents orthodox priests from asking obvious questions in the same public forums. (Here is an example of a forbidden question, with apologies to Latinists: An commercium ani vel fellatio vetatur post unionem gay agnitam vel ante tantum? Our moral manuals need an update.)

It is important to remember that the protection of the innocent must be a prime objective of every priest. Such conversations from the pulpit do risk violating Catholic prudence, especially with children present. Fr. John Hardon, S.J., refers in his Catholic Dictionary to the “latency period”: “The term mainly applies to the years between five and twelve, when children do not unless abnormally and unwisely aroused, react to sexual stimulation. The Church advises parents to cultivate this period for teaching children the principles of faith and training them in the moral habits they will need as the foundation of their adult Christian life.” So care is certainly called for and recklessness to be avoided.

Jesus is prudent but doesn’t mince words: “But I say to you, that whosoever shall look on a woman to lust after her, hath already committed adultery with her in his heart” (Matt. 5:28). St. Paul provides a similar perspective: “The men also, leaving the natural use of the women, have burned in their lusts one towards another, men with men working that which is filthy, and receiving in themselves the recompense which was due to their error” (Rom. 1:27). He adds, “For the things that are done by them in secret, it is a shame even to speak of” (Eph. 5:12). And he divorces Catholics from those who shamelessly promote willful debauchery: “But now I have written to you, not to keep company, if any man that is named a brother, be a fornicator, or covetous, or a server of idols, or a railer, or a drunkard, or an extortioner: with such a one, not so much as to eat” (1 Cor. 5:11).

Hence, the venues of preaching against sin determine the propriety of the language of Catholic morality. One size doesn’t fit all. What a moral textbook, theological article, scholarly monograph, episcopal encyclical, or even a popular internet piece permits may not be suitable from the pulpit. But carefully using Scripture as a rhetorical template accomplishes much.

So it seems that warnings against contraception, fornication, adultery, mutilation, and the gay agenda are well within the prudential rhetoric of Jesus in the Gospel and Paul in his letters. We need not expand the vocabulary to include the intimate details of sexual behavior. Indeed, for the most part, penitents in confession need not go beyond confessing such acts. The priest does not need to know—nor should he inquire about—the details.

But it is a great disservice and a violation of the Gospel for a priest to neglect the condemnation of sin, especially mortal sins that lead to the fires of hell. It’s always best to measure our rhetoric by the words of Jesus and the New Testament letters. Calvin Coolidge’s example of direct simplicity helps, too.”

Love & truth,

Matthew