-Roma Aeterna

Imho, the differences in some Protestant objections to Catholicism, as I have tried to plumb them, and Catholic rantings about Protestant ones, are often very minor nuances of terms? 🙁 I feel this is MORE tragic than if the contrast and the chasm were more stark, gross, and grievous. 🙁 Ut unum sint. Jn 17:21. And the devil giggles. 🙁

-from http://www.catholic.com/tracts/reward-and-merit

“Paul tells us: “For [God] will reward every man according to his works: to those who by perseverance in working good seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life. There will be . . . glory and honor and peace for every one who does good, the Jew first and also the Greek. For God shows no partiality” (Rom. 2:6–11; cf. Gal. 6:6–10).

In the second century, the technical Latin term for “merit” was introduced as a synonym for the Greek word for “reward.” Thus merit and reward are two sides of the same coin.

Protestants often misunderstand the Catholic teaching on merit, thinking that Catholics believe that one must do good works to come to God and be saved. This is exactly the opposite of what the Church teaches. The Council of Trent stressed: “[N]one of those things which precede justification, whether faith or works, merit the grace of justification; for if it is by grace, it is not now by works; otherwise, as the Apostle [Paul] says, grace is no more grace” (Decree on Justification 8, citing Rom. 11:6).

The Catholic Church teaches only Christ is capable of meriting in the strict sense—mere man cannot (Catechism of the Catholic Church 2007). The most merit humans can have is condign—when, under the impetus of God’s grace, they perform acts which please Him and which He has promised to reward (Rom. 2:6–11, Gal. 6:6–10). Thus God’s grace and His promise form the foundation for all human merit (CCC 2008).

Virtually all of this is agreed to by Protestants, who recognize that, under the impetus of God’s grace, Christians do perform acts which are pleasing to God and which God has promised to reward, meaning that they fit the definition of merit. When faced with this, Protestants are forced to admit the truth of the Catholic position—although, contrary to Paul’s command (2 Tim. 2:14), they may still dispute the terminology.

Thus the Lutheran Book of Concord admits: “We are not putting forward an empty quibble about the term ‘reward.’ . . . We grant that eternal life is a reward because it is something that is owed—not because of our merits [in the strict sense] but because of the promise [of God]. We have shown above that justification is strictly a gift of God; it is a thing promised. To this gift the promise of eternal life has been added” (p. 162).

The following passages illustrate what the Church Fathers had to say on the relationship between merit and grace.

Ignatius of Antioch

“Be pleasing to him whose soldiers you are, and whose pay you receive. May none of you be found to be a deserter. Let your baptism be your armament, your faith your helmet, your love your spear, your endurance your full suit of armor. Let your works be as your deposited withholdings, so that you may receive the back-pay which has accrued to you” (Letter to Polycarp 6:2 [A.D. 110]).

Justin Martyr

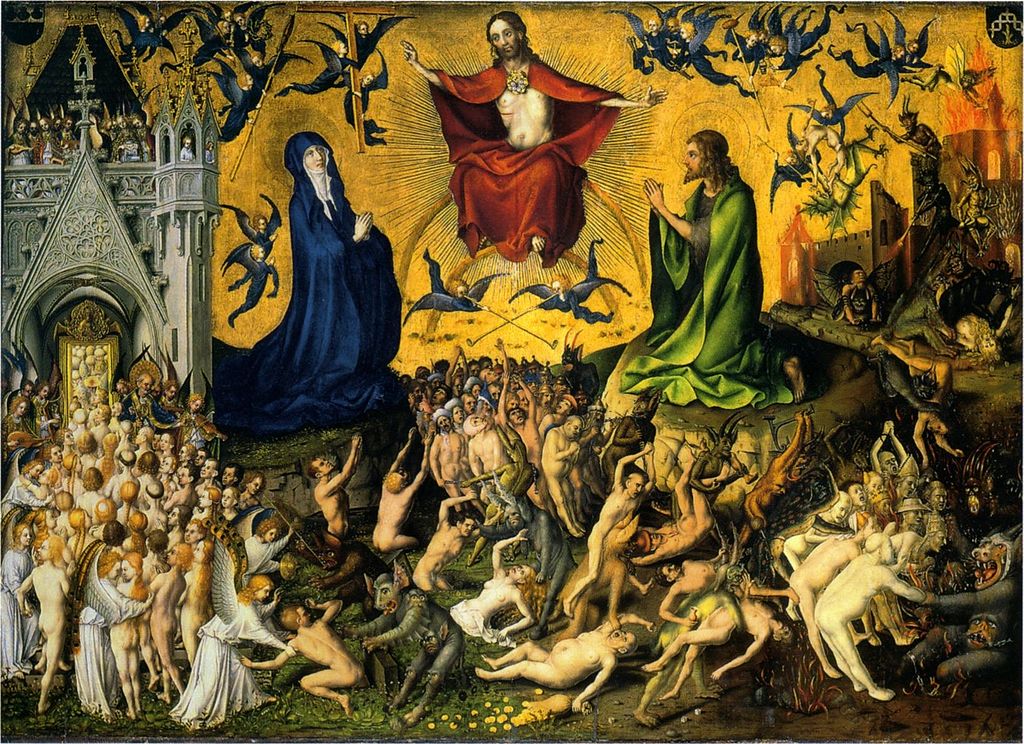

“We have learned from the prophets and we hold it as true that punishments and chastisements and good rewards are distributed according to the merit of each man’s actions. Were this not the case, and were all things to happen according to the decree of fate, there would be nothing at all in our power. If fate decrees that this man is to be good and that one wicked, then neither is the former to be praised nor the latter to be blamed” (First Apology 43 [A.D. 151]).

Tatian the Syrian

“[T]he wicked man is justly punished, having become depraved of himself; and the just man is worthy of praise for his honest deeds, since it was in his free choice that he did not transgress the will of God” (Address to the Greeks 7 [A.D. 170]).

Athenagoras

“And we shall make no mistake in saying, that the [goal] of an intelligent life and rational judgment, is to be occupied uninterruptedly with those objects to which the natural reason is chiefly and primarily adapted, and to delight unceasingly in the contemplation of Him Who Is, and of his decrees, notwithstanding that the majority of men, because they are affected too passionately and too violently by things below, pass through life without attaining this object. For . . . the examination relates to individuals, and the reward or punishment of lives ill or well spent is proportioned to the merit of each” (The Resurrection of the Dead 25 [A.D. 178]).

Theophilus of Antioch

“He who gave the mouth for speech and formed the ears for hearing and made eyes for seeing will examine everything and will judge justly, granting recompense to each according to merit. To those who seek immortality by the patient exercise of good works [Rom. 2:7], he will give everlasting life, joy, peace, rest, and all good things, which neither eye has seen nor ear has heard, nor has it entered into the heart of man [1 Cor. 2:9]. For the unbelievers and the contemptuous and for those who do not submit to the truth but assent to iniquity . . . there will be wrath and indignation [Rom. 2:8]” (To Autolycus 1:14 [A.D. 181]).

Irenaeus

“[Paul], an able wrestler, urges us on in the struggle for immortality, so that we may receive a crown and so that we may regard as a precious crown that which we acquire by our own struggle and which does not grow upon us spontaneously. . . . Those things which come to us spontaneously are not loved as much as those which are obtained by anxious care” (Against Heresies4:37:7 [A.D. 189]).

Tertullian

“Again, we [Christians] affirm that a judgment has been ordained by God according to the merits of every man” (To the Nations 19 [A.D. 195]).

“In former times the Jews enjoyed much of God’s favor, when the fathers of their race were noted for their righteousness and faith. So it was that as a people they flourished greatly, and their kingdom attained to a lofty eminence; and so highly blessed were they, that for their instruction God spoke to them in special revelations, pointing out to them beforehand how they should merit his favor and avoid his displeasure” (Apology 21 [A.D. 197]).

“A good deed has God for its debtor [cf. Prov. 19:17], just as also an evil one; for a judge is the rewarder in every case [cf. Rom. 13:3–4]” (Repentance 2:11 [A.D. 203]).

Hippolytus

“Standing before [Christ’s] judgment, all of them, men, angels, and demons, crying out in one voice, shall say: ‘Just is your judgment,’ and the justice of that cry will be apparent in the recompense made to each. To those who have done well, everlasting enjoyment shall be given; while to lovers of evil shall be given eternal punishment” (Against the Greeks 3 [A.D. 212]).

Cyprian of Carthage

“The Lord denounces [Christian evildoers], and says, ‘Many shall say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in your name, and in your name have cast out devils, and in your name done many wonderful works? And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from me, you who work iniquity’ [Matt. 7:21–23]. There is need of righteousness, that one may deserve well of God the Judge; we must obey his precepts and warnings, that our merits may receive their reward” (The Unity of the Catholic Church 15, 1st ed. [A.D. 251]).

“[Y]ou who are a matron rich and wealthy, anoint not your eyes with the antimony of the devil, but with the collyrium of Christ, so that you may at last come to see God, when you have merited before God both by your works and by your manner of living” (Works and Almsgivings 14 [A.D. 253]).

Lactantius

“Let every one train himself to righteousness, mold himself to self-restraint, prepare himself for the contest, equip himself for virtue . . . [and] in his uprightness acknowledge the true and only God, may cast away pleasures, by the attractions of which the lofty soul is depressed to the earth, may hold fast innocence, may be of service to as many as possible, may gain for himself incorruptible treasures by good works, that he may be able, with God for his judge, to gain for the merits of his virtue either the crown of faith, or the reward of immortality” (Epitome of the Divine Institutes 73 [A.D. 317]).

Cyril of Jerusalem

“The root of every good work is the hope of the resurrection, for the expectation of a reward nerves the soul to good work. Every laborer is prepared to endure the toils if he looks forward to the reward of these toils” (Catechetical Lectures 18:1 [A.D. 350]).

Jerome

“It is our task, according to our different virtues, to prepare for ourselves different rewards. . . . If we were all going to be equal in heaven it would be useless for us to humble ourselves here in order to have a greater place there. . . . Why should virgins persevere? Why should widows toil? Why should married women be content? Let us all sin, and after we repent we shall be the same as the apostles are!” (Against Jovinian 2:32 [A.D. 393]).

Augustine

“We are commanded to live righteously, and the reward is set before us of our meriting to live happily in eternity. But who is able to live righteously and do good works unless he has been justified by faith?” (Various Questions to Simplician 1:2:21 [A.D. 396]).

“He bestowed forgiveness; the crown he will pay out. Of forgiveness he is the donor; of the crown, he is the debtor. Why debtor? Did he receive something? . . . The Lord made himself a debtor not by receiving something but by promising something. One does not say to him, ‘Pay for what you received,’ but ‘Pay what you promised’” (Explanations of the Psalms 83:16 [A.D. 405]).

“What merits of his own has the saved to boast of when, if he were dealt with according to his merits, he would be nothing if not damned? Have the just then no merits at all? Of course they do, for they are the just. But they had no merits by which they were made just” (Letters 194:3:6 [A.D. 412]).

“What merit, then, does a man have before grace, by which he might receive grace, when our every good merit is produced in us only by grace and when God, crowning our merits, crowns nothing else but his own gifts to us?” (ibid., 194:5:19).

Prosper of Aquitaine

“Indeed, a man who has been justified, that is, who from impious has been made pious, since he had no antecedent good merit, receives a gift, by which gift he may also acquire merit. Thus, what was begun in him by Christ’s grace can also be augmented by the industry of his free choice, but never in the absence of God’s help, without which no one is able either to progress or to continue in doing good” (Responses on Behalf of Augustine 6 [A.D. 431]).

Sechnall of Ireland

“Hear, all you who love God, the holy merits of Patrick the bishop, a man blessed in Christ; how, for his good deeds, he is likened unto the angels, and, for his perfect life, he is comparable to the apostles” (Hymn in Praise of St. Patrick 1 [A.D. 444]).

Council of Orange II

“[G]race is preceded by no merits. A reward is due to good works, if they are performed, but grace, which is not due, precedes [good works], that they may be done” (Canons on grace 19 [A.D. 529]).

NIHIL OBSTAT: I have concluded that the materials

presented in this work are free of doctrinal or moral errors.

Bernadeane Carr, STL, Censor Librorum, August 10, 2004

IMPRIMATUR: In accord with 1983 CIC 827

permission to publish this work is hereby granted.

+Robert H. Brom, Bishop of San Diego, August 10, 2004″

Love,

Matthew