-by Peter Kreeft, PhD

“The argument from conscience, Romans 2: 14-16, is one of the only two arguments for the existence of God alluded to in Scripture, the other being the argument from design, Romans 1:18-20. Both arguments are essentially simple natural intuitions. Only when complex, artificial objections are made do these arguments begin to take on a complex appearance.

The simple, intuitive point of the argument from conscience is that everyone in the world knows, deep down, that he is absolutely obligated to be and do good, and this absolute obligation could come only from God. Thus everyone knows God, however obscurely, by this moral intuition, which we usually call conscience. Conscience is the voice of God in the soul.

Like all arguments for the existence of God, this one proves only a small part of what we know God to be by divine revelation. But this part is significantly more than the arguments from nature reveal about God because this argument has richer data, a richer starting point. Here we have inside information, so to speak: the very will of God speaking, however obscurely and whisperingly, however poorly heard, admitted, and heeded, in the depths of our souls. The arguments from nature begin with data that are like an author’s books; the argument from conscience begins with data that are more like talking with the author directly, live.

The only possible source of absolute authority is an absolutely perfect will.

Before beginning, we should define and clarify the key term conscience. The modern meaning tends to indicate a mere feeling that I did something wrong or am about to do something wrong. The traditional meaning in Catholic theology is the knowledge of what is right and wrong: intellect applied to morality. The meaning of conscience in the argument is knowledge and not just a feeling; but it is intuitive knowledge rather than rational or analytical knowledge, and it is first of all the knowledge that I must always do right and never wrong, the knowledge of my absolute obligation to goodness, all goodness: justice and charity and virtue and holiness; only in the second place is it the knowledge of which things are right and which things are wrong. This second-place knowledge is a knowledge of moral facts, while the first-place knowledge is a knowledge of my personal moral obligation, a knowledge of the moral law itself and its binding authority over my life. That knowledge forms the basis for the argument from conscience.

If anyone claims he simply does not have that knowledge, if anyone says he simply doesn’t see it, then the argument will not work for him. The question remains, however, whether he honestly doesn’t see it and really has no conscience (or a radically defective conscience) or whether he is repressing the knowledge he really has. Divine revelation (Ed. through Scripture) tells us that he is repressing the knowledge (Rom 1:18b; 2:15). In that case, what is needed before the rational, philosophical argument is some honest introspection to see the data. The data, conscience, is like a bag of gold buried in my backyard. If someone tells me it is there and that this proves some rich man buried it, I must first dig and find the treasure before I can infer anything more about the cause of the treasure’s existence. Before conscience can prove God to anyone, that person must admit the presence of the treasure of conscience in the backyard of his soul.

Nearly everyone will admit the premise, though. They will often explain it differently, interpret it differently, insist it has nothing to do with God. But that is exactly what the argument tries to show: that once you admit the premise of the authority of conscience, you must admit the conclusion of God. How does that work?

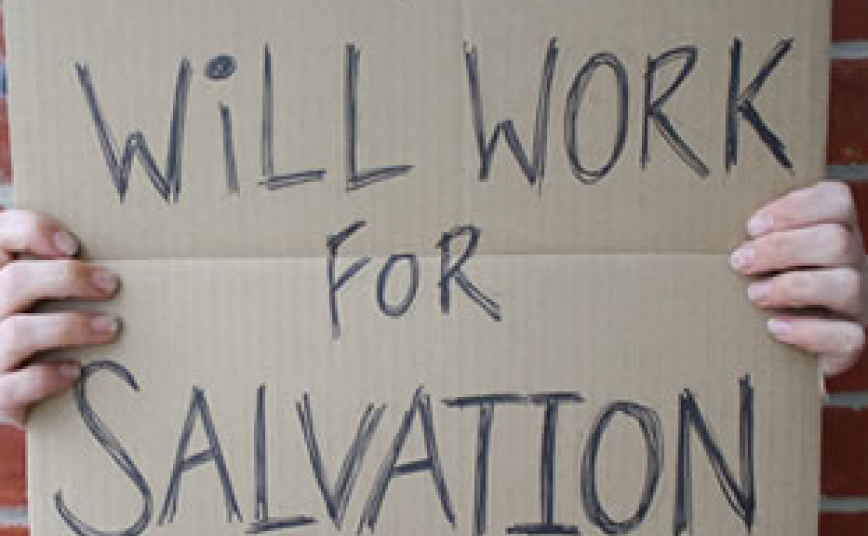

Conscience has an absolute authority over me.

Nearly everyone will admit not only the existence of conscience but also its authority. In this age of rebellion against and doubt about nearly every authority, in this age in which the very word authority has changed from a word of respect to a word of scorn, one authority remains: an individual’s conscience. Almost no one will say that one ought to sin against one’s conscience, disobey one’s conscience. Disobey the church, the state, parents, authority figures, but do not disobey your conscience. Thus people usually admit, though not usually in these words, the absolute moral authority and binding obligation of conscience.

Such people are usually surprised and pleased to find out that Saint Thomas Aquinas, of all people, agrees with them to such an extent that he says if a Catholic comes to believe the Church is in error in some essential, officially defined doctrine, it is a mortal sin against conscience, a sin of hypocrisy, for him to remain in the Church and call himself a Catholic, but only a venial sin against knowledge for him to leave the Church in honest but partly culpable error.

So one of the two premises of the argument is established: conscience has an absolute authority over me. The second premise is that the only possible source of absolute authority is an absolutely perfect will, a divine being. The conclusion follows that such a Being exists.

How would someone disagree with the second premise? By finding an alternative basis for conscience besides God. There are four such possibilities:

- something abstract and impersonal, like an idea;

- something concrete but less than human, something on the level of animal instinct;

- something on the human level but not divine; and

- something higher than the human level but not yet divine. In other words, we cover all the possibilities by looking at the abstract, the concrete-less-than-human, the concrete-human, and the concrete-more-than-human.

The first possibility, #1, means that the basis of conscience is a law without a lawgiver. We are obligated absolutely to an abstract ideal, a pattern of behavior. The question then comes up, where does this pattern exist? If it does not exist anywhere, how can a real person be under the authority of something unreal? How can more be subject to “less”? If, however, this pattern or idea exists in the minds of people, then what authority do they have to impose this idea of theirs on me? If the idea is only an idea, it has no personal will behind it; if it is only someone’s idea, it has only that someone behind it. In neither case do we have a sufficient basis for absolute, infallible, no-exceptions authority. But we already admitted that conscience has that authority, that no one should ever disobey his conscience.

The second possibility, #2, means that we trace conscience to a biological instinct. “We must love one another or die”, writes the poet W. H. Auden. We unconsciously know this, says the believer in this second possibility, just as animals unconsciously know that unless they behave in certain ways the species will not survive. That’s why animal mothers sacrifice for their children, and that’s a sufficient explanation for human altruism too. It’s the herd instinct.

The problem with that explanation is that it, like the first, does not account for the absoluteness of conscience’s authority. We believe we ought to disobey an instinct—any instinct—on some occasions. But we do not believe we ought ever to disobey our conscience. You should usually obey instincts like mother love, but not if it means keeping your son back from risking his life to save his country in a just and necessary defensive war, or if it means injustice and lack of charity to other mothers’ sons. There is no instinct that should always be obeyed. The instincts are like the keys on a piano (the illustration comes from C. S. Lewis); the moral law is like sheet music. Different notes are right at different times.

Furthermore, instinct fails to account not only for what we ought to do but also for what we do do. We don’t always follow instinct. Sometimes we follow the weaker instinct, as when we go to the aid of a victim even though we fear for our own safety. The herd instinct here is weaker than the instinct for self-preservation, but our conscience, like sheet music, tells us to play the weak note here rather than the strong one.

Honest introspection will reveal to anyone that conscience is not an instinct. When the alarm wakes you up early and you realize that you promised to help your friend this morning, your instincts pull you back to bed, but something quite different from your instincts tells you you should get out. Even if you feel two instincts pulling you (e.g., you are both hungry and tired), the conflict between those two instincts is quite different, and can be felt and known to be quite different, from the conflict between conscience and either or both of the instincts. Quite simply, conscience tells you that you ought to do or not do something, while instincts simply drive you to do or not do something. Instincts make something attractive or repulsive to your appetites, but conscience makes something obligatory to your choice, no matter how your appetites feel about it. Most people will admit this piece of obvious introspective data if they are honest. If they try to wriggle out of the argument at this point, leave them alone with the question, and if they are honest, they will confront the data when they are alone.

A third possibility, #3, is that other human beings (or society) are the source of the authority of conscience. That is the most popular belief, but it is also the weakest of all the four possibilities. For society does not mean something over and above other human beings, something like God, although many people treat society exactly like God, even in speech, almost lowering the voice to a whisper when the sacred name is mentioned. Society is simply other people like myself. What authority do they have over me? Are they always right? Must I never disobey them? What kind of blind status quo conservatism is this? Should a German have obeyed society in the Nazi era? To say society is the source of conscience is to say that when one prisoner becomes a thousand prisoners, they become the judge. It is to say that mere quantity gives absolute authority; that what the individual has in his soul is nothing, no authoritative conscience, but that what society (i.e., many individuals) has is. That is simply a logical impossibility, like thinking stones can think if only you have enough of them. (Some proponents of artificial intelligence believe exactly that kind of logical fallacy, by the way: that electrons and chips and chunks of metal can think if only you have enough of them in the right geometrical arrangements.)

The fourth possibility, #4, remains, that the source of conscience’s authority is something above me but not God. What could this be? Society is not above me, nor is instinct. An ideal? That is the first possibility we discussed. It looks as though there are simply no candidates in this area.

And that leaves us with God. Not just some sort of God, but the moral God of the Bible, the God at least of Judaism. Among all the ancient peoples, the Jews were the only ones who identified their God with the source of moral obligation. The gods of the pagans demanded ritual worship, inspired fear, designed the universe, or ruled over the events in human life, but none of them ever gave a Ten Commandments or said, “Be ye holy for I the Lord your God am holy.” The Jews saw the origin of nature and the origin of conscience as one, and Christians (and Muslims) have inherited this insight. The Jews’ claim to be God’s chosen people interprets the insight in the humblest possible way: as divine revelation, not human cleverness. But once revealed, the claim can be seen to be utterly logical.

To sum up the argument most simply and essentially, conscience has absolute, exceptionless, binding moral authority over us, demanding unqualified obedience. But only a perfectly good, righteous divine will has this authority and a right to absolute, exceptionless obedience. Therefore conscience is the voice of the will of God.

Of course, we do not always hear that voice aright. Our consciences can err. That is why the first obligation we have, in conscience, is to form our conscience by seeking the truth, especially the truth about whether this God has revealed to us clear moral maps (Scripture and Church). If so, whenever our conscience seems to tell us to disobey those maps, it is not working properly, and we can know that by conscience itself if only we remember that conscience is more than just immediate feeling. If our immediate feelings were the voice of God, we would have to be polytheists or else God would have to be schizophrenic.”

Love & truth,

Matthew

-Pope Francis kisses the feet of Muslim refugees during the foot-washing ritual at the Castelnuovo di Porto refugees center near Rome, Italy, March 24, 2016. Pope Francis on Thursday washed and kissed the feet of refugees, including three Muslim men, and condemned arms makers as partly responsible for Islamist militant attacks that killed at least 31 people in Brussels.

-Pope Francis kisses the feet of Muslim refugees during the foot-washing ritual at the Castelnuovo di Porto refugees center near Rome, Italy, March 24, 2016. Pope Francis on Thursday washed and kissed the feet of refugees, including three Muslim men, and condemned arms makers as partly responsible for Islamist militant attacks that killed at least 31 people in Brussels.