-1628 engraving, please click on the image for greater detail

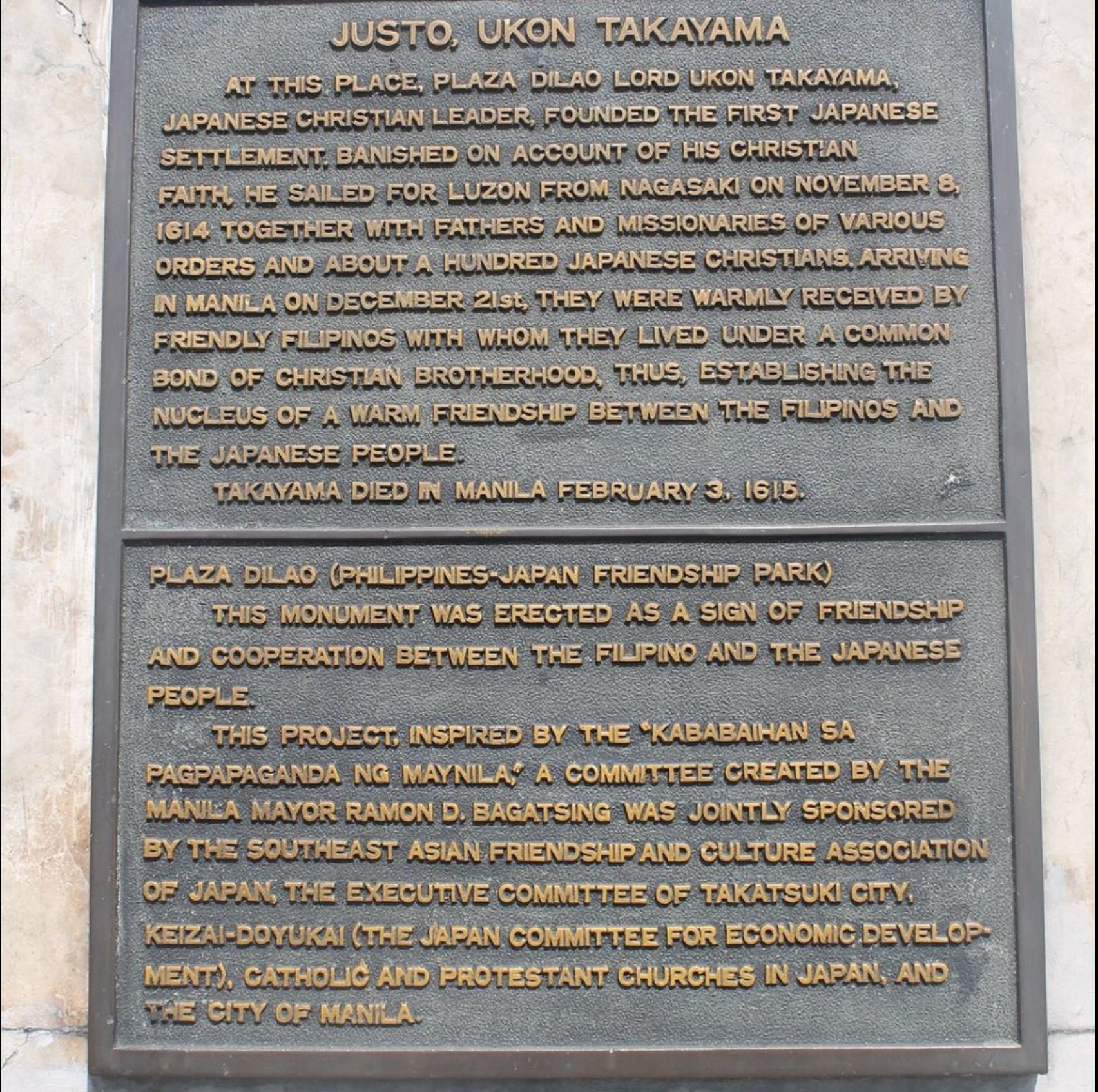

-monument to the 26 martyrs of Nagasaki, 1962, please click on the image for greater detail

With the Oscars last night, will Hollywood ever tell this story, instead of apostasy? I doubt it. One of the reasons I started this blog, to, in my own small way, tell the brilliance of saints. When Christian missionaries returned to Japan 250 years later, they found a community of “hidden Catholics” that had survived underground.

Jn 11:25

-by Matthew E. Bunson

“A group of twenty-six Christians gave their lives for Christ on a hill near Nagasaki, Japan, on February 5, 1597. They are noteworthy not only for the zeal they showed as they died as martyrs, but for the model they provided to Japanese Christians for centuries to come. Their story reminds us that heroic examples of the Catholic faith transcend country and race.

Jesuit Beginnings

The Catholic faith was introduced into Japan on August 15, 1549 by the great Jesuit missionary St. Francis Xavier, SJ, who landed on the Japanese island of Kyushu with two fellow Jesuits, Cosme de Torres, SJ, and John Fernandez, SJ. Francis soon learned of the prevailing political situation. Despite the emperor’s traditionally accepted divine origins, he had little authority; instead the local lords (daimyo) exercised extensive powers. Francis concentrated on winning the confidence of the daimyo in the area, and on September 29, he visited Shimazu Takahisa, the daimyo of Kagoshima, and asked for permission to build the first Catholic mission in Japan. The daimyo readily agreed to his request, believing that such a church might help to establish a trade relationship with Europe.

Francis mastered Japanese, then took his preaching into the neighboring island of Honshu, the main island in the Japanese archipelago. Within six years, six hundred Japanese converted to the faith in one province alone. But the rapid growth of the new faith soon provoked a sharp reaction. In 1561, the daimyo of several provinces launched a persecution that compelled Christians to abjure their faith.

Surprisingly, the Shogunate of Japan initially gave its support to the enterprise of evangelization. Primarily the shoguns believed the new religion might curb the influence of the sometimes-troublesome Buddhist monks in the islands, but they also thought it would facilitate trade with the outside world. Nevertheless, the Japanese officials were suspicious of the long-term intentions of the representatives of Spain and Portugal, most so because they were aware of the expanding Spanish Empire in Asia and the Pacific.

The labors of Francis Xavier were carried on and furthered by the Jesuit Alessandro Valignano, who arrived in 1579. This remarkable missionary opened a school to teach new mission workers, established seminaries, and promoted vocations for the Jesuits among the inhabitants. By around 1580, eighty missionaries were caring for more than one hundred fifty-thousand Christians, including the daimyo Arima Harunobu.

In Rome, Pope Gregory XIII declared his immense satisfaction with the work of the Jesuits and issued the decreed Ex Pastorale Officio in 1585. He declared that the Japanese missions were the exclusive territory of the Society of Jesus. Two years later, the first diocese was created at Funai (modern Oita).

-St Francisco Blanco OFM, Lima, Peru, please click on the image for greater detail”

Change in Politics

Several events soon transpired that changed the tolerant atmosphere. First, assorted Catholic missionaries who lacked the subtlety of the Jesuits arrived in Japan and failed to respect Pope Gregory’s decree. Their aggressive manner offended many Japanese, especially those who feared that Christianity was merely a prelude to invasion by the European powers. Thus, by 1587, when there were over 200,000 Christians in Japan, an initial edict of persecution was instituted by the country’s regent, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Nearly 150 churches were destroyed and missionaries were condemned to exile from the islands. The missionaries declined to leave and found safe haven in various parts of Japan. As a result of the persecution, within a decade the number of Christians had increased by 100,000.

The second major turning point occurred on August 26, 1596, when the San Felipe, a Spanish trade ship traveling from Manila to North America, ran aground off the coast of Shikoku, the southeastern island of Japan. Angered by the violation of Japanese territory, Hideyoshi ordered that the cargo be confiscated, and among the items seized were several cannons. The discovery alarmed Japanese officials, and the ship’s pilot made matters worse. Furious over the loss of his cargo, he threatened the Japanese with military action by Spain, an invasion, he claimed, that would be assisted by the Christian missionaries in the country.

The threats were complete fabrications, of course, but Hideyoshi used the occasion to seize the ship and then to launch the first major anti-Christian persecution in the history of Japan. In 1597, the same year as the arrival of the first bishop, Pierre Martinez, S.J., the government launched its pogrom. The Christian religion was banned, and those who refused to abjure the faith were to be condemned to death.

The initial public execution took place at Nagasaki, a city that had become the center of the Christian faith in Japan. The first martyrs were Paul Miki and his companions.

-drawing remembering 26 Catholic martyrs of Nagasaki, please click on the image for greater detail

Marked for Death

Born around 1564, Paul Miki was the son of a Japanese soldier, Miki Handayu. He was educated by the Jesuits and joined the Society of Jesus in 1580, the first Japanese to enter any religious order. Paul swiftly earned a reputation for the eloquence of his preaching. He was on the verge of ordination when he was arrested and thrown together with twenty-four other Catholics condemned to die in the name of the emperor. With Paul were six European Franciscan missionaries, two other Japanese Jesuits and sixteen Japanese laymen. The laymen included Cosmas Takeya, a sword maker; Paul Ibaraki, a member of a distinguished samurai family; and his brother Leo Karasumaru, who had been a Buddhist monk. Also arrested were Louis Ibaraki, twelve, a nephew of Paul Ibaraki and Leo Karasumaru; and thirteen-year-old Anthony of Nagasaki.

The martyrs were assembled at Kyoto, condemned to die, and then ordered to be taken to Nagasaki for their execution. As was customary, the prisoners had their left ears cut off prior to setting out so that they would be marked as condemned. The march to Nagasaki lasted a month. Along the way the men suffered the tortures of their captors and the jibes of crowds, but they also won the respect of many onlookers as they marched, bleeding and exhausted but still praying and singing. One Japanese Christian layman named Francis—a carpenter from Kyoto—decided to follow the martyrs as they progressed until he was arrested himself and expressed his joy at being included among them.

After the grueling trek from Kyoto, the condemned arrived at last at the place of their martyrdom, the city of Nagasaki. At ten in the morning on February 5, they were led along the highway from Tokitsu to Omura, and then commanded to stop at a small cluster of hills at the base of Mount Kompira. At the lowest of these hills, called Nishizaka, common criminals were put to death, and the lingering smell of rotting corpses could be detected. All was in readiness: Twenty-six crosses awaited the Christians.

Seeing the horrendous surroundings, several Portuguese merchants went to the brother of the governor, Terazawa Hazaburo, and asked him to intervene and at least have the place of execution moved. The governor, Ierazawa Hazaburo, was willing to listen to their plea, especially as his brother was a friend of Paul Miki. As it happened, across the road from the hill of Nishizaka was a lovely field of wheat, and the governor decreed that the executions could be carried out there.

-crucifixion of the martyrs of Nagasaki. A painting in the Franciscan convent of the Lady of the Snows in Prague, please click on the image for greater detail.

Calm amid Horror

At the wheat field, the martyrs were divided by the soldiers into three groups, each one headed by a Franciscan reciting the rosary. Each of the martyrs had his own cross, the wood cut to his height. Gonzalo Garcia, the forty-year-old Franciscan lay brother from India, was the first to be led to his cross. He was shown the instrument of his imminent death, and he knelt to kiss it. Today, he is venerated as the patron saint of Mumbai. Following his example, the martyrs one by one embraced the wooden crosses before them.

Unlike the Romans, the Japanese officials did not use nails. Instead, they fixed the martyrs to their crosses by iron rings around the neck, hands, and feet and ropes tightly binding the waist. The one exception was the Spanish Franciscan priest, Peter Bautista, Superior of the Franciscan Mission in Japan. This former ambassador from Spain (who had devoted his ministry for some years to lepers) stretched out his hands and instructed the executioners to use nails. Paul Miki, meanwhile, proved shorter than his cross had been measured. As his feet did not reach the lower rings, the executioners tied him down at the chest with rope and linens.

With their victims affixed, the soldiers and executioners simultaneously lifted the crosses. As history has demonstrated many times before and after, the crowd that had gathered for amusement at the expense of the dying fell silent as the large crosses thudded into the holes in the earth and the martyrs exhaled in agony from the jarring drop. On the hill with them were four thousand Catholics from Nagasaki. Young Anthony looked down and beheld his family at the front of the crowd, and he spoke words of hope to them.

Then, just as each had embraced his cross, the martyrs one by one began to sing hymns of praise, the Te Deum and the Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus. The victims struggled to sing and to raise their voices to God one last time. From his cross, Paul Miki also preached for the last time. Seeing the edict of death hanging from one soldier’s long, curved spear for all to see, he responded to the charge, his voice carrying across the hills:

I did not come from the Philippines. I am a Japanese by birth, and a brother of the Society of Jesus. I have committed no crime, and the only reason why I am put to death is that I have been teaching the doctrine of Our Lord Jesus Christ. I am very happy to die for such a cause, and see my death as a great blessing from the Lord. At this critical time, when you can rest assured that I will not try to deceive you, I want to stress and make it unmistakably clear that man can find no way to salvation other than the Christian way. (Luis Frois, Martyrs’ Records)

And then the martyrs began their final minutes. The first to die was the Mexican Franciscan Brother Philip de Jesus, who had also been measured incorrectly, so his entire weight was placed on the ring around his neck. He slowly choked to death, until the order was given for two soldiers to pierce his chest on either side with their spears. The soldiers, in pairs, thrust their spears into each side of the remaining victims until the blades literally crossed each other. Death was virtually instantaneous. The martyrs accepted their end with the same prayerful calm that marked their ascent upon the crosses. The gathered crowd, however, cried out in anguish, and the din could be heard in the city of Nagasaki below. Many Japanese who watched the horror unfold became Christians themselves in the coming weeks and months. For the soldiers, the scene proved too much, and many began to weep at the courage of the dead Christians, especially young Louis Ibaraki who cried out, “Jesus . . . Mary” with his last breath.

With the execution over, the Christians in the crowd surged forward to soak up the blood of the martyrs in cloths and to remove small pieces of clothing to preserve as relics. Driven away forcibly by the guards, the crowds slowly dispersed, turning back to see the last rays of the sun framing the twenty-six crosses in stark relief.

-Catholic martyrs of Nagasaki, please click on the image for greater detail

Love is Stronger than Death

After dark, more people gathered. Christians from Nagasaki arrived to pray for the martyrs. In the days following, thousands more made a pilgrimage to the site. Peasants, local daimyo, soldiers, and foreigners stopped at the hill and remained there transfixed in prayer or amazement until the guards forced them away. Word spread across Japan, and the example of the twenty-six martyrs became the rallying cry for Christians.

The people of Nagasaki christened Nishizaka the “Martyrs’ Hill.” The next year, an ambassador from the Philippines was given permission by Toyotomi Hideyoshi to gather up the remains and the crosses. Pilgrims continued to visit the site, and the best efforts of officials could not stop new visits, both public and clandestine.

Paul Miki and his Companions proved the first of many thousands of martyrs in the church of Japan. Sporadic persecutions were conducted over subsequent years, erupting in 1613 under the sharp campaign of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616), who considered Christianity to be detrimental to the good of Japan and the social order he was instituting. The next year, all missionaries were expelled and Japanese converts were commanded to abjure the faith. Long-simmering resentment against the persecutions culminated in a Christian uprising in 1637. This was mercilessly put down, and the once-flourishing Church in Japan seemed dead. Foreigners were forbidden to enter the country on pain of death.

The Church outside of Japan did not forget Paul Miki and his companions. The Twenty-Six Martyrs were beatified on September 15, 1627 under Pope Urban VIII, and they were canonized in 1862 by Pope Blessed Pius IX, making them the first canonized martyrs of the Far East. But then came a truly astonishing turn of events. In 1854, Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States arrived in Japan, and for the first time in two centuries, the country established official contact with the outside world. To the utter shock of Westerners, the Japanese Christians had not abandoned the faith despite brutal persecution. For two centuries, they had practiced the faith in secret. In 1865, priests from the Foreign Missions discovered twenty thousand Christians on the island of Kyushu alone. Religious liberty was at last granted in 1873 by the imperial government. What had sustained these Christians in the long dark years was their trust in Christ and the examples of those who had died for the faith. Foremost in their memory were the Twenty-Six Martyrs upon Nishizaka Hill.

Today, the site of the Twenty-Six Martyrs remains a beloved place of pilgrimage, and they are honored by the Monument of the 26 Martyrs erected in 1962, as well as a shrine and a museum. Thousands of visitors arrive every year. One of them, in 1981, was Pope John Paul II. He declared during his visit:

“On Nishizaka, on February 5, 1597, twenty-six martyrs testified to the power of the Cross; they were the first of a rich harvest of martyrs, for many more would subsequently hallow this ground with their suffering and death. . . . Today, I come to the Martyrs’ Hill to bear witness to the primacy of love in the world. In this holy place, people of all walks of life gave proof that love is stronger than death.”

Foreign Franciscan missionaries – Alcantarines

Saint Martin of the Ascension

Saint Pedro Bautista

Saint Philip of Jesus

Saint Francisco Blanco

Saint Francisco of Saint Michael

Saint Gundisalvus (Gonsalvo) Garcia

Japanese Franciscan tertiaries

Saint Antony Dainan

Saint Bonaventure of Miyako

Saint Cosmas Takeya

Saint Francisco of Nagasaki

Saint Francis Kichi

Saint Gabriel de Duisco

Saint Joachim Sakakibara

Saint John Kisaka

Saint Leo Karasumaru

Saint Louis Ibaraki

Saint Matthias of Miyako

Saint Michael Kozaki

Saint Paul Ibaraki

Saint Paul Suzuki

Saint Pedro Sukejiroo

Saint Thomas Kozaki

Saint Thomas Xico

Japanese Jesuits

Saint James Kisai

Saint John Soan de Goto

Saint Paul Miki

O God our Father, source of strength to all your saints, Who brought the holy martyrs of Japan through the suffering of the cross to the joys of life eternal: Grant that we, being encouraged by their example, may hold fast the faith we profess, even to death itself; through Jesus Christ our Lord, Who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Love of Him,

Matthew