-King Charles II, by John Michael Wright, 1600-1665

As the son of Queen Henrietta Maria, King Charles II was naturally imbued with Catholic sympathies; and the story of his deathbed, when Fr Huddleston brought the Blessed Sacrament to him from Queen Catherine of Braganza’s chapel, is well known.

Yet during the collective mania whipped up by Titus Oates under the pretense of a “Popish Plot” (1678-79), King Charles did little or nothing to save Catholics who found themselves in mortal peril. The only potential victims on whose behalf he intervened were the Queen and Louis XIV’s emissary Claude de la Colombière, SJ, of prior note.

Some 35 Catholics were executed, nearly all of them entirely innocent of treason. Of course, Charles was under intense pressure from skilful and unscrupulous politicians such as Lord Shaftesbury, who knew how to manipulate the mob.

The essential point, though, was that the Merry Monarch had no intention of going on his travels again. It is not easy to warm to the complacency with which he appeared to regard the deaths of so many falsely accused men.

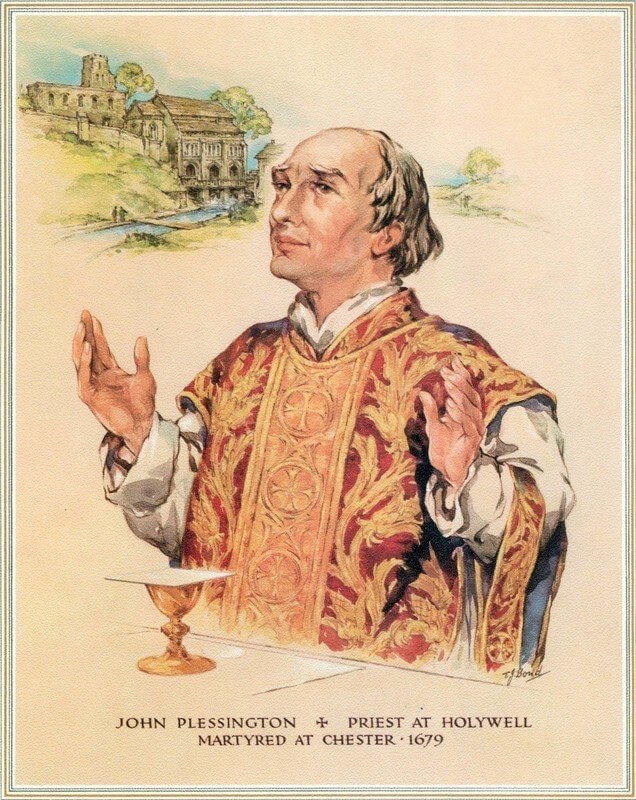

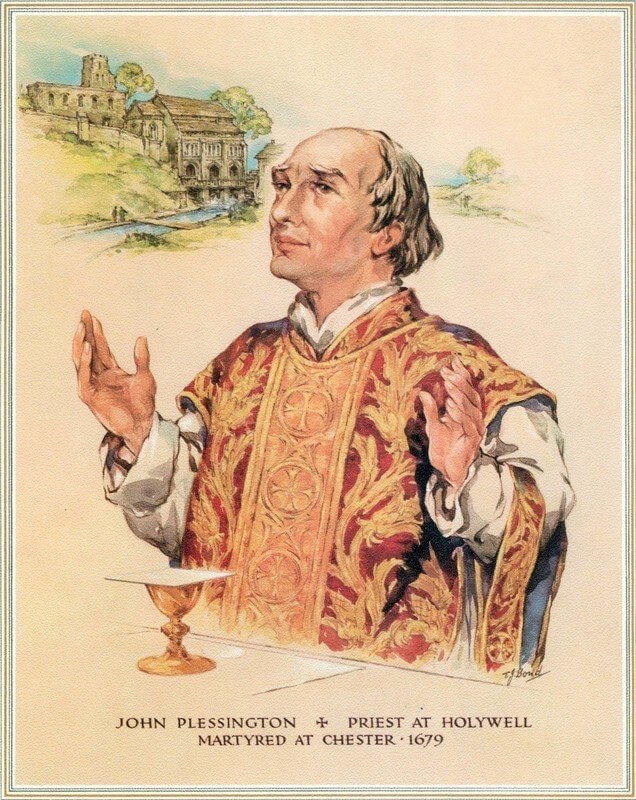

One of these was John Plessington. The youngest of three children, he was born in 1636 into a Catholic family at Dimples Hall, Garstang, near Preston in Lancashire. His father fought for the King in the Civil War and was taken prisoner.

John’s vocation may have been inspired by a family chaplain called Thomas Whitaker, who was captured and executed in 1646. At all events, Plessington, having attended the Jesuit school at Scarisbrick Hall, near Ormskirk, followed Whitaker in being educated at Saint-Omer and Valladolid. While abroad, he went under the name of William Scarisbrick. In 1662 he was ordained in Segovia. The next year, however, ill health brought him back to England.

For a while he served at the shrine of St Winifred in Holywell, North Wales. Then in 1670 he moved to Puddington Hall in the Wirral, as tutor to the Massey family.

For a while Plessington was able to minister openly to the local Catholic population. But when the scare of the Popish Plot extended to the north, a timeserver called Thomas Dutton collected a reward for arresting him.

There was no charge against Plessington, beyond his occupation as a Catholic priest, which sufficed for a death sentence. When the executioner came to measure him, Plessington joked that he was ordering his last suit.

According to a local tradition, St John was implicated at the insistence of a Protestant landowner simply because he had forbidden a match between his son and a Catholic heiress. Three witnesses gave false evidence of seeing St John serving as a priest: he forgave each of them by name from the scaffold.

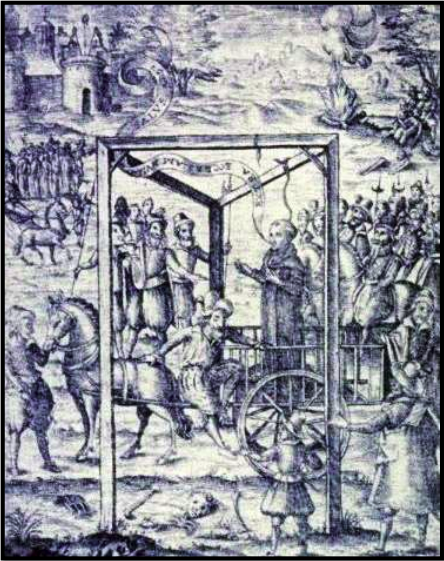

He was hanged, drawn and quartered in Chester on July 19 1679. His speech from the scaffold at Gallow’s Hill in Boughton, Cheshire was printed and distributed: He said: “Bear witness, good hearers, that I profess that I undoubtedly and firmly believe all the articles of the Roman Catholic faith, and for the truth of any of them, by the assistance of God, I am willing to die; and I had rather die than doubt of any point of faith taught by our holy mother the Roman Catholic Church…

I know it will be said that a priest ordayned by authority derived from the See of Rome is, by the Law of the Nation, to die as a Traytor, but if that be so what must become of all the Clergymen of the Church of England, for the first Church of England Bishops had their Ordination from those of the Church of Rome, or not at all, as appears by their own writers so that Ordination comes derivatively from those now living.”

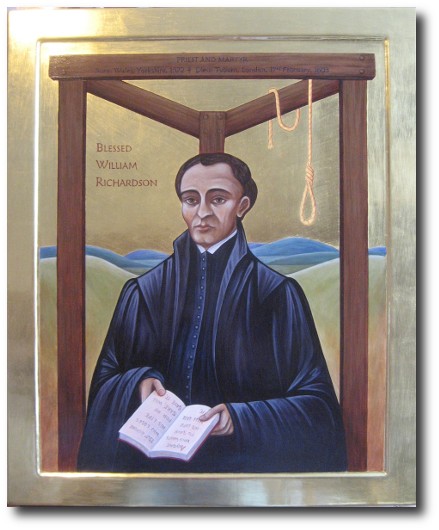

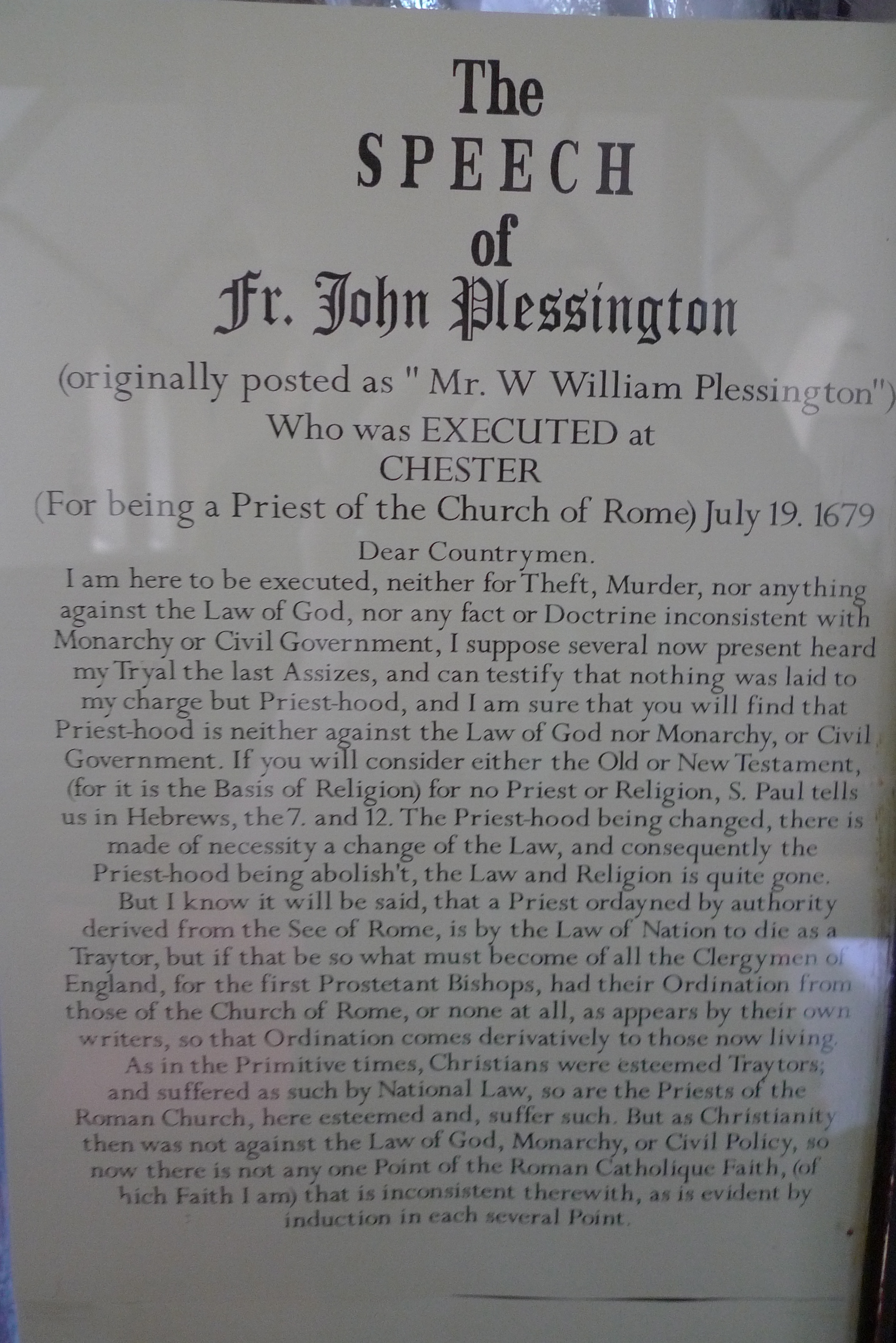

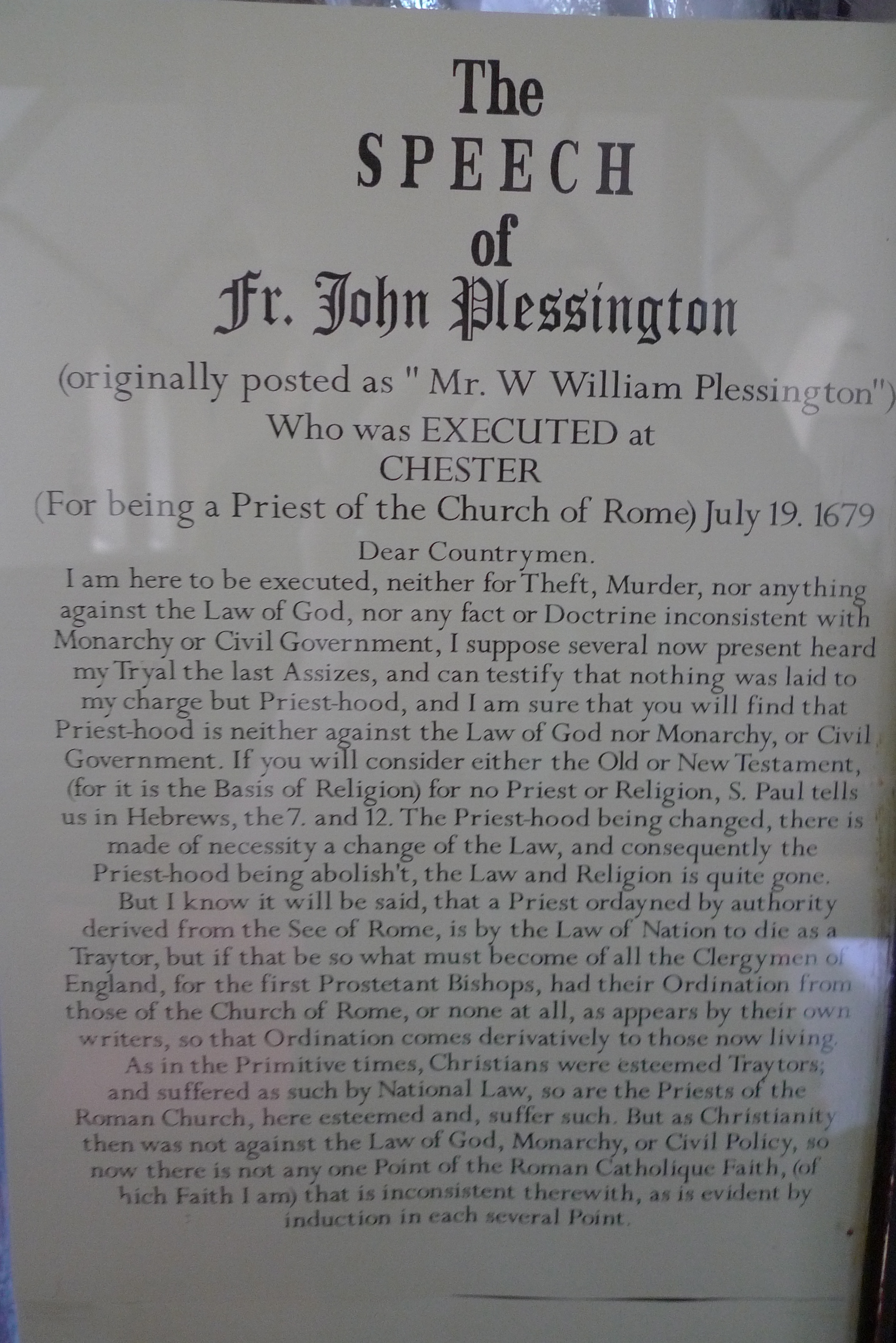

-displayed in St Winefride’s Church in Little Neston, on the Wirral, UK

“Dear Countrymen.

I am here to be executed, neither for Theft, Murder, nor anything against the Law of God, nor any fact or Doctrine inconsistent with Monarchy or Civil Government. I suppose several now present heard my trial the last Assizes, and can testify that nothing was laid to my charge but Priesthood, and I am sure that you will find that Priesthood is neither against the Law of God nor Monarchy, or Civil Government. If you will consider either the Old or New Testament (for it is the Basis of Religion […], St Paul tells us in Hebrews 7:12 that the Priesthood being changed, there is made of necessity a change of the Law, and consequently the Priesthood being abolished, the Law and Religion is quite gone.

But I know it will be said that a Priest ordained by authority derived from the See of Rome is by the Law of Nation to die as a Traitor, but if that be so what must become of all the Clergymen or England, for the first Protestant Bishops had their Ordination from those of the Church of Rome, or none at all, as appears by their own writers, so that Ordination comes derivatively to those now living.

As in the Primitive times, Christians were esteemed Traitors, and suffered as such by National Law, so are the Priests of the Roman Church here esteemed, and suffer such. But as Christianity then was not against the law of God, Monarchy or Civil Policy, so now there is not any one Point of the Roman Catholic Faith (of which Faith I am) that is inconsistent therewith, as is evident by induction in each several point.

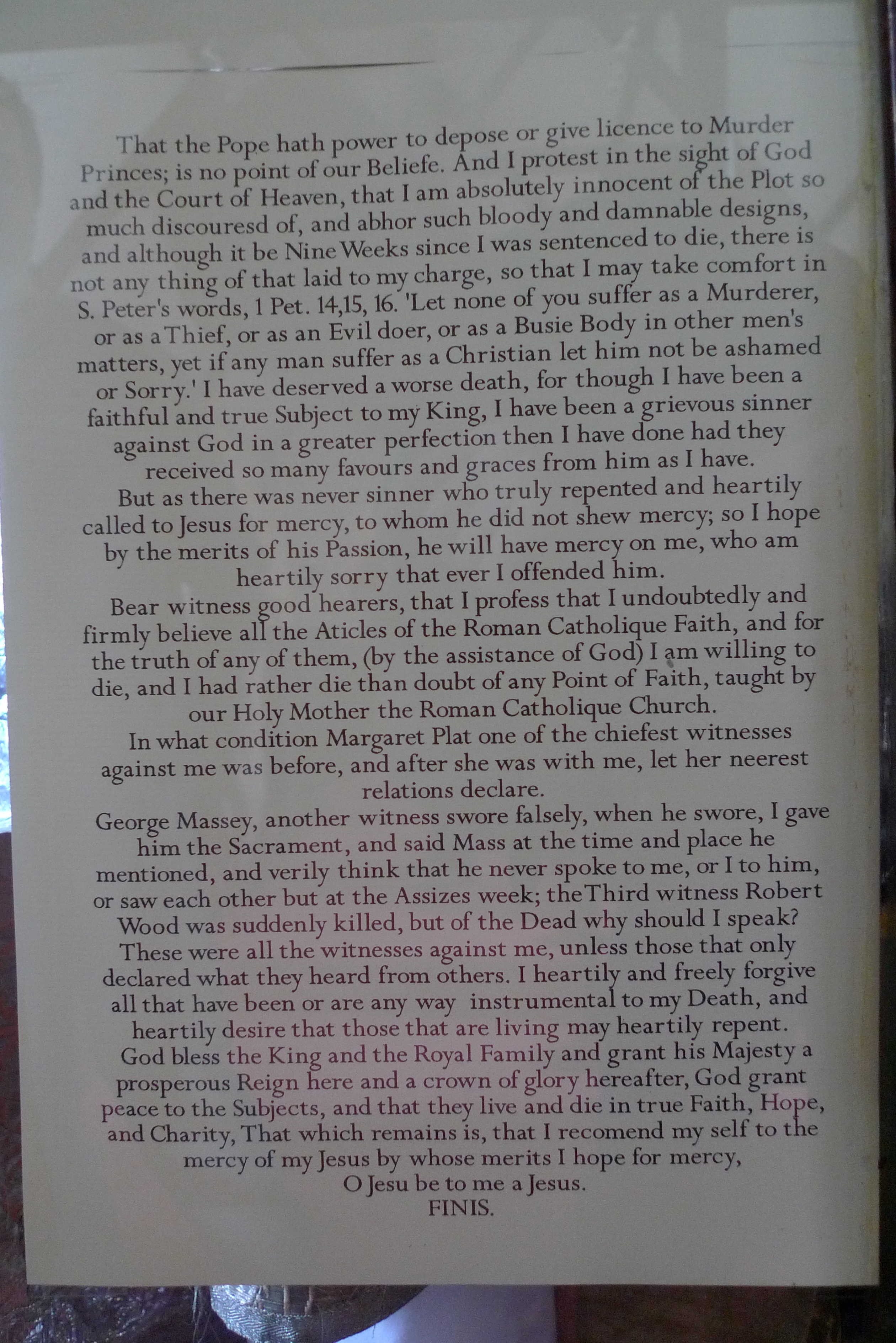

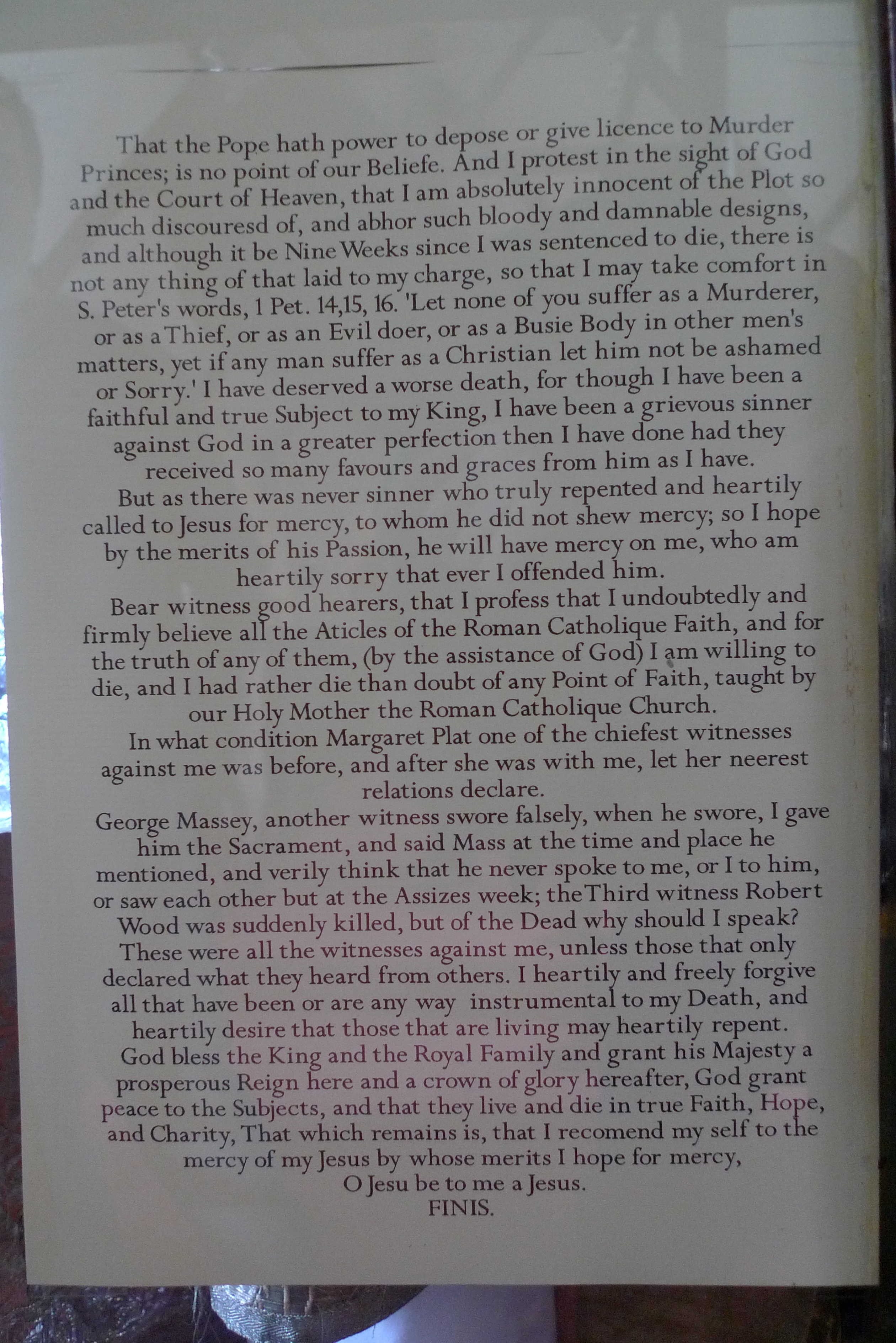

That the Pope hath power to depose or give licence to Murder Princes is no point of our Belief. And I protest in the sight of God and the Court of Heaven that I am absolutely innocent of the Plot so much discoursed of, and abhor such bloody and damnable designs. And although it be Nine Weeks since I was sentenced to die, there is not anything of that laid to my charge, so that I may take comfort in St. Peter’s words, 1 Peter 14-16, “Let none of you suffer as a Murderer, or as a Thief, or as an Evil doer, or as a Busy Body in other men’s matters, yet if any man suffer as a Christian let him not be ashamed or Sorry”. I have deserved a worse death, for though I have been a faithful and true Subject to my King, I have been a grievous sinner against God; [others would have lived] in a greater perfection [than] I have done had they received so many favours and graces from him as I have.

But as there was never sinner who truly repented and heartily called to Jesus for mercy, to whom he did not show mercy, so I hope by the merits of His Passion, He will have mercy on me, who am heartily sorry that ever I offended him.

Bear witness, good hearers, that I profess that I undoubtedly and firmly believe all the Articles of the Roman Catholic Faith, and for the truth of any of them (by the assistance of God) I am willing to die, and I had rather die than doubt of any Point of Faith, taught by our Holy Mother the Roman Catholic Church.

In what condition Margaret Plat one of the chiefest witnesses against me was before, and after she was with me, let her nearest relations declare. George Massey, another witness, swore falsely when he swore I gave him the Sacrament, and said Mass at the time and place he mentioned, and [I] verily think that he never spoke to me, or I to him, or saw each other but at the Assizes week. The third witness, Robert Wood, was suddenly killed, but of the Dead why should I speak? These were all the witnesses against me, unless those that only declared what they heard from others. I heartily and freely forgive all that have been or are any way instrumental to my Death, and heartily desire that those that are living may heartily repent.

God bless the King and the Royal Family and grant his Majesty a prosperous Reign here and a crown of glory hereafter, God grant peace to the Subjects, and that they live and die in true Faith, Hope, and Charity. That which remains is that I recommend my self to the mercy of Jesus, by whose merits I hope for mercy. O Jesus, be to me a Jesus.

FINIS*”

-St John Plessington

St John was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas’s, Burton, after Puddington locals would not allow his quarters to be displayed. Attempts to locate and exhume his body, as recent as 1962, have been unsuccessful but vestments associated with him are kept at St Winefride’s in Neston and a small piece of blood-stained linen is treasured as a relic in St Francis’s Church in Chester.

-a portion of skull with a large hole apparently cut from inside, being impaled by a pike from the inside out, a way of picking up a decapitated head without having to touch it – consistent with having been impaled on a spike after the person was beheaded.

It matched vertebrae from a neck which they concluded appeared to have been hacked off and a section of leg which linked to bone from a pelvis also bearing the marks of being cut.

Together, the report concluded, the presence of what appeared to be one of the quarters of a body and the fact that had been preserved in a Catholic context, as well as date of the clothing they were wrapped in meant they were almost certainly those of an executed priest.

-a lock of hair reputed to be from St John Plessington

https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/naming-the-unknown-martyr-could-these-remains-be-st-john-plessington-15408

Shrewsbury, England, Oct 14, 2015 / 02:03 pm ().-

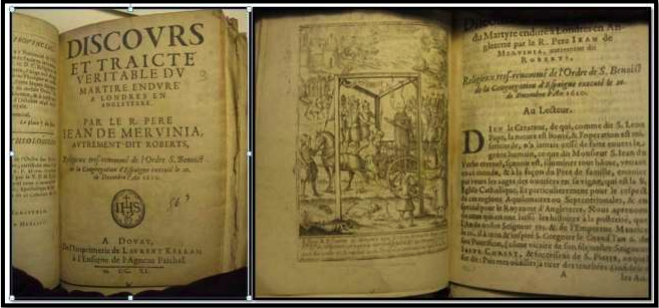

“…In the late 19th century bones were discovered hidden in a pub next to St Winefride’s Well in Flintshire, a Welsh county which borders on Chester. The location was a headquarters of Jesuit missionaries, though Plessington was not a Jesuit.

These bones were taken to the Jesuit retreat house of St. Beuno’s and venerated as the relics of an anonymous martyr.

Bishop Davies and others hope that DNA testing of the bones can be matched with known relics, to prove they are the remains of St. John Plessington.

Forensic scientists who examined the bones and said they are the skull and the right leg of a priest hanged, drawn and quartered. The skull has a hole punctured by a pike pushed through the head. The bones were found in a garment dated to the period of St. John Plessington’s execution.”

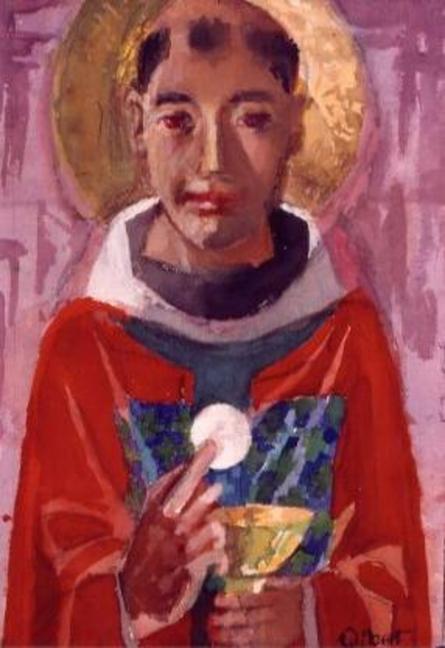

-stained glass window in St Winifrede’s Church Holywell depicting St John Plessington ministering to a kneeling woman and below with a group at his execution.

-St John’s vestments

Oh God, in Whom there is no change or shadow of alteration, You gave courage to the English Martyr, John Plessington. Grant unto us, we beseech You, through his intercession, the grace to always value the Holy Mass. May we be strengthened to serve You in imitation of the courageous heart of John Plessington and all the English Martyrs. We ask this through our Lord Jesus Christ, Your Son, Who lives and reigns with You in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Love,

Matthew

*Editorial Notes

In the first paragraph, the words “for no Priest or Religion” appear where the text above shows “[…]”. These words have been omitted here as the sense is not apparent. It seems likely that a line has been lost. By omitting the words, the sentence does make sense and it is hoped that it broadly conveys what Plessington was saying.

In the paragraph beginning “That the Pope” the words in the first square brackets have been added as this appears to convey the correct meaning of what is being said, and “then” changed to “than” as seems appropriate.

In the penultimate paragraph, the word “I” has been added, in square brackets, to make the meaning clearer.

Where spellings have an obvious modern equivalent, they have been updated as appropriate. Examples are “busy” for “busie” and “Catholic” for “Catholique”.

With these exceptions, the above wording faithfully records the document displayed in St Winefride’s Church in Little Neston, on the Wirral.

St John Plessington and all the Holy Martyrs of England and Wales, pray for us!