Jn 5:11

My mother, lovingly, and with the best of intentions for me, used to remind me, frequently, as a child, “The lightning is going to strike you, Mashew!!” Ostensibly, to keep the straight and narrow. And, “If my children lose their faith, I have failed as a mother!” NO PRESSURE!!!

There is a severity in Irish Catholicism, cf joyless Irish nuns of discipline, i.e. Our Lady of Perpetual Responsibility, Lake Wobegon, MN. Workhouses for Wayward Girls & Truant Boys, etc. I thought the Irish were tough, until I met the Polish in Chicago!! Jeesh!!! Did anyone else notice how the Polish jokes just stopped dead cold after JPII’s election? They did.

“…Why do they call this heartless place

Our Lady of Charity?

These bloodless brides of Jesus

If they had just once glimpsed their Groom

Then they’d know, and they’d drop the stones

Concealed behind their rosaries.

They wilt the grass they walk upon

They leech the light out of a room…”

-“Magdalene Laundries”, The Chieftains, Tears of Stone, 1999

-Cornelius Jansen (1585–1638), professor at the Old University of Louvain, painting by by Evêque d’Ypres

The heresy of Jansenism is named after Cornelius Jansen, who was the Bishop of Ypres in the early 17th century. His main work, Augustinus, was published after his death. In this work, he claimed to have rediscovered the true teaching of St. Augustine concerning grace, which had been lost to the Church for centuries. Even though he was not strictly a heretic, his writings still caused great harm to the Church.

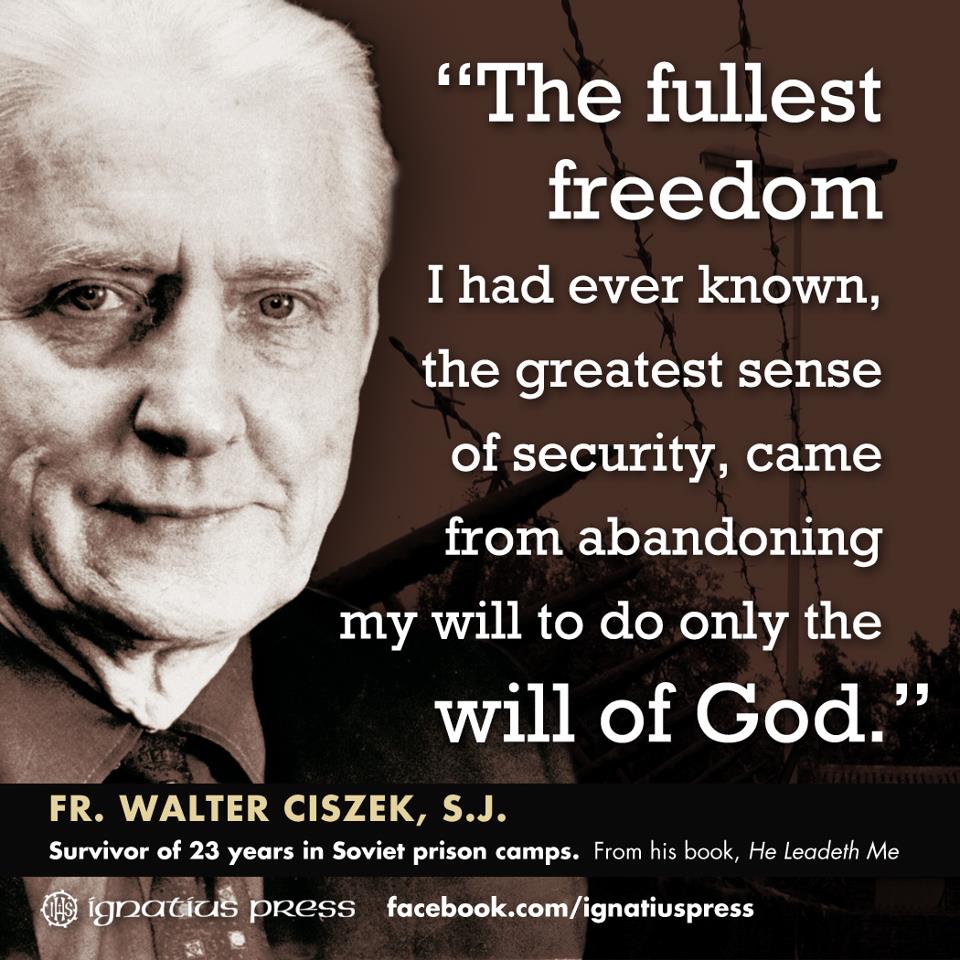

At that time, the Jesuits were heavily preaching on the mercy of God. This was seen by some as moral laxity. Also the debates with the Calvinists had an influence on Jansen’s thoughts. Without going into the details of the “five propositions from Jansen”, this heresy essentially taught that God’s saving grace is irresistible, though not given to everyone. According to Jansen, a person could neither accept or reject this grace due to his fallen nature. Although persons, who received it, were sure of salvation. Unfortunately not everyone received this saving grace. God decreed who was saved and who was lost. Jansen denied human free will and God’s desire to save everyone (1 Tim. 2:4). Even though the Jansenists hoped to combat the moral laxity of their time through moral rigorism, their denial of human free will and God’s mercy actually promoted moral despair or a carefree, frivolous life style, since personal actions had no effect on personal salvation. Due to the duplicity of its promoters, this heresy harmed the Church for over seventy years.

Summary of Catholic Teaching on Grace & Free Will:

1) The grace merited by Christ is necessary for us for all actions of piety and the exercise of every virtue and should be asked of from God.

2) With the help of grace, all the commandments of God are possible to obey, such that a chaste and holy Christian life without mortal sin is possible. Also, without this grace, we cannot do anything that is truly good, nor even persevere in good except by grace.

3) Grace prevents and aids our wills in such a way that we owe our salvation to God’s grace; if we do fall, it should be imputed to ourselves.

4) Grace strengthens and supplements our freedom, but in no way destroys it.

5) While maintaining the existence and freedom of the will, we should nevertheless remain in a posture of humility, remembering that our will is aided by grace in ways we don’t understand.

I have been trained as a catechist that the Truth, which the Church seeks, is often found in a middle course, a middle way between extremes. This is NOT splitting the difference!!! But, rather, a sincere search for and discovery of the Truth of God. The fact of the matter is, I have been trained, is that Truth happens to often be found in the moderation of extremes.

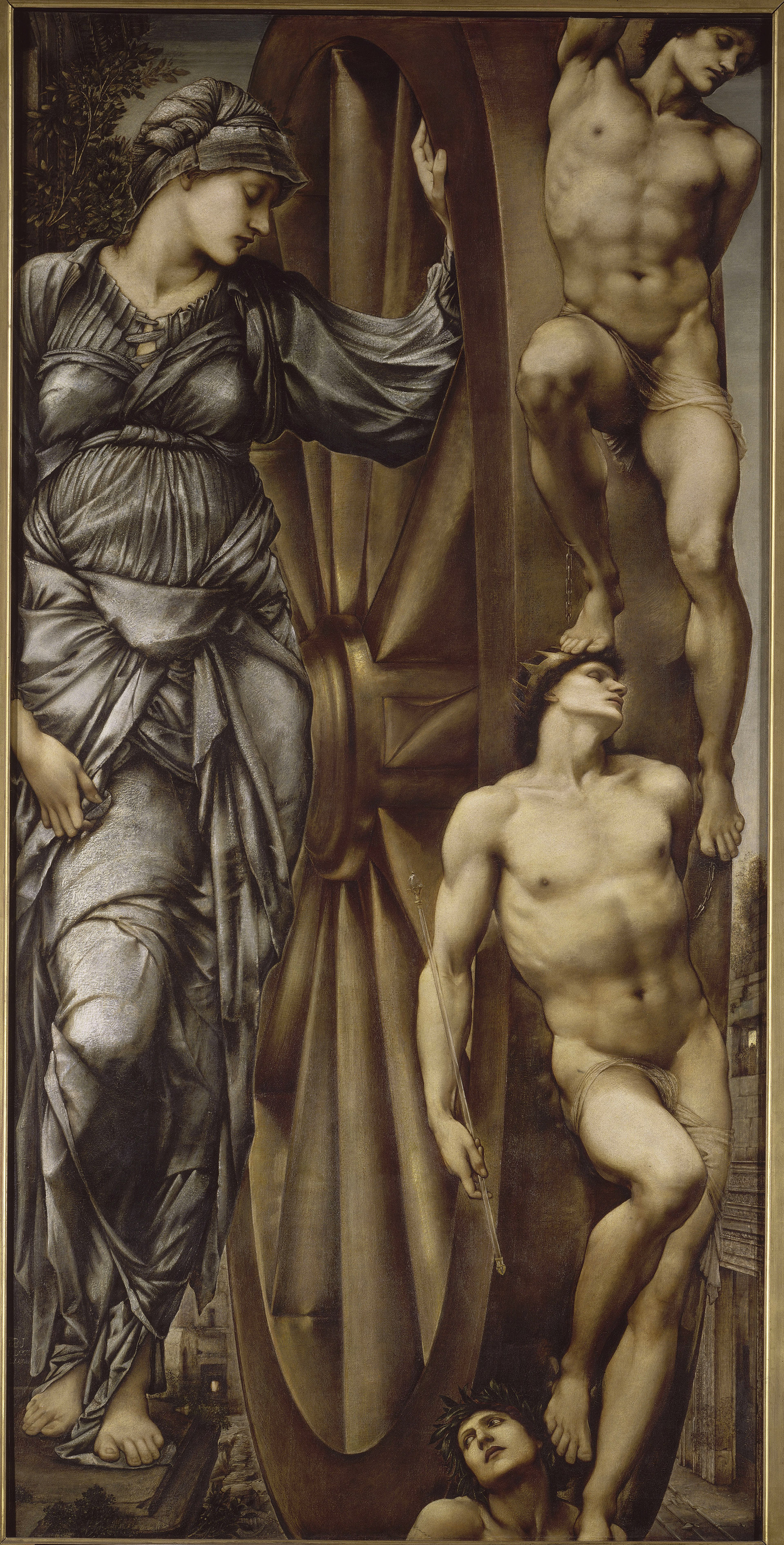

There are two known poles regarding the theological and metaphysical interplay of grace & free will, from a Roman Catholic perspective. The first, the heresy of Pelagianism, errs in assigning too great a role to free will and debasing God’s grace; the other, of course, is that of Calvinism, in which free will is negated and the operation of grace inflated to the point that we arrive at total (or double) predestination. These extremes are the Scylla and Charybdis of the theology of grace; a truly Catholic approach to this problem must sail skillfully between these two dangers, turning neither to the left nor to the right.

-by Michael Moreland

May 26, 2015

“The big story coming out of the weekend was the Irish referendum on same-sex marriage, accompanied by barely concealed glee in some quarters at the humiliation of the Catholic Church. Here’s a hypothesis to ponder about the historical reach of theological ideas and the place of Catholicism in different cultures (not so much about the substance of the same-sex marriage debate itself), even if it might not hold up in every detail to scrutiny.

As Damian Thompson writing at the Spectator notes here, the influence of Catholicism in Ireland has waned for various reasons (most especially the sex abuse scandal), and one factor he mentions in passing is “the joyless quasi-Jansenist character of the Irish Church.” Indeed, while the Church’s influence across Europe has fallen, the collapse in those parts of Europe (or places missionized by Europeans) arguably influenced by Jansenism has been ferocious: the Low Countries (we think of Jansenism as primarily a French movement, but Cornelius Jansen himself was Dutch and Bishop of Ypres), France, Quebec, and Ireland. The place of the Church in the culture of those parts of European Catholicism less tinged by Jansenism has fared a bit better: Poland, Austria, Bavaria, Italy, and, most especially, Spain and Portugal and their former colonies in Latin America and the Philippines.

I am simplifying a great deal here, of course. There was, for example, a robust Jansenist movement in parts of modern-day Italy, and, more importantly, it is hard to say how much Jansenist influence there really was in Irish Catholicism (captured by the “quasi-” in Thompson’s essay). Because of English persecution, there were no seminaries in Ireland up through the end of the eighteenth century and so Irish clergy were often trained at Jansenist French seminaries, and there might have been some Jansenist influence in the early days at Maynooth, the Irish national seminary founded in 1795. But the scope of the actual influence of Jansenist ideas on folk Irish Catholicism is much harder to determine, as Thomas O’Connor notes in his 2007 entry on “Jansenism” in The Oxford Companion to Irish History (“The frequent claim that Irish Catholicism was Jansenist-influenced springs from the tendency to confuse Jansenism with mere moral rigorism.”). Jansenism was just one (perhaps small) factor among many contributing to Seán Ó Faoláin’s “dreary Eden.”

If there is something to this, though, we shouldn’t be surprised. Jansenism—with its hyper-Augustinianism, insistence on human depravity, confused doctrine of freedom and grace, other-worldliness, and moral rigorism—was theologically pernicious (condemned in Cum occasione by Pope Innocent X in 1653 and in Unigenitus dei filius by Pope Clement VI in 1713). A Catholic culture shaped by it distorts our understanding of the human person and society, and bad theological doctrines about God, human nature, and sin can wreak havoc even if the institutional forms of the Church endure for a time. Jansenism produced a towering genius in Blaise Pascal and a minor genius in Antoine Arnauld, but it was an unfortunate development in early modern Catholicism. As we think about how to build (or re-build, as it may be) Catholic culture, we would do well to remember that joy is at the heart of the gospel, and a Catholic culture drained of such joy by Jansenism or its cousins will, when the time comes, all too easily be swept away.”

Love & the JOY!!! of the Gospel,

Matthew