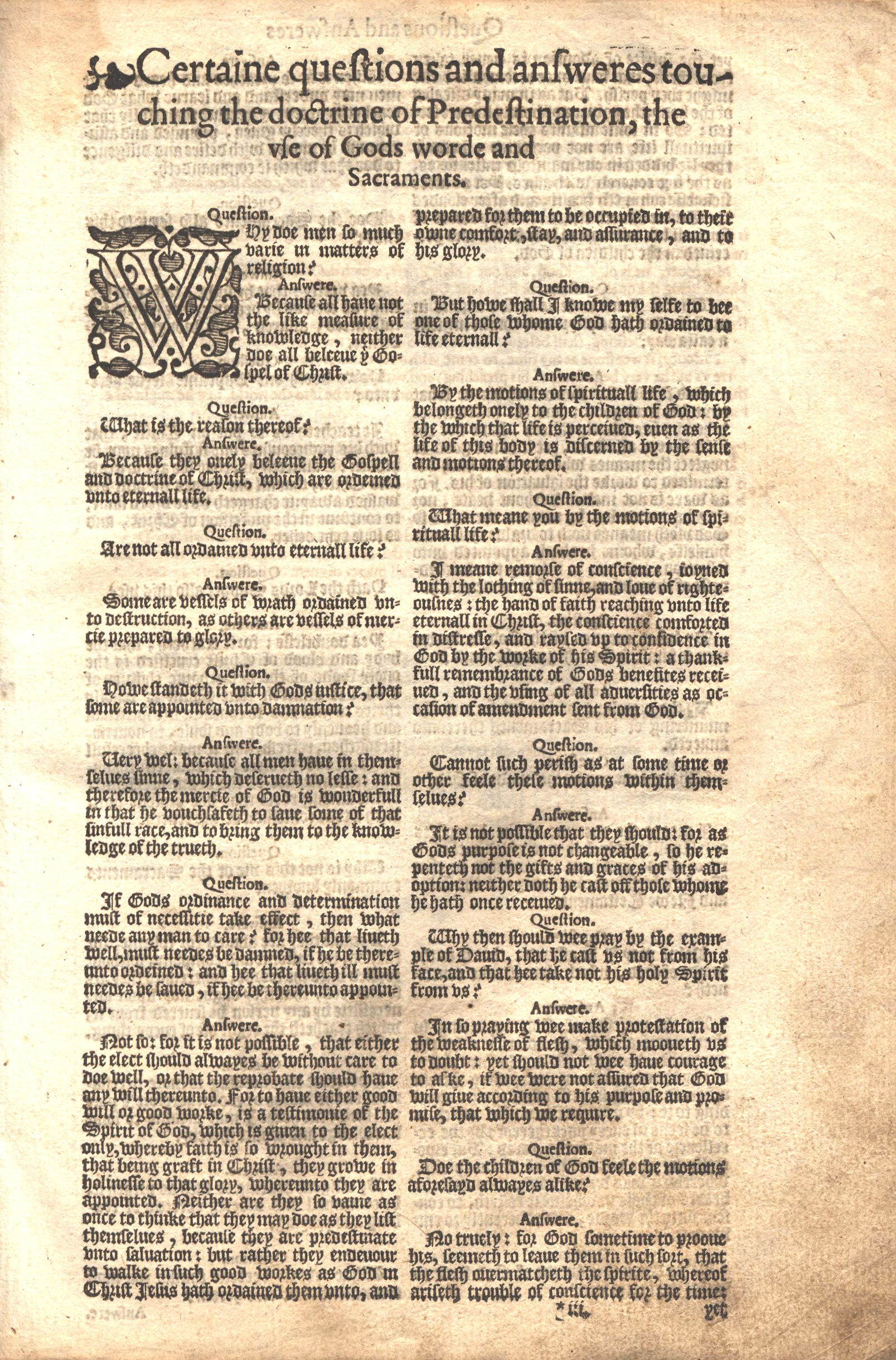

-The Doctrine of Predestination explained in a Question and Answer Format from a 1589/1594 Geneva Bible, please click on the image for greater clarity

In Christianity, the doctrine that God unilaterally predestines some persons to heaven and some to hell originated with St Augustine of Hippo during the Pelagian controversy in 412 AD. Exactly the time the Catholic Church stopped adopting the teachings of Augustine as doctrine.

Pelagius and his followers taught that people are not born with original sin and can choose to be good or evil. The controversy caused Augustine to radically reinterpret the teachings of the apostle Paul, arguing that faith is a free gift from God rather than something humans can choose. Noting that not all will hear or respond to God’s offered covenant, Augustine considered that “the more general care of God for the world becomes particularised in God’s care for the elect”. He explicitly defended God’s justice in sending newborn and stillborn babies to hell although they had no personal sin. (Limbo, merely a theological idea, not a doctrine, was a Catholic “we don’t know” answer. Realizing the necessity of baptism for salvation, but also the innocence other than original sin, but no personal sin, seems out of line logically with God’s infinite mercy and love and also His infinite Justice. Sending the personally innocent to Hell cannot be logical or just. Truth cannot contradict truth.)

John Calvin taught the latter part of “double predestination” had leaving the remainder of humanity to receive eternal damnation for all their sins, even their original sin. Calvin wrote the foundational work on this topic, Institutes of the Christian Religion (1539), while living in Strasbourg after his expulsion from Geneva and consulting regularly with the Reformed theologian Martin Bucer. Calvin’s belief in the uncompromised “sovereignty of God” spawned his doctrines of providence and predestination. For the world, without providence it would be “unlivable”. For individuals, without predestination “no one would be saved”.

Calvin did not accept the concept of free will, God’s superabundant gift of grace and salvation through Jesus Christ to all, if only for the asking; understanding due to free will and original sin, causing a darkness of the will, soul, and mind, that some would reject this superabundant free gift of eternal life.

Calvinists(Presbyterians) emphasize the active nature of God’s decree to choose those foreordained to eternal wrath, yet at the same time the passive nature of that foreordination. God gives His grace to the elect, and not to the reprobate, leaving them to themselves, and their ultimate, inevitable damnation. So, you could unwittingly be tempted to argue that there really is no difference between free will and the doctrine of reprobation, but, ahem, as they say, and truly so, the devil is in the details.

This is possible because most Calvinists(Presbyterians) hold to an Infralapsarian, the Calvinist theological discipline of the logical order of God’s decrees, view of God’s decree. In that view, God, before Creation, in His mind, first decreed that the Fall would take place, before decreeing election and reprobation. So God actively chooses whom to condemn, the reprobate, but because He knows they will have a sinful nature, the way He foreordains them is to simply let them be – this is sometimes called “preterition.”

Therefore, this foreordination to wrath is passive in nature (unlike God’s active predestination of His elect where He needs to overcome their sinful nature). So, in order to make reprobation line up with free will you have to do some logical gymnastics and hoops, which Calvinism intentionally makes you do, to come out somewhere near a fruitless effort to seem like free will, tadah; but, it’s really not.

Calvinists hold that even if their scheme is characterized as a form of determinism, it is one which insists upon the free agency and moral responsibility of the individual. How, this editor does not know.

Additionally, Calvinists(Presbyterians) hold that the will is in bondage to sin and therefore unable to actualize its true freedom. Hence, an individual whose will is enslaved to sin cannot choose to serve God. Since Calvinists(Presbyterians) further hold that salvation is by grace apart from good works (sola gratia) and since they view making a choice to trust God (free will/faith) as an action or work, they maintain that the act of choosing cannot be the difference between salvation and damnation, as in the Arminian scheme. Rather, God must first free the individual from his enslavement to sin to a greater degree than in Arminianism, and then the regenerated heart naturally chooses the good. This work by God is sometimes called irresistible, in the sense that grace enables a person to freely cooperate, being set free from the desire to do the opposite, so that cooperation is not the cause of salvation but the other way around. God saves the elect by fiat of grace to them only and personally, without personal choice or knowledge of the elect, and they cooperate with Him.

-by Karlo Broussard

“John Calvin is famous for teaching that God doesn’t just permit moral evil, but he positively directs sinners to sin. Of “wicked” and “obstinate” men, Calvin claimed that

“[God] bends them to execute His judgments, just as if they carried their orders engraven on their minds. And hence it appears that they are impelled by the sure appointment of God (Institutes of the Christian Religion, Bk. 1, Ch. 18, sec. 3; emphasis added).”

Notice that for Calvin sinners don’t sin merely because God allows them to do so (His permissive will). Rather, he “impels” or “bends” (forces) them to sin.

But is it even possible for God to cause someone to sin?

Consider that if God were to move us to sin he would be turning us away from him, away from our ultimate end or goal, “for man sins through wandering away from [God] who is his last end” (Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles 3.162). In other words, God would be moving us to not love Him, and if so, He would fail to will the divine goodness more than any other good (cf. Summa Theologiae I:19:9). And this failure would be due either to a lack of knowledge that He is the supreme good, or a failure in due attraction to Himself as the supreme good.

But God can’t possibly fail in knowledge that He’s the supreme good because He’s omniscient. Nor can He fail to be attracted to Himself as the highest good, for that would entail a desire for some good outside the order of reason, which is impossible because He’s perfectly good.

In fact, God can’t fail in any sense. Failure necessarily entails unactualized potential. But God is traditionally understood to be pure actuality, or pure existence itself, the very notion of which excludes the idea of unactualized potential. Therefore, God can’t fail lest He cease being God.

Since God moving us to sin would entail a failure on God’s part, and God can’t fail, it follows that God can’t move us to sin.

Now, someone may just reject this classical notion of God in order to keep the idea that God moves us to sin. But then there’s not much value in a deity that’s finite and subject to defect. This position undermines the very divine sovereignty that folks like Calvin seek to preserve in asserting that God moves us to sin.

The desire to preserve God’s sovereignty is laudable. But there’s another way to preserve it that doesn’t require us to give up divine perfection.

St. Thomas Aquinas teaches that God gives some people the assistance of grace that leads them to glory in heaven (an assistance that doesn’t violate human freedom), while He permits others to fall into sin, the consequence of which is deprivation of further graces ordered to salvation (SCG 3.163). And since this is all “ordered from eternity by His wisdom,” so Aquinas reasons, “it follows of necessity that the aforesaid distinction among men has been ordered by God from eternity.”

The preordination of some to be moved to their last end is called predestination. The permissive decree to not uphold someone in the good and allow that person to sin is called reprobation. On this account, both predestination and reprobation belong to God’s providence.

Nothing is lost. God’s nature as pure actuality is preserved because there’s no unrealized potential. He remains the source of all good because those who attain final glory do so because of God’s grace. God’s sovereignty is preserved because not even sin escapes his divine plan, since from all eternity He wills to permit it. Nor is God’s innocence lost because He doesn’t move us to do evil.

Now, someone might object: “This account doesn’t protect divine innocence any more than Calvin’s system, since God could have given the grace to prevent someone from sinning if He wanted to do so.”

First of all, God is not bound in justice to give us what is not our due. In the words of Rev. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, “It is natural [Ed. according God’s will, the natural law, natural revelation] that what is defectible should sometimes fail.”

As finite creatures made in God’s image who are given the gift of freedom, our final end is in Him—not in ourselves. We must therefore direct ourselves to our final end by an act of free will, in collaboration with God’s grace. But that entails the possibility to sin. So, for God to preserve us from sin by grace would be for Him to give us something over and above what’s due to us as finite rational beings. And since God is not bound in justice to himself to give us what’s not due to our nature, it follows that God is not unjust for permitting us to sin.

Now, this doesn’t mean those whom God permits to fall into sin don’t have a chance at salvation. Aquinas teaches that God “for his part, is prepared to give graces to all” (SCG 3.159). He quotes 1 Timothy 2:4 for biblical support: “[God]…desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth.” And how does He do this?

“The common and wonted course of justification is that God moves the soul interiorly and that man is converted to God, first by an imperfect conversion, that it may afterwards become perfect (ST I-II:113:10).”

God gives to all the grace that leads to an imperfect conversion, and because this grace has the potential to lead to further good acts meritorious of salvation, there’s a real chance at salvation: “the Holy Spirit in a manner known only to God offers to every man the possibility of being associated with this paschal mystery” (Gaudium et Spes 22).

With regard to the grace needed to perform more-perfect acts, like a more perfect act of conversion, God only withholds it if man resists the order that the first grace has to the more perfect act. Again, Aquinas writes,

“But those alone are deprived of grace, who place in themselves an obstacle to grace: thus he who shuts his eyes while the sun is shining is to be blamed if an accident occurs, although he is unable to see unless the sun’s light enable him to do so (SCG 3.159).”

This allows Aquinas to conclude that “God does not cause grace not to be supplied to someone; rather, those not supplied with grace offer an obstacle to grace” (De Malo q. III, a. 1, ad 8).

God does permit us to sin, but this doesn’t count against God’s goodness because He’s not bound in justice to Himself to prevent us from sinning. [Ed. His knowledge that we will sin, and that some will be damned, and even whom, does not prevent, or interrupt our free will. Knowing something does not effect or alter or change or impel a result of the consequence of free will. cf Augustine. Also, God knows every combination that can happen, so, in that way, God is omniscient. When we think of God knows the future, we fail in understanding and imagination that as only one possible thread existing preemptive and future.]

As to why God doesn’t rescue every man from sin, and allows some to fall into it, it’s a mystery. As Aquinas says, it “has no reason, except the divine will” (ST I:23:5 ad 3).

So, for anyone who wants to hold to the idea that God moves us to sin, as Calvin believed, he must hold an idea of God as a finite being who is subject to error. The view articulated by Aquinas doesn’t require this of us. It preserves God’s perfection and his divine sovereignty by allowing both predestination and reprobation to be part of God’s providence without having to say God moves us to sin.”

Love & truth,

Matthew