-Crab Nebula, please click on the image for greater detail

https://www.catholicscientists.org/idea/christian-truth-in-an-age-of-scientific-mythology

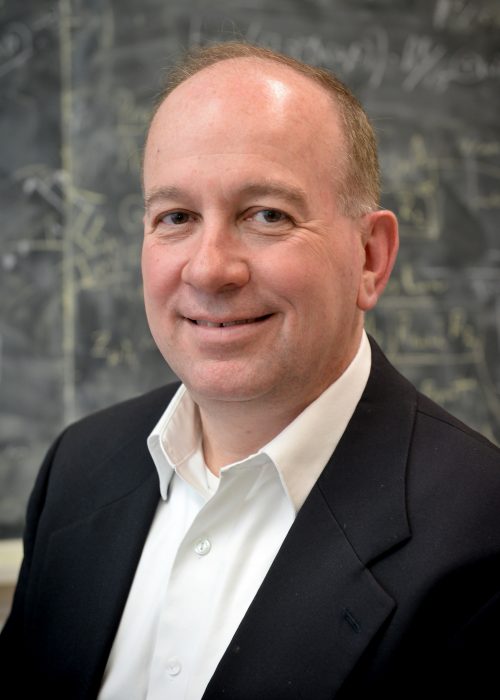

-by Dr. Christopher Clemens, PhD, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Senior Associate Dean for Research and Innovation, Jaroslav Folda Distinguished Professor of Physics and Astronomy

“It shocks many people to find out that I am both an astrophysicist and a religious believer. It shocks some of my fellow astrophysicists and even some of my fellow Catholics. And I know it shocks some of my faculty colleagues at Chapel Hill. But why should this be? Why should it be a surprise that someone whose chosen profession is the scientific study of the universe is also a person of faith? Why the perception of conflict? Is it intrinsic to the business of science that it be “at odds” with religion? Or is it rooted in cultural attitudes?

Let us start by looking at certain aspects of the wider culture and of the culture of science itself.

One of the defects of contemporary culture is the undue and unhealthy reverence we show toward scientists. The public imagines scientists to be too smart to disagree with, too objective to be swayed by emotion or bias, and experts on every subject they choose to talk about. None of these things is true, of course, and the unquestioning acceptance of these notions does great harm. When the physicist Stephen Hawking said that his theories show that the universe has no cause, but simply “is”, or when the biologist Richard Dawkins rails against religion as a “virus” that should be eradicated, their words are given much weight. They are the great minds of our time, our culture supposes, and therefore we are not smart enough even to disagree.

In truth, scientists are anything but authorities on subjects philosophical, and have strayed very far from their own scientific method when they make these kinds of pronouncements. The question of why their words carry so much weight is an interesting one, and deserves to be studied, but here I want to explore what lies behind some of their anti-religious pronouncements. What I hope becomes apparent is that while scientists might be very good at their jobs, their thinking on the subject of religion is not always objective and clearheaded.

To begin, I need to introduce a concept that sounds like an oxymoron: “Scientific Mythology.” The great majority of agnostic or atheist scientists criticize Christians for their “superstitions,” but their own world views are often constructed around a kind of mythology, with scientists themselves as the mythic heroes. The enemy (or, more romantically, the “dragon”) in their myths is anything that stands in the way of free inquiry and the advancement of knowledge. In their terms, the enemy is “dogma,” and they will have none of it. These same scientists do not see that holding the advancement of knowledge or free inquiry as the supreme good is itself a kind of dogma; and this should help us realize that scientists are not always flawless in their logic.

In any event, a typical story in Scientific Mythology has as its hero a person with a new idea, and the story works best if the idea can be described as “heretical” — an adjective many scientists use to confer honor. In the course of the story, the hero encounters a “dogmatic” villain, preferably an immensely powerful one, and is often vanquished in body and spirit, but never in mind, and at the climax of the story he may mutter under his breath, “e pur si muove” (“it moves nonetheless”) or some other phrase to tell us that he has not given up his idea. The moral is always the same: today we know the “heretical” idea is correct, and we can scoff at the dogmatic villain who was powerful but wrong and honor the freethinking hero who was weak but right.

Many scientists are wedded to this kind of mythology to such an extent that it warps their view of history, adversely affects their scientific work, and even compromises their honesty. These are serious charges, the most serious ones you can level against a scientist, but I base them on close experience. Let me tell a story that illustrates what I am saying.

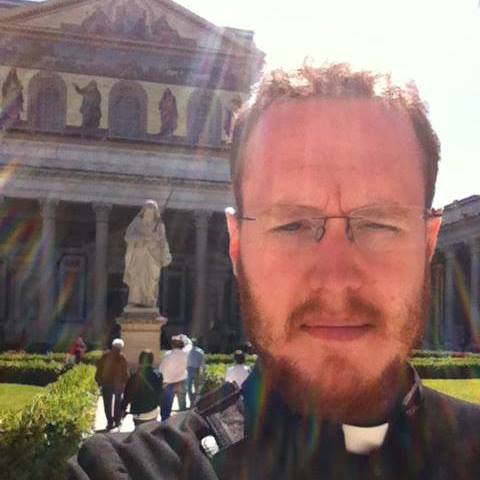

When I was a graduate student at the University of Texas, many of the professors there taught a scientific myth about the Crab Nebula and the Supernova of 1054. The Crab Nebula is a wispy cloud of gas and dust visible in the northern skies, which astronomers believe is the remnant of an exploding star called a supernova. Based on the distance to the nebula, and the rate that material in the nebula is expanding outward, we can calculate the year (1054 A.D.) that the supernova would have appeared in the sky and how bright it would have been. As it happens, in that year, Chinese and Japanese astronomers recorded the presence of a new star, bright enough to be seen even in daytime, which is what we would expect. However, there is no record that the event was seen in Europe.

From this absence of recorded evidence grew the myth taught by many of the UT astronomy faculty (which I have now traced back at least as far as The Feynman Lectures on Physics). The supernova of 1054, they taught, was not reported in Europe because the Europeans were in the grip of the Dark Ages, and the powerful and dogmatic Catholic Church enforced Aristotle’s view that the stars were unchanging. This Church was so effective at suppressing the observations that none survived in all of Europe.

This story has all the basic elements of Scientific Mythology magnified many times. The supposedly heretical idea, that a new star could appear, was verifiable by anyone who had eyes to see. The dogmatic villain was so powerful that it could convince the poor ignorant masses of a whole continent that they could not believe what their own eyes told them. A dark age indeed! Thank Newton we live in better times!

There’s just one problem with the story, it is patently ridiculous. Anyone who can read the Gospels will have a first inkling that something must be wrong with it: “Where is the newborn king of the Jews? We observed his star at its rising and have come to pay him homage.” (Matthew 2:2) It is difficult to reconcile a dogmatic position that the heavens are unchangeable with a newly appeared Star of Bethlehem of Matthew’s Gospel. Or are we supposed to believe that Aristotle held a higher position in the medieval mind than even the Gospels? Well, it really doesn’t matter, because anyone who knows Western history, that increasingly esoteric and unpopular subject, will see a bigger problem. The ideas of Aristotle were nearly completely unknown in Latin Europe in 1054. Not until the 13th century did St. Thomas Aquinas and other Scholastic thinkers attempt to adapt Aristotelian thought to the foundations of Christian theology, and this was greeted with great suspicion at first.

To continue the story, near the end of my graduate studies at UT, I spent a lot of time working in the library, and I came across a book — I believe it was called The Historical Supernovae — and read an account of the supernova of 1006. This one was brighter than the supernova of 1054 and a little further south, and it was also reported in China and Japan, and … in the records of a European monastery. At this point, I had had enough. I copied the page from the book and brought it to one of our weekly group lunches. At the end of the meeting, I showed it to a professor whom I had heard teach the “mythological” version. He was a man whose scientific integrity I respected. I told him that he and many of the professors were teaching an error in the introductory astronomy classes. I explained everything that I have explained above, ending with an emphatic flourish: “and so, unless you have a convincing theory that some radical dogmatic change occurred in the 48 years between 1006 and 1054, you should probably change what you teach about the supernova of 1054.”

What do you suppose he said? His one-sentence reply was “I’m still going to teach it the way I always have.”

Apparently, his myth meant more to him than the truth. And he’s not the only one. I have found lots of interesting references to the myth of the Supernova of 1054. The most interesting is from a 1998 issue of Natural History magazine and was written by the director of the Hayden Planetarium (none other than Neil deGrasse Tyson), in an article, ironically enough, about the importance of checking the evidence before you believe something:

“In scientific investigations of the natural world, the only thing worse than a blind believer is a seeing denier. In A.D. 1054, a star in the constellation Taurus abruptly increased in brightness by a factor of one million. Chinese astronomers wrote about it. Middle Eastern astronomers wrote about it. Native Americans in what is now the southwestern United States made rock engravings of it. The star became bright enough to be seen in the daytime sky for weeks, and it continued to be visible in the night sky for months. Yet we have no record of anybody in all of Europe documenting the event.”

Tyson’s explanation:

“[But] Aristotle had said the stars don’t change. The Church, with its unmatched authority, promulgated the idea. People accepted it, believed it: a collective delusion that was stronger than their own powers of observation.”

Later in the same article, referring to some of the commonly held misconceptions about astronomy, Tyson lamented,

“One would think that in our modern and enlightened culture, people would be immune to believing falsehoods that are easily testable. But we are not.”

What can one say, except “how true”? You are allowed one guess as to where Neil de Grasse Tyson conducted his graduate studies….The University of Texas. (I know this because I was studying there at the same time.) Thus is the Scientific Mythology passed on to the next generation, except, with Tyson, the size of the forum is quite a lot larger. In a final irony, I found a 1999 article that claims to have found evidence that the 1054 supernova actually was reported in European records. But even that article couldn’t let go of the mythological version so easily. It ends by noting that Europeans never reported seeing the supernova in the morning, as the Asians did, and then speculates that the Roman church may have suppressed only the morning observations. Right … or maybe they just slept later in Europe.

There are many other examples of Scientific Mythology one could cite. Many of them have to do with the case of Galileo, which involved real abuse of authority and real injustice, though not as clear-cut as in the mythological versions.

To see how distorted the story of Galileo has become, consider the following fact that many historians and scientists forget to mention: the evidence Galileo presented for the motion of the Earth in his “Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems” had to do with ocean tides and is completely wrong. Not his conclusion, mind you — the Earth does move — but the evidence he presented for it. So his critics in the Church were not wrong to insist on better proof before taking his advice about re-interpreting Scripture in light of heliocentric theory.

Scientific Mythology unfairly distorts history, but is often innocent and rather juvenile. Sometimes, however, it is coupled with something more pernicious, namely the idea that science and Christianity are in fundamental opposition. This usually takes the form of what one may call “Scientific Triumphalism”, in which science completely displaces theology, philosophy and everything else as the sole tool for understanding our existence.

Scientific Triumphalism is harmful both to science and to Christianity, and so full of subtle errors that I’m sure I haven’t worked them out fully. So let me proceed again with examples. I borrow the first example from the late Stephen Hawking, who was Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge University, the very chair that Newton held. In a 2002 article from his 60th birthday symposium, Hawking described the situation in theoretical cosmology at the beginning of his career. (See http://plus.maths.org/issue18/features/hawking/) The big question in cosmology at that time (the early 1960s) was whether the universe had a temporal beginning, i.e. a first moment of time. Many scientists were instinctively opposed to this idea, because they felt that a first moment could be seen as a “point of creation.” It might even be a place where science broke down and one might have to appeal to the hand of God to set the “initial conditions” of the universe.

This widespread prejudice against the idea that the universe had a beginning grew out of the materialist philosophies of the 19th century, and by 1917 it held such sway that Einstein himself was afflicted with it. When Einstein improved upon Newton’s theory of gravity and used his new theory to construct the gravitational equations governing the universe, he found that there was no “static solution,” that is, the equations suggested that a universe dominated by gravity would either expand or contract. This idea was so philosophically “repugnant” (his word) that he added a constant, or “fudge factor” if you like, to the equations to balance them out. In effect he forced the equations to describe an eternal universe. He later called this his “biggest blunder”. The consequence of his blunder was that he failed to predict the cosmic expansion that Edwin Hubble would measure in 1929.

As it happened, there was a less dogmatic hero in this story, who took seriously the possibility, suggested by the equations, that the universe could be expanding. Do know who he was? His story falls so far outside the standard Scientific Mythology that you seldom hear it or even his name. He was the Belgian theoretical physicist and Catholic priest Georges Lemaître. Lemaître used Einstein’s Equations to construct the theory that later became known as the Big Bang theory and to predict the expansion of the universe two years before Hubble measured it. Here’s what Fr. Lemaître had to say about science and religion in his life: “There were two ways of arriving at the truth. I decided to follow them both.” He also said,

“Nothing in my working life, nothing I ever learned in my studies of either science or religion has ever caused me to change that opinion. I have no conflict to reconcile. Science has not shaken my faith in religion and religion has never caused me to question the conclusions I reached by scientific methods.” [Editor: me neither.]

To continue Lemaître’s story, the initial response of some to his theory of an expanding universe with a finite age was dismissal and even derision. Fred Hoyle, a Cambridge astronomer of firm atheist convictions, applied the name “Big Bang” to the theory as mockery. Hoyle hated the idea of a universe with a beginning, even after Hubble’s discovery that the universe is expanding. He did not believe the question was settled, but proposed that as the universe expanded new matter was constantly appearing to fill the void, so that the Universe could still be eternal. Hoyle was happier with the spontaneous and unobserved generation of new matter (which violated the principle of conservation of energy) than he was with a cosmic beginning.

Fortunately, one of the great features of scientific inquiry is that it relies upon observations of the universe itself to correct any biases that theorists might have. And that is what happened in the case of the “Big Bang” theory. In 1965, when radiation from the “primordial fireball” of Lemaître’s theory was observed by Bell Labs engineers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, even the diehard skeptics were convinced, and now the Big Bang is the standard model astronomers and physicists use to think about the universe. And almost all of them agree it had some kind of beginning very different from the conditions we see now. Happily, Fr. Lemaître is now beginning to receive greater honor from scientists for his contributions. In 2018, the members of the International Astronomical Union voted overwhelmingly to recommend that the famous “Hubble Law” describing the expansion of the universe should henceforth be called the Hubble-Lemaître Law. And this is another wonderful thing about science, which should give us hope: in the end truth does tend to win out over myth and prejudice.

My second example of Scientific Triumphalism are the radically reductionist views of Evolution of the kind promoted by Richard Dawkins and others.

Evolution by natural selection is an elegant, though incomplete, theory and a theory I enjoy thinking about very much. As a scientific theory, it is no more problematic for religion than the study of fetal development. If I tell my children in one moment that they were made by God and in the next I explain how they grew in their mother’s womb from a single cell through a set of magnificently orchestrated chemical reactions, I do not commit any theological or scientific error. As I once put it to a Christian audience, “Ladies and gentlemen, no laws of physics were broken in the creation of this human being you see here before you.” Reproduction strikes me as an economical way to create. And it illustrates a general principle of Catholic theology, which was stated as follows by the great Jesuit theologian Francisco Suarez (1548-1617): “God does not interfere directly with the natural order, where secondary causes suffice to produce the intended effect.”

Of course, fetal development is not only economical, it is also marvelous, wonderful, and, if you have ever tried to build anything remotely complicated, awe-inspiring.

Before applying the same logic to evolution, it is important to be clear about the meaning of the word. To “evolve,” in the literal sense of the word, is to “unfold.” If the unfolding of the first man and woman was through natural selection acting on the well-regulated natural interactions of matter, then what is there in that to threaten our faith? In saying this, am I going way out on a theological limb? Well, listen to what the great St. Augustine wrote more than sixteen centuries ago in his work De Genesi ad Litteram (“On the Literal Interpretation of Genesis”):

“But from the beginning of the ages, when day was made, the world is said to have been formed, and in its elements at the same time there were laid away the creatures that would later spring forth with the passage of time, plants and animals, each according to its kind. . . . In all these things, beings already created received at their own proper time their manner of being and acting, which developed into visible forms and natures from the hidden and invisible reasons which are latent in creation as causes. . .”

That is about as good an anticipation of evolution as one could imagine. And St. Augustine proposed it for theological reasons. So why is evolution considered so controversial and problematic, and why do even some Catholics feel a pit in their stomachs when some eminent biologists teach and defend the theory? Part of the reason is that some of these biologists are like the astronomers I described above. Some of them are interested not only in teaching us about evolution but also in telling us what it means … their materialist and triumphalist version of what it means. Which usually translates into “God is dead at last.”

For example, Jacques Monod, molecular biologist and 1965 Nobel laureate in medicine, argued in his book Chance and Necessity that because we arise from a process involving chance events we cannot be the result of any foresight, nor can we be the fulfillment of any purpose, divine or otherwise. “Destiny,” he said, “is written concurrently with the event, not prior to it.” Richard Dawkins, the most effective popularizer of evolutionary theory, is more blunt: “All appearances to the contrary, the only watchmaker in nature is the blind forces of physics… Natural selection has no purpose in mind, it has no mind and no mind’s eye. It has no vision, no foresight, no sight at all.” Along with their presentation of evolutionary theory, both of these atheists present, as a logical conclusion of the theory, that we cannot be the result of any design.

My first response to this is that it is a logical fallacy. The presence of randomness in a process might just as much be evidence for design as against. In recent years, a whole new field of computational physics has emerged that relies upon the same principles we find in evolutionary theory. In this new field, programmers construct “genetic algorithms”, which breed and randomly mutate solutions to complex equations; and then they use these algorithms to explore the properties of physical systems. It turns out that this is the most efficient way to explore solutions to some complicated problems, and yet it relies on randomness and selection based on fitness. If we came upon a computer running one of these algorithms, we would not be able to discern its purpose simply by observing it in operation, but we would err if we supposed from its use of random mutation that it had no purpose or design.

For the more poetic, a different analogy: just as dust sprinkled randomly on a surface can reveal the prints left by a hand, so could the random exploration of physical forms reveal latent creatures laid down by God’s design in the very potentialities of matter. I don’t pretend to be proving that this is true, only showing that the randomness and selection by fitness intrinsic to evolutionary theory is not prima facie evidence against God, no matter what some well-known biologists may say.

I would also point out a curious paradox. In the interval of history between Isaac Newton and Werner Heisenberg, materialists told us God was dead because the laws of physics were deterministic. Once the initial conditions were fixed, the universe played out without the chance for free will. At best we could have Deism, where God winds things up and then sits back to watch. But it wouldn’t be a very interesting show since the end was fixed at the beginning. Now we know better, we know that all interactions in nature are pervaded with intrinsic randomness, including the interactions of beings like us. And what do materialists tell us this means? … That God is dead!

One of the problems with Scientific Triumphalism, the notion that science has displaced all other ways of arriving at truth, is that there are many questions it cannot provide answers to, including most of the important questions of life and how we should live our lives.

Modern science as we know and practice it emerged in the early modern period within a Western Christian culture. In the service of human flourishing it has done great good. But in an increasingly secularized West, science as a methodology for solving problems is in constant danger of pulling loose from its religious and spiritual moorings. Whenever this happens, the result is disaster. In ethics and in morality science cannot provide for itself. There are two things in particular it has to borrow from elsewhere, and these are “compassion” and “hope”. Concerning compassion, one way to put the problem is this: “compassion for the weak is not a principle of science.”

The more you think about that the more frightening it becomes. To be fair, all of the atheist scientists I have known who claimed to live by science alone actually had quite a lot of compassion for the weak. Whether this arose from the “law written in their hearts” by God (Romans 2:14-5) or from breathing what is left of the increasingly rarified religious component of the atmosphere of our culture I cannot say. But this compassion was certainly not an outgrowth of their scientific materialism. I have always been simultaneously puzzled by and grateful for the compassion of atheists, but I never inquire too deeply about it, out of fear I might trigger a recognition of what I have just told you: “compassion for the weak is not a principle of science.”

In fact, compassion for the weak is the virtue science most easily forgets. The flirtation with eugenics in the last century was an attempt to improve the human race by eliminating the so-called weak. In the United States it resulted in forced sterilizations and in Europe millions died. In the future, when we have constructed clear enough genetic maps to choose precisely between the weak and the strong, how many millions will die? The machinery is already in place, and our culture has already declared its willingness to cooperate in such an “improvement project” by assenting to the abortion of many millions of children.

In addition to “compassion for the weak,” science lacks the route to another important virtue, and that is hope. From observation we know not only that each of us will die, but that in the distant future our planet will undergo the same fate. Even if there is no catastrophic asteroid collision that wipes out all life sooner, in 5 billion years or so the sun will grow into a red giant star, boil away the earth’s oceans and atmosphere and leave a lifeless rock. Everything we have ever created or will create will be lost forever. Even if we can move elsewhere, the increasing expansion of the universe will eventually mean energy is too dilute to sustain life. Science gives us no reason to hope in the face of existential fears.

And the loss of hope has become a serious problem in the secular world. What is the leading cause of violent death worldwide? Is it war, or homicide? It’s neither. According to the World Health Organization, the leading cause of violent deaths is suicide, which is roughly twice as common as homicide and seven times more common than death from violent conflict. In many ways we live in our own Dark Ages, an era of despair. Never have so many, with so much, been so unhappy. Science can show us how to live longer, but it cannot show us how we ought to live or even that we ought to live.

Science itself is a great good and a great gift. It is not and never has been an enemy of religion. What is harmful to religion, and not only to religion but to science itself, is what I have called Scientific Mythology and Scientific Triumphalism. These are cultural phenomena that do not stem from the discoveries of science but from the vanity of some scientists who are unable to put science in proper perspective.”

Love & truth,

Matthew