-Matteo di Giovanni, a tempera on panel painting by Matteo di Giovanni, produced between 1450 and 1500 possibly in 1468, 1478, or 1488) probably in Siena. It was commissioned by Alfonso II of Naples, then living in Siena as part of the campaign against the Medici. It was probably produced to commemorate the inhabitants of Otranto killed by the Ottomans in 1480 whose relics were moved into the church of Santa Caterina at Formiello at Alfonso’s request – the same church also originally housed the painting. It is now in the National Museum of Capodimonte. Please click on the image for greater detail.

“When Herod realized that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under, in accordance with the time he had learned from the Magi.

Then what was said through the prophet Jeremiah was fulfilled:

“A voice is heard in Ramah,

weeping and great mourning,

Rachel weeping for her children

and refusing to be comforted,

because they are no more.””

-Mt 2:16-18

Jewish historian Josephus mentions in his Antiquities of the Jews (c. AD 94), which records many of Herod’s misdeeds, including the murder of three of his own sons

The first non-Christian reference to the massacre is recorded four centuries later by Macrobius (c. 395–423), who writes in his Saturnalia:

“When he [Emperor Augustus] heard that among the boys in Syria under two years old whom Herod, king of the Jews, had ordered killed, his own son was also killed, he said: it is better to be Herod’s pig, than his son.”

Coventry Carol

Lully, lullay, thou little tiny child,

Bye bye, lully, lullay.

Thou little tiny child,

Bye bye, lully, lullay.

O sisters too, how may we do

For to preserve this day

This poor youngling for whom we sing,

“Bye bye, lully, lullay”?

Herod the king, in his raging,

Chargèd he hath this day

His men of might in his own sight

All young children to slay.

That woe is me, poor child, for thee

And ever mourn and may

For thy parting neither say nor sing,

“Bye bye, lully, lullay.”

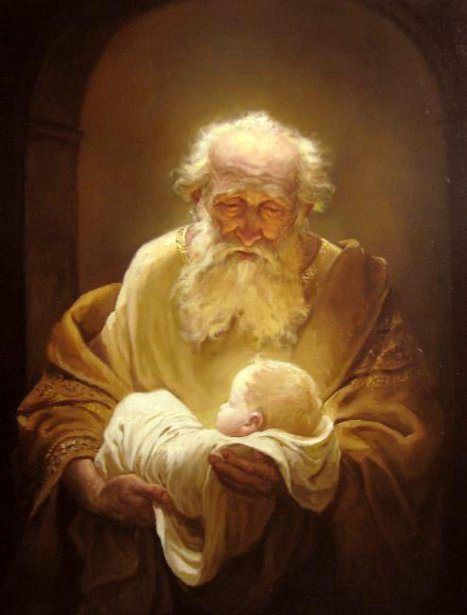

The commemoration of the massacre of the Holy Innocents, traditionally regarded as the first Christian martyrs, if unknowingly so, first appears as a feast of the Western church in the Leonine Sacramentary, dating from about 485 AD. The earliest commemorations were connected with the Feast of the Epiphany, 6 January: Prudentius mentions the Innocents in his hymn on the Epiphany. Pope St Leo the Great in his homilies on the Epiphany speaks of the Innocents. Fulgentius of Ruspe (6th century AD) gives a homily De Epiphania, deque Innocentum nece et muneribus magorum (“On Epiphany, and on the murder of the Innocents and the gifts of the Magi”).

-by Trent Horn

“Matthew 2:12 tells us that the Magi were warned in a dream not to return to Herod the Great after visiting Jesus and his family, and so they departed for their country by another way. Herod, upon realizing their failure to report to him, subsequently ordered all the male children in Bethlehem under the age of two to be executed (Matt. 2:16). Atheist C.J. Werleman wrote of this story:

[T]here is no record of King Herod or any Roman ruler ever giving such an infanticidal statute. In fact, the ancient historian Josephus, who extensively recorded Herod’s crimes, does not mention this baby murdering, which would undoubtedly have been Herod’s greatest crime by far.

Now, it is true that Matthew did not intend to write a literal history of Jesus’ birth. The evangelist uses various narrative devices in order to underscore the reality of Jesus being the “new Moses.” On that view, one of those devices could be the creation of a story that parallels the slaughter of the Hebrew infants from which Moses was spared (Exod. 1:22).

But this approach to Scripture often evinces a “hermeneutic of suspicion” and begins with an assumption that denies not just the miraculous but also the providential. From this perspective, real historical events can’t “rhyme” with one another in order to demonstrate God’s sovereignty over time and space. Any such “marvelous coincidences” have to be explained as the inventions of a rather mundane author who is just riffing on older source material.

The evidence does not, however, point to the Gospels being such purely allegorical accounts. Matthew’s narrative diverges significantly from Moses’ birth story. For example, Jesus is raised by his mother instead of in Herod’s court and Moses flees as an adult from Egypt whereas Jesus flees as a child to Egypt. In his book Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives, Pope Benedict XVI wrote,

What Matthew and Luke set out to do each in his own way, was not to tell “stories” but to write history, real history that had actually happened, admittedly interpreted and understood in the context of the word of God. Hence the aim was not to produce an exhaustive account, but a record of what seemed important for the nascent faith community in the light of the word. The infancy narratives are interpreted history, condensed and written down in accordance with the interpretation.

But what about the argument from silence that atheists like Werleman make? If this massacre really did happen, then why didn’t any other author—biblical or non-biblical—record it?

First, Mark and John do not discuss any of the events surrounding Jesus’ birth, so we wouldn’t expect them to talk about the slaughter of the innocents. Second, Luke and Matthew’s accounts are complementary, not redundant, and so it isn’t surprising that there are details unique to each account be it Matthew’s description of Herod’s slaughter of the innocents or Luke’s description of Caesar Augustus’ enrollment of the population in what later authors describe as a “census” (Luke 2:1).

Such an act of cruelty perfectly corresponds with Herod’s paranoid and merciless character, which bolsters the argument for its historicity. Josephus records that Herod was quick to execute anyone he perceived to threaten his rule, including his wife and children (Antiquities 15.7.5–6 and 16.11.7). Two Jewish scholars have made the case that Herod suffered from “Paranoid Personality Disorder,” and Caesar Augustus even said that it was safer to be Herod’s pig than his son.

In addition, first-century Bethlehem was a small village that would have included, at most, a dozen males under the age of two. Josephus, if he even knew about the massacre, probably did not think an isolated event like the killings at Bethlehem needed to be recorded, especially since infanticide in the Roman Empire was not a moral abomination as it is in our modern Western world.

Herod’s massacre would also not have been the first historical event Josephus failed to record.

We know from Suetonius and from the book of Acts that the Emperor Claudius expelled the Jews from Rome in A.D. 49, but neither Josephus nor the second century Roman historian Tacitus record this event (Acts 18). Josephus also failed to record Pontius Pilate’s decision to install blasphemous golden shields in Jerusalem, which drove the Jews to petition the emperor for their removal. The Alexandrian philosopher Philo was the only person to record this event.

Sometimes historians choose not to record an event, and their reasons cannot always be determined. In the nineteenth century Pope Leo XIII noted the double standard in critics for whom “a profane book or ancient document is accepted without hesitation, whilst the Scripture, if they only find in it a suspicion of error, is set down with the slightest possible discussion as quite untrustworthy” (Providentissimus Deus, 20).

We should call out this double standard when critics demand that every event recorded in Scripture, including the massacre of the Holy Innocents, be corroborated in other non-biblical accounts before they can be considered to be historical.”

-Le Massacre des Innocents by Sebastien Bourdon, early 1640s, oil on canvas, height: 126 cm (49.6 in); width: 177 cm (69.6 in), Hermitage Museum, Paris, France, please click on the image for greater detail

Love & truth,

Matthew