The Flying Nun you’ve probably heard of. (Sally Field/Sister Bertrille, ora pro nobis!) And, school has begun. And, school is hard these days. There is more to learn than ever and more than ever riding on success. Even adults have to go back to school these days to remain competitive.

That is not intended to pressure students any more than they already pressure themselves, the successful ones and even the ones that try as hard as they can but are not as successful. Students lack adult perspective, by definition. Unless successful at or preferably beyond their and their guardians’ expectations, they do not understand yet/have the maturity to embrace failure as a means of personal growth and realize its value, and even be thankful for it/rejoice in it for the new perspectives it brings and the death of the old way of seeing and thinking. It brings in life sweet revelations and humility. I, obviously, require MUCH more! 🙂 Deo gratias!

The young need our support and encouragement always. It’s tough out there for the young. They are not permitted the joy and luxury, to which all young persons should be, of being young very long these days. What a shame for them and for us. The young refresh us. Take us back to happier days of simpler moments in our lives/redeem us; most of us. (cf Mt 18:3)

Although, not regular supplicants, the most unspiritual student, even non-Catholics, have been known to offer the occasional prayer during examination or other stressful scholarly moment to St Thomas Aquinas, or in this case, St Joseph of Cupertino. Couldn’t hurt, right? 🙂

Joseph, as a child, was noticed to be remarkably unclever, dull, dimwitted. We might consider him today mentally disabled. But, God writes straight with crooked lines (~ancient Portugese proverb).

Born Giuseppe Maria Desa in Cupertino, Apulia, June 17, 1603, Joseph’s father, Felice Desa, was a poor carpenter in the fortified town of Cupertino, located in the heel of the boot of Italy, on the Apulian peninsula within the then Kingdom of Naples. He died before the boy was born.

Known locally as a charitable man, Felice often guaranteed the debts of his poorer neighbors, often driving himself into debt as a result. Felice died prior to Joseph’s birth, leaving his wife Francesca Panara destitute and pregnant with the future saint.

Creditors drove his mother, Francesca, from her home, sold to pay Felice’s debts. Because of this, Joseph was born in the stable behind their home. (Sound familiar? Now WHERE have I heard that before? Think. Think. Think. Nope. Nothing.)

Starting at age eight, he became prone to ecstatic visions that left him gaping and staring into space. His childhood detractors gave him the pejorative nickname, “the Gaper.” He had a hot temper, which his strict mother worked to overcome. Francesca became hardened by her circumstances, and everything became Joseph’s fault.

Joseph knew he was not as quick as the others, or athletic, or comely. Other children were praised. Joseph was not. Other children were given presents or nice clothes. Joseph was not. Absent-minded, awkward, nervous, sudden noises such as the ringing of a church bell would cause Joseph to drop all his books on the floor. He even had trouble making friends. He couldn’t carry on a conversation or tell a story. His very sentences would stop in the middle because he could not find the right words, no matter how he tried. Joseph was something of a trial, to even those who tried to love him. Nobody wanted Joseph. He learned this early on. He began to think of himself as a dumb mule, a jackass. When called to account, his only response would be, “I forgot.”

Apprenticed to a shoemaker, Joseph made a very poor cobbler, but he kept trying. At age 17 Joseph applied for admittance to the Friars Minor Conventuals, but was refused due to his lack of education. He applied to the Capuchins, was accepted as a lay-brother in 1620, but his ecstasies made him unsuitable for work. Often he was taken in ecstasy and, oblivious of what he was doing, he would drop the food or break the dishes and trays. As a penance, bits of broken plates were fastened to his habit as a humiliation and reminder not to do the same again. Eventually, he was dismissed. His habit taken from him, he was told to go. It was the hardest day of his life. When they took his habit, it was like their taking his skin from him, he said. Now what was he going to do? Could he do? Joseph was despondent.

That was not the end of his troubles. When he had recovered from his stupor on the road outside the friary, he found he had lost some of his lay clothes. He was without a hat; he had no boots or stockings, his coat was moth-eaten and worn. Such a sorry sight did he appear, that as he passed a stable down the lane some dogs rushed out on him, and tore what remained of his rags to still worse tatters.

Having escaped from the dogs, poor Joseph trudged along, wondering what next would happen. He passed some shepherds tending sheep. They took him for a dangerous character. When questioned he could give no account of himself and they were about to give him a beating; fortunately one of them had a little pity, and persuaded them to let him go free. But it was only to pass from one trouble into another. Scarcely had he gone a little further down the road when a nobleman on horseback met him. The latter could see in Joseph nothing but a suspicious tramp who had no business in those parts, and thought to hand him over to the police; only when, after examining him, he had come to the conclusion that Joseph was too stupid to be harmful did he let him go.

At last, torn and battered and hungry, Joseph came to a village where one of his uncles lived. He was a prosperous tradesman there, with a thriving little shop of his own; and Joseph hoped he would find with him some kind of comfort, perhaps another start in life. But he was sadly disappointed.

Nephews of Joseph’s type, even at their best, are not always welcome to prosperous uncles, much less when they turn up unexpectedly, with scarcely a rag on their backs. Joseph’s uncle was no better and no worse than others. He looked at the poor lad who stood before him, soiling his clean shop floor with his dirty, bare feet, disgracing himself and his house with his rags, and he was just a little ashamed to own him as a nephew.

Evidently, he said to himself, the boy had inherited his father’s improvident ways, and would come to nothing good. He was already well on the road to ruin; to help him would only make him worse. Besides, Joseph’s father already owed him money; how, then, could he be expected to do anything for the son?

So instead of offering him assistance, Joseph’s uncle turned upon him; blamed him for his sorry plight, which, he said, he must have brought upon himself; railed at him because of his father’s debts, which such a son could only increase; finally pushed him into the street, without a coin to help him on his way. There was nothing to be done; he must move on; nobody wanted Joseph.

At last he reached his native town, and made for his mother’s cottage. During Joseph’s absence, things had gone no better than before. He came to the door in fear and trembling, remembering well how his mother had long since tired of his presence. Still he would venture; it was the only place left where he might hope for a shelter and he must try. He opened the door and looked in; inside he found his mother, busy about her little hovel. Weary and footsore, hungry and miserable, no longer able to stand, he fell on the floor at his mother’s feet; he could not speak a word, though his glistening eyes as he looked up at her were eloquent.

But they failed to soften his mother. She had gone through hard times enough and was unprepared for more. What? Had he come back to burden them, now when things were worse than ever? And further disgraced, besides, for had he not been expelled from a monastery? How the neighbors would talk, and scorn the mother for having such a son; an unfrocked friar, a ne’er-do- well, a common tramp, and that at an age when other youths were earning an honest livelihood! She could restrain herself no longer. As he lay at her feet she rounded on him.

“You have been expelled from a house of religious,” she cried. “You have brought shame upon us all. You are good for nothing. We have nothing for you here. Go away; go to prison, go to sea, go anywhere; if you stay here there is nothing for you but to starve.”

But she was not content with only words. She had a brother who was a Franciscan, holding some sort of office. In high dudgeon, she went off to him, and gave him a piece of her mind about the way his Order had dismissed her son, and put him again on her hands. She appealed to him to have him taken back, in any capacity they liked; so long as she was rid of him, they could do with him what they chose. But as for readmission, the good Franciscans were immovable. Joseph had been examined before, and had been declared unsuitable; he had been tried, and had been found wanting; the most they could do was to give him the habit of the Third Order, and employ him somewhere as a servant. He was appointed to the stable; there he could do little harm. Joseph was made the keeper of the monastery mule.

And then a change came. Joseph set about his task since it was now clear that he could never be a Franciscan, at least he could be their servant. He said not a word in complaint; what had he to complain of? He told himself that all this was only what he might have expected; being what he was, he might consider himself fortunate to find any job at all entrusted to him. He asked for no relief; he took the clothes and the food they chose to give him; he slept on a plank in the stable, it was good enough for him. What was more, in spite of his dullness, perhaps because of it, Joseph had by nature a merry heart. However great his troubles, the moment a gleam of sunshine shone upon him he would be merry and laugh. The troubles were only his desert and were to be expected; when brighter times came he enjoyed them as one who had received a consolation wholly unlooked for, and wholly undeserved.

Gradually this became noticed. Friars would go down to the stable for one reason or another, and always Joseph was there to welcome them, apparently as happy as a lord. It was seen how little he thought of himself, how glad he was to serve; since he could not be a begging friar, sometimes in his free moments he went out and begged for them on his own account. His lightheartedness was contagious; his kindly tongue made men trust him; it was noticed how he was welcomed among the poorest of the poor, who saw better than others the man behind all his oddities. He might make a Franciscan after all. The matter was discussed in the community chapter; his case was sent up to a provincial council for favorable consideration; it was decided, not without some qualms, to give him yet another trial.

In this way Joseph was once more admitted to the Order, but what was to be done with him then? His superiors set him to his studies, in the hope that he might learn enough to be ordained, but the effort seemed hopeless. With all his good intentions he learnt to read with the greatest difficulty, and, says his biographer, his writing was worse. He could never expound a Sunday Gospel in a way to satisfy his professors; one only text seemed to take hold of him, and on that he could always be eloquent; speaking from knowledge which was not found in books. It was a text of St. Luke (xi, 27): “Beatus venter qui Te portavit.”

Minor Orders in those days were easily conferred, and even the subdiaconate; but for the diaconate and the priesthood a special examination had to be passed, in presence of the bishop himself. As a matter of form, but with no hope of success, Joseph was sent up to meet his fate. The bishop opened the New Testament at haphazard; his eye fell upon the text “Beatus venter qui Te portavit,” and he asked Joseph to discourse upon it. To the surprise of everyone present Joseph began, and it seemed as if he would never end; he might have been a Master in Theology lost in a favorite theme. There could be no question about his being given the diaconate.

When it was a question of the priesthood, the first candidates did so well that the remainder of the candidates, Joseph among them, were passed without examination and Joseph was ordained a priest in 1628. Deo gratias!

His virtues were such that he became a cleric at 22, a priest at 25, on March 4, 1628. Joseph still had little education, could barely read or write, but received such a gift of spiritual knowledge and discernment that he could solve intricate questions. During this period of his life, the spiritual consolations he had enjoyed since his childhood abandoned him. Later he wrote to a friend about that difficult time: “I complained a lot to God about God. I had left everything for Him, and He, instead of consoling me, delivered me to mortal anguish.”

He continued: “One day, when I was weeping and wailing in my cell, a religious knocked on my door. I did not answer, but he entered my room and said: ‘Friar Joseph, how are you?’

“‘I am here to serve you,’ I answered.

“‘I thought you did not have a habit,’ he continued.

“‘Yes, I have one, but it is falling apart,’ I responded.

“Then, the unknown religious gave me a habit, and when I put it on, all my despair disappeared immediately. No one ever knew who that religious was.”

There were many, by this time, besides the very poor who had come to realize the wonderful simplicity and selflessness of Joseph, hidden beneath his dullness and odd ways; a few had discovered the secret of his abstractedness, when he would lose himself in the labyrinth of God.

Nevertheless he remained a trial, especially to the practical-minded; to the end of his life he had to endure from them many a scolding. Often enough he would go out begging for the brethren, and would come home with his sack full, but without a sandal, or his girdle, or his rosary, or sometimes parts of his habit. His friends among the poor had taken them for keepsakes, and Joseph had been utterly unaware that they had gone. He was told that the convent could not afford to give him new clothes every day. “Oh! Father,” was his answer, “then don’t let me go out any more; never let me go out any more. Leave me alone in my cell to vegetate; it is all I can do.”

For indeed, as we have seen, Joseph had no delusions about himself; and his ordination did not make him think differently. True he was a priest, but everybody knew how he had received the priesthood. He could assume no airs on that account.

On the contrary, knowing what he was, he could only act accordingly. In spite of his priestly office, Joseph could only live the life he had lived before. He would slip down to the kitchen and wash up the dishes; he would sweep the corridors and dormitories; he would look out for the dirtiest work that others shirked, and would do it; when building was going on in the convent he would carry up the stones and mortar; if anyone protested, declaring that such work did not become a priest, Joseph would only reply to them: “What else can Brother Ass do?”, a name given him by his brothers in religion.

But now began that wonderful experience the like of which is scarcely to be paralleled in the life of any other saint. It was first in his prayer. Joseph’s absent-mindedness, from his childhood upwards, had not been only a natural weakness, it was due, in great part, to a wonderful gift of seeing God and the supernatural in everything about him, and he would become lost in the wonder of it all. Now when he was a friar, and a priest besides, the vision grew stronger; it seemed easier for him to see God indwelling in His creation than the material creation in which he dwelt. The realization became to him so vivid, so engrossing, that he would spend whole days lost in its fascination, and only an order from his superiors could bring him back to earth.

Joseph’s visions and ecstasies would come suddenly upon him anywhere; as it were from out of space the eyes of God would look at him, or on the face of nature the hand of God would be seen at work, disposing all things.

Joseph would stand still, exactly as the vision caught him, fixed as a statue, insensible as a stone, and nothing could move him. The brethren would use pins and burning embers to recall him to his senses, but nothing could he feel. When he did revive and saw what had happened, he would call these visitations fits of giddiness, and ask them not to burn him again. Once a prelate, who had come to see him on some business, noticed that his hands were covered with sores. Joseph could not hide them, nor could he hide the truth, but he had an explanation ready.

“See, Father, what the brethren have to do to me when the fits of giddiness come on. They have to burn my hands, they have to cut my fingers, that is what they have to do.” And Joseph laughed, as he so often laughed; but we suspect that it was laughter keeping back tears.

His life became a series of visions and ecstasies, which could be triggered any time or place by the sound of a church bell, church music, the mention of the name of God or of the Blessed Virgin or of a saint, any event in the life of Christ, the sacred Passion, a holy picture, the thought of the glory in heaven, etc. Yelling, beating, pinching, burning, piercing with needles – none of this would bring him from his trances, but he would return to the world on hearing the voice of his superior in the order.

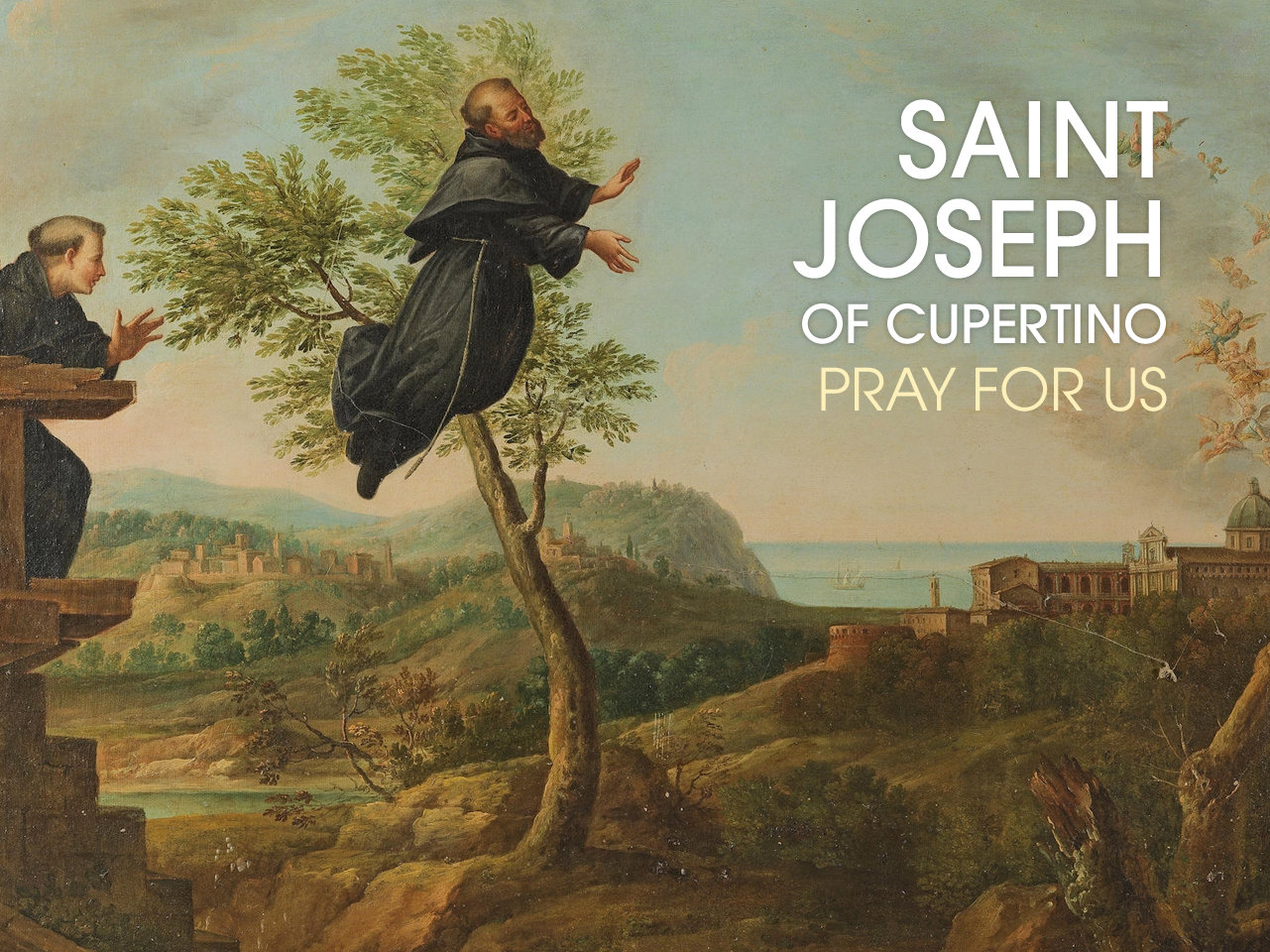

On October 4, 1630, the town of Cupertino held a procession on the feast day of Saint Francis of Assisi. Joseph was assisting in the procession when he suddenly soared into the sky, where he remained hovering over the crowd.

When he descended and realized what had happened, he became so embarrassed that he fled to his mother’s house and hid. This was the first of many flights, which soon earned him the nickname “The Flying Saint”.

Joseph’s life changed dramatically after this incident. His flights continued and came with increasing frequency. His superiors, alarmed at his lack of control, forbade him from community exercises, believing he would cause too great a distraction for the friary. For the fact was, Joseph could not contain himself. On hearing the names of Jesus or Mary, the singing of hymns during the feast of St. Francis, or while praying at Mass, he would go into a dazed state and soar into the air, remaining there until a superior commanded him under obedience to revive.

In the refectory, during a meal, Joseph would suddenly rise from the ground with a dish of food in his hands, much to the alarm of the brethren at table. When he was out in the country begging, suddenly he would fly into a tree. Once when some workmen were laboring to plant a huge stone cross in its socket, Joseph rose above them, took up the cross and placed it in the socket for them.

So concerned were Joseph’s brethren, they ordered him to be examined by the General of the Order. The Minister General could find no fault in Joseph. He took Joseph to see the Pope.

Joseph’s most famous flight allegedly occurred during the papal audience before Pope Urban VIII. When he bent down to kiss the Pope’s feet, he was suddenly filled with reverence for Christ’s Vicar on earth, and was lifted up into the air. Only when the Minister General of the Order, who was part of the audience, ordered him down was Joseph able to return to the floor.

Among other paranormal events associated with Joseph, he is said to have possessed the gift of healing. It is reported he once cured a girl who was suffering from a severe case of measles. Another story holds that an entire community suffering from a drought asked Joseph to pray for rain, which he did with success. He also dedicated himself to improving the spiritual lives of his fellow friars.

Not all of the friars whom Joseph lived with were well disposed towards him. Some superiors would scold Joseph for not accepting money and gifts offered to him for curing people, especially when they were members of the nobility. He would also find himself in trouble for returning home with a torn habit as a result of the people seeking relics who regarded him as a prophet and a saint.

Perhaps the most difficult time came when Joseph was the subject of an investigation by the Inquisition at Naples. Msgr. Joseph Palamolla accused Joseph of attracting undue attention with his “flights”, and claiming to perform miracles. On October 21, 1638, Joseph was summoned to appear before the Inquisition and, when he arrived, he was detained for several weeks. Joseph was eventually released when the judges found no fault with him.

Nervous and concerned about letting Joseph wander about at liberty with such powers and how that might upset ordered society, wanting to keep all of this hush-hush, Joseph’s superiors ordered him into seclusion. “Have I to go to prison?” he asked, as if he had been condemned. But in an instant he recovered. He knelt down and kissed the Inquisitor’s feet; then got into the carriage, smiling as usual as if nothing had happened.

After being cleared by the Inquisition, Joseph was sent to the Sacro Convento in Assisi. Though Joseph was happy to be close to the tomb of St Francis, he experienced a certain spiritual dryness. His flights came to a halt during this period.

Two years after his arrival at the Sacro Convento, Joseph was made an honorary citizen of Assisi and a full member of the Franciscan community. He lived in Assisi for another nine years. During this period Joseph was sought after by people (including ministers general, provincials, bishops, cardinals, knights and secular princes) who wanted to experience his divine consolation. He was happy to oblige, but the isolation of exile left him repressed. Believers were able to seek him out, but he was not allowed to preach or hear confessions, nor to join in the processions and festivities of feast days.

Over time, Joseph attracted a huge following. To stop this, Pope Innocent X decided to move Joseph from Assisi and place him in a secret location under the jurisdiction of the Capuchin friars in Pietrarubbia. Joseph was placed under strict orders to avoid writing letters, but he continued to attract throngs of people. This soon forced him to be moved to another location, this time to Fossombrone, which had little more success.

The ordeal finally ended when Pope Innocent X died, and the Conventual friars asked the newly elected Pope Alexander VIII to release Joseph from his exile and return him to Assisi. Alexander declined, and instead released Joseph to the friary in Osimo, where the Pope’s nephew was the local bishop. There, Joseph was ordered to live in seclusion and not speak to anyone except the Bishop, the Vicar General of the Order, his fellow friars, and, in case of a health crisis, a doctor. Joseph endured his ordeal with great patience. It is reported he did not even complain when a brother-cook neglected to bring him any food to his room for two days; this dull man whom no one could teach, and no one wanted, almost continually wrapt up in the vision of that which no man can express in words.

On August 10, 1663, Joseph became ill with a fever, but the experience filled him with joy. When asked to pray for his own healing he said, “No, God forbid!” He experienced ecstasies and flights during his last Mass which was on the Feast of the Assumption.

In early September, Joseph could sense that the end was near, so he could be heard mumbling, “The jackass has now begun to climb the mountain!” The ‘jackass’ was his own body.

Bedridden, there came constantly to Joseph’s lips the words of St. Paul: “Cupio dissolvi et esse cum Christo.” (Ph 1:23) Someone at the bedside spoke to him of the love of God; he cried out: “Say that again, say that again!” He pronounced the Holy Name of Jesus. He added: “Praised be God! Blessed be God! May the holy will of God be done!” The old laughter seemed to come back to his face; those around could scarcely resist the contagion. After receiving the last sacraments, a papal blessing, and reciting the Litany of Our Lady, Joseph Desa of Cupertino died on the evening of September 18, 1663.

He was buried two days later in the chapel of the Immaculate Conception before great crowds of people. Joseph was canonized on July 16, 1767, by Pope Clement XIII. In 1781, a large marble altar in the Church of St. Francis in Osimo was erected so that St. Joseph’s body might be placed beneath it; it has remained there ever since.

Even in the 17th century, there was interest in the unusual, and Joseph’s ecstasies in public caused both admiration and disturbance in the community. For 35 years he was not allowed to attend choir, go to the common refectory, walk in procession, or say Mass in church.

To prevent making a spectacle, he was ordered to remain in his room with a private chapel. He was brought before the Inquisition, and sent from one Capuchin or Franciscan house to another. But Joseph retained his joyous spirit, submitting to Divine Providence, keeping seven Lents of 40 days each year, never letting his faith be shaken. St Joseph of Cupertino, pray for us!

St. Joseph is the patron saint of those traveling by air, astronauts, and is the patron saint of pilots who fly for the NATO Alliance. He is the patron of paratroopers and those serving in the Air Force. He is also the patron of students taking exams. Cupertino, California, ranked as one of the most educated towns and world headquarters of Apple, Inc., is named after him. Cupertino boasts some of the highest ranked schools in the State of California, and has THE highest ranked highest ranked grammar school, Faria.

St. Joseph of Cupertino Church, stjoscup.org, is the Catholic parish in Cupertino, California. A life-sized bronze statue of St. Joseph in mid-flight was installed in the church prayer garden in 2006. The area where the city of Cupertino, California is today was first named in honor of St. Joseph of Cupertino on March 25, 1776, when Spanish explorers under Captain Juan Bautista de Anza camped in the area and named a small river for the Italian saint. The river is today known as Stevens Creek.

A 1962 film, “The Reluctant Saint”, starring Maximilian Schell and Ricardo Montalban was made about the life of St Joseph of Cupertino.

St. Joseph of Cupertino’s story was made into a children’s book called “The Little Friar Who Flew,” written by Patricia Lee Gauch, pictures by Tomie de Paola. It was published in 1980 by Peppercorn Publishers (soft cover) and G. P. Putnam’s Sons (hard cover), New York. ISBN (hardcover): 0-399-20714-7. ISBN (soft cover, large format): 0-399-20741-4.

A comic book, entitled The Flying Friar, was published by Speakeasy Comics in 2006, written by Rich Johnston, drawn by Thomas Nachlik, and edited by Tom Mauer. It is a fictionalization of the life of St Joseph, influenced heavily by the plotlines and characters of the Smallville TV series – St. Joseph is presented as a Clark Kent allegory, with his best friend turned worst enemy being the fictitious “Lux Luthor,” a supposed descendant of Martin Luther. (Mea culpa to the Lutherans on this distribution.)

Read the blog entries on this site reflecting prayers to and prayers answered through the intercession of St Joseph of Cupertino: http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=72. In the investigation preceding his canonization, 70 incidents of levitation were recorded.

Straight lines, see! 🙂 God is Great!!!!! Amen! Amen!

Prayer to St Joseph Cupertino

O Great St. Joseph of Cupertino, who while on earth did obtain from God the grace to be asked at your examination only the questions you knew, obtain for me a like favor in the examinations for which I am now preparing. In return I promise to make you known and cause you to be invoked.

Through Christ our Lord.

St. Joseph of Cupertino, pray for me.

O Holy Ghost, enlighten me

Our Lady of Good Studies, pray for me

Sacred Head of Jesus, Seat of divine wisdom, enlighten me.

Amen.

“Clearly, what God wants above all is our will which we received as a free gift from God in creation and possess as though our own. When a man trains himself to acts of virtue, it is with the help of grace from God from whom all good things come that he does this. The will is what man has as his unique possession.” – Saint Joseph of Cupertino, from the reading for his feast in the Franciscan breviary

-tomb of St Joseph of Cupertino, Osimo, Italy. Notice, please, how the angels hold aloft his sarcophagus.

Love,

Matthew