Perhaps the most famous of all medieval inquisitors, and certainly one of the most important and influential, Bernard Gui (1261-1331) is best known for his monumental inquisitor’s handbook, Practica inquisitionis heretice pravitatis (The Practice of the Inquisition of Heretical Depravity), written around 1324. In case you have an Inquisitorial (Inquisitional?) trial coming up, you can still pick up a copy at Amazon. (pssst…the have EVERYTHING!)

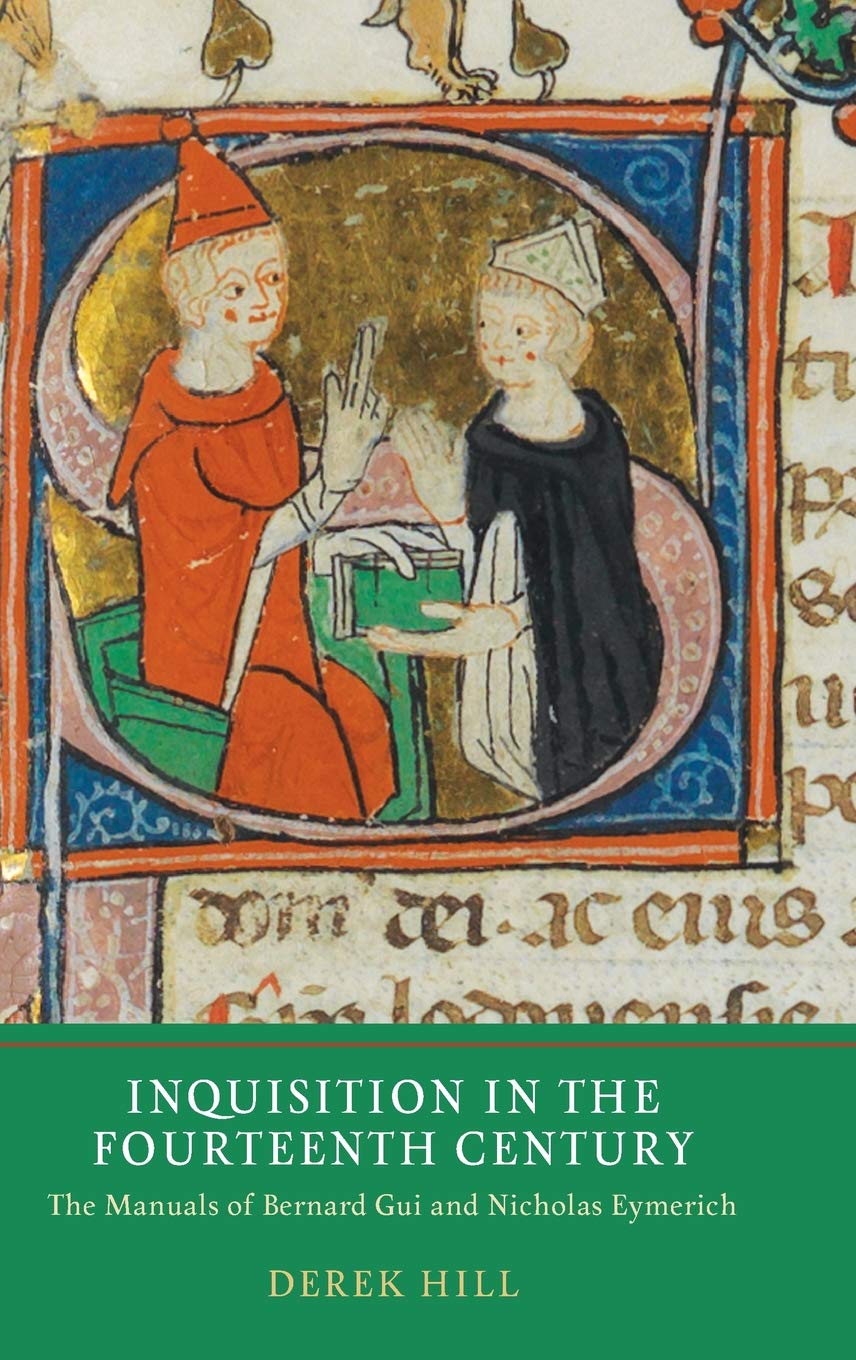

Although he never described anything like the full stereotype of witchcraft as it would appear in later centuries, he did include in this work several sections dealing with learned demonic magic, or necromancy, as well as more evidently popular forms of sorcery. The Practica inquisitionis became one of the most widely read of all medieval inquisitorial manuals, second only to the later Directorium inquisitorum (Directory of Inquisitors) of the Catalan inquisitor Nicolas Eymeric. Gui’s descriptions of sorcery thus seem very important, particularly in terms of shaping later clerical, and especially inquisitorial, thought on this subject.

Bernard Gui, or Bernard Guidoni was born in 1261 in Royères, France, and is one of the more well known Dominican inquisitors.

At the age of 19, Bernard entered the Order of Preachers and was made the prior of Albi ten years later. In 1306, he was sent to Avignon where he performed administrative service and served on two papal diplomatic missions. Bernard wrote a number of historical and theological works, which are more indicative of his primary historical significance as an administrator and historian rather than as an inquisitor. However, he is popularly known for his treatise on heresy, Practica Inquisitionis Heretice Pravitatis or “Conduct of the Inquisition into Heretical Wickedness” which contains instructions on the duties and rights of the inquisitor and how to approach the questioning of Manicheans, the Waldensians, the False Apostles, and the Beguines. Bernard was made bishop of Lodève, France in 1324, were he was noted for his energetic and skillful management. He died on December 30th 1331.

Modern scholars tend to view Bernard positively, as he reconciled many more people to the Church than he condemned. However, he does rank as one of the more zealous of inquisitors because Bernard viewed the inquisition as a kind of debate competition where the heretic is trying to conceal and hide his heresy, while the inquisitor is attempting to convince the audience that the heretic is merely putting on a show, trying to distract from their errors. This led to Bernard emphasizing the performative aspects of the inquisitor’s actions in an effort to win the hearts and minds of the audience (and hence the local community) so that they would stay loyal to the truth faith.

Gui oversaw trials which led to over 900 guilty verdicts in fifteen years of office. People convicted of heresy during the time of the Inquisition were turned over to the secular arm (nobles and city leaders) for punishment. The Church was not allowed to shed blood, but the rack and pear were not considered blood spilling. Out of all those convicted during examination by Gui, 42 were executed.

Between 1307 and 1323, at the behest of Pope Clement V and Pope John XXII, Gui served as the chief inquisitor of Toulouse. He also assisted the inquisitors of Carcassone, Geoffrey of Ablis and his successor Beaune, and the bishop of Pamiers, Jacques Fournier (later Pope Benedict XII). Gui’s inquisitorial work took place in the Languedoc, a region that remained a “stronghold of heresy”, in particular Catharism, despite the church’s repeated efforts in the area throughout the thirteenth century (such as the Albigensian Crusade of 1209–1229).

In this capacity Gui travelled the region, meeting with local clergy and officials, publicly preaching about the danger of heretical teachings, and inviting those guilty of heretical sins to voluntarily confess in exchange for light penance. He then interrogated those who had been accused of heretical activity by penitents but failed to come forward voluntarily, with the secular authorities enlisted to apprehend and, if necessary, torture the accused. (A papal bull of 1252 permitted torture in cases in which there were “enough partial proofs to indicate that a full proof—a confession—was likely, and no other full proofs were available”, although “a confession made after or under torture had to be freely repeated the next day without torture or it would have been considered invalid”.)

The inquisitor would then hold a ‘general sermon’ (sermo generalis), assembling the local populace and publicly declaring the names of those judged guilty of the sin of heresy and their concomitant penances. Typical penalties included fasting, scourging, pilgrimage, the confiscation of property, or the wearing of large yellow crosses (with “the arms of the crosses [to be] two-and-a-half fingers in breadth, two-and-a-half palms in height, and two palms in width”) on the front and back of outer clothing. As canon law prohibited the clergy from spilling blood, those who refused to repent or who had relapsed into heresy were handed over to the secular authorities for punishment, typically execution by burning at the stake.

During his tenure Gui held eleven such ‘general sermons’ in the cathedral of St Stephen in Toulouse and the cemetery of St John the Martyr in Pamiers, at which he judged 627 individuals guilty of heresy. A further nine individuals were also judged guilty at smaller events. In total, the tribunals headed by Gui convicted 636 individuals of 940 counts of heresy. Recent research has determined that no more than 45 of the individuals convicted by Gui (approximately 7% of the total) were executed, while 307 were imprisoned, 143 ordered to wear crosses, and nine sent on compulsory pilgrimages. The Inquisition kept excellent records. It was required to.

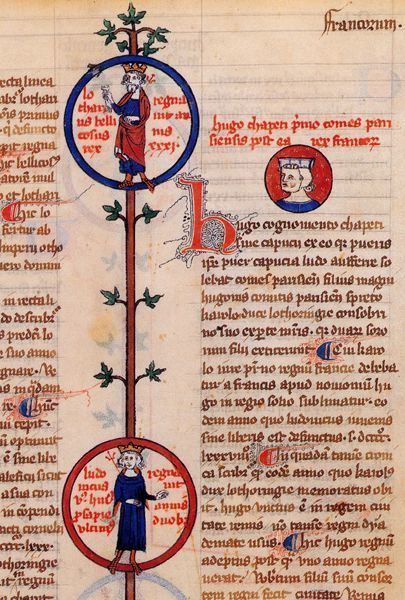

-illustrations from a copy of Gui’s Arbor genealogiae regum francorum produced in the 1330s, showing the Carolingian kings Lothair and Louis V

-by Steve Weidenkopf

“The Frenchman Bernard Guidonis (usually shortened to Gui) was born twenty years after the death of Pope Gregory IX (r. 1227-1241), but that pontificate shaped the course of Bernard’s life. In 1231, Gregory IX promulgated the bull Ille humani generis, wherein he established the procedures for papally appointed clergy as inquisitors charged with preserving orthodox Catholic beliefs and teachings throughout Christendom.

Not much is known about Bernard’s early life, but he enters the story of the Church in the late thirteenth century, when, as a young man, he joined St. Dominic’s Order of Preachers. After profession of his final vows, Bernard continued his studies and became a teacher for fifteen years. The order recognized Bernard’s brilliance and his humble and patient demeanor and sent him to the Dominican house in the town of Albi in 1306 as a lecturer in theology.

-14th-century illustration of Gui receiving a blessing from Pope John XXII

Although it had been more than seventy-five years since the end of the bloody Albigensian Crusade, called by Pope Innocent III to eradicate the heresy of the Cathars (or Albigensians)—who taught a form of Gnosticism, wherein material things are evil and spiritual things are good—erroneous teachings still held sway in the region. What was needed was an inquisition—and for there to be an inquisition, there had to be dedicated inquisitors.

Appointment as a papal inquisitor required candidates to be at least forty years old, trained in theology, and notable for a virtuous life. The inquisitor was expected to protect the unity and security of the Church and society from the poison of heresy. As a matter of charity, the inquisitor worked to save the jeopardized soul of the heretic and to reconcile the errant to the Church.

Bernard met all these criteria. So he was appointed an inquisitor, and he spent the next several decades prosecuting heretics, including Albigensians, the False Apostles, the Fraticelli, and the Waldensians.

Bernard wrote about his dealings with the Waldensians, named for Peter Waldo of Lyons, a merchant who, in 1170, decided to sell his goods, give to the poor, and abandon his family. His message attracted followers, and those who joined him began calling themselves the Humiliati or the Poor Men of Lyons. The archbishop of Lyons prohibited their preaching, but to no avail. The Waldensians taught contempt for Church authority, denied the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, forbade the taking of oaths, and argued against the death penalty as criminal punishment.

In his book The Waldensian Heretics, Bernard provided insight for his fellow inquisitor, derived from personal experience, on how to handle these crafty disruptors. Bernard illustrated how difficult it was to interrogate Waldensians because of “the deception and duplicity with which they answer questions.” He provided an example of an interrogation with a heretic: “When he is asked if he knows why he has been arrested, he answers very sweetly and with a smile, ‘My Lord, I should be glad to learn the reason from you.’ Asked about the faith which he holds and believes, he answers, ‘I believe everything that a good Christian ought to believe.’ Questioned as to whom he considers a good Christian, he replies, ‘He who believes as Holy Church teaches him to believe.’ When he is asked what he means by ‘Holy Church,’ he answers, ‘My lord, that which you say and believe is the Holy Church.’ If you say to him, ‘I believe that the Holy Church is the Roman Church, over which the lord pope rules; and under him, the prelates,’ he replies, ‘I believe it.’ Meaning that he believes that you believe it.”

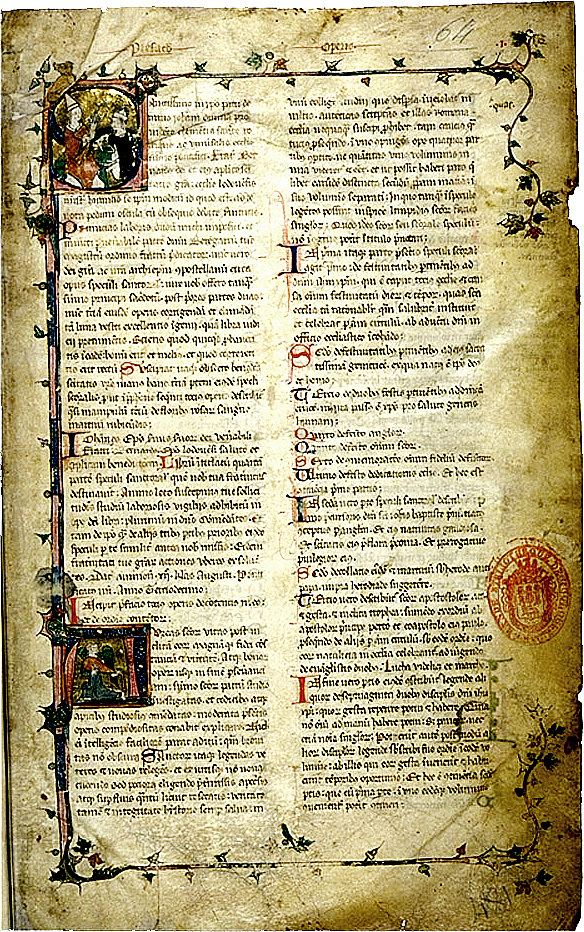

Bernard’s extensive career and experience with different heretical groups, coupled with his scholarly nature, led him to write a manual for inquisitors known as the Practica. Divided into five parts, the Practica was a handbook containing procedures for the arrest of suspects of heresy, sample inquisitorial edicts and decrees, examples of sentences, a treatise on the duty of inquisitors, a collection of papal documents concerning heresy and inquisitors, and descriptions of various heretics and how to recognize them. In describing the ideal inquisitor, Bernard stressed piety and humility as key attributes. He believed also that an inquisitor should be zealous for the Faith and the salvation of souls, in control of his emotions, unyielding, free from malice and anger, not motivated by cruelty or revenge, wary of laziness and gullibility, and imbued with a spirit of compassion. Moreover, Bernard emphasized that each inquisitorial case must be considered on its own merits and by its own unique circumstances and characteristics. No two investigations were alike.

During his decades-long and impressive inquisitorial career, Bernard passed 930 judgments in heresy cases, an average of fifty-four per year or a little more than one a week. Most of his cases resulted in imprisonment or penitential sentences, with only forty-two obstinate heretics remanded to the secular authority for capital punishment. The resolute Bernard illustrated that the focus of the medieval inquisitors was the salvation of the souls of those who embraced false teachings through a patient and charitable investigation. He embodied the attributes of the perfect inquisitor, with justice and mercy at the forefront. Bernard did not seek appointment as an inquisitor, but he accepted the position with humility and strove diligently to protect the faithful from dangerous heretical teachings that threatened their eternal salvation.

Although known mostly for his career as an inquisitor, Bernard was also a historian and author of works on the liturgy and the lives of the saints. Pope John XXII (r. 1316–1334) made Bernard a bishop. He spent the remainder of his days focused on the pastoral care of the people of God entrusted to him. and he went to his eternal reward.”

He died in his episcopal residence at Lauroux castle on 30 December 1331, and following his funeral in Lodève Cathedral his body was transported to Limoges to be buried in the church of the Dominican monastery. However, his tomb was looted during the late-sixteenth-century Wars of Religion.

Love & truth,

Matthew