-by Joseph Pearce

“As a word, “modernism” has several definitions, or, to put the matter the other way round, there are a number of things to which the label “modernism” has been appended. As such, and as usual, it is important to define our terms before we proceed any further with a discussion of this crucially important word, and crucially perilous thing.

A cursory search for the word on the worldwide web will reveal its definition, on Wikipedia, as “a philosophical movement that, along with cultural trends and changes, arose from wide-scale and far-reaching transformations in Western society in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.” Further reading reveals that “modernism,” according to Wikipedia, is primarily a movement in the arts, flourishing in the early twentieth century, which sought to break with the forms and traditions of the past through innovations, such as the stream-of-consciousness in literature, atonality in music, and the abstract in art. It is, or was, self-consciously cynical, viewing reality, as it perceived it, as an absurdity warranting parody.

Although this definition serves to illustrate one particular aspect or manifestation of modernism, it is really only an accidental byproduct of real Modernism. Real or primal Modernism, the mother of all other modernisms, including the artistic movement of the same name, is better understood if we see it in the light of the heresy of modernism as condemned by St. Pius X in his 1907 encyclical Pascendi dominici gregis.

In this encyclical Pius X condemned those who sought to bring the beliefs of the Catholic Church “up to date” in the light (or shadow) of recent developments in philosophy. It is this “up-to-dateness” which is the real spirit of Modernism. It is the presumption that whatever is up-to-date is better than whatever is deemed to be out-of-date. At the root of this presumption is a belief that the present is superior to the past and that, by logical extension, the future will be better than the present. It is what might be called optimistic presumption, or the prejudice of optimism.

As with other forms of prejudice, it tends to look down its supercilious nose at its neighbors, which is why those who are optimists in terms of their belief in inexorable progress, i.e. their belief that things are always getting better, are also and always pessimists about the collective inheritance of human experience and knowledge, which is the history of civilization. To such prejudiced optimists, who prefer to call themselves progressives, the past is populated with barbarians and savages who should be condemned for their perceived ignorance, and treated with the contempt that such unenlightened untermenschen deserve. They are not “up-to-date” and, as such, need not be seen as our equals.

Those who believe that something is good merely because it is “modern” are guilty of what C. S. Lewis called chronological snobbery. They are, in Chesterton’s judgment, ungrateful cads who kick down the ladder by which they’ve climbed. Modernists are, however, not merely cads or snobs; they are idolaters. They worship a false god. The god they worship is the Time-Spirit, or what the Germans call the Zeitgeist, or what might better be called the Spirit of the Age. The absurdity is that they worship a god which is as changeable as the wind or the weather—and as potentially catastrophic and deadly.

A quick glance at some of the past century’s modernists will serve to show the absurdity of worshiping this changeable god.

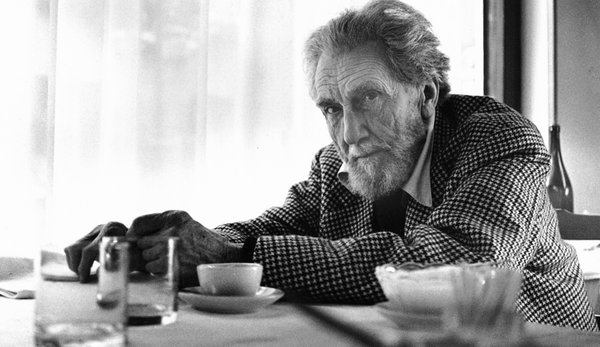

Take, for example, Ezra Pound, the godfather of twentieth-century modernism, whose injunction to “Make it new!” became the mantra of the modernist movement. He became enamoured of Italian fascism, seeing it as the creed of the future. It might seem silly now to believe that anyone could take Mussolini seriously but there was a time when fascism was de rigueur and very much new and up-to-date. Nor was Ezra Pound alone in his admiration for Italian fascism. The futurist movement which, as its name implied, idolized all that was new, up-to-date and modern, became inextricably connected to Mussolini’s ideology. Fascism was seen as the faith of the future because of its faith in the future. Meanwhile, the Russian futurists put themselves at the service of the exciting new ideas of communism, becoming part of the new Soviet Union’s propaganda machine.

The irony is, of course, that all of this modernist worship of the future seems terribly out-of-date today. The fact is that to be up-to-date today condemns us to being out-of-date tomorrow, or, as C. S. Lewis liked to say, fashions are always coming and going, but mostly going.

To worship the spirit of our own age is to condemn ourselves to looking very silly to future ages. The test, therefore, is not to be in step with our own times but to be in step with all-times, the latter of which is to march in time with that which is always timely because it is perennially timeless.

What is Modernism? It is the worship of the false gods of fashion instead of the true God of tradition. It is the enemy of all who seek the Way, the Truth and the Life. It is the enemy of all who do not want a church that will move with the world but a church that will move the world. It is to choose the Spirit of the Age instead of the Spirit of All Ages. It is to choose the Spirit that Ages instead of the Spirit that Never Ages. It is to choose the Time-Spirit and not the Holy Spirit. Modernism, to put the matter bluntly, is madness.”

Love,

Matthew