As February is thought of as a month of love, it is terribly fitting, IMHO, to remember this great lover and poet, and most importantly, as always, The Object of his love.

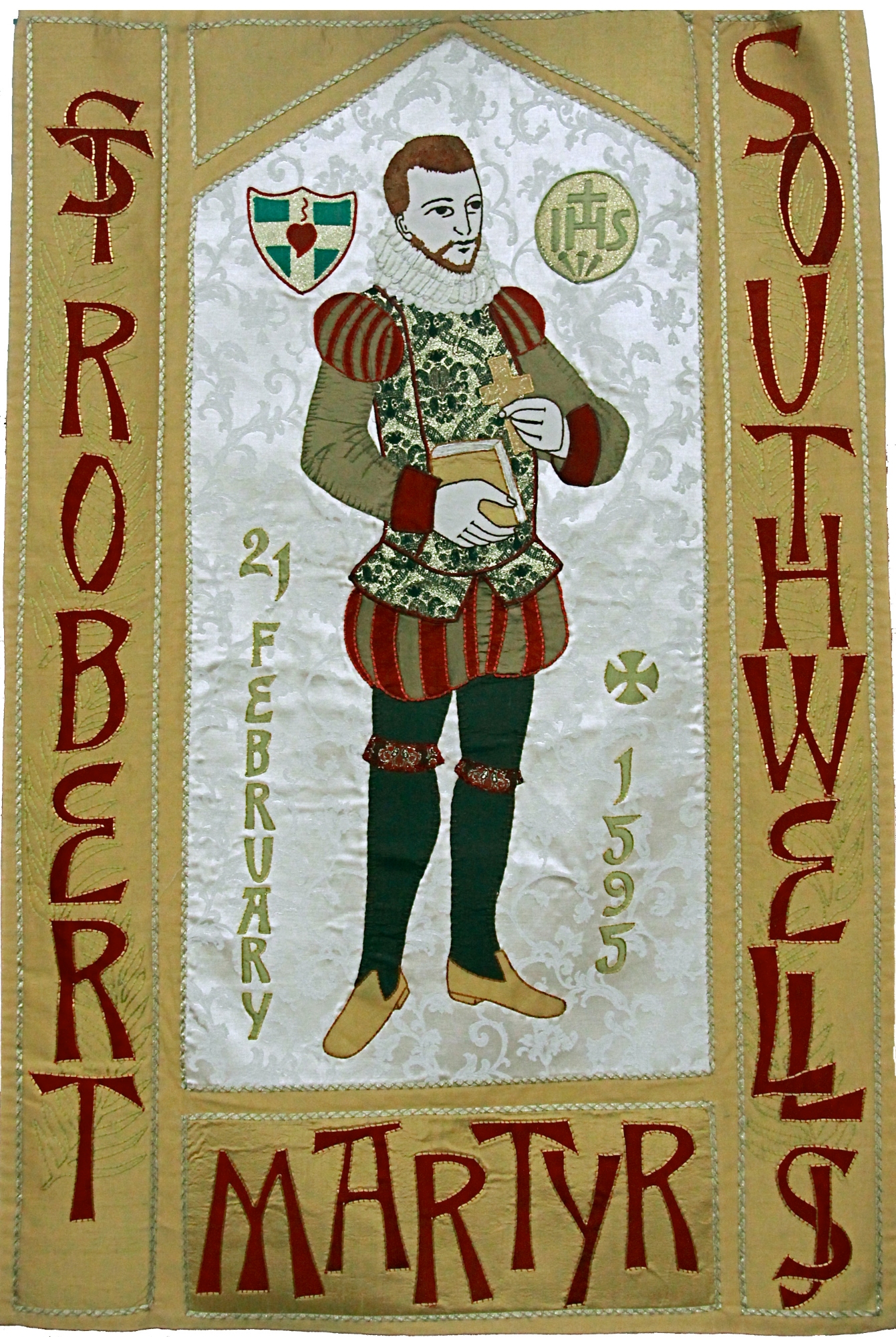

Robert Southwell was born at Horsham St. Faith’s, Norfolk, England, in 1561, the third of eight children. His grandfather, Sir Richard Southwell, had been a wealthy man and a prominent courtier in the reign of Henry VIII, and the family remained among the elite of the land. He was so beautiful as a young boy that a gypsy stole him. He was soon recovered by his family and became a short, handsome man, with gray eyes and red hair.

It was Richard Southwell who in 1547 had brought the poet Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, to the block, and Surrey had vainly begged to be allowed to “fight him in his shirt”. Curiously enough their respective grandsons, Robert Southwell and Philip, Earl of Arundel, were to be the most devoted of friends and fellow-prisoners for the Faith. On his mother’s side the Jesuit was descended from the Copley and Shelley families, whence a remote connection may be established between him and the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Despite their Catholic sympathies, the Southwells had profited considerably from King Henry VIII’s Suppression of the Monasteries.

Even as a child, Southwell was distinguished by his attraction to the old religion. Protestantism had come to England, and it was actually a crime for any Englishman who had been ordained as a Catholic priest to remain in England more than forty days at a time. In order to keep the faith alive, William Allen had opened a school at Douai, where he made a Catholic translation of the Bible, the well-known Douai version. Southwell attended this school and asked to be admitted into the Jesuits. At first the Jesuits refused his application, but eventually his earnest appeals moved them to accept him. He wrote to the Jesuits “How can I but waste in anguish and agony that I find myself disjoined from that company, severed from that Society, disunited from that body, wherein lyeth all my life, my love, my whole heart and affection.” (Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, Anglia 14, fol. 80, under date 1578). He was ordained a priest in 1584. Two years later, at his own request, he was sent as a missionary to England, well knowing the dangers he faced. A poet and a scholar, his poetry would have a profound influence on the moral climate of the age.

A spy reported to Sir Francis Walsingham the Jesuits’ landing on the east coast in July, but they arrived without molestation at the house at Hackney of William Vaux, 3rd Baron Vaux of Harrowden. For six years they kept him under surveillance. He assumed the last alias “Cotton” and found employment as a chaplain to Ann Howard, Lady Arundel, her husband being accused of treason for being a Catholic and in prison. Southwell wrote a prose elegy, Triumphs over Death, to the earl to console him for a sister’s premature death. Although Southwell lived mostly in London, he traveled in disguise and preached secretly throughout England, moving from one Catholic family to another. His downfall and capture came about when he became friendly with a Catholic family named Bellamy.

Southwell was in the habit of visiting the house of Richard Bellamy, who lived near Harrow and was under suspicion on account of his connection with Jerome Bellamy, who had been executed for sharing in Anthony Babington’s plot, which intended to assassinate the Queen and place Mary, Queen of Scots, on the English throne.

One of the daughters, Anne Bellamy, was arrested and imprisoned in the gatehouse of Holborn for being linked to the situation. Having been interrogated and raped by Richard Topcliffe, the Queen’s chief priest-hunter and torturer, she revealed Southwell’s movements and Southwell was immediately arrested. When Bellamy became pregnant by Topcliffe in 1592, she was forced to marry his servant to cover up the scandal.

Southwell was first taken to Topcliffe’s own house, adjoining the Gatehouse Prison, where Topcliffe subjected him to the torture of “the manacles”. He remained silent in Topcliffe’s custody for forty hours. The queen then ordered Southwell moved to the Gatehouse, where a team of Privy Council torturers went to work on him. When they proved equally unsuccessful, he was left “hurt, starving, covered with maggots and lice, to lie in his own filth.” After about a month he was moved by order of the Council to solitary confinement in the Tower of London. According to the early narratives, his father had petitioned the queen that his son, if guilty under the law, should so suffer, but if not should be treated as a gentleman, and that as his father he should be allowed to provide him with the necessities of life. No documentary evidence of such a petition survives, but something of the kind must have happened, since his friends were able to provide him with food and clothing, and to send him the works of St. Bernard and a Bible. His superior St Henry Garnet, SJ, later smuggled a breviary to him. He remained in the Tower for three years, under Topcliffe’s supervision.

Tortured thirteen times, he nonetheless refused to reveal the names of fellow Catholics. During his incarceration, he was allowed to write. His works had already circulated widely and seen print, although their authorship was well known and one might have expected the government to suppress them. Now he added to them poems intended to sustain himself and comfort his fellow prisoners. He wrote “Not where I breathe, but where I love, I live; Not where I love, but where I am, I die.” He was so ill treated, his father petitioned the Queen that he be brought to trial.

February 21, 1595, Southwell was brought to Tyburn, where he was to be hung and then quartered for treason, although no treasonous word or act had been shown against him. It was enough that he held a variation of the Christian faith that frightened many Englishmen because of rumors of Catholic plots. He addressed the crowd gathered, “I am come hither to play out the last act of this poor life.” He prayed for the salvation of the Queen and country.

Execution of sentence on a notorious highwayman had been appointed for the same time, but at a different place — perhaps to draw the crowds away — and yet many came to witness Southwell’s death. Eyewitness accounts, both Catholic and Protestant, are unanimous in describing Southwell as both gracious and prayerful in his final moments.

When cut loose from the halter that tied him to the cart, he wiped his brow with a handkerchief and tossed the “sudarium” into the crowd, the first of what would become his relics. When asked if he would like to speak, Southwell crossed himself and first spoke in Latin, quoting Romans 14:8:“Sive uiuimus, Domino uiuimus, sive morimur, Domino morimur, ergo uiuimus, sive morimur, Domini sumus.” (If we live, we live in the Lord. If we die, we die in the Lord. Therefore, whether we live or we die, we are in the Lord.) The sheriff made to interrupt him; but, was allowed to continue for some time. He then addressed himself to the crowd, saying he died a Catholic and a Jesuit, offenses for which he was not sorry to die. He spoke respectfully of the Queen, and asked her forgiveness, if she had found any offense in him.

Then, after the hangman stripped him down to his shirt and tightened the noose around his neck, Robert Southwell spoke his last words (found in both Psalm 30 and the Gospel of Luke),“In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum. Redemisti me, Domine Deus veritatis,” while repeatedly making the sign of the cross. “Into your hands, Lord, I commend my spirit. You have redeemed me, Lord God of truth.”

At the third utterance of these words, the cart rolled away and Southwell hung from his neck. Those present forbade the hangman cutting him down to further the cruelties of drawing and quartering before Southwell was dead. He hung in the noose for a brief time, making the sign of the cross as best he could. As the executioner made to cut him down, in preparation for disembowelling him while still alive, Lord Mountjoy and some other onlookers tugged at his legs to hasten his death. Yet, despite their efforts, according to one account, he was still breathing when cut down. When the hangman lifted Southwell’s head up before the crowd, no one cried “Traitor.” Even a pursuivant present admitted he had never seen a man die better.

Southwell’s writings, both in prose and verse, were extremely popular with his contemporaries, and his religious pieces were sold openly by the booksellers though their authorship was known. Imitations abounded, and Ben Jonson declared of one of Southwell’s pieces, The Burning Babe (below), that to have written it he would readily forfeit many of his own poems. Mary Magdalene’s Tears, the Jesuit’s earliest work, licensed in 1591, probably represents a deliberate attempt to employ in the cause of piety the euphuistic prose style, then so popular. Triumphs over Death, also in prose, exhibits the same characteristics; but this artificiality of structure is not so marked in the Short Rule of Good Life, the Letter to His Father, the Humble Supplication to Her Majesty, the Epistle of Comfort and the Hundred Meditations. Southwell’s longest poem, St. Peter’s Complaint (132 six-line stanzas), is imitated, from the Italian Lagrime di S. Pietro of Luigi Tansillo. This with some other smaller pieces was printed, with license, in 1595, the year of his death. Another volume of short poems appeared later in the same year under the title of Maeoniae. Perhaps no higher testimony can be found of the esteem in which Southwell’s verse was held by his contemporaries than the fact that, while it is probable that Southwell had read Shakespeare, it is practically certain that Shakespeare had read Southwell and imitated him.

-Line engraving by Matthaus Greuter (Greuther) or Paul Maupin, published 1608, frontispiece to St Peter’s Complaint.

“The Chief Justice asked how old he was, seeming to scorn his youth. He answered that he was near about the age of our Saviour, Who lived upon the earth thirty-three years; and he himself was as he thought near about thirty-four years. Hereat Topcliffe seemed to make great acclamation, saying that he compared himself to Christ. Mr. Southwell answered, ‘No he was a humble worm created by Christ.’ ‘Yes,’ said Topcliffe, ‘you are Christ’s fellow.'”—Father Henry Garnet, “Account of the Trial of Robert Southwell.” Quoted in Caraman’s The Other Face, page 230.

Southwell: I am decayed in memory with long and close imprisonment, and I have been tortured ten times. I had rather have endured ten executions. I speak not this for myself, but for others; that they may not be handled so inhumanely, to drive men to desperation, if it were possible.

Topcliffe: If he were racked, let me die for it.

Southwell: No; but it was as evil a torture, or late device.

Topcliffe: I did but set him against a wall. (The “Topciliffe Rack” was vertical, against a wall, not horizontal, adding the victim’s own weight to his pain, with never a relief.)

Southwell: Thou art a bad man.

Topcliffe: I would blow you all to dust if I could.

Southwell: What, all?

Topcliffe: Ay, all.

Southwell: What, soul and body too?

The Burning Babe

As I in hoary winter’s night

Stood shivering in the snow,

Surprised I was with sudden heat,

Which made my heart to glow;

And lifting up a fearful eye,

To view what fire was near,

A pretty Babe all burning bright

Did in the air appear;

Who, scorched with excessive heat,

Such floods of tears did shed,

As though His floods should quench His flames,

With which His tears were fed.

“Alas,” quoth He, “but newly born,

In fiery heats I fry,

Yet none approach to warm their hearts,

Or feel my fire, but I;

“My faultless breast the furnace is,

The fuel, wounding thorns:

Love is the fire, and sighs the smoke,

The ashes, shame and scorn;

“The fuel Justice layeth on,

And Mercy blows the coals,

The metal in this furnace wrought

Are men’s defiled souls,

“For which, as now on fire I am

To work them to their good,

So will I melt into a bath,

To wash them in My blood.”

With this he vanish’d out of sight,

And swiftly shrunk away,

And straight I called unto mind,

That it was Christmas day.

-Robert Southwell, SJ

A VALE OF TEARS.

By Robert Southwell, SJ

A vale there is, enwrapt with dreadful shades,

Which thick of mourning pines shrouds from the sun,

Where hanging cliffs yield short and dumpish glades,

And snowy flood with broken streams doth run.

Where eye-room is from rock to cloudy sky,

From thence to dales with stony ruins strew’d,

Then to the crushèd water’s frothy fry,

Which tumbleth from the tops where snow is thaw’d.

Where ears of other sound can have no choice,

But various blust’ring of the stubborn wind

In trees, in caves, in straits with divers noise;

Which now doth hiss, now howl, now roar by kind.

Where waters wrestle with encount’ring stones,

That break their streams, and turn them into foam,

The hollow clouds full fraught with thund’ring groans,

With hideous thumps discharge their pregnant womb.

And in the horror of this fearful quire

Consists the music of this doleful place;

All pleasant birds from thence their tunes retire,

Where none but heavy notes have any grace.

Resort there is of none but pilgrim wights,

That pass with trembling foot and panting heart;

With terror cast in cold and shivering frights,

They judge the place to terror framed by art.

Yet nature’s work it is, of art untouch’d,

So strait indeed, so vast unto the eye,

With such disorder’d order strangely couch’d,

And with such pleasing horror low and high,

That who it views must needs remain aghast,

Much at the work, more at the Maker’s might;

And muse how nature such a plot could cast

Where nothing seemeth wrong, yet nothing right.

A place for mated mindes, an only bower

Where everything do soothe a dumpish mood;

Earth lies forlorn, the cloudy sky doth lower,

The wind here weeps, here sighs, here cries aloud.

The struggling flood between the marble groans,

Then roaring beats upon the craggy sides;

A little off, amidst the pebble stones,

With bubbling streams and purling noise it glides.

The pines thick set, high grown and ever green,

Still clothe the place with sad and mourning veil;

Here gaping cliff, there mossy plain is seen,

Here hope doth spring, and there again doth quail.

Huge massy stones that hang by tickle stays,

Still threaten fall, and seem to hang in fear;

Some wither’d trees, ashamed of their decays,

Bereft of green are forced gray coats to wear.

Here crystal springs crept out of secret vein,

Straight find some envious hole that hides their grace;

Here searèd tufts lament the want of rain,

There thunder-wrack gives terror to the place.

All pangs and heavy passions here may find

A thousand motives suiting to their griefs,

To feed the sorrows of their troubled mind,

And chase away dame Pleasure’s vain reliefs.

To plaining thoughts this vale a rest may be,

To which from worldly joys they may retire;

Where sorrow springs from water, stone and tree;

Where everything with mourners doth conspire.

Sit here, my soul, main streams of tears afloat,

Here all thy sinful foils alone recount;

Of solemn tunes make thou the doleful note,

That, by thy ditties, dolour may amount.

When echo shall repeat thy painful cries,

Think that the very stones thy sins bewray,

And now accuse thee with their sad replies,

As heaven and earth shall in the latter day.

Let former faults be fuel of thy fire,

For grief in limbeck of thy heart to still

Thy pensive thoughts and dumps of thy desire,

And vapour tears up to thy eyes at will.

Let tears to tunes, and pains to plaints be press’d,

And let this be the burden of thy song,—

Come, deep remorse, possess my sinful breast;

Delights, adieu! I harbour’d you too long.

St Robert Southwell, SJ,’s Prayer for the Church:

“We therefore are under an obligation to be the light of the world by the modesty of our behaviour, the fervour of our charity, the innocence of our lives, and the example of our virtues.

Thus shall we be able to raise the lowered prestige of the Catholic Church, and to build up again the ruins that others by their vices have caused. Others by their wickedness have branded the Catholic Faith with a mark of shame, we must strive with all our strength to cleanse it from its ignominy and to restore it to its pristine glory. Amen.”

A Child My Choice

-by St. Robert Southwell

Let folly praise that fancy loves, I praise and love that Child

Whose heart no thought, whose tongue no word, whose hand no deed defiled.

I praise Him most, I love Him best, all praise and love is His;

While Him I love, in Him I live, and cannot live amiss.

Love’s sweetest mark, laud’s highest theme, man’s most desired light,

To love Him life, to leave Him death, to live in Him delight.

He mine by gift, I His by debt, thus each to other due;

First friend He was, best friend He is, all times will try Him true.

Though young, yet wise; though small, yet strong; though man, yet God He is:

As wise, He knows; as strong, He can; as God, He loves to bless.

His knowledge rules, His strength defends, His love doth cherish all;

His birth our joy, His life our light, His death our end of thrall.

Alas! He weeps, He sighs, He pants, yet do His angels sing;

Out of His tears, His sighs and throbs, doth bud a joyful spring.

Almighty Babe, whose tender arms can force all foes to fly,

Correct my faults, protect my life, direct me when I die!

Love,

Matthew