What can one person do? Certainly little in the modern world? Right? Certainly? This excuse is regularly used to avoid challenging questions one’s conscience may pose. The cost is one’s mental health and, possibly, one’s soul.

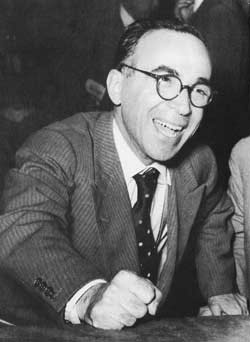

Giorgio La Pira was a charismatic and popular politician – the type of big city civic character who might seem familiar to Americans. What distinguishes La Pira is that this three-time mayor of Florence may well have been a saint. Governing in the 1950’s and 60’s he had an overriding concern for the poor, was a defender of the rights of workers and, later on, became an international apostle of peace.

On April 26, 2004, Italy celebrated the centenary of Giorgio La Pira. On that occasion, in a meeting with representatives from the National Association of Italian Municipalities, Pope John Paul II praised the former mayor of Florence as a man who “set forth with firmness his ideas as a believer and as a man who loved peace, inviting his interlocutors to a common effort to promote this basic good in various spheres: in society, politics, the economy, cultures and among religions.” Eighteen years earlier, in 1986, the formal process for the cause of the beatification of Giorgio La Pira began.

Even before his death, Giorgio La Pira was already considered a living saint by some in Italy. His clothes were alleged to have miraculous healing powers. Amintore Fanfani, La Pira’s friend and fellow Christian Democrat, was reported to have used an old hat of La Pira’s to cure minor illnesses suffered by his children. Who was this man?

Giorgio La Pira was born on January 09, 1904 in Pozzallo, a town in the province of Ragusa in Sicily. Born the eldest of six children, La Pira’s family was not wealthy. His father, Gaetano, worked in a packing house. However, like many Italian children, La Pira was brought up in a Catholic household that valued education. After moving to Messina to live with an uncle, La Pira received both a traditional education in the Classics as well as a business education, receiving a degree in accounting. Law school was the next step in an academic career that would eventually see the cheerful Sicilian awarded the Chair of Roman Law at the University of Florence in 1933.

While beloved by his students, La Pira eventually ran afoul of Italy’s Fascist regime. Having helped found the anti-fascist magazine Principles in 1939, La Pira became a target of Mussolini’s police, prompting La Pira to seek refuge in the Vatican City where he worked for L’Osservatore Romano, the newspaper of the Holy See. After the end of World War II, La Pira played an important role in shaping the future of the Italian Republic. As part of the Constituent Assembly, La Pira helped craft the new Italian constitution, standing firmly in favor of the legal indissolubility of the family and championing the authority of fathers within the family. In 1948, La Pira went to work for the government of Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi as Undersecretary of Labor in the Ministry of Employment and Social Insurance.

During his period in the national government, La Pira became associated with the left-wing of the Christian Democratic Party, along with Giuseppe Dossetti, Amintore Fanfani, and Giuseppe Lazzati. Known as the “Little Professors” because of their impressive academic credentials and Christian idealism, the friends founded the journal Cronache Sociali, a left-leaning journal of Christian social thinking. La Pira’s writings on economics were heavily influenced by John Maynard Keynes and other British sources including Stafford Cripps and the Labour Party in general. For La Pira and many of his allies on the left-wing of the Christian Democratic Party, Clement Attlee’s Labour government in Great Britain was the model that post-war Italy ought to follow on questions of economics.

When La Pira became Mayor of Florence in 1951, he brought with him many of the economic ideas he developed while writing for the Cronache Sociali and working in the national government on problems of unemployment and other socio-economic issues. These ideas would be put to the test in a concrete fashion when La Pira was faced with a city suffering from high unemployment and a housing shortage. Wasting little time, La Pira’s administration burst into action, developing a number of public works projects designed to alleviate the city’s unemployment problem. Under La Pira’s watch, bridges destroyed during the war were rebuilt, water works and public transportation systems were repaired or built, low-cost public housing was constructed for the homeless residents of the city, and various artistic and cultural programs were developed. La Pira’s vision for Florence was a city of self-sufficient neighbourhoods with a vibrant cultural life.

Of course, La Pira’s administration is probably most famous for its extensive policy of municipalisation that earned him the love of workers and the hatred of many industrialists. In 1955, La Pira’s city government took over a failed foundry and turned over its operation to the workers, allowing them to elect their bosses from among their own ranks. In response to changes in national government policy that allowed evictions from rent-controlled apartments, La Pira requisitioned old Fascist buildings and even the villas of wealthy Florentines for the purpose of rehousing evicted tenants.

In perhaps his most famous action as Mayor of Florence, La Pira saved hundreds of jobs at the Pignone industrial plant, which at that time was making cotton-spinning machines for the textile industry. Due to a slump in demand in the textile business, Pignone was being closed down by its private owners. However, the workers refused to leave, sleeping and taking meals in the factory and continuing to work the machines. La Pira joined the workers in attending Mass and worked with the union leadership to find a resolution to the problem of the plant’s closure. Eventually, La Pira was able to convince Enrico Mattei, the head of ENI, Italy’s powerful state-run energy corporation, to take over the factory and place it under public ownership, thus saving more than one thousand jobs.

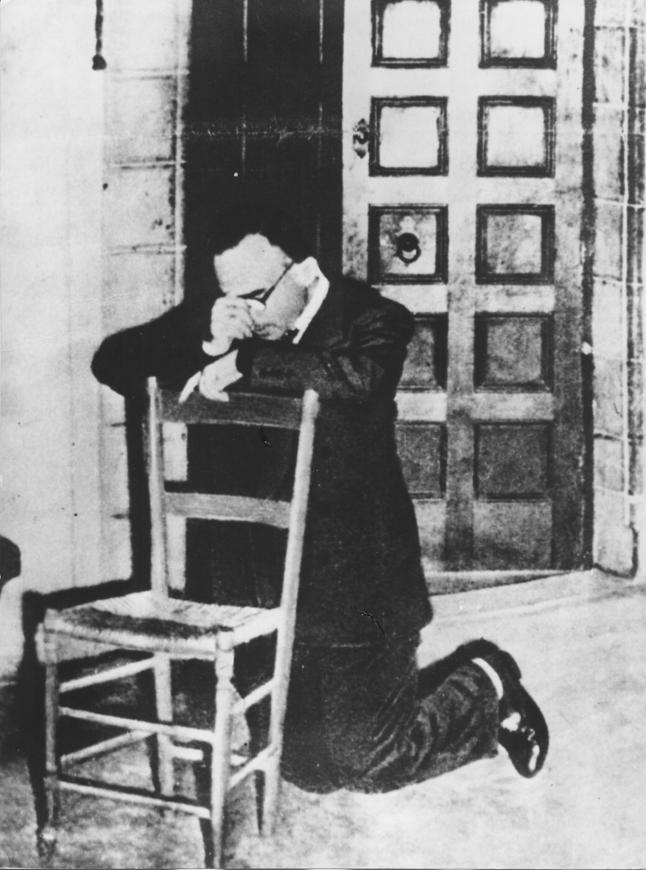

La Pira’s generosity with the public treasury was only matched by his own personal attitude toward those in need. It was not unusual to find the Mayor of Florence walking about with no shoes, no coat, and no umbrella, because he had given away his clothing to the poor. La Pira, who was a Dominican tertiary, lived in an unheated monastery cell in the Basilica of San Marco, although he sometimes lodged with a doctor friend when it was especially cold outside. His behavior caused him to be dubbed “the Saint” by the people of Florence. Indeed, despite the fact that he was hated by many businessmen in Italy, their allies in the Christian Democratic Party could not afford to replace La Pira with another candidate as he was seen as the only person who could defeat the Communists in left-wing Florence.

After La Pira served his final year as Mayor of Florence in 1964, he largely devoted himself to the cause of international peace, working to bring an end to conflicts in Vietnam and the Middle East in particular. His work in favor of disarmament and Third World development also merit mention, and the bespectacled Sicilian even travelled to Chile to try to prevent the coup d’état against President Salvador Allende.

In 1976, Giorgio La Pira returned to active politics at the request of the Christian Democratic Party. Despite ill-health, La Pira stood for election and won a seat in the Chamber of Deputies. La Pira’s last actions as a politician reflect the changing problems of the world he lived in. La Pira was a vehement opponent of abortion and fought against its legalization, with L’Osservatore Romano running his article “Confronting Abortion” on its front page on March 19, 1976. La Pira also spoke out against the increasing violence and materialism of modern society, connecting his opposition to abortion to his support for disarmament and world peace.

On November 05, 1977, Giorgio La Pira passed away. His funeral was unsurprisingly well attended, and the attendees included the thousands of workers whose jobs he saved at the Pignone factory and elsewhere.

Perhaps more than any other member of the Christian Democratic Left, La Pira actively embodied the ideals of a Christian version of social democracy. La Pira put into action his statement that every person was entitled to “a job, a house, and music,” even if it caused many people within his own Christian Democratic Party to accuse him of statism or “spurious Marxism,” as the venerable Don Luigi Sturzo, one of the founders of Italian Christian Democracy, put it.

La Pira responded to Don Sturzo by describing the dire unemployment situation in Florence, particularly among the young, and asking him what he would do if he were mayor. In our own age, when so many people are left out of work, when so many young people cannot start families because the market cannot provide enough work to form the economic basis of family life, Christians cannot shrink in fear from accusations of statism or Marxism. Giorgio La Pira provides us with a bold example of political action in favor of peace, family life, and social justice (including justice for the unborn) with real meaning, not just words.

In Cardinal Benelli’s sermon preached in the Duomo at La Pira’s funeral, he asserted that “everything about La Pira can be understood through faith, without faith nothing about him can be understood”. Nor is there any doubt that this is the sole key to understanding “the Professor’s” life.

His fundamental working hypothesis, expressed in every sort of circumstance and in every place, was always based on the certainty of the resurrection of Christ: “if Christ be risen, as He is risen…” he used to say, going on to affirm that the entire history of all peoples is conditioned by this event.

“The holiness of our century will have this characteristic. It will be a holiness of laypeople. We encounter on the streets those who within 50 years may be on the altars–along the streets, in factories, in parliament and in university classrooms.” -Giorgio La Pira

O God, You have given to Your servant Giorgio La Pira

the grace to testify admirably in the cultural, social and political life of our time.

Grant us the grace, we ask, that the Church may recognize his heroic virtues and is revered by the Christian people as inspirer of charity, justice, peace. Amen.

“There is no doubt that the Lord had placed in my soul the desire for priestly grace; only, however, that He wished that I remain in my lay garb to labor with more fecundity in the secular world far from Him. But the goal of my life is clearly marked out: to be the Lord’s missionary in the world; and this apostolate will be carried out!”

-April 1931 Giorgio La Pira (from the letter to his aunt, Settimia Occhipinti)

“One last thing: I am not a priest, as you have supposed: Jesus did not want that of me! I am just a young man to whom Jesus has given a great grace: the desire to love Him without limits and to have Him be loved without limits.”

-Easter 1933 (16 April) Giorgio La Pira (from the letter to the Mother Prioress of Santa Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi)

“Then the LORD asked Cain, “Where is your brother Abel?” He answered, “I do not know. Am I my brother’s keeper?”

-Gen 4:9

Love,

Matthew